By Brent Douglas Dyck

By 1936, 18-year-old Hildegard Koch had reached a crossroads in her young life as she finished her schooling. Her leader in the local Bund Deutscher Mädel (the League of German Girls), gave her some advice: “If you don’t know what to do, why not give the Führer a child? What Germany needs more than anything is racially valuable stock.” It was the first time that Koch had heard of the Lebensborn Program.

In 1933, the year Hitler and the Nazis came to power, the birth rate in Germany was 14.7 per 1,000 people. This was less than half what it had been at the turn of the century. Additionally, there were hundreds of thousands of abortions performed in Germany every year. These two practices alarmed the Nazi regime. The Nazis needed children if they were to accomplish the two goals of Nazi ideology: conquer territory in the East and establish Aryan supremacy over Europe. Healthy young boys were needed to grow up to be soldiers in the German Army. Healthy young girls were needed to grow up and give birth to the next generation of super soldiers.

Heinrich Himmler, the leader of the SS, founded the Lebensborn Program on December 12, 1935. Lebensborn means “the fountain of life.” The program actually provided three services: it gave pregnant women, either married or unmarried, a place to give birth to their babies and receive the best medical care; a meeting place for men and women of true Aryan stock to create babies for Adolf Hitler; and a place to raise children who had Aryan features after they had been kidnapped from their parents from foreign countries.

Himmler explained the main purpose of the Lebensborn program in an undated letter to Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel. “Official statistics show that there are still some 600,000 abortions annually in Germany. I have been concerned for years about the fact that many abortions occur among those who can be counted as the best sections of German society. I do not believe that we can tolerate a situation where annually hundreds of thousands of valuable girls and women are lost as mothers of German stock because they have illicit abortions whose effect is often to render them sterile … the aim of protecting German blood, however, has the highest priority.

“It is interesting to think that, if we could prevent this scourge of abortion, and therefore give the German nation annually more than 600,000 children who would not otherwise be born, this population policy measure alone would result in 18 to 20 years in 200 more regiments for the army. An extra 500,000 to 600,000 Germans each year would create a commensurate amount of wealth. The strength of our soldiers and workers would make a considerable contribution that would guarantee the maintenance and enhancement of Greater Germany.

“It was with these considerations in mind that I founded ‘Lebensborn’ as a registered association in 1936. ‘Lebensborn’ leads the campaign against abortion in a positive way. In the Lebensborn homes, which are scattered all over the nation, any German mother of good blood can await in serenity the hour when she commits her life to the nation.”

The first Lebensborn home was opened in 1936 in Steinhöring, a tiny village outside Munich. Eventually, the Lebensborn program would establish more than 25 homes across Europe: 10 in Germany, nine in Norway, two in Austria, and one each in Belgium, France, Luxembourg, Holland, and Denmark. In order to be accepted into the Lebensborn program, women had to prove that they were pure Aryans going back for at least three generations on both sides of their family. Due to this, about 60 percent of applicants were turned away. The majority of the women accepted were unmarried, although married women were accepted as well, as long as they passed the racial purity test.

The homes were decorated with furnishings that were confiscated from the homes of Jews that had been sent to concentration camps. Sometimes, the women in the homes were encouraged to sing communal songs, watch Nazi propaganda films, or attend ideological lectures. This was all done with the aim, according to one historian, “to make the women into even better Nazis than they were when they arrived.”

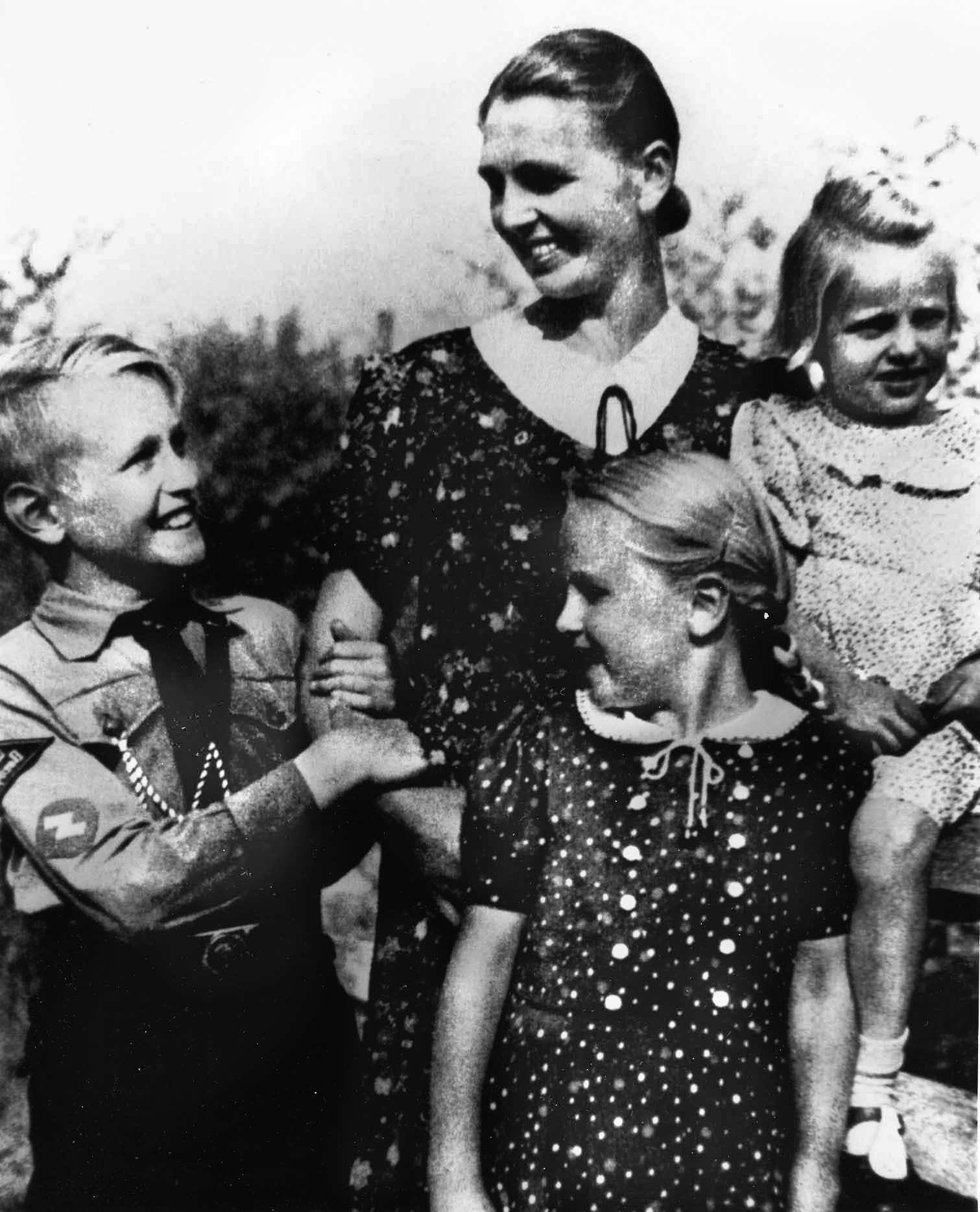

Children born on Himmler’s birthday were given special gifts. At birth, they received a candlestick, and on every birthday, a gift of one mark was put into their savings account. One mother, Käthe Sayrl, took the time to write a letter to Himmler. She wrote, “Thank you for your good wishes on the birth of my third Lebensborn child. The candlestick for little Helga has arrived safely, also the six bottles of Vitaborn juice. Please express my gratitude … from me and my husband. I enclose a picture taken at Christmas of three contented little girls—Gisela (October 1940), Dietlind (May 1942), and Helga (October 1943) … Everyone realizes what a marvelous thing I have done, because in the course of this war, people have come to understand that you can’t offer anything more worthwhile than a whole brood of children … total war has only one response today—everything must be done for victory.”

The Lebensborn program also acted as a sort of brothel that encouraged sex between SS men and suitable Aryan women, such as Hildegard Koch, to create “racially valuable” offspring. According to Himmler’s physical therapist, Felix Kersten, Himmler told him in 1943, “I have made it known privately that any unmarried woman who is alone and longs for a child can turn to Lebensborn with perfect confidence. I would sponsor the child and provide for its education. I know this is a revolutionary step, because according to the existing middle-class code an unmarried woman has no right to yearn for a child…Yet she often cannot find the right man or cannot marry because of her work, though her wish for a child is compelling. I have therefore created the possibility for such women to have the child they crave. As you can imagine, we recommend only racially faultless men as ‘conception assistants.’”

Possessing blond hair and blue eyes, the very features the SS was after, Koch was a perfect candidate for Lebensborn. She volunteered enthusiastically. As with other candidates, she was carefully screened through a series of medical tests and background checks. Any case of hereditary disease, mental illness, or any hint of Jewish ancestry would have disqualified her. Given the seal of approval, Koch was taken to a castle near Tegernsee in Bavaria. She later said, “There were about 40 girls all about my own age. No one knew anyone else’s name, no one knew where we came from … We had to sign an undertaking renouncing all claims to the children we would have there, as they would be needed by the state and would be taken to special houses and settlements” to be raised.

At the castle, she was introduced to many blond-haired, blue-eyed SS officers. The SS officers may already have been married, but this was irrelevant. They were given leave from the fighting at the front to go to Lebensborn homes and do their “duty” for the Fatherland. Koch explained what happened next to author Louis Hagen. “They were all very tall and strong with blue eyes and blond hair … We were given about a week to pick the man we liked and we were told to see to it that his hair and eyes corresponded exactly to ours. We were not told the names of any of the men. When we had made our choice, we had to wait until the tenth day after the beginning of the last period, when we were again medically examined and given permission to receive the SS men in our rooms at night … He was a sweet boy, he had smashing looks. He slept with me for three evenings in one week … As both the father of my child and I believed in the importance of what we were doing, we had no shame or inhibitions of any kind … The other nights he had to do his duty with another girl.”

Koch became pregnant and was moved to a maternity ward for the next nine months before giving birth to a healthy baby boy. She nursed the baby for two weeks, and then he was taken away and adopted by an SS family. Koch never saw her child or the boy’s father again.

Guntram Weber was one of the children born through the Lebensborn program. Weber never knew who his father was when he was growing up in Germany. His mother only told him that his father was a lowly truck driver for the Luftwaffe, and he had never fired a gun during the war. She told him that his father died in Croatia when he drove over a landmine. When Guntram was a teenager, he was rummaging through an old box and came across a silver cup. It was a baptism present with Guntram’s name on one side. However, on the other side it was inscribed, “From your godfather, Heinrich Himmler.”

Guntram would find out years later that his father was SS Maj. Gen. Ludolf von Alvensleben. Alvensleben had four children with his wife, but he also fathered another child, Guntram, as part of the Lebensborn program. Alvensleben had been responsible for conducting mass executions in Poland. After the war, he fled to South America, and he was sentenced to death in absentia by a Polish court in 1949. He died in Argentina in 1970.

Weber was horrified by the revelation. He said, “I had to struggle with the fact he was a murderer and that was incredibly difficult. I had to check my position vis-à-vis myself. Was there any murderous instinct in me too? It was harrowing.”

It is believed that about 8,000 children were born in Germany, and another 12,000 were fathered in Norway as part of the Lebensborn Program. After the war, those children who had a Norwegian mother and a German father were subject to years of abuse. A leading psychiatrist recommended that the Lebensborn children should be locked up in mental institutions because they were “genetically bad” since they had German genes. Many of these children were physically and sexually abused in government homes. A priest recommended that these Lebensborn children be sterilized to prevent them from becoming Nazis and waging war in the future.

Harriet von Nickel, born in Norway in March 1942, suffered years of abuse after her mother agreed to have a child with a German officer as part of the Lebensborn program. Taken in by a foster family after the war, she was chained up with the dogs in the yard. When she was six years old, a man from her village threw her into a river. He wanted, he said, to “see if the witch would drown or float.” When she was nine, drunken fishermen carved a swastika into her forehead with a nail.

“In the Norwegian population, there was a hatred directed at us children,” explains Bjorn Lengfelder, a Norwegian Lebensborn child. “A small brother and sister, five years old, were placed in a pig sty for two nights and two days. Then in the kitchen, they were put in a tub and scrubbed down with acid until they had no skin left ‘because we have to wash that Nazi smell off you.’”

Lebensborn was also responsible for the kidnapping of children deemed “racially valuable” from occupied countries. After the Germans conquered Poland in September 1939, the Nazis noticed that there was a surprising number of blond, blue-eyed, fair-skinned children in that country. Himmler and his SS believed that these Polish children were actually Aryans who rightfully belonged in the Third Reich. In October 1943, Himmler said, “Obviously in such a mixture of peoples, there will always be some racially good types. Therefore, I think it is our duty to take their children with us, to remove them from their environment, if necessary, by robbing or stealing them.”

The SS would visit all of the orphanages and schools in a city and round up all of the children. The children would then be sent to a medical center where they would be lined up, have their pictures taken, and then undergo inspection by SS doctors regarding 62 physical characteristics. These characteristics were not only the color of their hair and eyes, but also the width of their nose, thickness of their lips, their height, and their posture. Girls’ hips were measured to see if they were good child-bearers. The children were then ranked into different racial categories. Those children who had the least Aryan characteristics were sent to the special children’s camp at Lodz or to concentration camps.

Those children with the most Aryan characteristics were sent to Lebensborn homes, where they would be “Germanized.” The goal was to erase all traces of the child’s Polish heritage. They would learn the German language, and their birth certificates would be falsified. They would now have a German name instead of a Polish one, and they would have a German place of birth. Once they were suitably “Germanized,” they would be available for adoption by a suitable SS family. The SS families, as well, were purposely kept in the dark and made to believe that they had adopted an orphaned Aryan child.

Ingrid von Oelhafen was a 15-year-old girl who was walking down the street in Hamburg after the war when she came across a Red Cross poster. The poster was captioned, “WHO KNOWS OUR PARENTS AND OUR ORIGINS?” When she looked at the poster, she became astonished. One of the pictures was a baby photo of herself. Later in life, she went through an old chest of her mother’s and found a receipt from a Lebensborn home made out to the von Oelhafens to adopt a two-year-old girl. Her real name was Erika Matko, and she had been taken away from her parents in Cilli, Yugoslavia, in August 1942, when she was only nine months old because she was deemed racially valuable.

She was sent to the Lebensborn home in Kohren-Sahlis, where she stayed for almost two years. She learned to speak German from the nurses there before the von Oelhafen family adopted her. In an unusual twist, the SS gave the Matko family a replacement baby girl, whom they also named Erika. Where this girl came from is a mystery.

It is believed that approximately 200,000 children were stolen over the course of the war by the Nazis in Poland, Yugoslavia, Ukraine, Hungary, and Romania. After the war was over, a team headed by Dr. Roman Hrabar worked with the United Nations to try to reconnect these Lebensborn children with their rightful parents. It is estimated that only a small fraction of these stolen children were ever reunited with their biological parents.

In many instances, the paperwork was lost and they could not be traced. In other cases, either the German families or the children themselves refused to believe the truth. It is estimated that there are now hundreds of thousands of descendants of these children who were stolen by the Nazis during World War II.

Brent Douglas Dyck is a history teacher in Bradford, Ontario and a frequent contributor to WWII History.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments