By Robert Heege

It was June 24, 1866, late in the afternoon of a northern Italian summer, and Venice, the jewel of the Adriatic, was bleeding again. Down a dusty dirt road on the sun-streaked outskirts of the fabled city, a dejected, rag-tag column of beaten, broken men trudged sullenly on.

Seventy humiliating years of restive occupation under the oppressive yoke of the Habsburg Empire had left its mark on this legion of dazed automatons, as it had upon their fathers and their grandfathers before them. The abortive attempt of this new generation of starry eyed redeemers to rise up as men and cast off the shackles of their despised Germanic overlords had failed, utterly, like all the others before it.

Inspired and emboldened by events swirling all around them, it seemed to a hardy few that the time was right to make common cause with like-minded allies and strike a blow for themselves, but their ad-hoc insurrection quickly came to naught. In the space of a single day, albeit a cruel and bloody one, the fight had been taken right out of them. Their would-be saviors fared no better, and for the second time in 18 years, the age-old dream of a glorious Venetian revival, coupled now with another Risorgimento—a resurgent new vision of a single, unified nation upon the Italian peninsula—had been thoroughly blasted to pieces. The chains, it seemed, would remain.

Defeated, demoralized, and shamed before God and the venerable achievements of their glorious ancestors, some men wept, while others cursed the fates that had denied them, mocked in retreat by the incessant hum of the cicadas and the sight of the great Romanesque domes and spires of the Basilica di San Marco still visible at their backs.

Once the prosperous and glittering center of an unparalleled maritime power, whose merchant galleys and mighty warships had plied the seas for centuries, the legendary Venice of old had been a true thalassocracy, a seaborne empire with territorial acquisitions stretching far beyond the tranquil lagoons of its pocket-sized homeland.

These latter-day lions of Saint Mark were desperate only for water and bread and a bit of shade, possessed by nothing more than an almost feral desire to put as much distance as was humanly possible between themselves and their hated, perennial nemesis, the Austrians, before the shadow of night descended like a black curtain over the blood-soaked soil and shattered hopes of Venetia.

In true Italian style, part tragedy, part rueful comic opera, what was quickly dubbed the Second Battle of Custoza and the events that led up to it were all part of a larger, chaotic, interconnected mosaic, a metronome of human aspirations, political cross-purposes, military adventurism, opportunism, and international skullduggery that became known to history as the Third Italian War of Independence. For captive Venice, after a long, galling series of slights, it was just another slap in the face.

In an age of petty kings and kingdoms, La Serenissima, the Most Serene Republic of Venice, had been the storied realm of the doges. Indeed, few states in history could boast of anything like the illustrious 1,000-year pedigree of Venetia. But by the early 19th century all of that had become the stuff of nostalgia and faded memory.

To begin with, the travails of Venice aside, the very concept of a unified Italian peninsula forged into a single nation state was a relatively new one in 1866. Not since the fall of Rome in the 5th century when the Visigoths clubbed their way into the Pantheon had there been anything of the kind. Nevertheless, it was the death throes of ancient Rome that had led directly to the birth of Venice, where it is said that in an effort to keep their daughters out of the clutches of the Proto-Germanic invaders and preserve their own ethnic identity several clans took refuge in the marshy wetlands abutting the headwaters of the Adriatic.

There, on 118 tiny islands, many of them little more than sandbars and spits of dry land surrounded by the natural defenses of barrier lagoons, the early Venetians set about building small boats to traverse the distances between each landfall and connecting bridges and canals between the islands wherever possible, adapting to a new life in a water world of their own unique creation.

In the generations that followed, their descendants laid the foundations of an expansive trading network in the eastern Mediterranean. Venice grew ever more prosperous and powerful, and over the next several centuries, as her galleys swept the sea lanes and the profits rolled in, tiny Venice became a force to be reckoned with.

Eventually, the coming of Islam and the rise of the Ottoman Turks in the eastern Mediterranean dimmed the sparkling brilliance of Venice’s storied maritime thalassocracy. For a time, her venerable trading network stubbornly endured, buoyed by the strength of her powerful navy and shrewd diplomacy with her European neighbors.

But by the 1700s, Venice, while still the cultural pearl of Europe, had neither the need nor the inclination to maintain its once enormous fleet of galleys. She became more inward looking, content to slumber within the picturesque confines of the lagoons.

That peaceful idyll ended abruptly in the spring of 1796, when a new foe emerged much closer to home. Napoleon Bonaparte, the glory-hungry warlord of revolutionary France, was by then breathing down the necks of the patchwork of weak little kingdoms that had dotted the landscape of the Italian peninsula for hundreds of years. France’s only real rivals in the region were the Austrians, so Bonaparte quickly set about neutralizing them by going on the attack, driving them out of their holdings in Lombardy. In the course of their headlong retreat, the Austrians overran Venetia, pausing only long enough to loot the city of Venice in the face of the advancing French forces, which followed suit and proceeded to sack the city for a second time. Moreover, once there, the French had no intention of leaving, and the Venetians, never a land-based power in Europe, found themselves utterly overwhelmed by the unprovoked onslaught.

Bowing to the little corporal’s demands, the last Doge of Venice abdicated, practically at bayonet point, in May 1797. The no longer serene republic was summarily abolished, and a French military governor began calling the shots. Later, in a cynical deal to make temporary friends of his enemies, Napoleon signed treaties with the Habsburgs that included some advantageous land grabs, all at the expense of the Venetians, who saw their landed territory west of the lagoons (the Veneto) and the city of Venice itself ceded to his Austrian partners in crime.

The eventual defeat of Emperor Napoleon I and his war machine in 1815 did nothing to improve Venetian fortunes. At the postwar Congress of Vienna, the skillful diplomatic maneuverings of Austrian Prince von Metternich and veteran French diplomat Charles Talleyrand dominated the proceedings. As a result, the vanquished got off lightly. The main obsessions of the victors, putting all the sovereigns of Europe who’d been deposed by Napoleon back on their respective thrones, restoring the French monarchy, and restoring all the original antebellum borders were all achieved—with one glaring exception: the city of Venice, indeed, all of Venetia, was to be merged with Austrian-controlled Lombardy.

For 33 years, Venice simmered under the Austrian boot. Then, in 1848, a wave of political unrest that began in Austrian-controlled Hungary sent seismic shockwaves crackling throughout Europe. In France, the pear-shaped King Louis Philippe was sent packing. But the Austrian emperor had better luck than his corpulent Gallic counterpart. The revolt in Hungary was brutally suppressed, as was a full-blown popular revolt in Venice that it had inspired, known today as the First Italian War of Independence. But, as its name suggests, it would not be the last.

Ten years passed. Giuseppe Garibaldi, a hero of the uprisings of 1848, had fled into exile like so many others, but by 1854 this international man of the people had returned and was re-directing his dynamic energies toward a new ideal, that of a Risorgimento or resurgence, a restoration of ethnic pride and shared national identity. His followers, the Red Shirts, named for the blood red shirts they wore, believed that by banding together as one people, regardless of regional differences, they could at last expel the foreign powers that had long plagued the peninsula and bring together the disparate, squabbling collection of regions and rump states into a single, strong, reunited nation.

In 1859, Garibaldi’s fellow travelers in the nascent Pan Italian movement suddenly found themselves in the cossetted embrace of a most unlikely ally. The big winner of the revolutions of 1848 had been one Charles-Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, the nephew of the great Napoleon. In 1852, with the blessing of the French people, he assumed the Imperial title.

By 1859 Emperor Napoleon III, as he fashioned himself, was cheerfully indulging his penchant for opportunism, intrigue, and political mischief in support of the Risorgimento by dispatching his resplendently attired troops into northern Italy to entice, encourage, and otherwise assist his newest protégé, the 39-year-old king of Sardinia-Piedmont, Vittorio Emanuele II.

Despite his own father’s dismal performance as a freedom fighter with a pedigree in 1848, Vittorio Emanuele II was seen by a great many as the natural candidate to take up the banner of the Risorgimento, including, most crucially to his prospects, the charismatic Garibaldi. It was little wonder then, that the vainglorious Napoleon III was keen to pull the king of Sardinia-Piedmont into his sphere of influence by engineering a joint effort to squeeze the Habsburgs out of their holdings in Lombardy and Venetia, and by so doing, undermine his Continental rival, the emperor of Austria.

Thus, on June 4, 1859, near the northern Lombard town of Magenta, a mighty host of 50,000 Frenchmen joined by a Lilliputian force of 1,100 Piedmontese forded the Ticino River from Piedmont, led by their respective monarchs, and crossed over into Lombardy-Venetia seeking battle. The French-led Second Italian War of Independence was on.

Slamming headlong into the Austrian right, the attackers forced their quarry into a fighting retreat across the cramped, uneven terrain until they came upon a landscape of country orchards riven by a network of irrigation ditches. There, the Austrians made their stand, fighting tooth and nail to heed their officers’ orders to either hold their positions or die trying. In reply, the obliging French spent the day blasting away at them with abandon, until the little streams that burbled through the area took on a sickening pinkish-purple red hue— a color that has been known as magenta ever since—as Austrian blood found its way into the water that fed the orchards. Three weeks later, about six miles from the shores of Lake Garda, at a benighted spot on the map called Solferino, a name that has since become a byword for slaughter, a similarly lamentable scene unfolded.

His battle laurels tarnished by unflattering press reports, Napoleon III quickly tired of his Italian sojourn and began sending out feelers to his imperial cousin, Franz Josef of Austria, stipulating the surrender of nearly all of Lombardy to France as the price of peace. Venetia, though, would remain firmly bound to the Habsburg Empire. The Austrians, still reeling from the horrific and humiliating mauling they had sustained at Magenta and Solferino, all but leapt at the idea, and a treaty was concluded with an almost unseemly haste just over the Alps in Zurich, Switzerland.

Vittorio Emanuele was mortified, but his mood improved considerably when the devious French emperor promptly ceded his newly acquired Lombard province to his Savoyard ally. Napoleon III cynically declared a victory for peace and returned home. But Vittorio Emanuele II was a man of conviction. He had other ideas about what a real victory would look like, and so, too, did lifelong revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi, who had long regarded Vittorio Emanuele as the very model of an enlightened, liberal monarch. Receiving Garibaldi’s blessing was akin to a coronation. Bowing to the prevailing winds of change, one by one the other royal and assorted blue bloods offered obeisance to the scion of the House of Savoy, Vittorio Emanuele II, who was now snapping up provinces on the Italian peninsula one by one, even managing to acquire most of the territory of the Papal States.

On October 26, 1860, Garibaldi and the man he had virtually anointed met face to face. It was then that Garibaldi, the white-bearded old warrior, addressed Vittorio Emanuele as the king of all Italy from the Alps to Sicily. Doffing his famous rounded cap, he handed the younger Savoyard an Italy that was united for the first time in nearly 14 centuries.

On March 17, 1861, Vittorio Emanuele II was duly crowned as the king of Italy. Apart from the old Roman capital, only Venetia remained unredeemed. Acquiring Venetia became the new nation’s burning obsession.

At that same time, Prussian statesman Otto von Bismarck was trying to corral the various independent German kingdoms into a single German empire, with his master, the king of Prussia at its head. Reading the tea leaves, many of the lesser states looked more and more toward their perceived big brother, Austria, as the natural protector and guarantor of their independence.

Bismarck decided to put an end to this ongoing Austrian involvement in the political affairs of the lesser German states and scotch their mutual efforts to stymie his grand scheme. A short, sharp war against an unprepared, reluctant adversary would be just the ticket, and so on June 14, 1866, Emperor Franz Josef of Austria found himself maneuvered into a war with Prussia.

Secret negotiations between Prussia and Italy had been initiated, with arch-intriguer Napoleon III of France volunteering his services as a go-between. Thoroughly seduced, the Italians agreed to attack the Austrians in Venetia while the Prussians were simultaneously mounting their main event in an entirely separate northern action that would drive a wedge deep into Habsburg territory in the province of Bohemia, thus inflicting a psychological blow by threatening the cohesion of Austria’s sprawling, centuries old, painstakingly acquired empire.

The Italian offensive was a sideshow designed to compel the Austrians to siphon off badly needed troops that they would otherwise be sending into the line against Prussia’s legions. The Italians were perfectly willing to swallow this bitter pill as long as the price of their equanimity would be the whole of Venetia and the reclamation of Venice.

The Italian army was still struggling to integrate the armed forces of the formerly separate states that now constituted the singular Kingdom of Italy into one effective force. Despite personal appeals from the king, the Italian officer corps remained a hotbed of bitter jealousies and unresolved personal feuds. In short, the newly minted Italian army was poorly trained, poorly equipped, and exceedingly poorly led.

Like clockwork, the Prussians sprang into action on June 14. They initially concentrated on soft targets, such as Hanover, Saxony, and Bavaria, peeling them away from their paternal Austrian ally. Next, they turned their considerable energies toward their main objective, that of isolating and panicking the lumbering Habsburg elephant, before driving it into the reeds and circling in for the kill.

The Italians, after an abundance of caution, declared war on their despised Austrian enemy on the June 19, 1866; however, they were so disorganized in their mobilization that they could not manage to field so much as a single platoon until June 23.

When they finally did so, they invited disaster from the very outset of the campaign by adopting a war plan that would divide their forces in two before they had even fired a single shot in anger. This marked the quixotic start of the Third Italian War of Independence.

As dawn broke on the morning of June 23, 11 infantry divisions supported by an additional division of mounted cavalry, 120,000 men in all, set out across the Lombardian plains in a line of advance so ponderous and slow moving that nearly 55,000 of them were still bringing up the rear when the main body forded the River Mincio and made its way toward Austrian-controlled Venetia. Christened the Army of the Mincio, it was under the command of General Alfonso Ferrero la Marmora, a 62-year-old nobleman and veteran of the Crimean War. Marmora, who sported an impressive tapered moustache and long, pointed goatee, bore a striking resemblance to Napoleon III, a fact that was not lost on either man when they had met with Bismarck to negotiate their secret accord.

La Marmora had set aside his royal appointment as the first premier of the infant kingdom for a chance to march to the sound of the guns one last time. Tagging along in this search for glory were the king himself and his two sons, Crown Prince Umberto and his younger brother Prince Amadeo.

La Marmora was initially tasked with launching an attack against the dreaded Quadrilatero, Austria’s strategic quadrilateral fortress system. Meanwhile, a second force of another eight full divisions was making its way through the wheat fields just south of the River Po to engage the Austrians on the outskirts of Mantua, on the far end of their formidable defensive system. The Army of the Po was commanded by yet another elaborately bewhiskered, well-connected nobleman, General Enrico Cialdini, the Duke of Gaeta. The abrasive Cialdini was well known for his frequent fits of pique within Italian military circles. Moreover, it was equally well known that he and la Marmora, the two most senior officers in the Italian army, cordially detested each other.

La Marmora reached the first of his objectives, the quadrilateral strongholds at Peschiera del Garda, and Mantua and, according to plan, prepared his attack.

Standing resolutely against the general’s numerically superior force was the main body of Austria’s somewhat less romantically monikered South Army, consisting of three army corps, a reserve division, and one division of cavalry, a total of 75,000 men. What it lacked in numbers, though, the South Army more than made up for in glittering imperial titles, as its upper ranks were chock full of barons. The field marshal’s baton of overall command was clenched firmly in the gloved hand of Austrian Archduke Albrecht von Habsburg, the emperor’s cousin.

The Austrians received excellent intelligence regarding the Italian incursion before they had even reached the Mincio. Archduke Albrecht was canny enough to make the correct command decision early on to concentrate the bulk of his forces in a strategic defense within the vicinity of the fortresses in order to blunt the spear of la Marmora’s obvious intention, a thrust into Venetia, while simultaneously deploying a token force to check any potential movements on the part of Cialdini and his Army of the Po, operating at what was fast becoming the extreme edge of the offensive perimeter, a development that was apparently lost upon the egotistical martinet, Cialdini.

Cialdini was convinced that the approaching Austrians he was observing were the main event about to break open all around him and braced for the onslaught. Unable to dissuade him, la Marmora, who would find himself fending off a major Austrian counterattack by day’s end, inexplicably left Cialdini to his own inert devices and proceeded on with his mission. Thus, the chain of command, like the lines of communication between the two, were effectively severed early on.

About the only thing that would go according to plan that day was la Marmora’s successful effort to convince the king to proceed north with a small force that would place him conveniently and safely out of the way, so far afield from the central theater of operations that he was literally within sight of the Alps.

With the king obligingly en route to his Alpine idyll, la Marmora left almost two full divisions and all of his reserve artillery behind in an attempt to bottle up the Austrian forts, and with his remaining force of 50,000 men, proceeded with his advance into Venetia. At the same time, Albrecht was already directing elements of his South Army to move westward from their positions near Verona on the Adige River to head them off. Racing due west, he resolved to catch the Italians well to the south of him, mount a surprise attack from the rear, and cut them to pieces in one fell swoop.

By early the following morning, June 24, with the momentum of his unwieldy advance already showing signs of bogging down, la Marmora, sensing that a major engagement with the enemy was imminent, made a course correction in a frantic search for higher ground. The logic behind his decision was sound enough, but his timing could not have been more deplorable.

Coming within sight of the hilltops just outside the picturesque Veronese town of Villafranca, la Marmora impetuously directed his men to immediately take the high ground without performing so much as a routine cavalry reconnaissance. Gamboling headlong toward the hilltops, where the lush vegetation was studded with half a dozen tiny villages and sleepy little hamlets, Oliosi, San Rocco, San Giorgio, and Custoza among them, the Army of the Mincio ran straight into the teeth of the South Army, which was already in the process of securing the position and girding itself for battle.

Having lost his early numerical advantage by splitting his command again and again, neglecting to maintain a disciplined line of march during the advance into Venetia, and failing even to establish, much less secure, adequate lines of communication between himself, his field commanders, and his increasingly thinly spread forces, the battle that erupted on the hilltops outside Villafranca quickly devolved into utter chaos for the would-be Italian conquerors.

As the smoke of spent gunpowder clouded the air in the hills above Villafranca, even the methodical Austrian commander Archduke Albrecht, who was observing the action at a distance through his field telescope, could not be entirely sure of what was happening. But la Marmora, who some distance away was squinting frantically into the northern Italian sunlight with barely a scrap of intelligence, had left himself virtually blind. Operating with little to no information regarding the disposition of the enemy—or of his own troops—he sat in his field tent in a state akin to mental paralysis.

At that point, there was a complete breakdown of command and of loss of unit cohesion within the Italian ranks. Confusion reigned. Then, at about 7 ama wing of the 13th Austrian Regiment of Uhlans under the command of General Ludwig von Pulz entered the fray. Unable to restrain themselves, they mounted their chargers without waiting for proper orders from von Pulz and charged toward Villafranca, training their lances on the unfortunate troops of a division of the Italian III Corps under the battlefield command of General Giuseppe Govone.

The appearance of the dreaded Uhlans coming on like a horde of bloodthirsty mounted devils gave rise to a general disorder in the ranks of III Corps and the complete loss of nerve on the part of its overall commander, General Enrico Della Rocca. A multi-titled nobleman, staff officer, and close adviser to the king, Della Rocca, despite a chest full of medals, had not held an actual battlefield command in years.

Della Rocca’s total loss of backbone at this pivotal moment kept his other divisions at a near standstill. Meanwhile, whole groups of Govone’s men were being ridden down like dogs in the olive gardens of Villafranca, lanced front and back in their desperate attempts to escape impalement. Not even the exhortations Crown Prince Umberto, who was on hand to witness the debacle and who had known Della Rocca since he was a small child, could move him to action. Clinging to orders received earlier from the now incommunicado la Marmora, Della Rocca, much like the ossified Cialdini, held his defensive positions and did nothing. The crown prince openly wept.

This is not to say that the individual Italian soldier was not brave. There were many individual infantrymen who gave their all that day, especially in that hellish, desperate hour. Whether it was a single soldier standing his ground or small bands of brothers gathered together in instinctive defensive clusters all around the small groves and hamlets on the heights above Villafranca, isolated pockets of stubborn, dogged resistance fought like demons, often with neither officers nor orders, refusing to give in to the inevitable.

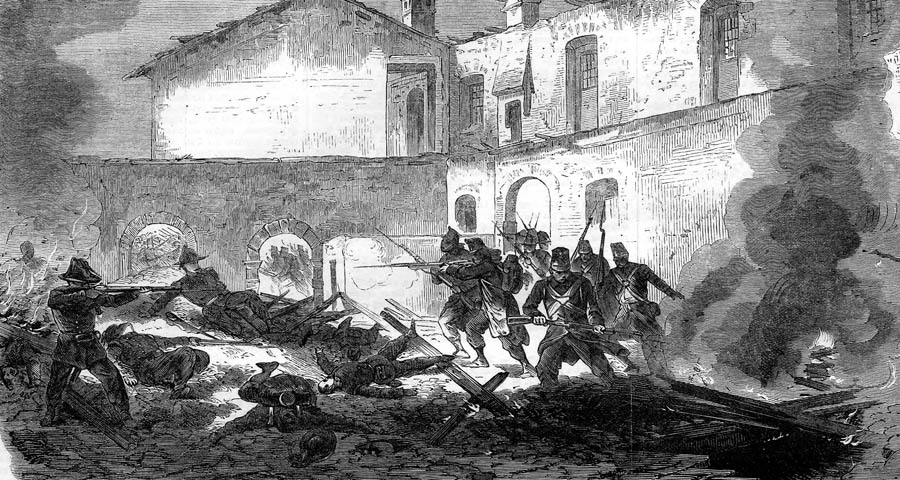

Fierce pitched battles raged throughout that one bloody day, often descending into frenzied melee and spilling over into the tiny hamlets of San Rocco, San Giorgio, Oliosi, and Custoza, as elements of Italian General Giacomo Durando’s I Corps served notice on Serbian General Gabriel Freiherr von Rodic and the crack riflemen of his Moering and Piret Brigades that their Austrian masters had worn out their welcome in Italy as far as they were concerned.

But Rodic and his hard-bitten warriors were there to see that the Italians would not carry the day. In what amounted to an orgy of wanton, mutual butchery in the small village of Oliosi, the Italians finally reached the limits of their endurance and gave ground. In a sudden groundswell of sheer bedlam, the shattered remnants of an entire infantry division broke ranks and fled in a mad dash of humanity that did not stop until they were halfway back to the River Mincio.

Shortly after 8 am another Italian division under the command of General Giuseppe Sirtori attempted to hit back at Rodic and his hard cases, but after enduring withering fusillades of gunfire and several murderous bayonet charges, Sirtori’s men were at last sent reeling back on their heels in retreat.

Nevertheless, a great many of the sons of a united Italy somehow withstood the whirlwind of chaos spinning all around them, and as the bloody fight ground on, the stubborn Italian soldiers managed to punch a few holes in the lines of their equally exhausted Austrian enemies. The diehard, fatalistic heroism that ensued has been enshrined in Italian memory as the Second Battle of Custoza.

An hour later, the Brignone Division, one of the four divisions of Durando’s I Corps, faced off like angry wildcats against Austria’s finest, the IX Corps of the Junker General Ernst, Ritter von Hartung for possession of an otherwise nondescript outcrop beside the little hamlet of Custoza, known as Belvedere Hill, and drove them off with bullets, rifle butts, clenched fists, and even the heels of their boots, sending them scrambling back down the slopes of Monte Croce after another vicious, hour-long infantry slugfest.

But the aristocratic von Hartung, stung by the ignominy of seeing his proud fellow Austrians bested by an army of illiterate peasants, ordered his men to regroup and charge back up into the heights in a deadly game of king-of-the-hill. With la Marmora still frozen in inaction, Prince Amadeo organized a hasty relief party and made for Belvedere Hill, but Austrian marksmen spotted them as they attempted to scramble to the top and opened fire. The attempted rescue was quickly repulsed. The prince, who was badly wounded in the action, was carried from the field. Durando’s fighters were compelled to quit the hill shortly thereafter.

The sight of a profusely bleeding Prince Amadeo being ministered to by his surgeon was enough to temporarily shake la Marmora from his torpor. Suddenly, he was imploring General Govone to send no less than two divisions scrambling up the hillsides to aid the now faltering Brignone Division as its soldiers dug in among the peasant huts and pig sties of Custoza, attempting to fend off the Bock Brigade of Hartung’s IX Corps and the Scudier Brigade, part of the Austrian VII Corps, commanded by Hungarian General Joseph Freiherr von Maroicic.

Govone immediately complied and at length, against all odds, the counterattack began to bear fruit. Both the Scudier and the Bock Brigades were pushed clear out of Custoza. The Scudier Brigade was so badly mauled in the ensuing melee that it was compelled to quit the battlefield. This resulted in a serious breach in the Austrian line that was ripe for exploitation.

Almost on cue, an Italian general, Giuseppe Pianell, who had been sitting on the far side of the Mincio with his troops where he was waiting for further orders that never arrived, made up his mind to act upon his own initiative and seek out the enemy. Crossing the river and linking up with reserve elements of Durando’s I Corps and the battered remnants of Sirtori’s division, Pianell’s ad-hoc command successfully reinforced the left flank of the Italian forces at a pivotal moment in the fight.

Unfortunately, the significance of this development was utterly lost on la Marmora, who had already decided that all was lost just when the enemy was reaching the conclusion that their exhausted soldiers would be unable to go on much longer. After a few nervous glances at his pocket watch, la Marmora, convinced that the game was now up and anxious to get back across the Mincio before his bridgeheads crumbled and he found himself cut off on the wrong side of the river, ordered a general retreat. He was unaware that the redoubtable General Govone’s division had just retaken Belvedere Hill.

Stupefied by the failure of his Italian counterparts to seize the day, an incredulous General Rodic, his Serbian blood boiling, launched an immediate, concerted attack on General Giuseppe Sirtori’s positions. Buckling under the ferocity of the attack, Sirtori’s already bloodied division fell back at 2 pm, creating a huge breach in the line of battle that Rodic’s men proceeded to pour through and exploit with a vengeance.

As a direct result, General Govone, having only just recaptured Belvedere Hill at great cost, found himself almost completely cut off in Custoza, caught between a full Austrian brigade blocking a tenuous escape route over a dilapidated footbridge on the one hand and a vengeful Rodic and Maroicic, the latter acting without orders, gleefully pressing in for the kill on the other.

Wasting no time, Archduke Albrecht ordered von Hartung’s corps to summon up its last ounce of valor and immediately renew the attack on the now thoroughly demoralized Italian divisions, who, abandoned by their superiors, were now abandoning the field, falling back in complete disarray.

Still, up on the hillside, in the shattered, blood-soaked hamlet of Custoza, what was left of Govone’s command, surrounded by the enemy in this, their final redoubt, held out for nearly three more hours as heartless Austrian artillery pounded the peasant hovels and pig sties into powder. At that point, Maroicic, who had been steamrolling his way through like a juggernaut, secured his prize. He mopped up the surviving defenders and began bagging his prisoners.

The Second Battle of Custoza cost nearly 2,000 lives outright and left almost another 7,000 wounded men from both sides writhing in agony on the battlefield, a not insignificant set of numbers considering the small space of time in which it occurred and the compressed nature of the terrain upon which it was fought. By late afternoon it was all over. For all the slowness of their initial advance into Venetia, the Italians could not get back across the Mincio fast enough. As the Austrians would later admit, Austria’s victory had been won for them that day by Italy’s high command.

But victory in Venetia was not victory elsewhere. The campaign against the Italians was all the Prussians had hoped it would be. In the verdant hills of Bohemia at Sadowa on July 3, the Austrian Empire suffered through a Custoza-like disaster of its own.

The Prussians proceeded according to their well-laid battle plan. With a singularly ruthless efficiency, they realized their goal of encircling a bewildered, demoralized Austrian army. In the manner of a pride of lions pursuing a lumbering and confused elephant, they inflicted a crushing defeat upon their suddenly hapless Austrian archrival, delivering a knockout blow so shattering that the Austrians’ will to continue fighting the war was completely destroyed.

Soon after Sadowa, the traumatized Austrians decided to cut their losses and get out while the going was still good. An armistice was brokered within a month, assisted once again by the vulpine French emperor. Eight weeks later, the Austrians officially sued for peace. The Peace of Prague brought about the Habsburg Empire’s permanent resignation from the German Confederation. In the future, Austria would no longer interfere in Berlin’s efforts to corral the lesser German states into a unified German Reich. Austria also would have to surrender Venetia.

Napoleon III was on hand for that treaty ratification, picking up some key territories for France. The Austrians, although they had lost the war and were compelled to relinquish Venetia, pressed the galling assertion that, since the Italian high command had presided over a military debacle of the first order, they did not deserve to be rewarded with the prize of Venice and Venetia. Though Vittorio Emanuele had allied himself with the Prussians, they washed their hands of him. As part of the treaty, the whole of Venetia and the prized jewel of the city of Venice went not to Italy, but to France.

Soon afterward, the wily Napoleon III, who was understandably cautious about adding so restive a province to his own peaceful preserves, and who no doubt relished the opportunity to further humiliate his Austrian rivals, could not resist twisting the knife in one more time. In a self-servingly grand gesture of magnanimity, he announced his desire to cede the whole of the territory to Italy. Not wanting to look like a pauper accepting charity from a rich man, Vittorio Emanuele insisted on putting the issue to a vote.

A plebiscite was orchestrated with the predictable result that the people of Venetia voted overwhelmingly to become a part of the new Kingdom of Italy. The foiled insurrectionists of Venice, forced to flee their beloved city, returned from their short-lived exile to a Venice that was now a part of a united Italy. Within four short years, the French garrison of Rome was recalled. After 15 centuries, Italy was whole and free, an eternal testament to the bravery and sacrifice of the ordinary foot soldiers who had made it possible, the men who paid for it with their blood, the true heroes of Second Custoza.