The horsemen charged into the town from the northeast guns blazing and screaming the hair-raising Rebel yell. Yankees wearing their sleepwear struggled to get out of their tents in the dawn attack and then ran for their lives.

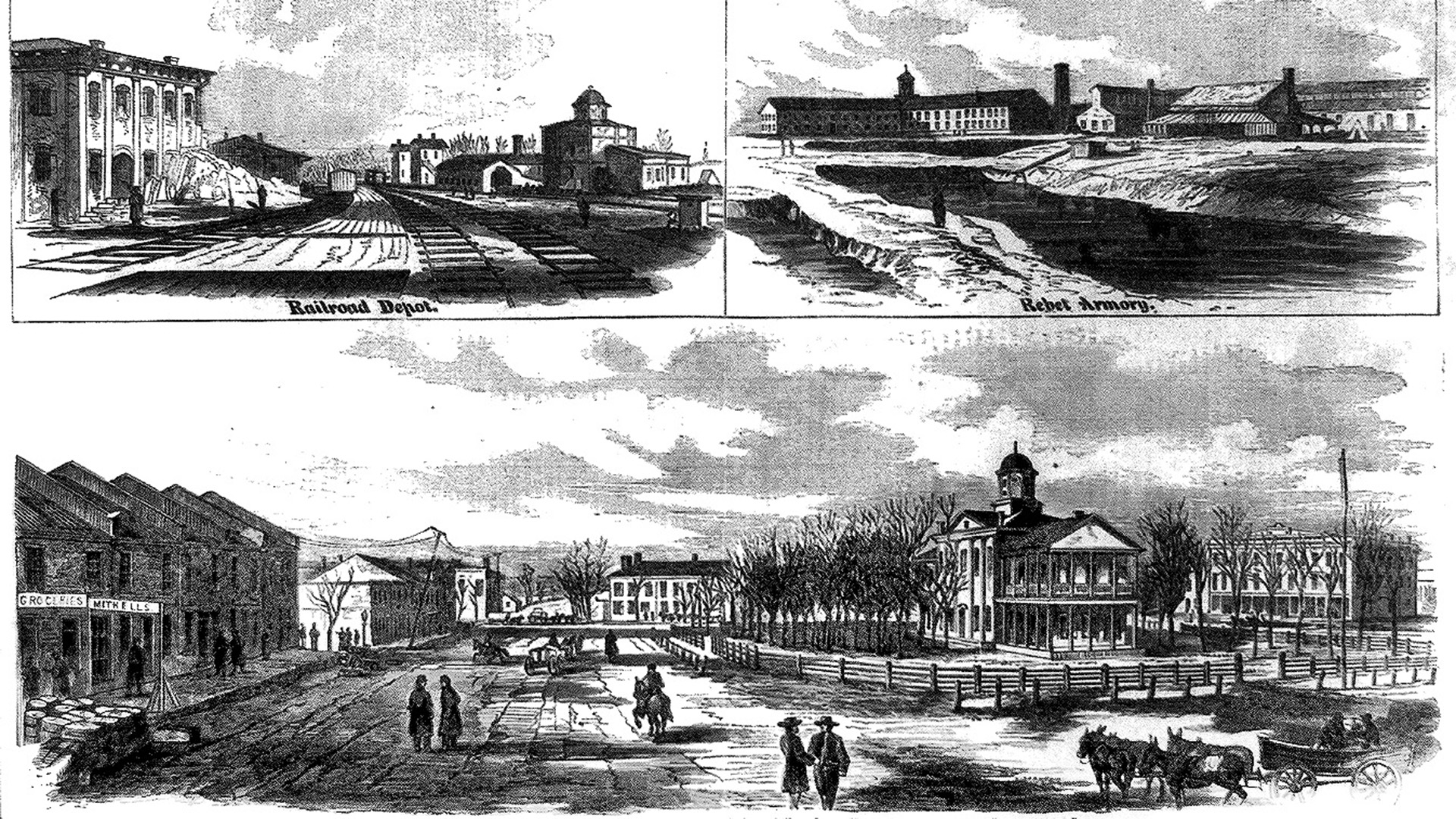

The railroad depot of Holly Springs, Mississippi, was under attack on December 20, 1862.

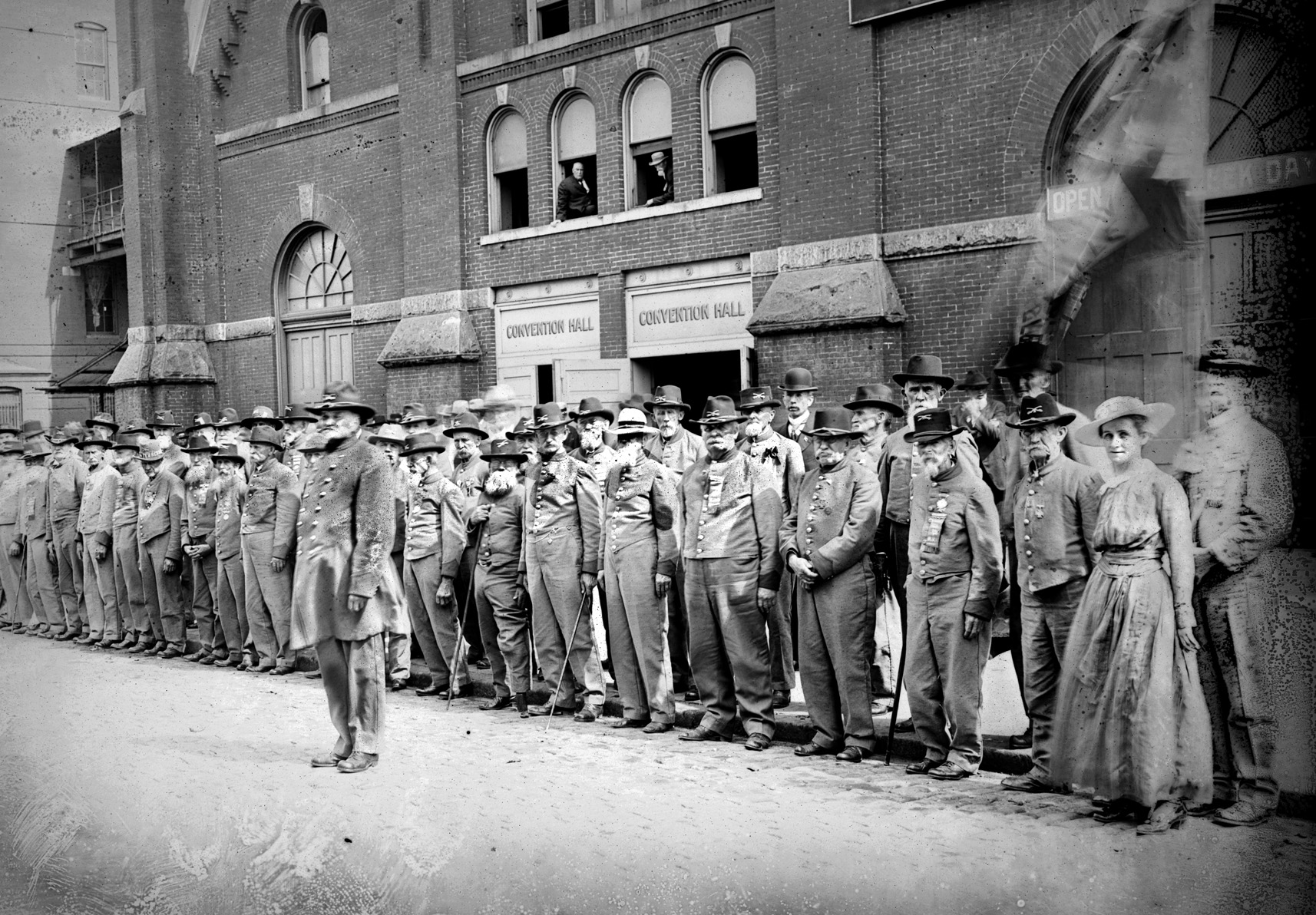

Confederate Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn had three cavalry brigades totaling 3,500 men for the raid. Colonel Robert C. Murphy, commanding 1,500 Illinois cavalry and infantry deployed in three locations around the town, had failed to put his troops on alert even though had advance warning.

“We struck the camp like a thunderbolt,” wrote Colonel A.F. Brown. “The sleeping Federals were partially aroused by the wild cheer given General Van Dorn [by his men], but before the echoes ceased to reverberate, we had literally ridden over them.”

The catalyst for the raid was Lt. Gen. John Pemberton’s desire to disrupt the advance of Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee as it pushed toward Vicksburg. Van Dorn had failed miserably as an army commander in 1862. Pemberton, who replaced Van Dorn, retained him to lead his cavalry.

As a prewar member of the U.S. Army’s regular cavalry, Van Dorn relished a chance to apply his aptitude for cavalry operations. Van Dorn was to suppress the enemy guarding the depot, carry off as much war matérial as possible, and burn the rest.

Van Dorn assembled his raiders at Granada, Mississippi. Grant’s army was bivouacked at Oxford blocking the most direct path. On December 16, Van Dorn led his horse soldiers east and then north.

Locals informed Murphy the night of December 19-20 that a Rebel cavalry column was approaching the town. The Union colonel wired Grant, probably hoping for reinforcements. Murphy’s troops did not put any of his three groups of soldiers on alert. One group of Prairie State infantry was encamped at the railroad station and another in the town. The Union cavalry was bivouacked at the fairgrounds.

The cavalrymen were the only ones who put up a fight. They formed a hollow square and drew their sabers. Van Dorn ordered an attack from various directions. When the rebels broke through one side of the square, 150 Union horsemen managed to escape by riding out of town. Confederate troopers, who had endured 18 months of hardship and rationing, were astounded at the amount of war matérial in the town. Almost every building was packed to the roof with supplies.

Van Dorn and his officers supervised the removal of arms, ammunition, medicine, clothing, blankets, and horse equipment. They then proceeded to torch the warehouses, machine shops, and sutler shacks. The troopers rode off as thick black clouds roiled into the already overcast sky. Grant dispatched several columns of troops to intercept Van Dorn before he could reach the safety of Confederate lines, but none succeeded.

Brigadier General Nathan Bedford Forrest conducted a concurrent raid through West Tennessee against the Mobile & Ohio Railroad. Realizing his long supply line was highly vulnerable, Grant retreated to the Mississippi-Tennessee border for the rest of the winter.

When he transferred to Middle Tennessee in February 1863, Van Dorn committed adultery with a married woman living in Spring Hill. Her husband stormed into his headquarters and gunned him down at his desk. In less than six months, Van Dorn had gone from hero to villain.

—William E. Welsh

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments