By Mark Simmons

“At Tarnopol we endured heavy Russian fire but in Normandy we were hit again and again, day after day by British artillery that was so heavy the Frundsberg [10th SS Panzer Division “Frundsberg,” named after 16th-century German knight and general Georg Von Frundsberg] bled to death before our eyes. It was worst during an attack, theirs or ours, when we would be terribly blasted. I saw grenadiers struck dumb and unable to move and others made mad by the increasing ‘drumfire.’”

So recalled Gunter Balko, an infantryman in the 21th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment, who went on to say that the British artillery was his worst memory of Normandy, when he was fighting for Hill 112.

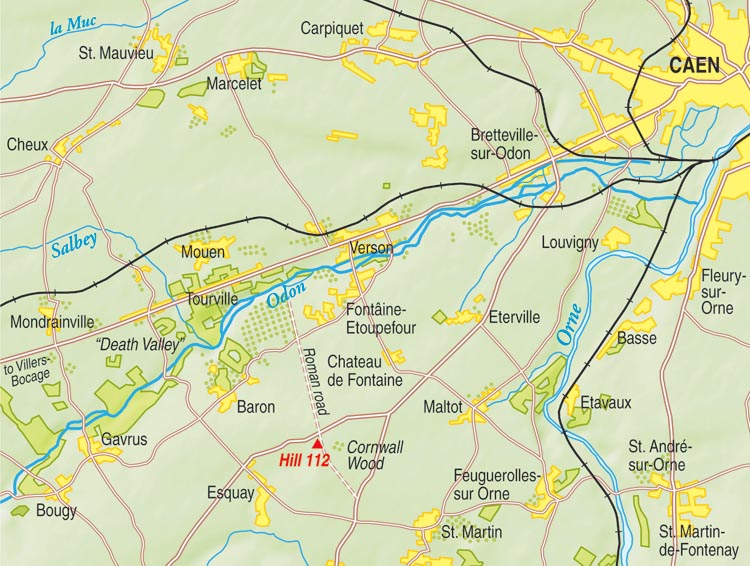

The ground in Normandy over which the fight for Hill 112 took place in July 1944 lay to the southwest of Caen between the Odon and Orne Rivers. The River Odon is small, no more than a stream in places, running through a narrow, steep-sided valley lying north of the area and has few crossing places. The banks, hedges, and steep sides of the river represented a difficult obstacle for tracked and wheeled vehicles to cross. Rising from the valley are the open slopes of Hill 112, gentle slopes hardly seeming to dominate. But from the hill, observation is impressive.

The River Orne, larger than the Odon, forms the eastern and southern boundary. The flanks of Hill 112 sweep down into a broad valley through which the river flows. Beyond was the tempting goal the Allies sought: the open plains of northern France, ideal tank country. Interspersed in the area were farms and villages, the buildings well built from local honey-coloured limestone.

General Bernard Montgomery, commander of the Allied forces in Normandy, had, between June 7 and the end of the month, directed three operations to take Caen—first by the 3rd Canadian Division on June 7-8. According to one historian, the Canadians had “come off second best” against the 12th SS Panzer Division “Hitlerjugend,” which fought with fanatical courage.

The Allies had benefited from the great success of Operation Fortitude, the deception plan that had fooled the Germans into holding most of their forces in the Pas de Calais area believing Normandy to be a feint. However, on June 9, the 12th SS and 21st Panzer Divisions were joined by the Panzer Lehr Division after a 90-mile drive,during which it had been repeatedly attacked by Allied air forces. These three divisions now formed the main German force around Caen.

On June 13 came the Villers-Bocage operation in which Montgomery committed his veteran Eighth Army divisions: the 51st Highland and 7th Armoured (the “Desert Rats”)—the latter with four regiments and nearly 300 tanks. The Highlanders would attack southward east of Caen toward Cagny, while 7th Armoured would attack through Tilly and toward Villers-Bocage.

Then British 1st Airborne Division, still in England, would be dropped south of Caen and link up the two prongs, thus surrounding Caen. However, warned by the Ultra decodes from Bletchley Park of the impending counteroffensive by the Germans, Montgomery decided against committing the airborne troops, but he still decided to launch the attacks on both sides of Caen to forestall the Germans and keep the pressure on them.

On June 10-12, the 51st Highlanders pushed inland toward Cagny but soon found there was little hope of reaching it against the determined opposition of 21st Panzer, reinforced by elements of the 346th and 711th Divisions. On June 11, the Highlanders’ attack was brought to a halt. The 5th Battalion, Black Watch Regiment went into action at 4:30 AMand suffered 200 casualties in an attempt to reach Bréville. The unit history recalled, “Every man of the leading platoon died with his face to the foe.”

The next night the 12th Battalion of the Parachute Regiment took Bréville at a huge cost. Of the 160 men that went into action 141 became casualties, but they closed an alarming gap in the line. After this the offensive ground to a halt.

Meanwhile, 7th Armoured made slow progress south from Tilly toward Villers-Bocage. It was the first venture into the soon to be infamous Normandy “bocage” country—thickly banked hedgerows enclosing small fields separated by narrow winding lanes, many of which were lower than the surrounding fields. The countryside was ideal for antitank defense.

The bocage country into which the Desert Rats moved was defended by Lt. Gen. Fritz Bayerlein’s Panzer Lehr. It was a strong division but had 10 miles of front to cover with its two tank and four infantry battalions.

Major General W.R.J. (Bobby) Erskine, commander of 7th Armoured, commented as his men moved off that he “never felt serious difficulty in beating down enemy resistance.” However, enemy resistance increased and slowed Erskine’s progress at Tilly on June 11. A gap was found in the German line between Caumont and Villers-Bocage, so 7th Armoured swung westward to exploit the hole, but the British were advancing on a narrow axis.

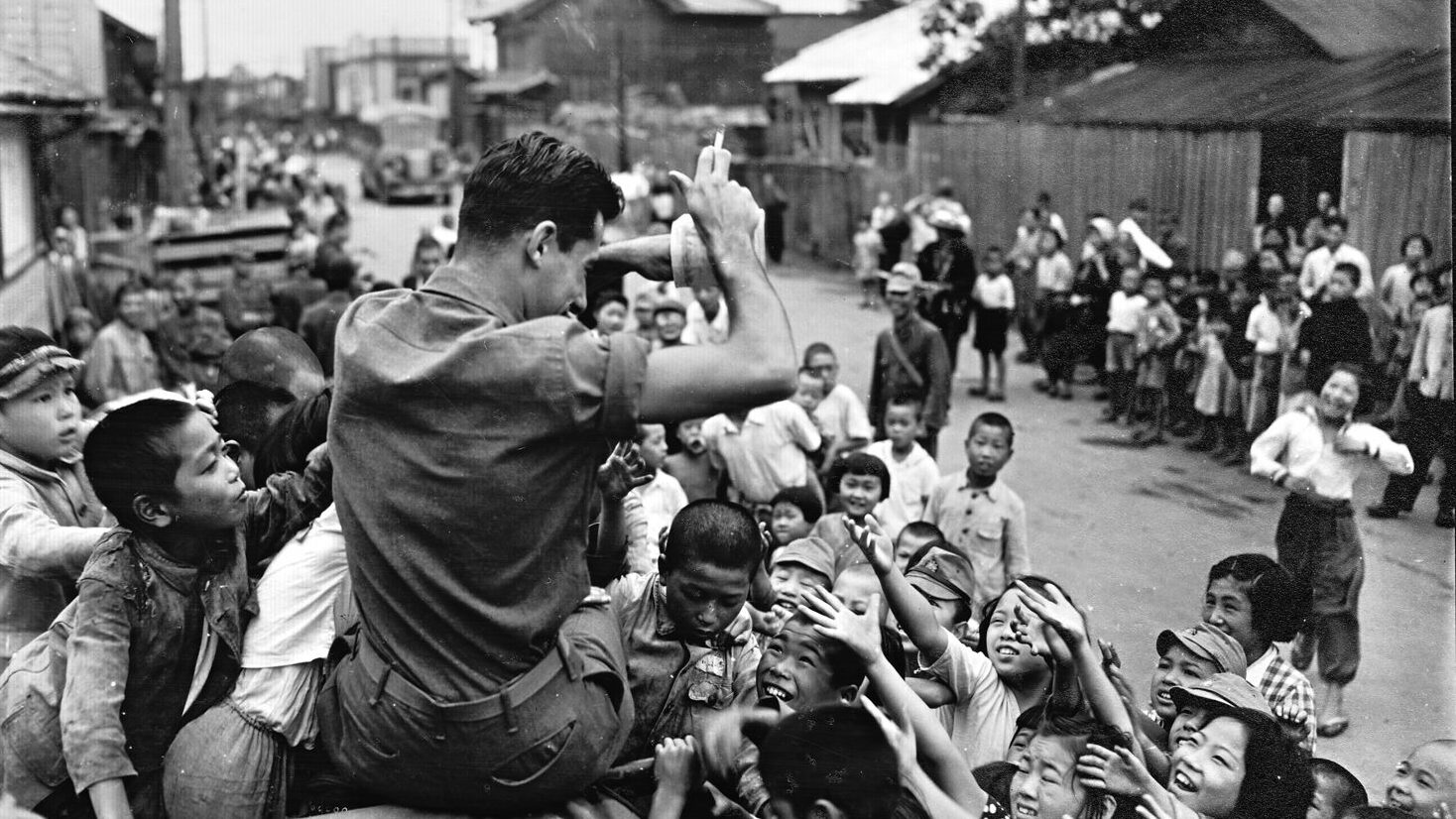

It took the British four days of bitter fighting to reach Villers-Bocage, losing men and tanks along the way. Early on the morning of June 13 they entered the town to be greeted by its exuberant population. The advanced guard of the 4th County of London Yeomanry and a motorized company of the Rifle Brigade headed out of the town toward the high ground of Point 213 and the road to Caen. There they were ambushed by the Tiger tanks of the 501st SS Heavy Tank Battalion.

The commander of the 501st’s leading company was none other than Obersturmführer Michael Wittmann, who had won the Knight’s Cross on the Eastern Front, where he had knocked out 117 Russian tanks. Hidden in woodland, he observed the leading elements of 7th Armoured leaving Villers-Bocage and allowed the British to approach close to his position before opening fire, destroying the leading Cromwell tank. He then left cover, confident in the Tiger’s armor, and motored along the column, systematically destroying tanks while his machine guns dealt with the motorized infantry.

The 8th Hussars reconnaissance company came to the aid of the London Yeomanry. However, as they came into view the four other Tigers of Wittmann’s company engaged them and drove them off. A second Tiger company soon joined Wittmann and entered the town. The British 6-pounder antitank guns were largely ineffective against the Tigers, but Wittmann’s own tank was stopped when a track was blown off.

In the narrow streets of Villers-Bocage, the Tigers began to fall victim to close-range weapons of the British infantry. After two Tigers were set on fire, the rest withdrew. Later that day, infantry of the Panzer Lehr retook the town while 7th Armoured fell back toward Tilly.

Erskine and Montgomery, having gained intelligence that another panzer division, the 2nd, had been identified in the area, approved the withdrawal. It was the first German armored division to reach Normandy from outside the area, moving from its base at Amiens.

On June 17, Adolf Hitler made his only visit to the French front at Margival, the underground German headquarters near Soissons. The purpose was to encourage his commanders, Erwin Rommel, head of Army Group B, and Gerd Von Rundstedt, commander-in-chief in western Europe (OB West). Hitler told them that reinforcements were on the move from Russia and the flying-bomb attacks on London were to be intensified.

Rommel spoke up and pointed out that the power of the Allied air forces and naval gunnery made counterattacks in strength extremely difficult. He felt a withdrawal out of range of the naval guns would be prudent and the bocage country would aid the defense. Hitler, to whom the word “withdrawal” was anathema, would not hear of it. Later, Rommel bravely suggested Germany should try to make peace with the Allies. Hitler screamed at him that it was a question “which is not your responsibility.”

That evening a flying bomb in which the Führer had so much faith went out of control after being launched and hit the Margival compound. Hitler, protected by more than 20 feet of reinforced concrete, was not injured, but the close call convinced him to leave, canceling his planned visits to Rommel’s front. He never returned.

A great storm on June 19-23 affected the Allied buildup, costing them 140,000 tons of stores. Montgomery rejected a new offensive east of the Orne, for he realized that committing single divisions would achieve little. Instead, he waited to commit the entire VIII Corps on a four-mile front between Carpiquet and Rauray, toward the wooded banks of the Odon. Three fresh divisions—15th Scottish, 43rd Wessex, and 11th Armoured—would be committed to Operation Epsom under Lt. Gen. Sir Richard O’Connor.

The Germans had nearly three weeks to prepare the defense, making good use of embanked hedgerows, sunken lanes, woods, and sturdy stone buildings. It was five miles deep with interconnecting positions, which gave supporting zones of fire from a honeycomb of machine-gun nests. There was a second line two miles behind this with heavier weapons.

Starting on June 25, Operation Epsom was slow going for the British. The narrow corridor they advanced into found too many troops fighting off a single road. Thus VIII Corps was unable to deploy enough troops against the determined resistance by the 12th SS Panzer Division “Hitlerjugend,” which itself had suffered heavy casualties in the defense of Caen. The 12th SS had deployed its antiaircraft batteries as field artillery, and its engineer battalion was fighting in the infantry role.

The 49th British Division’s advance on Rauray was stopped by the Germans, exposing the “Scottish Corridor” into which 15th Scottish advanced, exposed to counterattack. The British armor suffered heavy losses, as did the infantry from nests of machine guns and Nebelwerfers—multibarreled mortars. The advance ground to a halt on the Caen-Villers-Bocage road.

On the evening of June 27, the 2nd Battalion, Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders took the small Tourmauville bridge over the River Odon by slipping through a gap in the German defenses; they dug in and held on. The 11th Armoured was quickly up in support and across the bridge heading toward the Orne and open country. Lieutenant Pratt of C Squadron, 23rd Hussars, crossed the bridge half an hour after the Scots took it.

According to one historian, 11th Armoured’s Shermans “ground along in low gear up a steep and twisting track through wooded and difficult country until they came out just south of the village of Tourmauville (south of the river) where, for the first time, they were able to fan out on ground that gave a good field of fire. Commanders and gunners strained their dust-filled eyes. Were some of those bushes camouflaged tanks?”

On June 28, B Squadron of the 23rd Hussars, 11th Armoured Division reached the top of Hill 112. A counterattack by elements of the 12th SS Panzer with Panther and Mark IV tanks, was beaten off but not before several Shermans were knocked out as the intensity of the German attacks increased. By then some 40 British tanks had been lost; however, the infantry and tanks had now been joined by the supporting arms, but their position on Hill 112 was tenuous, being surrounded on three sides and at the end of a long, exposed corridor.

Pressure had risen behind them farther back on the corridor between June 26-July 1. General Paul Hausser of II Panzer Corps launched the 9th, 10th, and part of the 2nd SS Panzer Divisions against the western flank of the corridor. The Germans were driven back by VIII Corps with the help of close air support by rocket-firing Hawker Typhoons. The British also had the advantage of Ultra decrypts warning them of the impending attack.

General Hausser reported, “Murderous fire from naval guns in the [English] Channel and the terrible British artillery destroyed the bulk of our attacking forces in their assembly area. The few tanks that did go forward were easily stopped by British antitank guns.”

Midshipman Tony Robinson of the battleship HMS Rodney went ashore with the Guards Brigade and saw evidence of the effect of the naval gunfire from 15- and 16-inch guns. Near Tilly, they came across a Tiger tank and Robinson recalled, “The turret had been wrenched from the body of the tank and lay in the grass some distance away.” Nearby he noticed the graves of the crew.

Lieutenant General Sir Miles Dempsey, commander of the British Second Army, felt Hausser’s Panthers would launch another attack, so he ordered 11th Armoured to withdraw to the west bank of the Odon, thus retiring from Hill 112 with the approval of Montgomery, who wrote, “In view of this, it was decided that VIII Corps should concentrate for the time being on holding the ground won, and regrouping started with the object of withdrawing the armour into reserve ready for new thrusts.”

Hausser’s SS panzer divisions did not renew their attack until late on June 30 and July 1, but by then the opportunity to cut the British off in the corridor had passed.

Thus Operation Epsom came to an end; the value of Hill 112 had not been appreciated at the time, nor the ineffective nature of the German counterattacks. In the month to come this would cost the troops who would fight for Hill 112 dearly during a new operation called Jupiter.

At the end of June 1944, Montgomery reviewed the situation. He felt he had been successful in that forcing the “enemy to place the bulk of his strength in front of the Second Army, we have made easier the acquisition of territory on the western [U.S.] flank.” Second Army now faced eight identified German panzer divisions, whereas there were only two on the American front.

Monty told his Army commanders, Dempsey and General Omar Bradley of the First U.S. Army, that they had to “retain the initiative” and “on no account must we remain inactive.” Thus the Second British Army’s main task was to hold the enemy in the Villers-Bocage area. Therefore, to keep the “pot boiling,” the reinforced 43rd Wessex Division would attack Hill 112.

Days before Maj. Gen. Gwilym Thomas’s 43rd Wessex Division attacked Hill 112 in an attempt to break out to the west, the Germans had wanted to relieve II SS Panzer Corps from its defensive role with infantry divisions. However, by the time of the attack on July 10, the key feature of Hill 112 was still held by the 10th SS Panzer Division “Frundsberg” with the 21st Panzergrenadier Regiment while 22nd Panzergrenadiers held the gap between the eastern edge of the hill and the Orne River. In support were the guns of the II SS Panzer Corps. The well dug-in SS soldiers with armored support would be a formidable foe for the 43rd Wessex to dislodge.

At dawn on July 10, the British opened the battle with a 15-minute bombardment by more than 1,000 guns, aided by cruisers, monitors, and battleships whose guns ranged from 6-inch to the 16-inch guns of HMS Rodney.At 5 AMthe bombardment reached its climax, and four infantry battalions of the 130th Brigade rose from their start line and advanced toward the left flank of Hill 112. Moving through fields of tall wheat, they saw their objective, clearly marked by the dust of the bombardment above the hill.

With the 5th Dorsets leading the advance, the Les Duanes farm quickly fell, its defenders still stunned by the ferocious barrage. At Horseshoe Wood, the Germans, with more time to recover, put up stiff resistance. Lt. Col. Coad recalled, ‘Winkling out the loathsome SS with rifle butt, bullet, and bayonet had been a costly affair.’

By 8 AM, the leading units had reached Eterville, where 4th Dorsets dug in around the hamlet but then received orders to press on to the village of Maltot. They advanced in extended line through cornfields toward the village but came under heavy machine-gun fire and the shells from Tiger tanks in hull-down positions. Corporal Chris Portway, a section commander, recalled, “They knocked us down in lines.” Reaching the village, the 4th Dorsets fought from house to house.

Unknown to Portway and his section, the order to withdraw had been given, and his men came under heavy fire from the British covering artillery. There he was captured—an event that left him stunned. “I couldn’t believe that I’d never see the unit again,” he said.

The 9th Royal Tank Regiment in open country beyond Eterville was covering the open flanks with its Churchills, heavily armored tanks but with poor 75mm guns that were no match for the German tanks. However, in support was an antitank regiment that had M10 tank destroyers mounting the excellent 17-pounder gun—the best Allied gun. But these vehicles were poorly armored and, even worse, had an open turret that proved to be a huge disadvantage as the crew could be knocked out by air bursts or even a well-placed mortar shell.

The 129th Brigade, unlike the 130th, had no villages to take. It was to advance on a wider front, its objective being the slopes of Hill 112. It was supported by the tanks of two squadrons from the 7th Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment (7/RTR) and Crocodiles—Churchill tanks equipped with flamethrowers—of 79th Armoured Division.

However, things began going wrong before the start. Captain D.I.M. Robbins of B Company, 4th Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment recalled, “We lined up in the open in the FUP [forming-up point] and over zoomed the artillery. It was very noisy and quite exciting.

“Suddenly some heavier artillery started coming whistling towards us like a train. I thought that this was unusual and that it may land near us, and it surely did. It was our 5.5-inch medium guns dropping short. They wrote off our leading platoon. I remember men from 11 Platoon lying all over the place and one chap being carted off with no legs. The company commander said, ‘We can’t go into battle with the SS like this.’

“The CO, Ted Luce, came up and said, ‘What’s left?’ and I remember saying, ‘Ten men from that platoon and a few from this.’ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘Form up, we haven’t much time. We are going over.’ At 0500 that depleted company went over.”

From the high position of his halftrack, Major John Duke of the 224th Battery, 94th Field Regiment watched the advance through the fields of standing corn. “We quickly ran into heavy mortar fire,” he said, “and found many wounded men crawling around in the standing corn and dead German SS antitank gunners lying around their guns.

“Bombardier Nobbs was soon able to report to Regimental HQ on his wireless that we had reached the first objective and Gunner Cox got a German Spandau [MG-42] and opened fire on some enemy infantry who appeared over the hill.”

Shortly thereafter, Major Duke was wounded by fire from a group of Tiger tanks that had just arrived on the battlefield; the Wiltshire’s antitank guns engaged the Tigers, stopping one tank. A standoff developed between the Wiltshire Battalion and 21st SS grenadiers with the Tigers in support. The Germans were held back by the 17-pounder antitank guns that took advantage of the standing corn to conceal their positions. But the Churchills of 7/RTR were caught in the open, and four tanks were destroyed by the Tigers.

The 4th Battalion, Somerset Regiment went into the assault on the right of the Wiltshires but had the advantage of much of their approach being through dead ground. However, from their start line they were in open view. A creeping barrage helped keep the Germans’ heads down, but casualties in men and armor soon mounted. With the appearance of German Mark IV tanks on the crest, the panzergrenadiers counterattacked.

The Somersets were brought to a halt on the Caen-Evrecy road, unable to make further headway no matter the goading from Brigade HQ. Lieutenant Sydney Jarry of the Somersets described the British problems: “When we attacked a German position, the problem, though a simple one, was very difficult to overcome. Vastly superior infantry firepower, both small arms and antitank, was their trump card. A German infantry platoon could produce about five times our firepower. There was no way through the curtain of fire from the MG-42s. Sometimes, by stealth, we were able to bypass it; otherwise artillery or armoured support was necessary—often both. But due to their excellent anti-tank guns … the use of armour could prove costly.”

The 5th Wiltshire Battalion went to the right of the Somersets, the last in line of 129th Brigade. This unit had been in the line since June 29 and thus through its reconnaissance patrols knew the ground well. Their mission was to clear the Caen-Evrecy road and provide a flank guard to the southwest to protect the rest of the brigade once Hill 112 had been secured.

On their front, the British bombardment stunned the SS defenders. The 5th Wiltshires reached their objective relatively quickly but soon came under heavy shell and mortar fire, so they hastily dug in. C Company went farther forward to clear the enemy along the crest of the hill but quickly became pinned down by heavy fire; it was not until 5 PMthat they could be extricated—a task that took much of 129th Brigade to achieve.

With 129th Brigade’s assault stopped, 130th Brigade sent the 7th Hampshire Battalion forward to their objective: Maltot and the woods south of the village. Once Maltot fell, the plan was for the 4th Armoured Brigade to advance to the Orne and cross the river into open country. However, this depended on 129th Brigade holding the dominant feature of Hill 112, which they had failed to do.

The 7th Hampshires were reinforced on their right by two companies of the 5th Dorsets; in support was A Squadron, 9/RTR. The attack penetrated deep into the enemy positions but was subjected to a crossfire from Hill 112 and Maltot, the village being hurriedly supported by four German Tiger tanks that had arrived at the same time as the Hampshires.

Willi Fey, commanding the leading Tiger, said, “We reached the edge of the village. Wasting no time, we pushed through the hedges. There in front of us were four Sherman tanks. Panzers halt. On the left hand, tank 200 meters. Fire at will. Two rounds finished that one on the left; the one on the right suffered a similar fate, and our platoon commander pushed forward to knock out a third. The fourth sought safety by rushing back along the road.” (Newly arrived from the Russian front, the German unit’s ability to recognize Allied tanks was not their strong point; these tanks were Churchills, not Shermans.)

The 7th Hampshires reported to 130th Brigade HQ that they had occupied Maltot. However, this was not the case as many of the buildings were still defended by the Germans. The Dorsets west of the village were driven back. By midday the report had changed—the situation was now in the balance. The 9/RTR was buckling under the pressure, A Squadron having lost 75 percent of its tanks.

By 1 PMa stalemate had descended on the front. The Germans had contained the British advance but were exposed. It had taken a reinforced 10th SS Panzer Division to achieve this while the 9th SS Panzer Division was still some way off. The Germans were well aware of Montgomery’s tactics but had to respond to stop a British breakout.

Meanwhile, the 43rd Wessex had little in reserve to continue the attack other than the 4th Armoured Brigade, whose commander, Brigadier Michael Carver, was unwilling to commit his lightly armored Shermans to the battle; he feared that if he did the leading regiment would suffer 75 percent casualties.

At 3 PM the British commanders met at the Fontaine Etoupefour church. From its tower they could see much of the area, and it was obvious Hill 112 had not been taken. Elements of 4th Armoured Brigade were brought south of the Odon to protect the gains from German counterattacks; elements of three SS panzer divisions had been identified in the area. The 4th Dorsets were ordered up to support the Hampshires at Maltot, while the 5th Battalion, the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry (5/DCLI), would try to take Hill 112.

Captain Pat Spencer Moore, ADC to the 43rd Wessex Division’s commander, Maj. Gen. Gwilym Thomas, expressed his quandary: “It was clear to [Thomas] that only a completely fresh attack on Hill 112 could stabilise the battle, perhaps even win it, or perhaps incur even more shattering losses? It was a gamblers throw by Thomas … he was gambling with the lives of hundreds of his well-trained but completely green young soldiers. It must have been a terrible decision….”

Meanwhile, an attack by the 20th SS Panzergrenadiers on Maltot confirmed the need to support the 130th Brigade. Artillery slowed down the Germans, but it took rocket-firing Typhoons to halt the advance. However, they were not as effective against concealed targets and did little to help the 129th Brigade’s attempt to take Hill 112. Even so, the Hampshires were unable to hold onto Maltot; the 4th Dorsets approaching the village met the Hampshires withdrawing.

BBC reporter Chester Wilmot witnessed the scene: “By now that wood was enveloped in smoke … not the black smoke of hostile mortars but white smoke laid by our guns as a screen for our infantry who were being forced to withdraw. We could see them moving back through the waist-high corn, and out of the smoke behind them, came angry flashes as the German tanks fired from Maltot.

“But even as the infantry were driven back, another battalion was moving forward to relieve them, supported by Churchill tanks firing tracer over the heads of the advancing men. They moved right past our hedge out across the corn. The Germans evidently saw them coming, for away to our right flank machine guns opened up and then the Nebelwerfers.”

By 4:45 PM, the Dorsets had reached Maltot and were street fighting with the SS panzergrenadiers for possession of the shattered village. At 8:30 the 4th Dorsets were given permission to withdraw, but many were captured, not having received the order. Of the Dorset battalion that fought at Eterville and Maltot, only five officers and 80 men reassembled in Horseshoe Wood.

The attack of 5/DCLI late on July 10 was the last throw in Operation Jupiter. They had to cross 400 yards of open ground to reach the crest of Hill 112. A heavy bombardment would proceed the advance, and they would be supported by 7/RTR. At 8:30 PM, the DCLI stepped off, their objective the woods and orchards on the crest of Hill 112. As they went forward, every available gun supported them—even the antiaircraft Bofor guns. The 7/RTR was late arriving and went forward with A Company in support of the leading companies.

At 9 PM, the report reached the German command that British tanks had taken Hill 112 from the worn-out 3/21 Panzergrenadiers. Having gained the position, 5/DCLI dug in behind banks and hedges; they knew the inevitable counterattack would be coming.

It was dark by the time the SS infantry, supported by Tigers, attacked. The Cornish infantry stopped the grenadiers, and the Tigers were wary to go on alone, fearing the British PIATs (Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank—a hand-held antitank weapon) at close range. However, losses in the bigger 6- and 17-pounder British antitank guns mounted.

Another German attack came near midnight as B Company of DCLI had to abandon the forward hedge. Private John Mitchell described the desperate fighting: “My mate and I were digging in, in the second to last hedgerow from the crest. We both cried out in dismay as the hedge came down on top of us; a Panther most likely, was pivoted on the bank and we were underneath, with the tracks on either side of us. The large gun on the tank fired, it was deafening, so much so we hardly heard the shell hit the underbelly of the tank inches from us. It was a ‘PIAT’ fired by one of our lads at close range. The Panther backed off the bank as it was possibly damaged.”

As the night wore on, 5/DCLI’s strength ebbed away. Lt. Col. Dick Jones, a 26-year-old prewar Territorial soldier, had only been in command of the battalion for two weeks, but he displayed exemplary leadership. At dawn on July 11, the DCLI was still holding on, having repulsed numerous attacks throughout the night. They received word that a company of the 1st Worcester Battalion and a squadron of the Scots Greys from 4th Armoured Brigade were to support them; however, the lightly armored Shermans were no match for the German tanks. In a short time the Scots Greys were reduced to four tanks after they had attracted the fire of 9th SS Panzer, which had occupied the southern slopes of Hill 112.

The 3rd Battalion, 9th SS Panzergrenadiers launched a fresh attack in broad daylight. Control for them was better, but it also gave the British the advantage of using their artillery. Colonel Jones himself climbed a tree from which he had a clear view of the Germans; he called down map references to a signaler, Private Jack Foster, to relay to the batteries. He was no doubt glad to see the enemy withdrawing under the heavy, accurate fire. However, he was spotted and a burst of fire killed the heroic colonel.

At about 3 PM, the SS mounted another attack. A Major Fry, the sole surviving officer, now gave the order to withdraw; 5/DCLI had been in action for 21 hours. It had been “a battle of shattering intensity even by the standards of Normandy,” as one historian wrote. Others compared the bombardments to those suffered at Passchendaele during World War I.

Hill 112 had not been held by the British, nor had the Orne crossing been seized, but they had not been the real objective. Rather, four SS panzer divisions had been drawn into a defensive battle and worn down to such an extent that II SS Panzer Corps would never again reach the level of strength it had on July 10, 1944.

Montgomery came in for some criticism for his handling of the Normandy campaign. Patton commented, “Montgomery went to great lengths explaining why the British had done nothing.” Eisenhower, under pressure from Washington, wrote, ‘It appears to me that we must use all possible energy in a determined effort to prevent the risk of a stalemate.”

Montgomery was certainly not the easiest man to get on with and not always right, but history, the great arbitrator, has come to see Operation Jupiter not as a tactical success for the 43rd Wessex Division, but rather a strategic success for Montgomery.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments