By Henrik O. Lunde

In 1941, Finland joined Nazi Germany in its attack on the Soviet Union, resulting in the third war with its giant eastern neighbor in 23 years.

Democratic Finland had two reasons for aligning itself with totalitarian Germany. First and foremost, Finland wanted to recover the territories lost in the 31/2- month Winter War against the Soviets, November 1939-March 1940. Second, the Finns wanted to conquer East Karelia. The Karelians were linguistically and culturally related to the Finns but East Karelia had never belonged to Finland.

The anomalous coalition between a democracy and a dictatorship presented numerous problems, but the most serious resulted from the failure of the two countries to orchestrate their war aims and to develop plans for its prosecution beyond the opening phase.

The spectacular initial German victories in World War II had led everyone to believe that the war would be short, that long-term planning was unnecessary. The anticipation of a quick victory at the side of Germany appears to have blinded the Finns to the obvious implications of a failure by Germany to achieve its war aims. Such a failure meant that Finland had to count on a day of reckoning with the Soviet Union.

In 1941, Finland, in a large and well-executed offensive, quickly recovered its lost territories and went on to conquer most of East Karelia. The Finns then adopted a defensive posture for 21/2 years and repeatedly refused to assist the Germans in their attack on Leningrad. The Germans had brought an army from Germany and Norway to central and northern Finland for the purpose of capturing Murmansk or severing its rail connection to the rest of the Soviet Union. This was vital in stopping the flow of Lend-Lease supplies to their common enemy, the Soviets. However, the Finns, largely because of pressure from the United States (which still maintained diplomatic relations with the Finns), declined to assist the Germans in this venture. The war in Finland then stabilized into trench warfare with little activity on either side.

Popular support for the war in Finland dropped dramatically when, after the Soviet victory at Stalingrad, the war turned decisively against the Germans and the Finns realized that the conflict would not turn out as they had anticipated. The Finns began tp put out serious peace feelers through third parties in 1943, but the last Soviet offer was found unacceptable by the Finns in April 1944. The stage was set for renewed conflict.

When they met at Tehran in December 1943, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin had agreed to coordinated offensives against Germany in the summer of 1944. In view of that agreement, it is important to understand why the Soviets launched a massive offensive in a secondary theater against Finland in June 1944. This article does not address Soviet offensives in East Karelia but focuses exclusively on their offensive on the Karelian Isthmus and the final Finnish stand at the so-called VKT Line.

Russia’s Campaign to Settle the Finnish Question

There were at least two reasons for the Soviet decision and the timing of the offensive against Finland. First, Stalin was still skeptical about the planned American/British landing in France. Spending some time dealing with Finland after the landing would give him a chance to see how the operation in France developed before beginning the planned large-scale offensive against the Central Army Group in Byelorussia.

Probably more important was Stalin’s strong desire to have the Finnish question decided without Western interference. Finland still enjoyed considerable sympathy in the West and Stalin wanted to settle things with Finland alone and not let it become part of the wider settlement of issues after the war.

The Soviets began planning an offensive against Finland as soon as Finland rejected their peace offer in April 1944. The objective was rather simple. The Finnish Army was to be destroyed, forcing Finland to capitulate. To achieve this, Stalin demanded that the attack be exceptionally violent and quick.

General Leonid Aleksandrovich Govorod, commander of Soviet forces on the Karelian Isthmus, was given two armies––the Twenty-first and Twenty-third (later also the Fifty-ninth)––consisting of seven corps. The Soviets expected to defeat the Finnish forces on the isthmus and capture Viipuri, the capital of Karelia, within 12 days. They would then press on north and west and have the capital of the country in their hands by the middle of July.

General Krill Meretskov, who was responsible for operations in East Karelia, also had two armies at his disposal––the Thirty-second and Seventh. The East Karelian offensive was planned to begin around June 20, 1944, its mission to trap the Finnish forces in that area and keep them from interfering with the operation on the Karelian Isthmus.

Some of the troops allocated against Finland were needed in the offensive the Soviets planned against German Army Group Center in Byelorussia starting on June 22. Soviet planners felt confident that they could achieve their objectives in Finland before the start of that offensive. The troops had trained and prepared for their missions for several weeks.

The Finnish Army’s Deficient Defensive Posture

The strength of the Finnish Army in June 1944 was about 450,000 men. However, less than one-third of the army was located along the most likely Soviet avenue of approach on the Karelian Isthmus. Large forces were stationed in East Karelia along the Svir River and in the Maaselkae sector north of Lake Ladoga.

The poor positioning of Finnish forces for dealing with an offensive along the most likely avenue of approach and the unsatisfactory condition of defensive positions are some of the most hotly debated issues in Finnish military history. While some strengthening of the forces on the Karelian Isthmus had taken place in the spring of 1944, and the construction of fortifications speeded up, it was too little and too late.

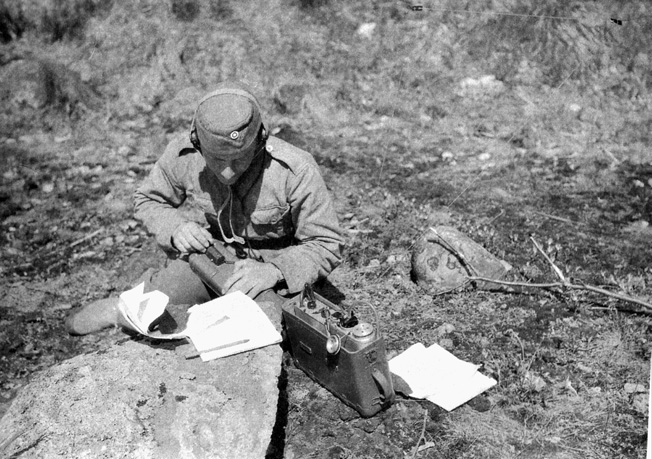

The long period in a static defensive posture and rumors of peace initiatives may have led to a lowering of morale and a loss of the fighting élan so evident in the Finnish Army in the 1941 offensive. The troops and their leaders appear to have become somewhat complacent. This is reflected in the lack of vigorous training, a lack of urgency in the construction of fortifications, and a slackening in aggressive intelligence gathering.

The defense of the Karelian Isthmus was based on three defensive lines. The first represented the front occupied by the Finns on June 9, 1944, and it coincided roughly with the 1939 border. The second line, referred to as the VT (Vammelsuu-Taipale) Line was 14 to 30 kilometers behind the front. The third line (VKT Line) ran roughly from Viipuri to Kuparsaari and then along the Vuoksi River to Taipale. Construction of defensive positions on this line were not begun until six months before the Soviet offensive and was far from complete.

There were also several serious deficiencies in armaments, particularly for defense against enemy armor. The lighter Finnish antitank weapons were ineffective against modern Soviet heavy tanks, and the heavier ones were difficult to move around on the battlefield. More suitable German infantry antitank weapons were requested on a rush basis only after the start of the Soviet offensive.

The Finns believed that a Soviet offensive against Finland would not take place because the Soviet objectives would be achieved with the defeat of Germany. This view may have caused the Finns to keep the bulk of their forces in East Karelia, possibly hoping its possession would give Finland a bargaining chip in the settlement following a German defeat.

This outlook may have influenced Finnish failure to heed repeated intelligence warnings. On June 1, 1944, the Finnish intelligence service warned the general staff that a Soviet offensive should be expected within 10 days. The Soviets also launched company-size probing attacks and imposed radio silence on their forces four or five days before the offensive––sure signs that something big was afoot.

But the Finnish general staff was not convinced and no steps were taken to bring in reinforcements from East Karelia. As historian Olli Vehviläinen correctly notes, the “highly motorized Red Army hungry for victory was met by an army ill prepared in both morale and equipment for confrontation on the massive scale that was being fought in 1944.”

“The Black Day of Our War History”

The stillness of the Karelian Isthmus was shattered on June 9, 1944, by a fury that is hard to imagine. Over 1,000 Soviet aircraft carried out saturation bombing of the Finnish front line; it was accompanied by a massive artillery preparation and followed by a ground assault at 5 am on June 10––a day that Marshal Gustav Mannerheim described as “the black day of our war history.”

The Soviets threw two armies––the Twenty-first and Twenty-third––against the Finnish line on the Karelian Isthmus, which was held only by two corps (IV and III). The main thrust was directed at the 10th Finnish Infantry Division holding the right flank of the Finnish IV Corps along the Gulf of Finland.

The Karelian Isthmus front was only 70 kilometers wide and, in this relatively narrow sector, the Soviets employed 270,000 troops, 1,660 pieces of artillery, 620 tanks, and 1,500 aircraft. The quantitative advantages enjoyed by the Soviets on the Karelian Isthmus were overwhelming: troops 4:1, armor 5:1, artillery 6:1, and aircraft 15:1.

As they had done so often against the Germans, the Soviets concentrated their offensive on a narrow front to achieve a quick breakthrough and then exploited that breakthrough with a pursuit by several corps operating abreast. The quantitative advantages at the point of main effort were therefore vastly larger.

The preparatory fires were exceedingly violent. It was the heaviest of the war, surpassed only by the storm unleashed in the Soviet crossing of the Oder River in their final drive on Berlin in 1945. It is reported that the Soviets deployed 200 to 400 pieces of artillery for each kilometer of front. The 13-14-kilometer-wide front of the 10th Finnish Division was hit by 220,000 artillery shells within a couple of hours and the 17-kilometer-wide front of the 2nd Finnish Division was smashed by 60,000 shells.

Pulverizing the Finnish 10th Division

The main effort of the 21st Soviet Army against the Finnish 10th Division had predictable results. The pulverizing effect of the Soviet fire destroyed the Finnish front-line trenches. The avalanche of exploding shells buried soldiers under tons of sand, earth, and debris. Protective minefields and barbed-wire entanglements were destroyed. Units lost contact with their headquarters as the rain of high-explosive shells severed telephone lines; radios were virtually useless due to the incredible noise created by the continuous explosions. Mannerheim writes that the noise from the battlefield could be heard both in Mikkeli––the location of his headquarters––and in Helsinki, respectively 220 and 260 kilometers from the battlefield.

The hell-on-earth situation in which the Finnish soldiers found themselves had a paralyzing effect. The debris and smoke from thousands of exploding shells reduced visibility to only a few meters. The losses were heavy and rising. Panic developed in many areas, and when the Soviet infantry reached the Finnish trenches, they sometimes found them empty except for dead and wounded.

The weight of the Soviet attack by three corps (109th, 30th, and 97th) fell on the Finnish 10th Division and particularly on the regiment at Valkesaari, commanded by Colonel Viljanen. The regiment was annihilated in the massive assault by three Soviet divisions, and a steady stream of enemy tanks and artillery batteries pushed through the breach. By midnight on the first day of the offensive, the Soviet Twenty-first Army had penetrated the IV Finnish Corps sector to a depth of 30 kilometers and widened the salient to an equal distance.

Reinforcing the Defensive Lines

Mannerheim and his staff realized the magnitude of the Soviet offensive on June 11. The 3rd Infantry Brigade and the 4th Infantry Division were ordered to the Karelian Isthmus. Mannerheim also requested German support in the form of ammunition, air support, assault guns, antiaircraft artillery, light infantry antitank weapons, and aircraft for the Finnish air force.

Lieutenant General Erik Heinrichs, chief of the Finnish General Staff, told General Eduard Dietl, the commander of German forces in Finland (20th Mountain Army), that plans were to give up the Svir and Maalekae fronts if the VT Line could not be held. This would make two or three divisions available to bolster the VKT line. Dietl urged Heinrichs to carry out that plan quickly, but he considered it possible that, in their reluctance to give up East Karelia, the Finns would procrastinate so long that the withdrawal would be jeopardized. Dietl believed the Finns could hold out indefinitely in a shorter line and thereby spare the Germans a withdrawal to Norway.

A large stretch of the VT line was already under attack on the morning of June 12. Mannerheim ordered the transfer of the 17th Division and the 20th Brigade by rail from the Svir Front to the Karelian Isthmus. Even with these reinforcements it appeared doubtful that the Finns would be able to hold the VT Line in view of the avalanche of men and matériel the Soviets poured into their offensive.

Since more and more Finnish units were on their way to or had received orders to move (the 11th and 6th Divisions) to the Karelian Isthmus, Mannerheim decided to appoint a single commander of the Karelian Isthmus; Lt. Gen. Karl L. Oesch was brought from the Lake Onega area for that purpose.

The Pursuit of Peace

The situation grew critical again for the Finns on June 14 and 15. Full-scale Soviet attacks against the VT Line from Siiranmaki to Vammelsuu tore up the Finnish western front over a 13-kilometer stretch despite stubborn Finnish resistance.

The Finnish High Command was convinced by June 15 that they could not hold the VT Line because reinforcements from East Karelia had not yet arrived. Some thought was given to occupying the old Mannerheim Line from the 1941 Winter War rather than withdrawing directly to the VKT Line, but General Oesch recommended making a stiff fighting withdrawal directly to the VKT Line since he did not think there was sufficient time to occupy the Mannerheim Line, and because it was in poor condition. His recommendation was accepted.

The Finnish political leaders panicked when the VT Line was lost and were prepared to make peace quickly and on almost any terms. The presidency of Finland was offered to Mannerheim since he was viewed as acceptable to the Soviets and was the only person capable of keeping the country together after the expected harsh peace conditions. The civilian leaders also wanted to proceed with peace discussions with the Soviet Union. Mannerheim refused the presidency but agreed the country should seek peace. This was on June 15 when things looked rather gloomy for the Finns.

Withdrawal to the VKT Line

By the next day, the VT Line had been penetrated to a depth of over 10 kilometers and all hope of restoring the front was lost. The Finnish infantry had great difficulty coping with the Soviet tanks, and so the Finnish High Command made an emergency request for German light antitank weapons. This request was acted on immediately.

The enemy was obviously heading for Viipuri but the Finns had no forces available to stop them. The greatest Finnish worry was that the Soviets would, for the time being, bypass the city and head for the 27-kilometer-wide isthmus between the Bay of Viipuri and the Vuoksi River. The Soviets had a good chance of reaching that isthmus before the III and IV Corps were in place. Such an event could be decisive since it would prevent the occupation of the western part of the VKT Line.

With his army under continued heavy attacks, Mannerheim ordered a withdrawal to the VKT Line on June 16. He also ordered a fighting withdrawal from the forward positions in East Karelia to the vicinity of the 1940 border, thus freeing up more combat units.

Soviet attacks and Finnish retreats continued unabated on June 16 and 17, and the Finns slowly retired in the direction of the VKT Line.

Soviet pressure was strongest along the Gulf of Finland coast. Some of the early reinforcements from East Karelia were now arriving. The 4th Division was directed to the lake country between Viipuri and the Vuoksi River.

According to the Soviet plans, Lt. Gen. A. Tjerepanov’s Twenty-third Army initially had the mission of binding the Finnish forces in its sector while the Twenty-first and Twenty-third Armies conducted the main attack farther west. Later, these armies were to attack the Finnish III Corps and cross to the eastern bank of the Vuoksi River. Because of its more limited tasks in the offensive, the Twenty-third Army was assigned only two corps initially; plans were to add another corps as operations progressed.

The Twenty-third Army was faced with the III Finnish Corps, consisting of one division and one brigade, under Lt. Gen. Hjalmar Siilasvuo. Because its area of responsibility overlapped the sector of the Finnish IV Corps, Twenty-third Army also faced the Finnish 2nd Division belonging to that corps.

Since the VKT Line bent south along the Vuoksi River to Taipale, the III Corps did not have as far to withdraw as IV Corps. The fighting was nevertheless brutal and costly.

The VKT Line: Last Defensive Line on the Karelian Isthmus

With the expected arrival on the Karelian Isthmus of the 11th and 6th Divisions from East Karelia, the Finns had switched the preponderance of their forces from East Karelia to the Karelian Isthmus. The main elements of the 4th Division and the 3rd Brigade arrived on June 16. The 17th Division and the 20th Brigade arrived between June 18 and 20. The 17th Division was split: its 13th Regiment was assigned to the IV Corps and two battalions of that regiment took part in the fighting in the 4th Division sector. The rest of the 17th Division was moved to the Kilpeenjoki area as part of the strategic reserve.

To command the increasing number of Finnish forces on the Karelian Isthmus, the headquarters of Finnish V Corps under Maj. Gen. Antero Svensson was moved from the Svir front to the Viipuri area. On June 22, Svensson’s V Corps took over the reinforcements assembling in this area, including parts of the 17th Division, 20th Brigade, and a number of smaller units.

The VKT Line was the last defensive line on the Karelian Isthmus. The 20th Brigade was responsible for the defense of Viipuri on a five-kilometer-wide sector. It tied into the 3rd Brigade in the east, which also held a sector of approximately five kilometers. To its east was the 18th Division which held a 10-kilometer sector, followed by the 3rd Division which held the sector to the Vuoksi River where it tied into the 2nd Division of III Corps.

The reserve consisted of the Armor Division, the 10th Division, the Cavalry Brigade, and the 17th Division minus one regiment. These were all located near Viipuri. The 10th Division and the Cavalry Brigade had already been badly mauled and had lost most of their artillery and heavy equipment, while the 6th and 11th Divisions were still on their way to the Karelian Isthmus.

Govorov’s Promotion to Marshal

General Govorov, remembering the Mannerheim Line’s tenacious defense in the Winter War, had expected it to be heavily defended. Therefore, when Soviet forces reached this line and pushed through with virtually no opposition, they took it as an indication that the Finnish Army was finally destroyed. Govorov was quickly promoted to Marshal of the Soviet Union in anticipation of receiving a delegation of Finnish officers, who would acknowledge their defeat.

The Soviet advance continued and their troops soon reached Tali, northeast of Viipuri. Their order of battle was impressive: There were two corps in the vicinity of Viipuri and another six corps between Viipuri and the Vuoksi River. These corps contained 20 infantry divisions, three artillery divisions, four armored brigades, five to seven armored regiments, and seven self-propelled assault gun regiments. Against these, the best the Finns could hope for, by using all their reserves, was a force of ten divisions and four brigades.

Viipuri, the Karelian capital, fell quickly to the Soviets on June 20 after a short fight within the scheduled time frame laid down in Soviet plans. Had the Soviets bypassed Viipuri and directed their offensive a little farther east, against the narrows between Viipuri and Vuloksi, they could have frustrated Finnish efforts to establish themselves in the VKT Line, an area where they stopped the Soviet advance in 1940.

On the evening of June 21, General Oesch ordered Lt. Gen. Laatikainen to send elements of the 17th Division from Juustilla, north of Viipuri, to the northern coast of Viipuri Bay at Tienhaara to prevent the Soviets from crossing that bay; a crossing there would have outflanked the VKT Line from the west. These forces were in place in the afternoon of June 22.

German aircraft then carried out bombing attacks against the amphibious craft assembled by the Soviets on the other side of the bay. Following a heavy artillery barrage, troops from two Soviet divisions attacked across the bay in the evening of June 22. The attack was repelled but new attempts were made throughout the night and for the next three weeks.

Marshal Govorov decided that trying to cross the Bay of Viipuri would be too costly and time consuming. The Soviet troops involved were relieved by other forces and moved to the main operational theater in the Juustilla-Ihantala area.

Nazi Germany Aids the Finns

Despite having frustrated Soviet attempts to cross the Bay of Viipuri, things were far from bright for the Finns. Having captured Viipuri, the Soviets could direct their offensive both westward along the northern shore of the Gulf of Finland against the harbor city of Hamina and northward to Ihantala and Lake Saimaa from Lappeenranta to Imatra. After reaching these areas, the terrain opened up and the possibilities for an armor-led advance were excellent. The Finns knew that the decisive fight was close at hand.

Irritated by Finnish flirtations with their common enemies, in April 1944 Hitler had placed an embargo on military and food aid to the Finns. As soon as the magnitude of the Soviet summer offensive became evident, the Finnish military leadership realized that a catastrophe could only be averted with German help. The only other alternative was to seek peace with the Soviet Union. Both avenues were tried––simultaneously.

The two were actually linked, since the Finns had concluded that the only way to get acceptable terms from the Soviets was through stabilizing their fronts. In their desperate situation, the Finns were prepared to use German aid for purposes that were against the interests of their brothers-in-arms. Even if the Germans realized what the Finns were doing there was not much they could do about it except condition their aid, which was resumed as soon as the Soviet offensive began, on a firm commitment by the Finns to stay in the war. Not providing the requested aid would only lead to Finland being promptly knocked out of the war.

The Germans responded quickly to Finnish requests for assistance despite their own precarious situation. German torpedo boats brought in 9,000 shoulder-fired antitank weapons known as Panzerfauste (“tank-fist”). Mannerheim also requested a large number of the even deadlier Panzerschreck (“tank-terror”) weapons, as well as ground support aircraft. The Finnish request stated that the VKT Line could be held only if these requests were approved and delivery expedited. Five-thousand Panzerschrecks were airlifted to Finland on June 22.

General Heinrichs asked General Waldemar Erfurth, chief of the German liaison staff in Finland, late on June 19 if the Germans were prepared to provide aid other than weapons. He specifically asked for six divisions to take over the front in East Karelia so the Finns could concentrate their efforts on the Karelian Isthmus. The formal request was made by Mannerheim on June 20.

The German answer came quickly: It was impossible to provide the six divisions Mannerheim requested but other help was promised. This was a sensible answer in view of Germany’s own force requirements at the time. However, setting these aside, it made little military sense to send a large German force to East Karelia. The Germans already had their strongest army tied up in central and northern Finland, contributing virtually nothing to the war effort. It would be folly to send an equally strong force to be isolated in East Karelia where there would also be great difficulties keeping it supplied.

The German High Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht––OKW) promised significant help as long as they were assured that the Finns were determined to hold the VKT Line. Besides weapons, ammunition, and supplies, the Germans offered the 122nd Infantry Division from Army Group North and the 303rd Assault Gun Brigade.

OKW also agreed to make Luftwaffe units available. Air Group Kuhlmey (named for its commander, Kurt Kuhlmey), consisting of fighters and Stuka ground-support aircraft, were quickly flown to Finland. These 70 aircraft were stationed at Imola Airfield outside Helsinki. The air support was immediate and German aircraft flew 940 sorties in support of the Finnish Army on June 21.

This was substantial aid considering the desperate situation in which the Germans found themselves in the middle of 1944. The Western Allies had landed in Normandy while the greatest Soviet offensive of the war, Operation Bagration, was expected to be launched any day.

The Ryti-Ribbentrop Agreement

Mannerheim was, by now, obviously in a pessimistic mood––understandable as the VT Line had been lost, his troops were retreating, and reinforcements were not in place. He urged that the proposed steps be undertaken quickly since it was not a matter of days but of hours. He soon had a change of heart, probably as a result of promised German assistance and the fact that his troops were fighting successful delaying actions that provided the time needed for reinforcements to arrive.

He concluded that it was risky to burn the bridge to Germany by discussing peace terms with the Soviets until the front had been stabilized. Mannerheim’s changed attitude may also have been influenced by Soviet demands on June 21 that amounted to unconditional surrender.

Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German foreign minister, had arrived in Helsinki on June 22 to enter into negotiations for German assistance. He demanded, in return for aid, that Finland enter into a written agreement with Germany and issue a public statement that it would not seek a separate peace with the Soviet Union. This Ryti-Ribbentrop agreement was reluctantly agreed to by the Finns and resulted in an immediate breach of diplomatic relations with the United States.

Operation Bagration, the massive Soviet offensive against Army Group Center which began on June 22, Allied advances in Normandy, and the British-American offensive in Italy imposed a crushing drain on German resources. Nevertheless, the help provided to Finland by Germany was effective. The shipments of Panzerfausts and Panzerschrecks greatly increased the Finnish Army’s ability to thwart Soviet armor attacks and were instrumental in restoring the fighting morale of the Finnish infantrymen who had previously felt helpless against Soviet tank attacks.

Claims that German aid was only provided as a result of the Ryti-Ribbentrop agreement are not true. The deliveries of infantry light antitank weapons were provided before June 22 without preconditions, as were 150,000 hand grenades. The 303rd Self-Propelled Assault Gun Brigade reached Finland by ship on June 23 and was committed on the front to the east of Viipuri four days later; the 122nd Infantry Division arrived in Finland on June 28. Seven hundred thousand rounds of artillery ammunition, as well as antitank and assault guns, were either sent or ready in German ports for shipment.

Help from the German 20th Mountain Army was out of the question, though. That army was required to guard a long front in northern Finland and the forces were just sufficient for that task. The greatest service it could provide to the Finns was to remain in position and keep the Soviets from penetrating the waistline of Finland and thus threaten the Karelian Isthmus from the north.

The Finns Lose Ground

The Finnish requests for aid kept coming. On June 30, Mannerheim asked for another German division as well as one additional assault gun brigade. This was followed on July 3 with an urgent request for a speedy delivery of rifles and submachine guns.

Mannerheim’s request for another German division came at a time when the central German front in Russia had collapsed. OKW answered on July 5 that it was not possible to accommodate Mannerheim’s request; OKW only agreed to provide heavy weapons and to double the number of assault guns in the 122nd Division.

After Mannerheim protested, Hitler promised two more assault gun brigades, plus tanks and artillery. However, the promise was hollow; the two self-propelled assault-gun brigades ended up being sent to the Eastern Front, one on July 17 and the second on July 18.

In less than two weeks, the Soviets had punched through two of the three Finnish defense lines and were closing in on the third. This represented a serious loss of terrain on the critically important Karelian Isthmus. The Finns now found themselves in the last defensive line before the Soviets reached the open country north of Viipuri––terrain well suited for mechanized forces. The decisive battle for the VKT Line was at hand.

The Finnish troops had fought well against overwhelming odds. Their morale had not completely broken despite heavy losses and continual retreats. Reinforcements had arrived on the Karelian Isthmus from East Karelia and this bolstered their morale.

Finnish historian Matti Koskimaa attributes the loss of ground to lack of operational mobility, inadequate radio communications, and ineffective antitank weapons. He could have added that the failure of the General Staff to recognize the many signs of an imminent Soviet offensive and an unfortunate delay in giving up the forward positions in East Karelia contributed to the loss because reinforcements from there were slow in arriving. However, tough defensive fighting by the Finnish soldiers bought the time required for reinforcements to arrive from East Karelia and for assistance from Germany to help stabilize the situation.

The Largest Battle in Nordic History

The decisive battle between the Finnish Army and the Red Army was about to start in the Tali-Ihantala area on the isthmus between Viipuri and the Vuoksi River. It is often referred to as the largest battle in Nordic history.

The Soviets had suffered significant losses and their troops were beginning to show signs of fatigue. But they had large reserves that allowed them time to rest and reorganize. The elite XXX Guards Corps, for example, had basically rested between June 12 and 24. However, the time was nearing when these Soviet troops would be needed in the great offensive against the Germans. Marshal Govorov received orders on June 21 to be on a line from Lappeenranta to Imatra no later than June 28. He had a short week to accomplish this task.

Govorov’s simple objective was to defeat the Finnish Army in a final battle and then penetrate the defenseless interior of the country. This time he found his task much more difficult. With the arrival of the reinforcements from East Karelia, the Finns had 11 divisions (including the 122nd German Infantry Division) and four brigades on terrain favorable for defensive operations.

When in position, these divisions were deployed as follows: The 10th and 17th Divisions, the Cavalry Brigade, and the Gulf of Finland Coastal Brigade were located in the area north of the Bay of Viipuri under V Corps. The 20th Brigade and the Armored Division were located north of Viipuri. The 18th, 4th, and 3rd Divisions were in line from Tali to Kaupasaari in that order from west to east. The 6th and 11th Divisions were just arriving in the area north of Viipuri. The 2nd and 15th Divisions and the 19th Brigade of III Corps were deployed in that order from north to south along the Vuoksi River.

Having received marching orders from Moscow, Marshal Govorov quickly concentrated his troops in the area to the northeast of Viipuri. The plan was for the Fifty-ninth Army and the Twenty-first Army to drive north; the Fifty-ninth Army was expected to capture Lappeenranta, while the Twenty-first Army turned west north of Viipuri in the direction of Miehikkaela and Hamina. The Twenty-third Army would strike farther to the east with the main force heading for Imatra while part of the army would turn east toward Hiitola.

Four Days of Heavy Fighting

In the initial phase, the Finnish 18th Division, under Maj. Gen. Paalus, along with the 3rd Infantry Brigade and some miscellaneous battalion-size units, faced the 97th and 109th Soviet Corps and the 152nd Tank Brigade. These Finnish units put up a strong defense that gained the time needed for reinforcements to arrive on the scene.

There was heavy fighting at Tali, east of Viipuri, from June 22 onward, in terrain that was well suited for tank operations. A Soviet breakthrough here could bring about the collapse of the Finnish front.

The Soviet attack on the isthmus between Viipuri and Kuparsaari was intensive. For example, on a 15-kilometer-wide sector, the Red Army concentrated 14 divisions, three or four tank brigades, and 70 12-gun artillery batteries. There was an artillery piece every five meters in the areas of the main attacks.

These troops attacked on the morning of June 25 with the main effort along an axis from Tali to Ihantala. The smothering fire from almost 400 tubes of artillery and rocket batteries was directed at the defenders’ front line and as far in the rear as Portinhoikka.

The attack by the 30th Guards Corps tore open the Finnish front between the lakes of Leitimojaervi and Karstilaenjaervi. The Finnish units in the path of this steamroller were the 48th Infantry Regiment and the 3rd Battalion of the 13th Infantry Regiment.

The Soviet infantry, exploiting the intensive artillery preparation, had only to occupy the Finnish lines, as there were no soldiers left alive to offer any resistance. Soviet infantry followed the tanks in a deep penetration that, by the end of the day, had captured Portinhoikka and from there reached halfway to Ihantala.

A Soviet tank spearhead continued in the direction of Juustilankangas but was stopped by a unit of heavy Finnish tanks from the armored division; units from the 18th, 17th, and 4th Divisions joined in the counterattack. The Soviets were thrown back and the Finns reoccupied Portinhoikka in the evening.

In four days of heavy fighting, the Finns––reinforced by fresh units and the 303rd German Assault Gun Brigade––succeeded in sealing the Soviet penetration. However, they were not able to restore the front. The Soviets also reinforced with the 108th Corps.

Battle Groups Puroma and Bjørkman

The Finnish units on the battlefield had become scattered and these were quickly organized into two battle groups, led by Colonels Puroma and Bjørkman. These two battle groups tried to encircle four Soviet divisions and a guards tank brigade that had broken through east of Leitimojaervi. The Soviet divisions established hedgehog positions near Talinmylly and the Finnish attempt at encirclement failed. Throughout the operation, German and Finnish aircraft provided excellent close air support and hammered the Soviet lines of communication.

Although the bold attack by the two battle groups failed, it bought the defenders a sorely needed 72 hours that allowed the 6th and 11th Finnish Divisions to make their appearance on the battlefield. Nevertheless, the Soviets held a dangerous salient near terrain north of Tali that was favorable for tank operations and mobile warfare. Finnish losses were also mounting. By the end of June, Finnish losses had reached 18,000. Only 12,000 of these could be replaced.

The tough defensive fighting of the 18th Finnish Division and the bold actions of Battle Groups Puroma and Bjørkman had stemmed the Soviet offensive long enough for reinforcements to arrive in the form of the 6th and 11th Divisions. The 18th Division was helped immeasurably by counterattacks launched by the Finnish armored division. The arriving 11th Division took over some of the sectors for which the 18th Division had been responsible, and the 4th Division took over defensive positions on the 11th Division’s left flank.

Stabilizing the Frontline

The front line, which had stabilized somewhat over a period of several days of hard fighting, contained several sealed penetrations. For example, a substantial wedge had been driven into the Finnish defensive line north of Repola and the Finns had not been able to eliminate it by counterattacks. Because of the resulting zigzag front, larger forces were needed to man it. General Oesch recommended to Mannerheim that the front be straightened by withdrawals in some sectors and his recommendation was accepted.

Noticing what was happening, the Soviets began a new series of attacks to frustrate the Finnish plan. Consequently, the relief of forces could not be carried out as planned and the straightening of the front was only partially successful. The responsibility for defensive operations on the most northerly front against the center of the main Soviet thrust fell to the 6th Division under Maj. Gen. Einar Vihma.

Despite repeated Soviet tank and aerial assaults, the 6th Division fought a remarkable and tenacious defensive battle, and the Red Army was driven back. German and Finnish aircraft also bombed and strafed bridges and the lines of communication of the forward Soviet troops but Soviet infantry attacks continued with the support of tanks, artillery, and aircraft.

A report by the Finnish General Headquarters on July 1 describes Soviet air formations of up to 200 aircraft and takes note of the destruction of 57 enemy tanks in the Tali area. The Finns were beginning to reap the benefits of their shortened defense line. The Soviet penetration of the Finnish front was limited to a depth of seven kilometers and there was no breakthrough.

A Finnish intercept of Soviet radio traffic on July 3 indicated that several elite Guards and tank units were preparing a decisive attack in the direction of Ihantala. The Finns massed all their artillery fire––from about 250 pieces—and saturated the area where the attack formations were assembling just before the attack was to be launched.

This heavy artillery barrage was followed by attacks by Finnish aircraft and 26 German Stukas from Group Kuhlmey. The heavy defensive curtain of fire completely frustrated the planned Soviet attack, but failed to stop it.

For almost a week, the Soviets continued to carry out combined arms attacks with air support against the 6th Division sector. These attacks were repelled, primarily by excellent use of artillery and mortar fire. The Finnish losses were also great. Among those who were killed was Maj. Gen. Einar Vihma, the division commander. Only minor penetrations of the Finnish line took place and the front was restored through counterattacks.

A Finnish Defensive Victory

The fighting that took place in the Tali-Ihantala area northeast of Viipuri over a three-week period ended in a Finnish defensive victory that impacted later political developments. The fighting was carried out successfully against an enemy superior in both men and matériel but the margin between success and failure was often razor thin. It is ironic that the Soviets were stopped in the same general area as they had been stopped in 1940.

In his book, Bitva zu Leningrad 1941-1944, Lt. Gen. S.P. Platonov does not try to hide the Soviet failure: “The enemy succeeded in significantly tightening is ranks in this area and repulsed all attacks by our troops … the forces of the right flank of the Leningrad front (Marshal Govorov’s) failed to carry out the tasks assigned to them on the orders of the Supreme Command issued on June 21.”

Several elements came together to make Finland’s defensive victory possible. Reinforcements from East Karelia arrived just in the nick of time to prevent a decisive Soviet breakthrough. Finnish defensive operations had become firm and this must, in large measure, be attributed to their new technique in the use of artillery. Like the Soviets, the Finns massed their artillery in the threatened sectors and this had a devastating effect on the attackers.

Also, the new antitank weapons received from the Germans demonstrated their effectiveness even against the heaviest Soviet tanks. The Finnish Air Force, reinforced by Group Kuhlmey, also proved its effectiveness. Finally, the legendary toughness of the individual Finnish soldier had been restored.

Failed Assault on the Bay of Viipuri

On July 13, 1944, Marshal Govorov was ordered to transfer five fully equipped divisions to Leningrad because they were needed in central Russia, and thus he ordered his troops to end their attacks in the Ihantala sector. Finnish intelligence noted that, although Soviet strength on the Karelian Isthmus had grown to 26 infantry divisions and 12 to 14 tank brigades, some of the best Guards units had begun withdrawing and were replaced by less experienced troops.

While the Soviet attacks ended northeast of Viipuri on July 9, the operations on the flanks of the VKT Line continued for a while in the Bay of Viipuri and at Vuosalmi.

A week earlier, on July 2, the commander of the Soviet Fifty-ninth Army, Lt. Gen. Ivan Korovnikov, received orders to cross the Bay of Viipuri with two divisions, one armored brigade, and one naval infantry brigade. The assault troops numbered about 20,000, and were well supported by artillery and close-support aircraft. The initial objective of the amphibious operation, after securing a beachhead, was the town of Tienhaara. The Soviets were obviously trying to develop a threat against the right flank of the IV Corps.

After capturing some islands in the bay, Korovnikov’s Fifty-ninth Army launched the main attack against the northern shore. The Finnish defenders were reinforced by the timely arrival of the 122nd German Infantry Division, and it was in this unit’s sector that the main attack fell along a 10-kilometer-wide front. The 122nd Division had just moved up to relieve the Finnish Cavalry Brigade. The decisive battle in this area was fought from July 8 through July 10.

The Soviet operation was a complete failure as the Germans attacked and drove the landing force into the sea. The defensive operations by the Finns and Germans in the Bay of Viipuri became a victory when Korovnikov received orders to cancel his attacks.

Preventing a Breakthrough Across the Vuoksi River

The III Finnish Corps withdrew to its sector of the VKT Line without serious interference from the enemy. The 2nd Division had been transferred from IV Corps to III Corps and it reached its assigned segment of the VTK Line in the Vuosalmi area. Four battalions of this division––belonging to the 7th Infantry Regiment––were left in a small bridgehead on the western bank of the river while the rest of the division went into positions on the eastern bank.

The commander of the Soviet’s Twenty-third Army, Lt. Gen. Tjerepanov, deployed his forces so that two divisions had the mission of seizing the west bank of the Vuoksi River at Ayrapaa. The fighting for the bridgehead on the west bank of Vuoksi River developed into a fierce battle, Tjerepanov was replaced by Lt. Gen. V. I. Sjvetsov, and the army was reinforced by another corps.

The Soviets launched new attacks on July 3 and 4, but it was not until July 9 that the Finns were forced to give up their positions on the west bank of Vuoksi south of Vuosalmi. The eastern bank of the river also came under attack that day after a heavy artillery bombardment and the employment of several hundred aircraft. Under cover of this strong supporting fire, the Soviets crossed the river in assault boats on a two-kilometer front, seizing a one-kilometer-deep bridgehead on the eastern bank. The Finns lacked the strength to eliminate the bridgehead and could only resort to containment.

Within a short time, however, the Soviets widened the bridgehead to such an extent that they were able to deploy one infantry division supported by tanks. A Jaeger Brigade and assault guns from the Finnish Armored Division were moved from the Tali-Ihantala area to reinforce the III Corps. The Soviets expanded their bridgehead despite these Finnish reinforcements.

Nevertheless, the defenders ultimately limited the dangerous penetration and prevented a breakthrough. The Soviets are reported to have lost 15,000 troops in the Vuosalmi area. Finnish losses were also heavy, primarily in the 7th and 49th Infantry Regiments; these two regiments had 2,296 casualties. The combat activity eventually lessened and the front took on the aspects of trench warfare.

Soviet Withdrawal From the Karelian Isthmus

Serious fighting on the Karelian Isthmus ended by mid-July but went on for some time in East Karelia until the Finns managed to frustrate the Soviet drives in August 1944. The final operation of the campaign took place east of Ilomantsi where Maj. Gen. E. Raappana, with two brigades and two infantry battalions, succeeded in encircling two Soviet divisions––the 176th and 289th––and brought about their virtual destruction. While most of the encircled troops escaped they abandoned their equipment. That operation ended on August 10.

In the period June 18-20, the Finns received information confirming that the Soviets were withdrawing forces from the Karelian Isthmus and transferring them to the area of Army Group North. Some of the forces were replaced with new infantry divisions and fortress units. The Finns estimated that the Soviet forces confronting them now consisted of 29 infantry divisions, two light infantry brigades, 10 armored brigades, and a number of fortress units. These forces were certainly capable of carrying out further offensive operations.

The Germans recalled Air Group Kuhlmey and returned it to the 1st Air Fleet supporting Army Group North on July 21. The Finns had been promised that an additional assault gun battalion would be added to the 122nd Infantry Division, but they were informed on July 22 that this battalion would not be coming.

Negotiating an Armistice

Finnish alarm increased on July 29 when Hitler ordered the 122nd Division back to Army Group North. The OKW explained that the quiet situation in Finland was the deciding factor in the division’s withdrawal and that the Germans would come to Finland’s aid in the future if they were needed. The sector held by the 122nd Division was taken over by the Finnish 10th Division.

Aside from dwindling German assistance, the gravest problem facing the Finnish Army in the middle of July 1944 was lack of manpower. Their losses had continued to rise at an alarming rate, reaching 32,000 by July 11 and 44,000 by July 18. Older members of the reserve were redrafted and year groups 1902-1908 were called to the colors. However, these measures produced only 31,700 troops as replacements for the 44,000 who were lost.

Soviet losses were considerably larger than those for the Finns, but an accurate number is difficult to establish since casualty figures for the Leningrad Front do not distinguish between the Karelian Isthmus and other sectors of the front. It is estimated, however, that Soviet losses in the first four days of the offensive against Tali-Ihantala came to about 22,000 killed, wounded, and missing. They are also reported to have lost 300 tanks in the Tali-Ihantala area.

The stabilization of the front provided the prerequisite that Mannerheim had laid down for an approach to the Soviets for an armistice. The Soviets continued to withdraw forces from the Finnish fronts and on the Karelian Isthmus they were reduced to 10 infantry divisions and five tank brigades by the middle of August. Mannerheim also accepted the position of president.

The reversal of Finnish policy started with a repudiation of the agreement it had made with Germany six weeks earlier, followed by a petition to the Soviet Union for peace. The Germans had no power to influence events.

On August 29, the Soviet Union sent its conditions for accepting an armistice delegation. First, Finland had to make an immediate public declaration that it was breaking diplomatic relations with Germany. Second, Finland had to publicly demand that Germany withdraw its troops from Finland by September 15. Any German troops remaining in the country after that date should be disarmed and handed over as prisoners to the Soviet Union. Finland accepted these armistice terms and the guns fell silent on September 5, 1944.

The VKT Line Saved the Finland

The tenacious Finnish defense of the VKT Line secured that country’s continued existence as an independent nation, much as their defense in this area had done in 1940. There is little doubt that Finland would have shared the fate of the Baltic States, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia if the VKT Line had not held. However, there were other factors at play.

Aid from Germany was instrumental in successful Finnish delaying actions and the stabilization of the front along the VKT Line. The outcome would have been different if it were not for German matériel and manpower assistance at a time when Germany needed all available resources for its own fronts.

Stalin had undertaken the offensive against Finland as a means of filling the time before the scheduled massive offensive against Army Group Center in western Russia. He wanted to see how the Allied landings in France developed before launching this offensive. When the Normandy landings were successful and the Allies began their breakout from the beachheads, the most important Soviet objective was to meet the Americans and British as far west as possible. The offensive in Finland took a distant second place to this objective. Having driven the Finns back to the VKT Line afforded the Soviets an opportunity to offer the Finns acceptable armistice terms, but terms that still left the country within the Soviet sphere of influence.

This does not distract from the splendid achievement of the Finnish soldiers who sacrificed so much for their country against overwhelming odds in June-July 1944. The loss of almost 50,000 soldiers in a nation with a population of only four million speaks for itself. And as they had so often in the first half of the 20th century, the Finnish soldiers had demonstrated their mettle. n

One lesson in this operation that is useful today is that a determined country, though lacking some of the resources of a larger attacker, can make that attack so prospectively costly that it may never take place. This is useful in considering the possible actions by Xi and Putin. Putin was able to take Crimea and parts of Eastern Ukraine because he met no opposition. Mao took Hainan Island, but not Taiwan for the same reason. A well armed small country can be quite a discouragement to outside aggression by applying the porcupine principle of threatening a possible attacker with a pyric victory.

Donald Link, I would agree that that is the only reason why China hasn’t invaded Taiwan and Russia hasn’t invaded Ukraine, in force. The thought that the Western powers, or even the US alone, would stand up to them, is tempering their behavior, for the moment. Those 2 countries want that territory badly (ex-KGBer Putin longs for the good old days of Soviet domination, and the Chinese Communists would see conquering Taiwan as a feather in their cap of finally having all traditional Chinese territory). They know how to use force, whether against their own people or as conquerers of others. Time will tell whether we’ll continue to be willing to defend Ukraine and China, either as a allied coalition or by our ourselves. Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1787 that “the tree of liberty must, from time to time, be refreshed with the blood of patriots and tyrants”. As long as the West will stand by those threatened people, the East will have to calculate how much it’s really going to cost them to get the territory, and the people, that they want.

RIP MIA Matti Kaario (my second cousin), Finnish army, Valkeasaari, 10 June 1944.

Great story. I always wondered about Finland in WWII. Well done! Great people.