By Mark Carlson

The final defeat of the Saxon King Harold at the Battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066, meant that England became forever Norman. The driving force for the transformation of this island nation was personified in William, Duke of Normandy—William the Conqueror.

The Norman Conquest involved more than the usual reasons of national interests or the desire for land and resources. This was personal, driven by pride, revenge, greed, audacity, and extraordinary luck. While the battle is well documented, there are still gaps in accounts of the invasion itself. How, in only a few months, did William assemble a huge army of 8,000 infantry and cavalry and build a fleet capable of carrying them across the stormy English Channel? Nearly a thousand years later it remains the most compelling element of the Norman Conquest.

In 1064 England was ruled by 60-year-old King Edward the Confessor. The Earl of Wessex, Harold, Son of Godwin and brother of the Queen served as Edward’s regulator in the kingdom. In this role he was considered heir to the throne. That summer he embarked on a hunting expedition along the coast, but his ship was caught in a severe storm that drove him onto the rocks on the Normandy coast. The region was under the absolute control of William, Duke of Normandy. Normandy was a land of Norse descendants who had a warlike tradition. At age seven, William was named the Second Duke after his father died during one of the early Crusades. Until he reached the age of 15, he was under constant threat of assassination by the ambitious and combative Barons and nobles. As an adult, William proved to be a barbarous and powerful leader with no scruples except his staunch loyalty to the Catholic Church.

While William’s father, Robert, had been the Duke of Normandy, his mother was the daughter of a common tanner—making him a bastard. Anyone who sneered at his illegitimacy was skinned alive.

William was ambitious, and had convinced himself that Edward had promised the throne of England to him during a visit there in 1051. This is unlikely, since Edward was well aware that he had no power under the English Constitution to promise the kingdom without the approval of the Wittens, the Saxon council.

Then Harold was brought before William in Rouen. According to Norman accounts, Harold swore on holy relics that upon Edward’s death, he would concede the crown to William.

Whether he did this willingly or under duress is not known, but William was certain Harold would keep his word. Harold was known to be a fair and honorable man.

But when King Edward died in January 1066, the man who claimed the throne was not William, but the 40-year old Harold Godwinson. By breaking his sacred pledge to William, Harold had created an implacable and mortal enemy.

Not only did William feel cheated of the crown he had been promised, but he had been made a fool in the eyes of the English—intolerable to a man so proud and ambitious. He began planning what would be the most daring and challenging invasion in history.

The task was formidable. First, William needed to form an army of infantry and cavalry, in itself no small task. Then he had to build a fleet of ships to carry the army across the stormy Channel to land on hostile shores—all before the coming of winter.

But the 38-year-old Duke was probably the only man on Earth who was both audacious enough and capable of achieving the impossible. William was initially unsuccessful at raising the support of the Norman nobles for his invasion.

Historian David Howarth claims in his book 1066: The Year of the Conquest, that William’s “outraged pride gave them too much assurance and not enough persuasion.” It was generally known that the English could mass a large fleet and at 10,000 men-at-arms. But William declared “Wars are not won by numbers, but by courage.”

He convinced them that Harold had sworn on holy relics to give him the crown. Then he used two very powerful incentives, greed and the church. An invasion of England would mean great riches for the barons who supported him, but his greatest coup was in convincing Pope Alexander II, himself an ardent supporter of the first crusades, of the rightness of his claim. Receiving Papal blessing for his holy crusade was his most potent weapon in the war to come.

The Regent of France, Count Baldwin, provided French cavaliers and their horses, while his representatives scoured Brittany, Flanders, Burgundy, Aquitaine, and Poitou for veteran foot and mounted men-at-arms.

As for the ships he needed for the channel crossing, William’s half-brother Bishop Odo promised 100 ships while another half-brother, the Count of Mortain, pledged 120 more. The nobles of Montgomery and Eu offered 30 each.

Soon the number rose to more than 800, but actually obtaining and building them was a far greater challenge. They recruited thousands of woodcutters, carpenters, blacksmiths, and teamsters to cut and transport the timber for the fleet. While the nobles bought, begged, borrowed and probably stole every craft capable of carrying men or supplies to England, the woodcutters and carpenters began to build.

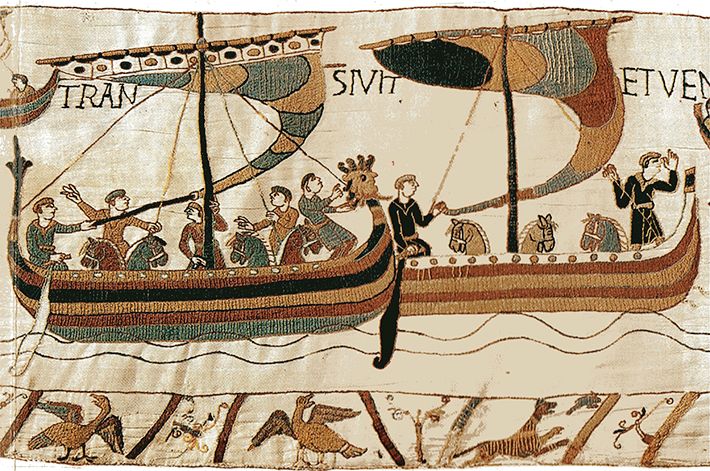

William’s armada was a fleet in name only. Very few of the vessels were of a single type. They ranged from small wide-hulled fishing smacks of 20 feet with a crew of four, while others were 50 or more feet long. While the largest were modeled on the classic Viking longships, others were purely for carrying goods and cargo. One thing they all had in common was their basic construction.

They were clinker-built with high stems and sterns, graceful with shallow draft. They could be elaborate with beautiful carvings or slapped together with no embellishment. According to Howarth, they “were economical in labor, but extremely wasteful of timber.”

How many ships William had under his command is not known, but historical estimates range from 696 to several thousand. The lower figure is more likely. But even this would have needed at least 12,000-15,000 full-grown trees. The Duke had an army of 4,000 infantry, 1,000 archers and 3,000 cavalry. With the larger ships carrying 60 men and 10 horses, at least 300 would have been needed for the horses alone.

In a remarkably short time, by early August, the work was largely complete.

The Normandy coastline extended from the Cotentin Peninsula, east past the Seine and Dives Rivers, a distance of 165 miles. There were few sheltered harbors and strong tides. During the summer the winds were nearly always out of the north or southeast. William needed southwest winds to carry his fleet to the shores of England. The army and fleet assembled at the mouth of the River Dives just east of Caen and 100 miles from Beachy Head, his intended landing area.

It would take a day to load the ships and, with a speed of about five knots, he needed a full night of steady winds. Every day Duke William prayed in the Norman chapel and watched the weathervane on the tower. On August 12, the winds seemed favorable and William had the ships loaded. Food and weapons, armor and arrows, barrels of wine and sacks of dried meat and grain, all the impedimenta of medieval war were loaded as fast as possible.

Pre-cut timbers were loaded for constructing a fort at the landing site. When the horses and their riders at last took their places on the ships, William sent the word to sail north out of the mouth of the river and head for England.

But the first attempt at a crossing was ended when winds from the north forced them to seek shelter at Saint Valery at the mouth of the Somme 60 miles from the English coast. While this was fortuitous, William was no longer in his own land. Even more frustrating was that he was trapped and unable to leave as long as the winds remained from the north.

Another month passed as the discouraged army remained encamped along the river estuary. Time was running out for the Duke. He was certain Harold was aware of the impending invasion and assembling an army.

He was right. After convincing the earls of Sussex, Hull, Wight and Dover of the danger, King Harold assembled an army of about 8,000 foot soldiers. They were the earls’ professional Housecarls and militia Fyrds armed with axes, swords, spears, clubs, helmets, chain mail and leather armor. The army was contracted for two months of service, meaning that if no invasion materialized, they could go home in mid-August.

The square sails in use across northern Europe meant that ships were limited to sailing mostly downwind. Southwest winds on the Channel would force the Normans to land somewhere east of the Isle of Wight.

Assuming William would arrive on English shores in the early summer, Harold used his fleet of 400 boats and ships to carry the majority of the army to the south shore of the Isle of Wight and east to Hyde, Hastings, Beachy Head and Pevensey. Harold’s own vessels were light and easy to row. With most of them pulled up on shore and a few remaining in the water for rapid use, the army watched and waited. It only took one man to raise the alarm while the others called in the troops.

Harold never intended to use his fleet to intercept William at sea and fight him there. The Norman and English ships were only intended to move troops, and in William’s case, horses. King Harold waited in Bosham in Chichester where he had been raised. The town was on a peninsula only 60 miles from London.

As summer dragged on with no invasion in sight, his troops became bored and impatient to return to their homes. Though their period of enlistment had ended on August 14, they remained longer. But by early September, it appeared that Harold had been wrong.

Harold’s plan had been to pinpoint the landing site, then send the army at the Isle of Wight east by sea to cut off and destroy the invading fleet while his land troops cut off the Norman advance. It was a sound plan, but as history has often proven, no plan survives first contact.

In what has to be the most extraordinary coincidence in history, another invading fleet was landing on England’s shores 200 miles north of London. The invaders were the Vikings under King Hardrada of Norway. Harold’s exiled brother, the mentally unstable and devious Tostig Godwinson had recruited the Vikings to invade so he could overthrow Harold and claim the crown.

Hardrada’s men were always ready to attack and invade England, and were, even more important, experienced seamen. They had a ready fleet of 300 longships and an army of battle-hardened warriors. After two days’ sailing across the North Sea the Vikings landed at the mouth of the River Tyne in Northumbria.

The date was September 9, the day after Harold’s troops began returning home, convinced there was no chance the Normans could invade before the Vernal Equinox and the end of summer. On that very day Duke William was contemplating his disgrace, knowing that if the winds did not shift into the north he would have to disband his army and abandon the fleet.

King Hardrada’s bloodthirsty warriors stormed into Scarborough and began burning, looting and killing.

King Harold was back in London when he heard of the Viking invasion and hastily assembled an army of 6,000 men and marched north to fight the invaders. After a savage battle at Stamford Bridge on September 25, both Hardrada and Tostig were dead. The Norsemen had been decimated, with less than a tenth surviving to limp back to Norway.

On the evening of September 26, William saw the banners over his ships flutter. The wind was hard and steady right out of the south. God had at last heard his prayers. He ordered the ships loaded and prepared to move out. William and his staff, which included his half-brothers Bishop Odo and Robert of Mortain, climbed onto the deck of his flagship Mora.

It was late afternoon on the 27th when Mora’s sail was unfurled and it slid north out of the Somme estuary. “The Duke sent a herald to the other ships to wait until they saw the lantern at his masthead in the night. They were to make sail and follow,” Howarth wrote. The invasion fleet was on its way.

At an average speed of five knots, it would take about 12 hours to cross the 60 miles of open sea. The night was bitterly cold and the soldiers, not being accustomed to boats, were nervous but eager. The months of work and waiting were over.

Their objective was a sheltered harbor and sufficient beach to land on, as well as a route inland. William was aiming for Hastings. But navigating blindly across the Channel at night while staying close together was not an easy task. Mora’s pilot had to find a known landmark and use it to guide him while the other ships would follow.

Hours passed with the sound of water under the hulls, flapping sails and the murmur of voices.

When the early dawn erased the stars to the east, there was no sign of the white cliffs of Dover. Even worse, Mora was alone. The Duke ordered the sail lowered and, concealing his frustration, ate breakfast.

As the fastest ship in the fleet Mora had simply outdistanced the others, especially the heavilyloaded cavalry transports. As the sky grew lighter, acres of sail appeared to the south and the fleet rejoined Mora.

Beachy Head was sighted and the fleet headed in, making landfall at Pevensey at about 9 a.m. A Roman fort dominated the harbor, but no English soldiers were waiting. The cavalry jumped into the shallow water and moved ashore, the first Normans to invade England. William had done the impossible.

As Harold and his tired but victorious men marched south, a courier arrived with the portentous news that his mortal enemy, Duke William of Normandy, had landed his army. At that moment Harold must have begun to doubt that God had anointed his reign. With no other choice, he urged his men forward and sent out a call for more troops.

The Duke led his 8,000 archers, soldiers and cavalry into Sussex, arriving at Hastings a day before Harold. It was Friday October 13, 1066. Hastings was a narrow valley between two hills, Caldbec and Telham. King Harold’s army of 8,000 Housecarls and Fyrd militia took positions on Senlac Ridge. Tired but angry at the invasion, his troops were ready to fight. But the Duke of Normandy had a great advantage: heavy cavalry, archers and the blessing of the Pope. William had no doubt that God was with him and the usurper of his legitimate claim to the throne had no chance. The following day the armies of King Harold and Duke William met for the fateful battle that would change history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments