By Christopher Miskimon

Lieutenant Colonel Ben Vandervoort’s 2nd Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (2/505) was fighting its way through the Dutch town of Nijmegen on September 19, 1944. As he observed, two of his rifle companies worked their way up a pair of city blocks, supported by British tanks that eagerly zipped down alleys and side streets to assist their American allies with cannon and machine-gun fire.

The goal was to fight through to the town’s bridges. The infantry pressed forward, ignoring their flanks. If the enemy appeared there, they sent a tank back to deal with them. Vandervoort’s men took the high ground, moving to the upper floors of the local houses and advancing rooftop to rooftop. He recalled it as chaos.

“Nijmegen wasn’t all that neat and tidy,” Vandervoort remembered. “In the labyrinth of houses and brick-walled gardens, the fighting deteriorated into confusing, face-to-face, kill-or-be-killed showdowns between small momentarily isolated groups and individuals. Friend and foe mixed in deadly proximity. Germans would appear where you least expected them. You fired fast and straight or you were dead.”

As conceived, Operation Market Garden was simple and bold. A series of airborne landings would pave the way for an armored thrust straight through German lines and across the Lower Rhine River in Holland, opening the way for the Allies to strike deep into the heart of the Third Reich. Success could bring the war to a faster conclusion by outflanking the prepared defenses of the Siegfried Line. The plan required seizing a series of bridges, the last one over the Rhine at Arnhem. The first part of the plan, Market, was the airborne landings using three divisions. The paratroopers would seize bridges and vital terrain and hold them until the ground forces, code named Garden, advanced through their positions and to Arnhem. The ground forces were spearheaded by the British XXX Corps, heavy in tanks and mechanized firepower. The plan was not universally liked by the Allied Powers; their logistical system was strained, and this plan gave supply priority to the British over the American armies to the south. However, if it worked there was a real chance to shorten the war, so the Allied supreme commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower approved the plan despite the risk.

In the event, that risk did not pay off. The three airborne divisions landed with the American 101st closest to the front, the American 82nd in the middle, and the British 1st Airborne farthest into the German lines nearest the Rhine and Arnhem. Unfortunately, Allied intelligence failed to detect a pair of German SS panzer divisions recently transferred to the area for reconstitution. Heavy, desperate fighting ensued, and ultimately the Arnhem Bridge did indeed prove to be “a bridge too far.” However, the final bridges the Allied advance reached, those over the Waal River at the Dutch town of Nijmegen, were the focus of intense combat and courageous acts of bravery by paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne and soldiers of XXX Corps.

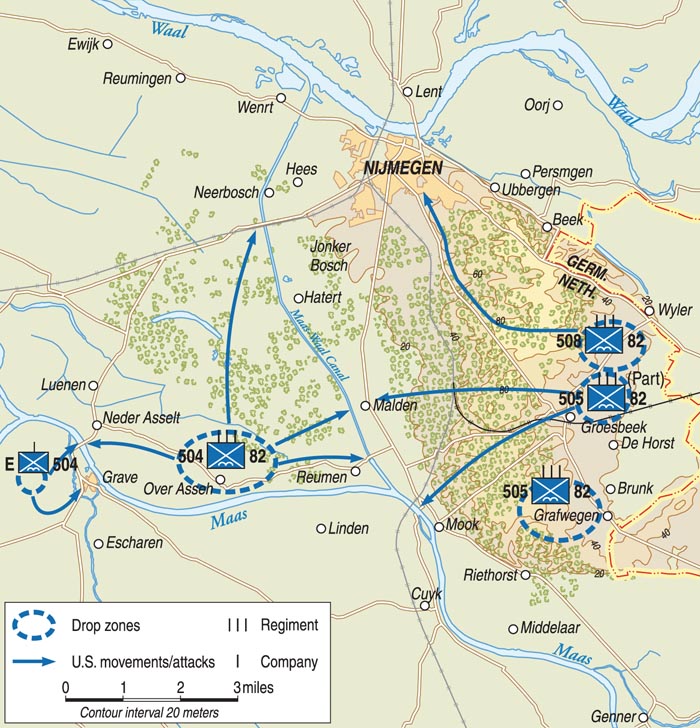

By late 1944, Brig. Gen. James Gavin’s 82nd Airborne was well on its way to establishing its reputation as one of America’s hardest fighting divisions. Operation Market Garden was the unit’s fourth combat jump, with previous airborne landings in Sicily, Italy, and Normandy. The division had three parachute infantry regiments— the 504th, 505th, and 508th—along with the 325th Glider Infantry and three artillery battalions using pack howitzers that could be air-dropped in bundles or landed in gliders. These formations would parachute into drop zones (DZs) generally to the south of Nijmegen and seize ground around the towns of Grave and Groesbeek as well as move against the larger town with its bridges over the Waal River. Once in control of its objectives, the division was to defend them until XXX Corps arrived to relieve them.

Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks’ XXX Corps was the spearhead for the British Second Army. During Market Garden the corps’ lead unit was the Guards Armoured Division led by Maj. Gen. A.H.S. Adair. It was equipped with a mix of armored vehicles including Sherman and Cromwell tanks, Daimler armored cars, and half-tracks. There was also ample artillery and air support available. The XXX Corps’ greatest handicap was the single road it was forced to travel down due to the wet and often boggy terrain, which kept the vehicles close to the road for fear of becoming mired. This made it easier for the defending Germans to target the British column.

Nijmegen was significant to the advance primarily due to its two bridges over the Waal River, which was 400 yards wide. One was a road bridge, the Waalbrug, and the other a railroad span, the Spoorbrug. Early in the battle these bridges were lightly defended by second-rate troops, but the German command quickly reinforced Nijmegen with experienced SS troops. There were a number of other German units in the area, including reserve, training, and police formations. Most of the German units were understrength and underequipped, but there were enough veterans to facilitate the hasty formation of battle groups known as kampfgruppen (KG) to improve the defense.

The airborne operation began on Sunday, September 17, 1944, and in most respects went well for the 82nd Airborne Division. Most of the troops landed close to their assigned landing zones, making it easier for units to assemble and move on their objectives. Colonel Reuben Tucker’s 504th quickly seized most of its bridges over the Maas-Waal Canal along with the Grave Bridge, which it attacked from both ends at once, resulting in a fast, relatively easy victory. Colonel William Ekman’s 505th dropped south of the town of Groesbeek and rapidly moved onto the nearby heights. Occupation of the heights brought a key defensive terrain feature under Allied control. The paratroopers there could protect against any enemy moves out of the nearby Reichswald, or National Forest. The 508th, commanded by Colonel Roy Lindquist, parachuted in south of Nijmegen and also seized nearby high ground and set up solid defensive positions. However, they did not move up the riverbank into Nijmegen to take the bridges. This would have severe consequences for the later fighting, although for unknown reasons the taking of the bridges was not assigned as high a priority as hindsight proved it should have been. The chance to capture the bridges before the Germans had adequate defenses prepared simply slipped away.

Initially, the Nijmegen area was populated by numerous German rear-echelon units and a few weak combat formations. This was exemplified by the fact that while 82nd Airborne captured only 156 prisoners the first day, they were from 28 different units. There were almost no prepared defenses within the town. German troops there included an NCO school company, a mixed antiaircraft unit of 20mm and 88mm guns, and two companies of reserve policemen and railroad guards. On September 17, these troops were reinforced by KG Henke, led by Oberst (Colonel) Fritz Henke, who normally led a parachute regiment. His force of four reserve companies combined with the existing garrison for a total of about 750 soldiers. It was too small a force to stave off a concerted attack by the American paratroopers, but more help was coming.

Later on September 17, the 10th SS Panzer Division “Frundsberg” was ordered to move from Arnhem to the Nijmegen area and attack the Allied airborne forces before they could consolidate their positions. They were to seize the bridges and prevent the paratroopers from linking with the advancing British. Several kampfgruppen were dispatched to Nijmegen to hold the bridges there. The first was KG Reinhold, set up on the north side of the Waal River, the opposite side from the attacking Allies.

Three more battle groups set up on the south side of the Waal, guarding the approaches to both bridges; a little more than 1,000 yards separated their southern spans. KG Henke, already arrived, set up around the south end of the Spoorbrug rail bridge. KG Euling took positions at the south end of the Waalbrug road bridge in a park known as the Hunnerpark, an old fort named the Valkhof, and a traffic roundabout leading to the bridge. Digging in between these two battlegroups was KG Baumgartel. The Germans had more than 3,000 troops between them, a mix of panzergrenadiers, reserve troops, combat engineers, and gunners for the hastily gathered antiaircraft and antitank guns. The division’s remaining artillery set up on the north side of the bridge while forward observers were placed in the front lines. Many, though not all, of the German troops were experienced Waffen-SS men. The German commanders ordered the bridges prepared for demolition but delayed destroying them in the hope they could be used to mount counterattacks later.

On the morning of September 19, the lead tanks of XXX Corps reached the 82nd Airborne and quickly moved toward Nijmegen. By now the German reinforcements were firmly in place, and it was apparent it would take more than the paratroopers’ light weapons to punch through the enemy lines south of the bridges. Generals Horrocks, Adair, and Gavin met to plan the next moves along with British General Frederick “Boy” Browning, the overall airborne commander. Gavin was still concerned about the thin American line near Groesbeek but was confident he could spare his reserve battalion, 2/505, commanded by Lt. Col. Vandervoort, for an attack on Nijmegen. The generals discussed the situation and decided 2/505 would join with elements of the Guards Armoured Division for a joint attack against the German defenses south of the bridges.

Two task forces were formed, one for each bridge. The eastern group was made up of Companies E and F of 2/505, most of No. 3 Squadron, 2nd Grenadier Guards, an armored unit, and No. 2 Company, 1st Grenadier Guards, a motorized infantry battalion. They would make an assault against the defenders of the road bridge. The western task force, which would attack the rail bridge’s defenses, included Company D 2/505, five Sherman tanks from No 3 Squadron, and a platoon of British infantry from the 1st Grenadier Guards. Reconnaissance troops from the 2nd Battalion, Household Cavalry Regiment (2/HCR) were also in the area. Both task forces had fighters from the local Dutch resistance to guide them through the narrow streets to their objectives. Dutch fighters also infiltrated the bridge area and several times cut wires to the demolition charges the Germans had placed. The Dutch also believed the Germans placed a switchboard for these demolitions in the town post office.

Vandervoort’s paratroopers linked up with their British counterparts and prepared to attack. Vandervoort was proud of his mostly veteran men and later stated, “Except for a few handpicked replacements, yet to be bloodied in combat, they were aggressive, skilled warriors. Their marksmanship, battle reflexes and survival instincts were finely tuned by being shot at—close and often. There were fraternal bonds between the battalion officers and men, especially the lieutenants. They were outstanding. They were raised to be last in the chow line and first out the door in the jump line.”

The entire force assembled at the Sionhof Hotel south of Nijmegen. At 1:45 pm, the column set out northeast up the Groesbeeksweg road toward Nijmegen. Two dozen Dutch resistance fighters accompanied them. They said there would be no resistance until about 600 yards south of the bridges, but the German positions were strong and included antitank guns. Nearer to the town the force would split into two parts for the final approach. Soon, however, the column was besieged by a different force: crowds of Dutch civilians who came out to greet the Allied soldiers as liberators.

Lieutenant James Coyle, a platoon leader in E Company, recalled it looked like a victory parade. “The Dutch people lined the roads in crowds that cheered us on our way.” Company D First Sergeant John Rabig was riding a tank with his men and recalled the adoration of the civilians as well, though they also provided a warning of sorts. “Dutch people were crowded along the sides of the road. The nearer we got to Nijmegen, the fewer people there were. Soon the people just disappeared and we were smart enough to know the shooting would soon start—and it did.”

The western task force split off toward its objective. Vandervoort stayed with the eastern group that captured the post office, which turned out to be empty. This made sense because it would have been foolish for the Germans to set up the explosives switchboard on the south side of the bridges. Along the way they were stopped by a Dutch woman who turned over a recently shot-down British pilot she was hiding in her house. She turned the flyer over to the Americans, even writing down the names of the men she gave him to. Afterward, the column moved on.

As the Allied attack got underway in earnest, reconnaissance troops from 2/HCR deployed to observe the flanks and gain observation over the river. They rode in small, nimble Daimler armored cars armed with a small 2-pounder (40mm) cannon. One of the British officers, a Captain Cooper, found himself under fire near some American paratroopers, who asked him to use his vehicle’s guns to support them. A pair of dug-in 88mm guns were firing away from across the river, so Cooper had his men return fire with their 2-pounders, driving the German gun crews away from their weapons. Their success was short lived, however, as a well-camouflaged 88mm opened fire from beyond the range of the diminutive 2-pounders. Cooper determined the gun’s position on his map and sent the grid coordinates to the Royal Artillery, just then coming into action. The very first salvo of six 25-pounder shells found the target, silencing it.

The Germans responded with a barrage of their own 105mm artillery. Cooper left his vehicle to take cover in an American trench. The shelling went on for an hour and a half, leaving Cooper deaf and covered in dust. He recalled, “This sort of shelling is perfectly bloody and gives you a splitting headache…. Every now and again the spandaus opened up from the other side of the river and bullets whistled over our heads. These American troops are splendid types— extremely brave, cheerful and indifferent to the worst. The bridge, an enormous, girdered affair, has been wired for blowing, which the ‘underground’ have twice cut, and is covered by every conceivable German weapon.”

As the reconnaissance troops dueled with the German guns, the task forces attacked. Lieutenant J.J. Smith of E Company was one of the first men in the eastern force’s attack. As he moved forward, German antitank guns opened a withering fire. “The Sherman tanks that were leading the attack ran into enemy resistance and were receiving extremely heavy fire from 88s…. The enemy immediately placed small arms and mortar fire on the lead elements of the infantry, which was 1st Platoon of Company E. All the mortar fire and artillery fire … came from this side of the bridge and it seemed to be observed fire. We later determined this to be true as we discovered snipers and enemy observers had radios and seemed to be in communication with the guns firing.” The British tanks, despite the incoming 88s, immediately began shooting into the nearby buildings, peppering the area with fire.

The Germans laid their defenses well. Camouflaged antitank guns covered all the intersections, and MG-42 machine guns, with the distinctive ripping sound of their high rate of fire, were set up in nests in houses around the guns so they could support each other. The lead British tank was quickly knocked out, along with one of the German antitank guns. Two more Shermans were soon hit as well, putting both of them out of the fight. The American paratroopers quickly fanned out into the surrounding buildings; it was suicide to fight in the open streets because the German fire was too heavy. The British infantry, bringing up the rear of the column, smoothly moved off to one side to attack the Germans on their flank, but interlocking machine-gun fire stopped them as well.

One of the Guard’s infantry platoon commanders, Lieutenant Dawson, found a house from which he could overlook the German defenders. He quickly brought up all the automatic weapons he had and directed their fire onto the enemy. A large number were killed and wounded, but one of their 88mm guns managed to return fire, scoring direct hits on the house. This forced the British troops to evacuate before it collapsed.

The Americans were also aggressively attacking. Most of the buildings were two-story brick and stone row houses, usually with attics and many with flat roofs. The paratroopers took advantage of this, moving from rooftop to rooftop and placing machine guns in the upper floors to cover the advance. Any German who exposed himself was greeted with machine-gun fire. The Guards’ Shermans went with them, adding their own machine guns to the fray. These fire teams supported other paratroopers, who used alleys, backyards, and windows to stay out of the line of enemy fire and turn their flanks. At times they would knock holes in the interior walls of homes and push forward without having to go outside.

The aggressive young airborne lieutenants controlled the action, keeping the assault squads on line. As soon as those men got into the targeted buildings, the support teams would join them to secure the houses and get ready to push on to the next one. Once a few houses in a block were taken, they would start bursting through walls to take the adjacent structures until an entire block was in their hands; then the process would be repeated on the next block. Private Carl Beck was a rifleman in Company E’s 1st Platoon. “We went into houses from the front and out the back, over the fence and into another house. Then out the front door, go across the street and into the front of another house.”

Lieutenant Colonel Vandervoort watched his men with pride and awe as they advanced toward the bridge. He was particularly impressed with the way they worked so closely alongside the British Guardsmen. “For soldiers of different Allied armies, it was amazing how beautifully the tankers and troopers teamed together.” All of them were veteran soldiers, and Vandervoort credited the Guards commander, Lt. Col. Edward H. Goulburn, with having trust and faith in his tank commanders to move off on their own to support the Americans. The tanks moved up alleys and through yards to fire on enemy positions. It took a lot of initiative and skill to stay together and not let either tanks or infantrymen expose themselves by getting too far ahead of the other. Still, the Germans fought with similar courage, and despite the best efforts of the Allied task force, the attack was halted short of the bridge as darkness arrived.

The western task force had its own ordeal. The smaller force worked its way through the narrow streets, skillfully guided by the Dutch resistance, until it was only 200 yards from the southern end of the railroad bridge. With dusk approaching, the column attacked immediately, hoping to storm through before the coming night impeded them. As the Shermans joined the infantry in the assault, two of them were knocked out by accurate fire from antitank guns on the other side of the river. The infantry took heavy fire from German troops dug in on the railroad embankment and in several houses around it. It was a tough strongpoint well supported with artillery fire, and the Anglo-American attack stalled. The infantry fell back a short distance, took cover in a number of houses, and dug in, assuming they would be counterattacked during the night. This was a common German tactic, and the experienced troops expected fast counterattacks. The eastern task force also expected a night action and prepared for it.

That night, however, they were gratefully disappointed. Even the SS panzergrenadiers were rattled by the sudden appearance of tanks and infantry, since they thought there were still more German troops ahead of them. During the night they set fire to several houses to provide light in case of a renewed Allied attack, and the troops around the railroad bridge pulled back, shrinking their perimeter. The Germans were still determined to hold the south ends of both bridges but they were unwilling to advance and risk cutting off their only avenue of escape across those bridges. September 19 ended in stalemate.

Once General Gavin learned of the setback, he created a new plan. If they continued attacking the bridges from the southern end, it would take time, and the Germans would probably destroy the bridges rather than lose them to the Allies. Gavin knew the best way to take a bridge was from both ends at once, so he decided to put a force across the river and assault the northern ends of the bridges while the task forces on the southern end continued putting pressure on the defenders there. He took the plan to Generals Browning and Horrocks. Browning approved the idea, but the airborne troops had no boats available, and the Germans had stripped the river of all local craft.

Horrocks, however, had 32 boats in his engineer units and ordered them forward, giving them priority to move up along the narrow roadway XXX Corps was using for its advance. The boats were supposed to arrive at 8 am on the 20th, but traffic jams along the road delayed their arrival until 2 pm. Gavin wanted to start the crossing in the morning, but the late arrival of the boats meant the crossing had to go at 3 pm.

The plan involved sending a battalion across the river downstream from the bridges. Major Julian Cook’s 3/504 was available, recently relieved of defensive duties by troops from XXX Corps. H and I Companies would go in the first wave, accompanied by a few men from Headquarters Company, including Major Cook. The second wave would bring G Company and the rest of the headquarters troops. While 3/504 crossed the river, 2/504 would provide covering fire from the south bank. The 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion would also support the crossing with its pack howitzers, joined by all available British artillery, more of which arrived each hour. The artillery would fire a 10-minute preparatory bombardment on the German defenses. Afterward, fighter-bombers would strafe and bomb the enemy for 10 more minutes, from 2:45 to 2:55. As soon as the planes were finished, the artillery and mortars would fire smoke shells to cover the crossing. Tanks of the 2nd Irish Guards would also give fire support and fill any gaps in the smoke screen with their own smoke rounds.

Once on the far bank, the paratroopers would have to cross up to 800 yards of open field to an embankment with a dike road atop it. There were German defensive positions along this dike, and once there part of 3/504 would establish blocking positions and patrols to the north and west while the rest attacked eastward toward the bridges. They would reach the rail bridge first and move on to the road bridge. Meanwhile, the task forces on the south sides of the bridges would attack in force to break through, enabling the combined Allied forces to capture them. It was risky plan, but the American paratroopers understood the dire straits their British counterparts were in at Arnhem. A short, intense assault would incur heavy casualties but save lives in the long run.

The task forces renewed their attacks on the south side of the Waal on the morning of September 20, while 3/504 waited for the boats to arrive. They were methodical, gradually tightening the cordon around the southern approaches to the bridges. At about 2:30 pm, as the tanks were moving into position to support the crossing, the trucks bearing the boats arrived. One was hit by German fire as it approached the riverbank, reducing the number of boats to 26.

Major Cook’s men realized how risky the river assault would be, but once they laid eyes on the boats the situation became even more serious. The craft were known as “Goatley” boats, collapsible affairs made of wood and canvas, weighing 200 pounds and about 19 feet long. Each could carry 13 troops with three engineers. The engineers had to assemble them, and the paratroopers helped as the time to launch the attack grew near. Each boat should have had eight oars, but some had only two; the paratroopers would have to row using rifle butts.

The artillery preparation went off as planned, and soon it was time to go. Cook and his men rushed down to the riverbank, manhandling the boats into the water and climbing aboard. Smoke covered the far bank as the tanks and mortars sent more smoke rounds sailing overhead.

Captain Moffatt Burriss commanded I Company. He and his unit hid behind a berm most of the day and had yet to see the river they would cross. “We were not shown the river before crossing. We waited the other side of the levee most of the day. Had we seen what we were expected to cross in daylight, we probably wouldn’t have done it! I still wonder how any of us survived the crossing.”

The Germans contested the assault as soon as they perceived it. Lieutenant Thomas Pitt watched the air support roar in. “Two Spitfires [actually Typhoons] came over and started to strafe the opposite banks … where the Krauts were dug in. About the second pass, the Germans got one of the Spitfires and the other one went home. So that was the end of the air cover.” Pitt also watched British tanks move up and start firing smoke and high-explosive rounds. “They opened fire and they put a lot of iron down in a short period, but in a couple of minutes the counterbattery came.” German artillery from the north side of the river began answering the Allied attack. Luckily for the British tankers, most of the 88mm guns were sited for antiaircraft work and could not bear on the tanks as they used rubble around some factory buildings and a power station for cover.

The men in the boats paddled into the smoke covering the river. The Germans knew the smoke meant a crossing and poured fire into it using machine guns and 20mm flak guns along with the artillery. The paratroopers frantically paddled across the 400 yards of the river, aware of how vulnerable they were. Soon the smoke started clearing in the breeze, fully exposing them to enemy view. Incoming fire now poured in with even greater accuracy. The 20mm flak guns were particularly bad; a single hit would blow a man’s body apart, showering blood and viscera. Halfway across, the boats were within mortar range and bombs showered down. One hit a boat directly, blowing it apart and leaving the survivors in the water, festooned with heavy ammunition and equipment. The other boats could not stop to help them.

Browning and Horrocks observed the crossing from the roof of the power station. They watched as boats were blown apart, sank, or drifted downstream with their occupants dead and dying. It was a horrible scene, but as they watched the survivors kept going. They paddled with rifle butts or used their helmets and kept as low as they could, desperately racing for the far shore. Suddenly, they were there. Boats grounded on the far bank, and paratroopers poured from them, running for the embankment. Only 13 boats reached the shore, but once they were empty the engineers pushed off and began paddling back through the torrent of steel and fire to pick up the next wave. Eleven made it back. Meanwhile, the tankers began spotting the deadly flak guns and targeted them; most were emplaced in an old fortress called the Hof Van Holland.

On the north bank only 125 paratroopers were still able to fight, but they quickly formed into small groups and attacked the German defenders. The Americans were enraged; they had endured utter hell crossing the Waal and seen many friends lost. Now they assaulted the dike with fury and rage. Captain Burriss ordered his men to shower the dike with grenades. A flurry of explosions thundered across the enemy-held embankment and broke their spirit. Paratroopers followed the blasts and tore into the defending Germans, some of whom were aged reservists and others teenage boys. Burriss recalled that the enraged paratroopers took no prisoners, even when Germans tried to surrender. Within 30 minutes the dike was in American hands.

Some paratroopers set up defenses along the dike while others, gradually being joined by the following waves, formed up to move on the bridges. Major Cook and a captain took over a group of 30 men and immediately moved against the rail bridge. They kept the enemy off balance by constantly attacking, keeping the pressure on until the enemy broke and ran. There were only five boats left after the final trip across, and the newly arrived paratroopers joined their comrades in the attack, fanning out toward the bridges and the remaining enemy strongpoints.

First Lieutenant James Magellas led a squad-sized group against the Hof Van Holland fort, which held the flak guns that had so decimated the paratroopers during the crossing. Magellas had lost half his platoon in their boat, which had been hit by mortar fire. He ordered his men to fire at the flak and machine guns until the German were suppressed, and then the Americans charged ahead, throwing grenades. This drove the Germans inside the fort, where they remained while Magellas and his men disabled the guns. The Germans would continue to resist the rest of the day until follow-on troops from 1/504 cleared the fort, taking 30 prisoners.

Other groups reached the Spoorbrug rail bridge and ran into stiff resistance, but each German strongpoint was taken in turn. A 19-man force led by Lieutenants Edward Sims and Richard LaRiviere reached the northern end of the bridge after neutralizing the last scattered enemy positions, only to find a new threat. About 500 Germans, those who remained of the defenders at the southern end of the bridge, were now moving across it. Having seen the success of the river assault, they realized their only avenue of escape was about to be cut off and chose to retreat before the paratroopers could consolidate their blocking positions.

Captain Carl Kappel of H Company watched their desperate attacks. “These units made several counterattacks … which were easily dealt with…. Two German machine guns were mounted to sweep the long axis of the bridge and the German situation was now hopeless. One of the German prisoners who could understand English was ordered out on the bridge to tell the Germans to cross to the south side and surrender. He was shot by the Germans pinned on the bridge. They were again swept by machine-gun fire, and many leapt from the bridge, even though they were not over the river. None surrendered at this time.” The paratroopers even fired at enemy soldiers leaping from the bridge, trying to hit them in midair. Kappel finally ordered them to stop, as it was a waste of ammunition.

A total of 267 bodies were recovered from the bridge with many more lost below. Staff Sgt. David Rosencrantz recalled that while the fighting was shorter than Sicily, Salerno, and Anzio, “it was tougher and bloodier while it lasted.” The rail bridge was now firmly in Allied hands. LaRiviere left Sims to oversee the rail bridge while he and Captain Burriss set out toward the Waalbrug road bridge, clearing houses as they went. They were soon joined by Lieutenant Magellas and his men. All of them came under fire from troops on the bridge itself, but they battered their way onto the northern end despite being almost out of ammunition.

On the south end of the Waalbrug the Grenadier Guards and paratroopers saw the Americans on the other side and launched a concerted attack at 5:30 pm. They soon overran the last of the SS troops in the Hunnerpark and Valkhof, and a small force was dispatched to fight its way across the bridge and link up with the 504th men. No. 1 Troop of No.1 Squadron, 2nd Grenadier Guards set out led by Sergeant Peter Robinson. The squadron commander, Captain Lord Peter Harrington, would follow in his own tank along with a scout car carrying an engineer, Lieutenant A.C.G. Jones, who would check the bridge for explosives.

As they moved onto the bridge’s ramp, the crack of an 88mm gun sounded, and a round struck the pavement in front of the lead Sherman. It ricocheted into the tank, damaging it and knocking out the radio. As Robinson quickly reversed, two other Shermans spotted the muzzle flash and silenced the gun before it could do any more damage. Sergeant Robinson changed tanks, and the troops raced onto the bridge. The Germans opened fire with all they had, including panzerfaust antitank weapons fired by soldiers hiding among the bridge’s upper girders. The tankers elevated their coaxial machine guns and watched dead and wounded Germans tumble from their hiding places onto the pavement below.

At least five antitank guns on the north bank also opened fire. The British pushed ahead anyway and soon arrived at a concrete roadblock covered by another antitank gun. Robinson’s tank charged through, and his gunner, Guardsman Leslie Johnson, wrecked the enemy gun with three well-placed rounds. Some infantry broke cover and ran, only to be cut down by the tank’s machine guns. The British tanks were now across the bridge and roaring down the opposite ramp.

As Robinson advanced down the street, a German self-propelled gun appeared and opened fire. One of the rounds exploded nearby and blew off Robinson’s helmet, but gunner Johnson fired several rounds of his own, leaving the enemy vehicle burning. They went another three quarters of a mile, blasting German infantry fighting from a church and forcing them to retreat. Soon afterward, grenades from a nearby ditch hit Robinson’s tank, and he responded with his machine gun, firing a few rounds before realizing the men wore American helmets. He stopped shooting, and they linked up. Fortunately, no harm was done in the incident. Only his tank and one other made it this far; the other two were knocked out on the bridge, though one later rejoined the troop.

On the bridge, Lieutenant Jones dashed around cutting wires and removing detonators despite enemy sniper fire. Some of his men arrived, and they continued the search, discovering 81 Germans hiding in compartments in the bridge piers. All of them were fortunate that day. The commander of 10th SS Panzer Division, General Heinz Harmel, watched the attack go in from a bunker upstream from the road bridge. That bunker held the demolition switchboard, and as he watched the British tanks race across the bridge in the waning daylight he ordered the Waalbrug blown just as the British reached the center span. Nothing happened, even when they tried again with the reserve circuits. No one is sure why, but many believe the wires were cut by a Dutch resistance fighter who died during the battle. Whatever the cause, two more bridges now belonged to the Allies.

Tragically, the effort made to seize the Nijmegen bridges came to nothing. The British paratroopers trapped near Arnhem were not rescued. The defenders were resisting too skillfully, and the attackers were hard pressed to maintain the required pace on the single narrow road. Arnhem proved to be the bridge too far, memorialized in books and film. The Nijmegen bridges, however, did prove within Allied grasp, but only through the extreme courage and sacrifice of a combined force of American paratroopers and British Guardsmen who were willing to risk everything to save fellow soldiers they had never met.

Author Christopher Miskimon is a regular contributor to WWII History. He writes the regular books column and is an officer in the Colorado National Guard’s 157th Regiment.