By David A. Norris

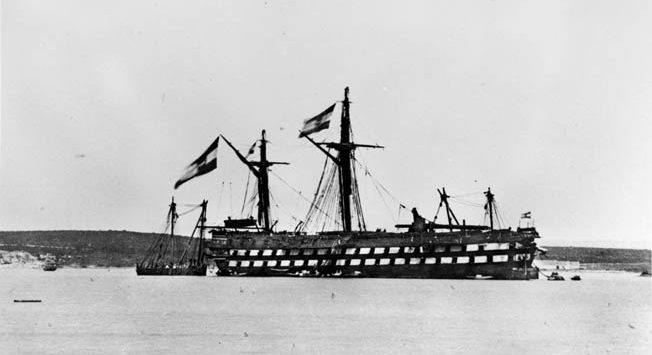

Narrrowly avoiding a fatal blow from the Italian ironclad ram Affondatore, Commodore Anton von Petz, commander of Austrian wooden-hulled ship of the line Kaiser, came under fire from the heavy rifled guns of another enemy ironclad, the Re di Portogallo, on July 20, 1866, near the Dalmatian island of Lissa in the Adriatic Sea. This time, instead of evading the other vessel, Petz brought his ship on a collision course with the enemy’s armored hull. The 92-gun Kaiser supplemented a full set of sails with a two-cylinder steam engine. Gathering speed and momentum from her boilers, one of Europe’s last wooden ships of the line was seconds away from ramming one of Europe’s first ironclad warships in a history-making naval encounter of the Third Italian War of Independence.

For centuries Italy had been a collection of divided and rival monarchies, some of them under foreign control. The post-Napoleonic political order left much of Italy under the rule of Austria’s Hapsburg dynasty. Three wars were fought to unite Italy and win its independence. Each of these wars placed the Austrians against the Italian forces and their allies. Dominant among the Italian states, the Kingdom of Sardinia grew as it annexed the Austrian territory of Lombardy, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Tuscany, and several smaller principalities after the second war in 1859. In 1861, the combined nation was proclaimed the Kingdom of Italy. King Victor Emanuelle of the Sardinia-Piedmont became the new country’s first king. Unification was not yet complete. French troops still garrisoned the remnants of the Papal States around Rome, and Austria still controlled Venice.

Ironclad warships like those participating in the Battle of Lissa had three primary characteristics: an armored hull, steam propulsion, and guns capable of firing exploding shells. An early version of the ironclad was first used during the Crimean War when the French employed floating ironclad batteries against Russian coastal fortifications on the Kinburn Peninsula in October 1855. It was an impressive debut. Despite receiving fire from Russian batteries, the ironclad batteries in concert with wooden warships destroyed the Russian forts in just three hours.

Seven years later, Union and Confederate ironclads clashed at Hampton Roads during the American Civil War on March 8-9, 1862. The battle on the Eastern Seaboard of the United States marked the first true naval combat between vessels built of iron rather than wood. Union and Confederate ironclads saw more action during the conflict, and European naval officers and ship designers eagerly studied accounts of these encounters. However, no bat- tle between fleets of ironclads occurred during the four-year conflict. That landmark event occurred about a year after the end of the war when approximately 20 ironclad ships of the Austrian and Italian navies fought at Lissa.

By European standards, the navies that clashed off Lissa were both new. Italy’s navy, the

Regia Marina, was formed in 1861. It was predominantly a combination of the navies of Sardinia-Piedmont and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies with contributions from smaller states. Count Carlo Pellion di Persano, a veteran officer of the old Sardinian navy, commanded the united maritime force of the new kingdom. Persano had joined the

Sardinian navy in 1824 and advanced rapidly through the ranks. He commanded the Daino during the First Italian War of Independence in 1848-1849 and a decade later participated in naval actions as a rear admiral during the Second War of Italian Independence for which he was promoted to vice admiral. In 1862 he became Italy’s Minister of Marine and afterward rose to full admiral.

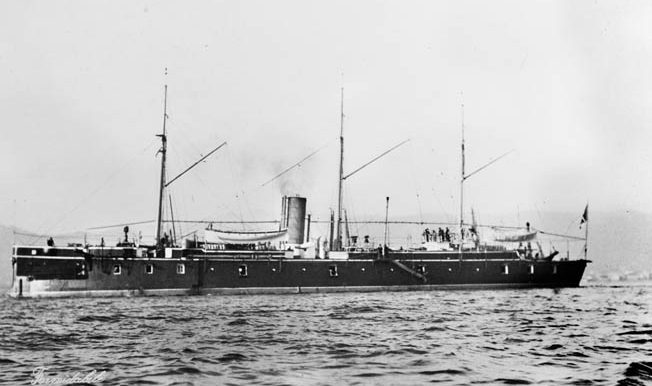

With part of their country still under Hapsburg rule, the Italians saw Austria as their most likely adversary in a new war. In a major expansion and modernization program, two oceangoing ironclads were ordered from New York shipbuilder William H. Webb. The Webb vessels were the armored frigates Re d’Italia and the Re di Portogallo. At 5,700 tons each and plated with 4.5- inch armor, both ships carried impressive batteries of heavy rifled and smoothbore guns.

The New York Times reported that the engines of the Re d’Italia were built at the Novelty Iron Works, the same firm that built the distinctive turret of the USS Monitor. When first contracted by the Italian government in 1861, the Re d’Italia was begun as a wooden steam frigate. After the ironclads Monitor and CSS Virginia fought at Hampton Roads, plans were changed to include armor plating for the Re d’Italia. The design left the propellers and rudder unprotected by armor. Two smaller ironclads, the 2,700-ton iron corvettes Formidabile and Terribile, were purchased from France. An armored turret ship, Affondatore, was built in England. Essentially a double-turret monitor, the Affondatore carried only two pieces of artillery, both 10-inch Armstrong guns. The Austrian Empire arose from the land- locked interior realms of the Continent, and for centuries its Hapsburg rulers paid little attention to naval affairs. In the 1797 Treaty of Campo Formio, the Hapsburgs swapped the Austrian Netherlands with Revolutionary France in exchange for Venice and the Adriatic coastal regions of Istria and Dalmatia. With Venice came a ready-made navy for the Hapsburgs.

Twenty-two-year-old Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian was placed in charge of the Imperial and Royal War Navy in 1852. Despite his youth, the archduke was an excellent choice as commander-in-chief. He had spent a few years at sea in the navy. His royal status gave the imperial sea service a much-needed advocate. A forward-looking reformer, Maximilian modernized the Austrian navy. When the archduke left his post in 1861, his navy was well on its way to world-class status. In the early 1860s, the Austrians began acquiring up-to-date ironclad steam warships, all of which were built in their own Adriatic shipyards.

Beside a trend toward ironclad war vessels, the navies of Austria and Italy had another factor in common: their crews spoke several different languages. Austrian officers gave their commands in German, the official language of the navy. However, many of the crewmen spoke Croatian, and many others spoke Italian dialects. When Austrian officers gave orders in German, petty officers had to translate for most of the crew.

At the time of unification in 1861, the great majority of Italians spoke regional dialects rather than standard Italian. Adding to the language differences were rivalries between the former officers of the old navies of the Italian states.

War broke out between Austria and Prussia on June 14, 1866. This conflict, the Seven Weeks’ War, would determine whether the German states united under the wishes of Prussia or the Hapsburgs. Prussia’s ally Italy declared war on Austria on June 19. The Prussians wanted the Italian army and navy to distract the Austrians as much as possible.

Before the outbreak of the war, Admiral Persano took stock of the state of the navy. He had well-armed modern ships but was short of trained gunners, engineers, and warrant officers. He warned the naval ministry on May 21 that the fleet was unprepared for war. “It would take three months to make it tolerably ready,” he told the ministry.

Rear Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff to command of the Austrian battle fleet. He had a proven track record having led the North Sea fleet both in the Second Schleswig War of 1864 and the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. His performance in the former won him promotion to the rank of admiral. Stubborn and tending to offend superiors with his blunt opinions, Tegetthoff’s courage, efficiency, and ability to command more than compensated for his troublesome temperament. Although strict, he was fair and considerate to his subordinates, gaining their trust and admiration. He led with a steady hand in a time of technical transformation for European navies and exhibited superb command skills and impressive tactical ingenuity.

Tegetthoff pushed to complete the unfinished ironclads Erzherzog Ferdinand Maximilian (known as the Ferdinand Max) and Habsburg. Their new Krupp guns had not arrived, so he armed the ships with old-fashioned 48-pounder smoothbores. He was soon ready to take the fleet to sea.

On June 27, Tegetthoff’s fleet appeared off the Italian naval base at Ancona, roughly 125 sea miles southeast of Venice. The ships at Ancona were coaling, and two of them were still bringing guns on board. On the Re d’Italia, the crew was fighting a coal fire. The Re di Portogallo was unserviceable because she had water in her cylinders. None of the ships was ready for battle. Tegetthoff lingered off the coast for a few hours and then steamed away.

Spurred by demands from Prussia for action, the government ordered Persano out to sea. He left Ancona on July 8, spent five days steaming through empty waters, and returned to port.

Still under pressure from the government, Persano decided to capture Lissa. Held by an Austrian garrison, Lissa was 10 miles long and five miles wide. The island’s sea-going inhabitants worked the sardine fisheries in the offshore waters, and farmers produced wine, almonds, and figs. The British had occupied Lissa during the Napoleonic War, and the Royal Navy had achieved a minor naval victory near the island in 1811. After the final downfall of Bonaparte, the British returned Lissa to the Austrians.

The British left three Martello towers on the island, as well as British-built fortifications. Martello towers were small, round coastal forts that the British erected throughout their far-flung empire. In the intervening years, the Austrians augmented Lissa’s defenses.

By mid-July, rumors reached Tegetthoff that negotiations were underway to transfer Venice to Italian control. He had 800 Venetians with his fleet. Concerned about the reaction of the 800 Venetians with his fleet, the admiral requested permission to put them ashore if the city was given up. “Venice not yet given up; task of the squadron unchanged,” was the reply he received. This helped restore morale when Tegetthoff revealed it to his crews.

On July 16, Persano left Ancona with a fleet of 34 ships, including 12 ironclads, 14 wooden warships, five small dispatch vessels, and three troop transports. For amphibious assaults on Lissa, he could spare only 500 marines and 1,500 sailors.

On the night of July 17, the Italian fleet neared Lissa. The mountainous island had three harbors. San Giorgio, the well-fortified main harbor, was on the northeast of the island. Two smaller harbors, Comisa and Manego, were defended by forts and guns on high ground, and their garrisons were prepared to fend off naval attacks. Comisa was on the western side of the island, and Manego on the southeastern side.

Two days of bombardment damaged the Austrian forts, but the garrisons held off the ships. Persano’s fleet suffered 16 men killed and 114 wounded, and several of the ships were damaged. On the night of July 19, Tegetthoff was steaming toward Lissa. After considering how a battle might unfold the next day, he gave detailed action plans to all of his captains. If signals were unreadable or the admiral fell in the action, his officers would know what to do.

The Austrians were outnumbered with only seven ironclads with 88 guns against a potential 13 armored Italian ships carrying 103 guns. Overall, the Italian ships were more modern, better armored, and possessed greater tonnage and horsepower. Two Italian ships boasted a pair of men- acing 10-inch, 300-pounder Armstrong guns. The ships of the fleet also had among them six 8- inch Armstrong guns and a variety of 7-inch and 8-inch guns, the majority of which were long- range rifled pieces.

The Austrian wooden warships carried a few rifled guns, but most of their armament consisted of 30-pounder smoothbores. None of their guns was larger than 48 pounds, and all were smaller than any of the guns on the enemy’s main vessels. Well aware that the enemy fleet outgunned him, Tegetthoff instructed his captains to rely on ramming and gunnery against the Italian vessels.

On the morning of July 20, the garrison of Lissa saw little through the rain and mist that cov- ered the island and the surrounding waters. They expected the landing of the enemy marines and naval infantry.

The little Italian dispatch vessel Esploratore appeared at 8 AM after leaving her station, signaling that the enemy was in sight. News of the approach of the Austrian fleet was a shock to the Italian officers. The fleet was scattered around the island preparing for bombardments and troop landings. Two ironclads had broken engines and another, the Formidabile, was engaged in transferring 50 wounded men to a hospital ship.

In the preceding weeks, Tegetthoff had emphasized gun drill with his crews, while the Italian sailors were given little training with their new rifled guns. Persano had not prepared a battle plan, and he had held no discussions about tactics with his captains. Indeed, Persano scoffed at the enemy’s arrival. “Behold the fishermen!” he said.

For Tegetthoff and the Austrian fleet, it had been a rough morning. Squalls stirred up rough seas, and heavy rain lashed the ships. So violent were the waves that the smaller ironclads were compelled to shut their gun ports. For a time, it looked as if the weather might prevent the impending battle. At 10 AM, the sun burned away the mist. The Austrian soldiers in their battered fortifications cheered as they saw their fleet in the distance, steaming toward them from the northwest.

Tegetthoff arranged his fleet in three arrow-shaped divisions that bore down rapidly on the enemy. His lead division of seven ironclads was followed by the steam-powered ship of the line Kaiser and five wooden steam frigates, and a last division combining the smaller wooden vessels. The latter division included the Greif, the emperor’s paddle-wheel steam yacht, which was pressed into service as a dispatch boat.

As the enemy neared, Persano had 10 ironclads present and ready for action. One ironclad, the Terribile, was en route from Comisa. Another ironclad, the Formidabile, was incapable of battle because of damage from the Austrian shore batteries on Lissa. Under Vice Admiral Giovanni Battista Albini, the wooden vessels clustered off the north coast of Lissa and took little part in the battle. Following a practice used during the American Civil War, some of the wooden ships hung heavy iron chains over their sides to give some protection to their engines and hulls.

Persano’s ironclads formed a line, steaming north of Lissa in a northeasterly direction. While the enemy approached, the Italian commander made the disastrous decision to shift his flag from the Re d’Italia to the tenth available ironclad, the Affondatore. The remainder of his armored ships ended up in three divisions of three ships commanded by Rear Admiral Giuseppe Vacca, Captain Emilio Faa di Bruno, and Captain Augusto Riboty.

Halting to change flagships opened a large gap in the line of battle because the three vessels in the lead kept steaming ahead. Persano later explained that he wanted to direct the battle “outside the line in an ironclad of great speed, to be able to dash into the heat of bat- tle, or carefully to convey the necessary orders to the different parts of the squadron.” Unfortunately, the admiral had not mentioned this move to his captains beforehand, and most of them were too far away to see that the Affondatore was now their flagship. During the battle, most of the fleet watched in vain for signals from the Re d’Italia. At any rate, the Affondatore’s low freeboard and minimal array of two bare pole masts made her poorly suited for displaying signal flags.

Tegetthoff’s course took his fleet nearly at a right angle toward the Italian line. Rear Admiral Vacca’s flagship Principe di Carignano, which was first in line, opened fire at 10:43 AM. One of the first shots struck the Austrian ironclad Drache, killing her commander, Captain Heinrich Freiherr von Moll.

Gunfire flashed from one ship after another. Tegetthoff was in the lead aboard the Ferdinand Max. He steamed into battle smoke that was so thick that he initially was unaware that he was leading his division through a gap in Persano’s battle line. Vacca’s three ships turned to port to flank the first division of enemy vessels and to get closer to the vulnerable unarmored ships in the rear divisions. Three Austrian ironclads to port of Tegetthoff steered to block Vacca, while the three to starboard veered to confront the remaining enemy ironclads.

The Ferdinand Max passed completely through the enemy line then turned back to confront the enemy center. Captain Maximilian Daublebsky von Sterneck climbed halfway up the shrouds to get a better vantage point.

Battle formations dissolved into a melee as ships maneuvered on their own, seeking to ram opponents or avoid collisions. With the poor visibility, it was difficult to distinguish national ensigns. All the Italian ships were painted gray, and the Austrians were painted black, although each funnel was painted with individualized color trim. Tegetthoff sent no signals after the firing began, but his captains had their instructions, which told them to ram everything gray.

On the Affondatore, Persano tried to ram the Kaiser. With its 10-inch Armstrong rifles blazing from both turrets, the Affondatore hit the Kaiser several times with 300-pound shells. One of these huge shells dismounted a gun on the Austrian deck, and mowed down six men at the helm. But the ship of the line evaded the Italian ram and delivered two damaging broadsides.

The Affondatore drew off and then sped toward the Kaiser for another attempt at ramming but once again missed. Both vessels scraped close together. Small arms fire mortally wounded an Austrian officer, an ensign who was posted in the mizzen top. It was becoming clear that ramming an enemy vessel that was underway was not as easy as it seemed. For the ironclads, a full turn took several minutes, while most of the time a quick adjustment of the helm was enough for a potential target to change course and avoid being hit.

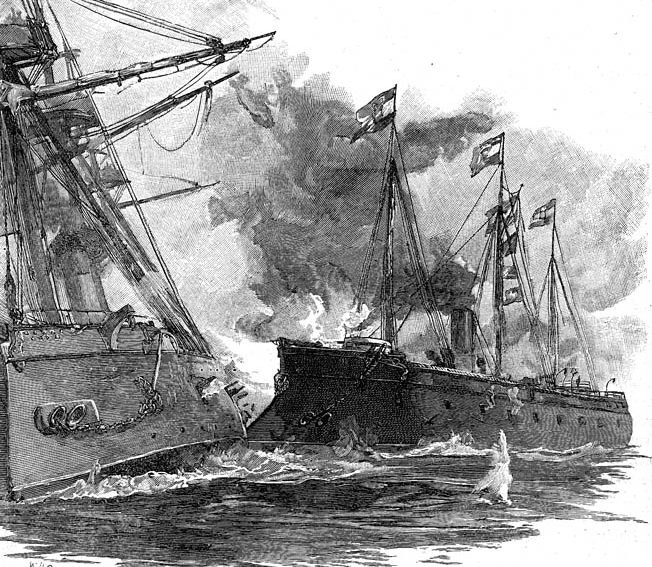

Eluding the Affondatore, the Kaiser was confronted by another ironclad, the Re di Portogallo. The latter, with the armored ships Maria Pia and Varese, attacked the wooden ships of Tegetthoff’s second division. Some of the shells soared over the Kaiser and hit other vessels, and one shot killed the captain of the screw frigate Novara. The wooden-screw corvette Erzherzog Friedrich and the paddle-wheel dispatch boat Kaiserin Elisabeth were in danger of destruction by the Re di Portogallo.

No Austrian ironclads were at hand, so Commodore Petz brought the Kaiser’s prow on a course to ram the Re di Portogallo amidships. The Re di Portogallo altered course just in time to soften the blow inflicted by the Kaiser. As the ships crashed at 11 AM, the oak prow of the Kaiser dented the ironclad’s armor. Between the sharp impact and a broadside from the Italian ship, the Kaiser lost her bowsprit and part of the stem. The foremast collapsed and, falling backward onto the deck, crushed the funnel. The Austrian crew hacked at the wreckage but could not prevent the tangle of wood, canvas, and rigging from catching fire. Broken off in the collision and left on the deck of the Italian ironclad was the Kaiser’s figurehead, a statue of Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph.

Petz inflicted some damage on the ironclad. Eleven port lids were smashed and two anchors and a field gun on the deck of the Re di Portogallo were knocked overboard. As the ships exchanged broadsides, several Austrian shots struck the Italian ship’s hull below the armor plating.

While the wreckage of the Kaiser’s foremast continued to burn, more shells plowed into the ship of the line and knocked out some of the forward guns. The steering gear was damaged, and with- out the funnel the engineer could raise but little steam. Petz headed for safety at San Giorgio, and several of the wooden vessels clustered around to protect the Kaiser.

Persano on the Affondatore steamed forward to ram the Kaiser. A square hit amidships would have sunk the ship of the line. At the last moment, Persano ordered the helm turned to miss the Kaiser. The admiral later stated he gave the order because the enemy ship was already helpless. Just the same, the Italian vessels pounded the crippled ship with their guns until the Kaiser was able to draw out of range. A single shell from the Affondatore killed or wounded 20 men.

The Ferdinand Max twice tried to ram enemy iron- clads. The second try yielded a trophy when the enemy’s mizzen topmast and gaff snapped and fell onto the forecastle of the Austrian ship. Quartermaster Nicolo Car- covich ran forward. Under heavy small arms fire, Carcovich tugged at the Italian ensign. Finally pulling the flag free, he fastened it to a stanchion. It is believed the captured flag came from the Palestra. In the apparent mistaken belief that the Re d’Italia was still the enemy’s flagship, the Austrians targeted that vessel. Four ironclads including the Ferdinand Max beset the Re d’Italia, which in turn was assisted by the Palestro.

Austrian shot bounced off the plating of the Palestro, but only one-fourth of the vessel was armored, protecting the engine room but little else. A shell smashed through the unprotected wooden stern and set the wardroom on fire. With flames spreading close to the magazine, the Palestro dropped out of action to deal with the fire. Meanwhile, the steering gear of the Re d’Italia was hit and the ship steamed slowly amid the Austrian vessels. Captain Sterneck, still watching from high up in the shrouds, ordered the Ferdinand Max to ram the enemy vessel. When it was just a few hundred feet from the Re d’Italia, Sterneck ordered the engines to stop. That way the ship would be ready to reverse engines and back away from the enemy’s crushed hull before the two vessels locked together. As the engineers awaited their order, momentum carried the ship ahead at 111/2 knots.

Aboard the Re d’Italia, Captain Faa di Bruno made a fatal error as the Austrian armored frigate loomed off his port side. He was running ahead at full speed, but another Austrian ship blocked his path. Rather than push ahead and ram the ship off his bow, Faa di Bruno decided to reverse engines to elude the Ferdinand Max.

But there was no time to finish the maneuver. The Re d’Italia ceased forward motion and stopped dead in the water. Before the ship could begin backing out of harm’s way, the Ferdinand Max struck the Re d’Italia amidships on her port side. The iron ram punched through the armor and heavy timbers into the engine room. An 18-foot-wide hole, half of it below the waterline, let in a flood of seawater. For a few moments, the stricken ship lurched 25 degrees to starboard, exposing to view the fatal wound in her hull. The starboard tilt stopped, and then the ship tipped back to port. Righted for only an instant, the roll to port accelerated and water rushed in through the hole.

Aboard the Ferdinand Max, the chief engineer reversed the engine when he felt the impact, and the vessel steamed backward clear of the enemy hull. Aboard the doomed ship, the chief gunner saw one of the cannons on deck had been loaded but not fired. “Just this one more,” he cried and fired the last cannon shot from the sinking ship. Some accounts stated that Captain Faa di Bruno then shot himself with his revolver. Conflicting accounts say he jumped overboard and was pulled down by the sinking ship.

With the deck awash, Italian marines climbed aloft into the rigging. They fired at the Austrians, hitting numerous sailors before the masts disappeared as the ship slipped downward into 200 fathoms of water. An Austrian officer who glanced at his watch was astonished that scarcely 11/2 minutes elapsed between the moment of collision and the sinking of the enemy ship. By 11:20 AM nothing was left but scattered survivors swimming in the sea or clinging to bits of floating wreckage. The firing had begun only 40 minutes earlier.

Before Sterneck’s crew could lower their one remaining undamaged boat to start picking up survivors, another Italian ironclad (believed to be the Ancona) loomed out of the smoke. Apparently unaware that scores of the crewmen of the Re d’Italia were still in the water, the ironclad aimed to ram the Ferdinand Max. The Austrians averted a collision, but the ships passed so closely together that their forward gunners could not maneuver their rammers to reload.

The Italian vessel fired several rounds at point-blank range. Although the guns flashed fire and bellowed smoke, there were no signs of any projectiles. With great relief, sailors aboard the Ferdinand Max wondered if the enemy had fired at them with unshotted guns. Indeed, this may have been what happened. The Ancona’s captain later reported that his muzzle loaders were packed with their powder charges before the gunners were told whether to load iron or steel shot. In the chaos of battle, his gunners sometimes fired without ever adding projectiles.

To avoid meeting the same fate as the Re d’Italia, the Ferdinand Max steamed away. Of the crew of 600 aboard the sunken ship, only nine officers and 159 men were saved. Most of them were picked up by Italian vessels, although 18 men survived by swimming to the shores of Lissa.

Firing and maneuvering continued, but the battle wound down as the fleets drew apart. Before the smoke cleared two of Persano’s ships, the Ancona and the Varnese, collided. Damage was slight, but their rigging was entangled, and it took some time to separate themselves. Another collision between the ironclads Maria Pia and San Marino injured the latter ship so severely that it was unfit for continued fighting.

At 12:10 PM, Tegetthoff signaled his vessels to close in on his flagship. One and a half hours after the first shot, the main action of the Battle of Lissa was over.

The Kaiser headed for San Giorgio with her wooden escorts. Fire still raged aboard the ship of the line, and she was menaced by the Affondatore, which made several attempts to ram. Enemy vessels fired from long range, but two Austrian ironclads arrived to guard the Kaiser. At 1:15 PM, the ship of the line was off San Giorgio and the crew redoubled their efforts to douse the fire on board.

Smoke gradually drifted away from the now silent guns of Persano’s fleet. The admiral, unable to spot his old ship, signaled, “Where is the Re d’Italia?” Several vessels responded that it had been sunk.

Persano intended to continue the battle, and with the Affondatore steamed toward the division of wooden vessels off Lissa. With them was the ironclad Terribile, which had arrived from Comisa but lingered with the wooden ships while taking little part in the battle. In contrast with the assertive and risky roles played by some of the Austrians’ wooden ships, Albini seems to have felt that his unarmored vessels had no place in such a battle. Persano sent several signals to rally his ships in pursuit of the Austrians, but few answered his call as the enemy fleet steamed away toward San Giorgio.

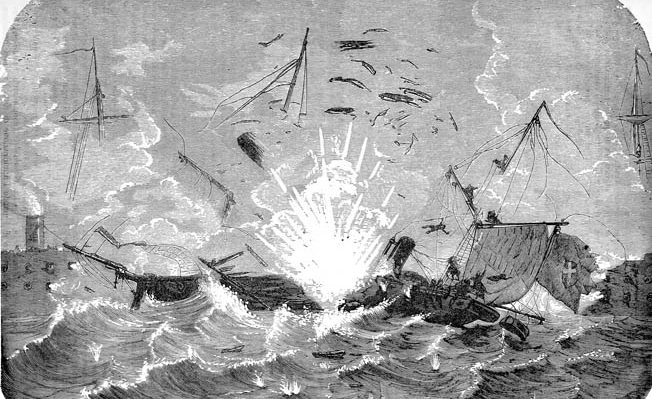

One more disaster was yet to befall the Italian fleet. Commander Alfredo Capellini’s crew still fought the fire that broke out in the wardroom of the Palestro. Flames spread to some extra stocks of coal that were piled on the deck to increase the ship’s cruising range. Several boats were offered to take his crew to safety. “Those who wish to go, may go; for my part, I remain,” said Capellini, who refused to abandon ship. His crew followed their captain’s lead, and only the wounded consented to being put aboard the boats.

In desperation, Capellini flooded the Palestro’s powder magazines, and it seemed that the ship was then saved. But a supply of shells had been stored outside the magazine for easier access during the battle. At 2:30 PM, the flames reached these shells, and the Palestro exploded. Witnesses in both navies saw fire flash out of the gun ports. Sailors and wreckage soared high into the air. A few minutes later the wreck disappeared beneath the surface. Only one officer and 19 sailors of the 250-man crew survived.

Tegetthoff’s ships were in San Giorgio by sunset. Their dead and wounded were taken ashore. Four vessels patrolled outside the harbor during the night while repair work went on aboard the damaged vessels. Early on the morn- ing of July 21, every ship other than the Kaiser was ready to renew the battle. But a signal sta- tion reported that the only sight of the enemy, a distant smudge of smoke to the north-northeast, had disappeared. Persano’s ships, already far from the scene, anchored at Ancona later that morning.

Austrian losses came to three officers and 35 men dead and 15 officers and 123 men wounded. Two-thirds of the dead and wounded were aboard the Kaiser, which was the hardest hit of Tegetthoff’s ships.

Directly from enemy fire, the Italian ships lost only five men killed and 39 wounded. It was a total far less than the cost of the bombardment of Lissa. The death toll, though, rose as high as 667 because of the sinking of the Re d’Italia and the explosion of the Palestro.

Tegetthoff was promoted to vice-admiral hours after news of the battle reached Vienna. Back in Italy, Persano tried to pass off the action as a victory. Public opinion turned against the admiral as details of the battle and the loss of two of the navy’s finest ships became known. Tried by the Italian senate, Persano was found guilty of negligence and incapacity and dismissed from the service. Although he had reported Albini and Vacca for disobedience of orders for their failure to follow him to renew the battle, they were allowed to testify against him during the proceedings.

Austrian success at Lissa ultimately meant little. Prussia defeated Austria in the Seven Weeks’ War, which ended in August 1866. Under pressure from the Prussians, and with French mediation, Austria was compelled to give up Venice. Rather than transfer the venerable city-state directly to Italian control, Austria transferred the territory to France, which ceded Venice to Italy. Possibly, Tegetthoff’s victory at Lissa contributed to Austria’s retaining control of its other Adriatic coastal possessions.

Lissa was the largest battle involving a European navy between Navarino in 1829 and the Battle of Tsushima Straits in 1905. The 1866 clash involved more ships that did the Spanish- American War actions at Manila Bay or Santiago de Cuba in 1898. Thus, in an age when naval strategists were evaluating the ironclad warship, the battle attracted considerable attention. Unlike the age of wooden warships, the heyday of the ironclads, which lasted from 1805 to 1905, passed quickly.

Had a veteran of British Admiral Horatio Nelson’s fleet seen the Battle of Lissa, he would certainly have recognized the familiar sights of a forest of masts and spars rising from a thick haze of powder smoke. Yet the future of naval warfare was plainly evident with steam-powered armored vessels, large modern rifled guns, and steel projectiles. There were no boarding parties, and no prizes were taken. Symbolic of the passing of the old navies, the stalwart wooden ship of the line Kaiser was converted into an ironclad in 1871. For more than three decades after the Battle of Lissa, though, the fate of the Re d’Italia meant that warships of the world’s large navies were still designed as rams and gun platforms.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments