By Charles W. Sasser

On January 30, 1945, a group of U.S. Army Rangers, Alamo Scouts, and Filipino guerrillas set out on a daring nighttime raid on Cabanatuan POW camp in the Philippines. Led by Ranger Colonel Henry Mucci, they hoped to rescue over 500 American prisoners, including some held by the Japanese since the Bataan Death March.

One of the great tragedies of war for the United States in the 20th century has been the suffering of American military servicemen seized by the enemy. During World War II, American GIs held captive by the Japanese confronted starvation, disease, despair, brutality, and death. Behind bars and barbed wire, they waited year after year, looking to the skies and praying for release or rescue. Many died waiting.

Four months after Pearl Harbor, in April 1942, the Imperial Japanese Army invaded the Philippines where it cornered and captured nearly 80,000 defenders near Mariveles on the Bataan Peninsula of Luzon, some 12,000 of whom were American GIs. They were herded to the National Highway for the 65-mile march to Camp O’Donnell that became known as the Bataan Death March. More than 1,000 Americans died or were savagely murdered on the way.

Roughly half the surviving American POWs were transferred to Cabanatuan, a former Philippine Army recruit training camp 40 miles northeast of O’Donnell. Less than three years later, disease, execution, random murder, and shipments to slave labor districts in Formosa, Manchuria, Japan, and other sites had reduced the inmate population to 600 or less.

In October 1944, General Douglas MacArthur kept his promise to the Filipino people: “I shall return.” General Walter Kreuger’s Sixth Army landed with MacArthur at Leyte. Then, on January 9, 1945, Americans went ashore at Lingayen Gulf on the west-central coast of Luzon and began to press toward Manila.

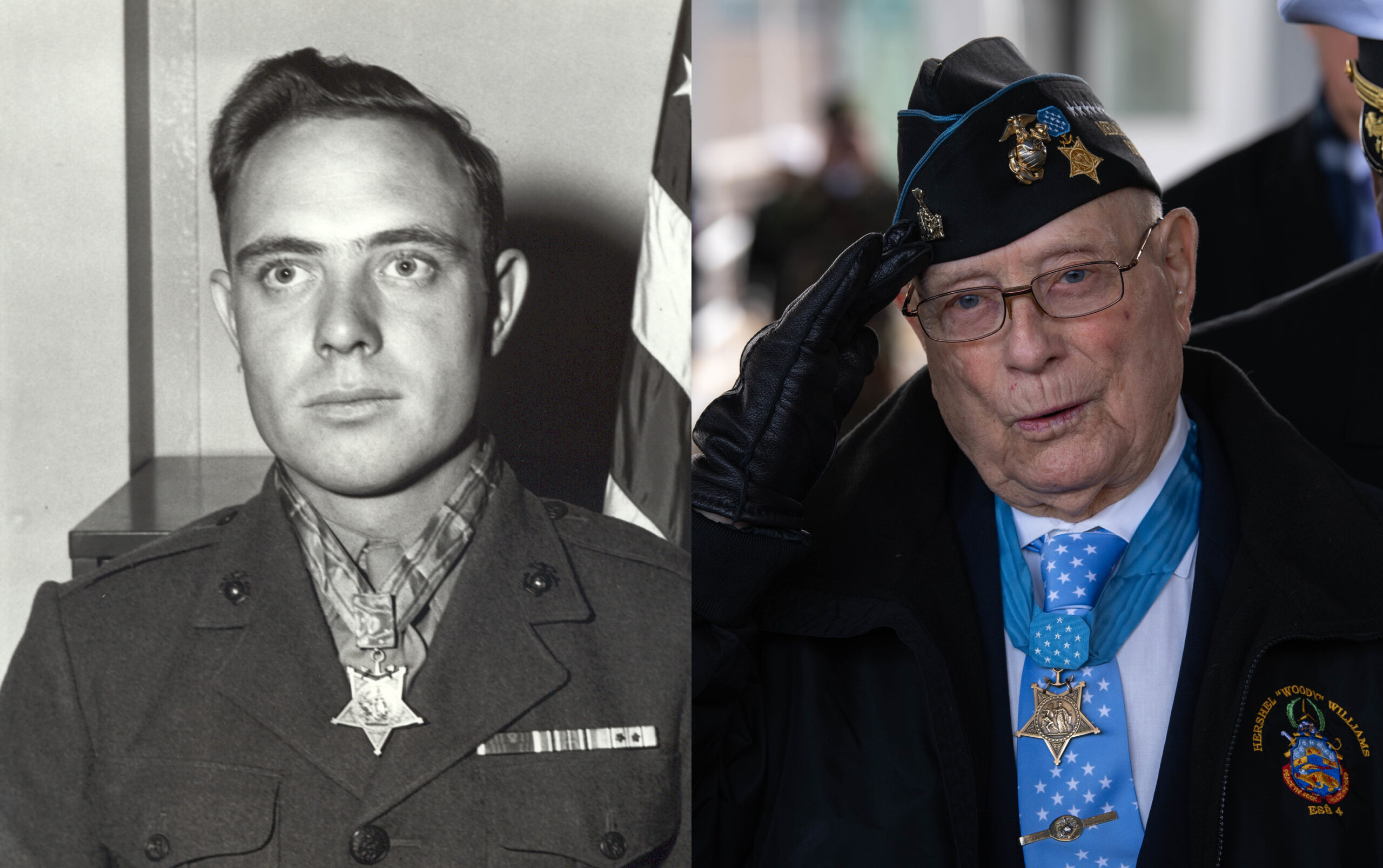

Among MacArthur’s landing detail was a 19-year-old private of the Sixth Army’s Alamo Scouts who had participated in a successful raid to rescue 66 civilians held as slave labor by the Japanese at Cape Oransbari in northwestern New Guinea. Galen Charles “Kit” Kittleson was the eldest of eight barefooted offspring from an Iowa farm. A closed-mouthed diminutive soldier barely five feet four inches on a tall day, he was the youngest fighter assigned to the elite Alamo Scouts.

“The other day I happened to overhear the longest conversation Kit’s ever had,” went a standing joke. “Kit says to Olsen, ‘Let’s go to chow.’ And Olsen says, ‘Okay.’”

At Luzon, Kittleson was nonetheless bold enough to ask the stern-faced supreme commander when, if ever, they were going to rescue the Bataan Death March survivors. MacArthur fixed his hawk’s gaze on the little private.

“Were you on the Cape Oransbari raid, son?” he asked gruffly.

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, son. Let me tell you this. You be ready when the time comes.”

The Sixth Army had been activated for service in the Southwest Pacific on January 22, 1943, under the command of General Kreuger. Fresh out of airborne parachute training, Kittleson arrived in New Guinea as a Sixth Army replacement in November, just in time to volunteer for the Alamo Scout Training Center established to “train selected volunteers in reconnaissance and raider work.” The Scouts retained 117 enlisted men and 21 officers.

Their reputation would far exceed their small number. It would be built upon two missions to free prisoners of war from the Japanese—the Cape Oransbari rescue and, soon, the raid to free the American POWs at Cabanatuan.

On January 26, 1945, as the Sixth Army pushed inward toward Manila from Calasiao, a thin major in a worn uniform and riding a travel-weary bay horse halted at the edge of the encampment to ask a group of GIs directions to headquarters.

“I wonder who that is,” Private Kittleson mused as the traveler continued to the far side of tent city.

“Don’t you know nothing, private?” Willie Wismer joked. “Don’t you recognize the most famous American guerrilla chief in the South Pacific?”

U.S. Major Bob Lapham, who commanded Filipino guerrillas, had urged his spent horse through 30 miles of Japanese-infested terrain to bring crucial information about the Bataan Death March survivors at Cabanatuan.

“Sir,” he reported to General Krueger’s intelligence chief, Colonel Horton White, “there is imminent danger that the prisoners of Cabanatuan will be massacred out of vengeance when our units start approaching the camp. If we wait much longer, we’ll be able to rescue what’s left in one carabao cart.”

Colonel White nodded. “What’s the enemy situation at the camp?”

“The road in front of the prison camp is heavily traveled by tanks and vehicles withdrawing toward the mountains or establishing defensive positions. There are 5,000 Japs in and around the town of Cabanatuan and a strong enemy force bivouacked along the Cabu River less than a mile from the camp. At any given time there may be between 100 and 300 Japs inside the compound.”

Willie Wismer burst into his team’s tent.

“I know where we’re going next,” he blurted out. “You guys remember the Bataan Death March?”

Only about 530 surviving POWs celebrated Christmas 1944 behind the wire at Cabanatuan. That number dwindled daily. The camp’s most prominent feature was its large makeshift graveyard where fresh mounds appeared daily. Over half the remaining men were so feeble they couldn’t walk across the courtyard without help. Almost all suffered from gangrene and an array of tropical diseases. Many were missing limbs.

“If I was in that camp,” Kittleson said, “I’d sure hope somebody’d come get me.”

Lieutenant William Nellist confirmed Wismer’s revelation. His team and Lieutenant Thomas “Stud” Rounsaville’s were to be tasked with an important mission. They, along with Charley Company from the 6th Ranger Battalion and two companies of Major Lapham’s guerrillas, were “going 25 miles inside Jap lines to rescue 500 GIs held at the Cabanatuan POW camp…. Be ready to move out at 1630 hours to our forward position in Guimba.”

Never before had U.S. soldiers been called upon to rescue such a large number of POWs from so deep inside enemy territory.

By 1930 hours that evening, Scouts, Rangers, and guerrillas were assembling at Guimba, a cluster of nipa huts now under U.S. control. Everything beyond was Indian country.

At 2100 hours, 13 Scouts and about 50 of Major Lapham’s partisans set out under a half moon to establish advance surveillance on the prison camp. Kittleson ran point with two Filipino guerrillas for the 24-mile forced march over dry rice fields and prairies of tall Kunai grasses. Any enemy encounter might well compromise the mission.

Nine miles into the march, they approached the National Highway between Manila and Cabanatuan. Running lights glowed like cats’ eyes on Japanese truck convoys and tank units crossing the highway bridge to defensive positions in the mountains. The entire patrol slithered a few at a time underneath the bridge to the other side while tanks clanked overhead.

Traffic was light on the Rizal Road that came next. Raiders crossed it without incident to arrive at daybreak in Balincarin where they joined additional partisans under guerrilla leader Juan Pajota. After a brief rest and bowls of rice and beans, the Scouts saddled up for their initial appraisal of the POW camp while the partisans prepared for their phase of the operation.

The Alamos descended into the lowlands along the Pampanga River. Grasses growing head tall provided excellent cover. They waded the river and crawled to the top of a knoll where they parted the grasses and peered out.

The camp sat in the open about 700 yards away. Kittleson noted guard towers and roofs of thatched palm fronds or tin behind high wire. Even a lizard would have a tough time scurrying unseen across the turnip and sweet potato fields that surrounded the stockade to reach the camp’s front gate.

In the meantime, Colonel Henry Mucci, overall raid commander, led his 6th Ranger component of 121 soldiers out of Guimba not quite 24 hours behind the lead Scout element. He linked up in the predawn of January 29 with Filipino guerrillas under Captain Eduardo Joson to the west of Balincarin. Now numbering more than 200, the combined force proceeded to the staging area at Platero about a half mile to the Scouts’ rear and a mile and a half from the POW stockade. Lieutenants Nellis and Rounsaville hiked back to report the Scouts’ observations to Colonel Mucci.

“A Jap division was moving past all night until it shut down at dawn to hide out from planes during the day,” Nellist informed the colonel. “Our bacon will be out for frying if we collide with those bastards.”

“Could the prisoners have been moved?” Mucci fretted.

“We haven’t been able to get close enough to look inside the camp,” Rounsaville said.

Colonel Mucci arched his back. “We’ll postpone the raid until tomorrow night to let the Jap division clear out. In the meantime, we’ve got to get someone close to the front gate. The gate is key to the entire operation.”

A single nipa hut sat isolated in the field about 200 yards outside the prison gate. Kittleson and the other Scouts kept watch while Lieutenant Nellist and Rifo Vaguilar donned local peasant garb and wide-brimmed straw hats to make their way across the fields, stopping now and then to point and squat as though inspecting crops. The peasants had been cautioned to ignore whatever happened or whoever appeared.

Once concealed inside the hut, Nellist observed that the front gate was about nine feet high and made of saw lumber. Strands of barbed wire surrounded the entire stockade. Buildings were either bamboo with thatched palm roofs or mortar and concrete with corrugated tin roofs. Sentry towers studded strategic locations. Prisoners inside tottered about like emaciated scarecrows on their side of a road that beelined across the compound from front to back. Japanese guards estimated to number between 225 and 250 billeted on the opposite side of the road.

That night in Captain Pajota’s hut in Platero, Mucci finalized operations orders with his element leaders.

“As I see it,” he began, “our main threat after the last of the Jap divisions move on through tonight is posed by the 2,000 Japs barricaded at the Cabu Bridge. They could run over us within 10 minutes after the assault begins.”

“They won’t,” promised grim-faced Captain Pajota.

Two companies of partisans totaling 280 fighters were tasked with providing security and a blocking force while U.S. Rangers and Scouts conducted the raid. Pajota’s men had responsibility for stopping the Japs at the Cabu Creek Bridge while Joson’s guerrillas and a Ranger bazooka team set up a blocking force on the road 800 yards southwest of the camp to catch Japanese elements attempting to break through from Cabanatuan town.

“We need a half hour to shoot our way into the camp and herd out the prisoners,” Colonel Mucci estimated.

While the guerrillas had proved themselves in hit-and-run tactics, could they stand their ground against an organized assault supported by tanks?

“I and Captain Joson promise you a half hour,” Captain Pajota said.

The raid on Cabanatuan would work this way: from the assembly point, guerrillas would proceed to their positions to block off the camp. Scouts and Rangers would crawl across 700 yards of open fields under the cover of darkness to reach the prison main gate before 1930 hours. Lieutenant John Murphy would lead his platoon to the rear gate.

“Lieutenant Murphy initiates the attack by opening fire on the guards at the back gate,” Colonel Mucci directed. “That should provide a momentary distraction to allow us to take out the guards at the main gate and bust through into the compound.”

Lieutenant O’Connell’s Scouts would rampage down the length of the beeline road to engage all resistance; Lieutenant Schmidt’s platoon and Captain Bob Prince’s detachment would round up POWs and get them to the front gate while Murphy, coming through the back gate, covered them; Alamo Scouts and a squad of Rangers at the secured front gate would hustle prisoners to the river where 150 Filipino irregulars waited with carabao carts to make the escape.

Everything had to work precisely for the raid to succeed.

“Remember,” Colonel Mucci cautioned, “these boys have been in that shit hole beaten and starved for nearly three years. If they can’t walk to the river, carry them. We don’t leave one of them behind. Not a single one! We attack tomorrow night. I think the date of 30 January 1945 will be long remembered. Go with God—and bring our boys home. They have not been forgotten.”

An Allied Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter buzzed the camp on the morning of January 30. Otherwise, the compound lay smoldering quietly in the sunlight. Rangers moved up from Platero in the afternoon and hid in the grass on the knoll with the Scouts. Word passed from man to man as the sun at long last dropped from sight. “Get ready to move out.”

It suddenly struck Kittleson: “What if they had been betrayed and the Japs were waiting in ambush?”

He dismissed the thought and cradled his Thompson submachine gun in the crook of his arms as 121 Rangers and 13 Alamo Scouts moved out through the darkness on their bellies like giant reptiles. Overhead, a U.S. Northrop P-61 Black Widow warplane buzzed the camp at treetop level as a planned distraction. Suddenly, the gonging of a bell reverberated out of the prison camp. Kittleson’s heart threatened to vault from his chest. Only later did the raiders learn that a U.S. Navy POW had improvised a ship’s bell to sound the watch at periodic intervals.

After what seemed an eternity, the Scouts and Rangers slipped into the drainage ditch that paralleled the road in front of the stockade. Through the gate slats Kittleson spotted Japanese guards smoking not 20 yards away. Others in their underwear lounged in the open doorways of lighted barracks. Asian music drifted with the breezes. Apparently, the Japanese felt secure here 25 miles behind the front.

Lieutenant John Murphy and his Ranger platoon approached the back gate along a filthy sewage ditch. It was 1920 hours, 10 minutes until H-hour, when they heard a commanding “Halt!” Either the guard in the tower possessed some acute sixth sense or the moon playing through the clouds revealed something suspicious in the night shadows.

The guard shouted back into the camp to summon help. Murphy decided it was close enough to H-hour. The platoon opened up with a murderous crescendo that took care of the guard in the tower and killed several other Japanese lounging on the stoop of a nearby barracks.

At the front gate, Scouts and Rangers took the cue and brought down their assigned targets. Kittleson scrambled out of the roadside ditch with Ranger Sergeant Ted Richardson, whose task was to smash the padlock on the gate to allow troops to surge inside. An enemy soldier lurking in the shadows took a quick shot, his bullet striking Richardson’s .45 pistol and knocking it out of his hand.

Kittleson responded with his Tommy. The Japanese soldier shrieked and died.

Richardson shook his numbed hand and picked up his pistol. It still functioned. He fired into the gate lock, smashing it. Rangers stormed through while Kittleson, Wismer, and the other Scouts took positions to keep the gate secured while they waited to guide rescued POWs to safety.

Enemy mortar shells rained down on Kittleson and the others. He hit the dirt and heard someone shout, “I’m hit!”

Lieutenant Rounsaville.

“I’m with him,” Nellist called out. “Everybody hold where you are.”

He crawled to his friend’s side. “You’re wounded, Stud. Where’re you hit?”

Rounsaville groaned. “In the ass. Bill, I need you to look at my ass.”

“I’ve seen your ass.”

Flying shrapnel struck Sergeant Alfred Alfonso in the gut and ripped open a Ranger’s inner thigh. Litter bearers rushed to the river with the raid’s first casualties.

“Bill?” Rounsaville called out as he was whisked away. “Thanks for caring about

my ass.”

By this time the fight for the Cabu Bridge down the road had begun. The horizon erupted with explosions and flying tracers as some 200 Filipino irregulars took on 2,000 pissed-off Japanese. Could they hold?

Demoralized and caught off guard, few of the 250 Japanese inside the compound managed to rally anything like an effective defense. Lieutenant O’Connell’s men on the interior road were stacking up enemy bodies against the anvil provided by Murphy’s Rangers coming through the back gate. Panicked Japanese scattered like defenseless chickens.

Japanese officers caught in their underwear stared in shock as blackened-faced GIs burst in and stitched them with bullets. Shouting and roaring with adrenaline, Rangers kicked in doors along a hallway and sprayed dorm rooms with lead.

A ragged figure leaped into sight and threw up his arms. “Don’t shoot. I’m an American!”

He had been at the Japanese officer quarters mending a generator.

“Get to the front gate as fast as you can!” a Ranger instructed.

The scarecrow shambled off toward the gate babbling, “God bless you. Thank God you’ve come.”

In another section of the compound, bazooka gunner Sergeant Stewart and his loader spotted two trucks full of Japanese infantrymen speeding toward the main gate in an escape attempt. Stewart’s well-aimed rockets enveloped both trucks in bright flames. Human mini-bonfires screaming in terror and anguish tumbled from the burning vehicles. Ranger gunfire put them out of their misery.

The rescue also caught Allied POWs by surprise. They thought the Japanese were executing everyone. Some attempted to hide or secure weapons for a last-ditch fight. Most, who were too physically weak to resist, pressed themselves against split bamboo floors and waited in mute stupor for the end of their long suffering.

Thinking he might save some of them, POW Merle Musselman ran on weakened legs toward the camp surgical ward that housed 100 patients. To his consternation, he discovered the beds empty. His staggered outside where a huge man in green with a blackened face startled him.

“Get to the front gate!” the invader ordered. “You’re being rescued.”

Inmate Airman George Steiner began crawling in the muck of a latrine drainage toward the fence. A strong hand jerked him to his feet.

“It’s a prison break!” a voice explained in a deep Southern drawl. “We come to get y’all out.”

POW Sergeant Bill Seckinger thought the Japanese were slaughtering the inmates. “Tear the legs off your bunks,” he yelled. “Get anything you can. Some of them are going to die when they come in.”

Although so debilitated he could barely stand, he wasn’t going down without a fight. Then a voice in English rang out. “You’ll be fine. Head for the front gate.”

A POW named Jackson didn’t let the inconvenience of having only one leg slow him down. He reached the front gate on one leg and the stub of the other.

Ranger Corporal Jim Herrick hoisted a naked bag of bones into his arms and trotted toward the gate. The prisoner suddenly gasped and went limp. One hundred yards from freedom, he had died.

Prisoners emerged from the inferno, all hollowed angles and stench, running sores and lost limbs, staggering, hobbling, tattered skeletons, and scarecrows crawling like zombies emerging from graves into unexpected light. Blinking, weeping, laughing, thanking God and their liberators. Dead men returned to life.

The scene brought tears to Private Kittleson’s eyes. He and the other Scouts began carrying and escorting the prisoners to freedom. They waded the muddy Pampanga to where more than two dozen two-wheeled wooden carabao carts waited.

“If they’re too bad off to walk,” came an order, “put ‘em in the carts.”

Kittleson tenderly lowered a naked man onto a grass mattress in one of the carts. The guy, who weighed no more than a child, was sobbing with gratitude.

Colonel Mucci fired flares to signal the raid completed and let Pajota and his men at the Cabu Bridge know to withdraw from a battle they were doomed to lose if they stayed with it long enough. The walking dead and their liberators, a procession nearly a mile long, pulled out in the dark to the sound of sobbing, shuffling feet, and rattling carts. The raid on Cabanatuan was over in 28 minutes. The Japanese garrison was destroyed. The bloodied remains of Japanese soldiers littered the wreckage.

The rattle of bull carts soon faded into the night.

Galen Charles Kittleson retired as Command Sergeant Major of the U.S. Army’s 7th Special Forces Group. During the Vietnam War, he twice more penetrated enemy lines to rescue American POWs. Other than the raid on Cabanatuan, the raid against the Hotel Hilton POW camp only 23 miles from Hanoi in North Vietnam on November 21, 1970, is undoubtedly the most daring and famous in American military history. Kittleson is the only American soldier ever to have participated in four separate POW raids.

Charles Sasser is the author of the classic book of sniper warfare titled One Shot-One Kill. He has written dozens of other books and articles and appeared on numerous television networks including ABC, Fox, the History Channel, and CNN. He is a veteran of the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army Special Forces. He resides in Chouteau, Oklahoma.