By Richard Higgins

“We were stunned when we entered the camp,” Yoshio “Yosh” Nakamura said, remembering the day when he and his family, from El Monte, California, were herded through the main gate at the Gila River Relocation Center—a Japanese American internment camp 30 miles southeast of Phoenix, Arizona—carrying only suitcases into which their worldly possessions had been crammed.

“There was a wire perimeter, searchlights, armed sentries,” he recalled. “It was demoralizing—traumatic, even.”

Rose Tanaka, who, at age 15, was sent to California’s Manzanar War Relocation Center, reflected, “They looked at us as if we had no allegiance to real Americans—it was in our blood; never mind if we were American citizens by birth. All of a sudden, I felt the hatred from other Americans against us.”

Like tens of thousands of other Americans of Japanese heritage after December 7, 1941, the Nakamuras and Tanakas suddenly found themselves treated as enemy aliens, spies, potential saboteurs. Worse, they found themselves uprooted from their homes and placed in internment camps far inland.

During the war, 10 major internment camps—officially called “relocation centers”—were established by the U.S. government in Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming for the purpose of segregating those who were deemed possible threats to the American homeland.

The forced relocation and internment of Japanese Americans during World War II remains a stain on this nation’s deeply held belief in personal rights and the due process of law. The rounding up of over 120,000 American citizens and noncitizens of Japanese descent in the wake of Pearl Harbor and their three-year journey through a process of legal persecution and forced removal to spartan camps in hostile environments left damaged lives and trampled liberties in its wake.

Of course, the fear and anger aroused in America by Japan’s attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet and military installations is not hard to understand. America wanted someone to blame and to punish, and anyone who “looked Japanese” was considered by many to be fair game; internment camps seemed to be the quick and easy solution. But America’s war against fascism lost some of its moral purity due to this event.

“Ill-Advised, Unnecessary and Unnecessarily Cruel”

How did some of the major government participants in the relocation effort later reflect on their actions? While believing in the context of the time that evacuation and internment were a legitimate exercise of the War Powers Act of 1941, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson recognized that, “to loyal citizens this forced evacuation was a personal injustice.” In his autobiography, Francis Biddle, U.S. Attorney General in 1941, reiterated his beliefs at the time: “The program was ill-advised, unnecessary and unnecessarily cruel.”

Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, who joined the majority opinion in Korematsu v. United States, which held the evacuation constitutionally permissible, found that the evacuation case “was ever on my conscience.” Milton Eisenhower, brother of Dwight D. Eisenhower and the official in charge of the relocation program, later described the evacuation to the relocation camps as “an inhuman mistake.” Chief Justice Earl Warren, who, as Attorney General of California had earlier urged evacuation, stated, “I have since deeply regretted the removal order and my own testimony advocating it, because it was not in keeping with our American concept of freedom and the rights of citizens.”

A commission established by President Jimmy Carter in 1980 and issuing its report in 1982, Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, which formed the basis for Ronald Reagan’s official apology in 1988 and offer of restitution, observed, “The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership. Widespread ignorance of Japanese Americans contributed to a policy conceived in haste and executed in an atmosphere of fear and anger at Japan.

“A grave injustice was done to American citizens and resident aliens of Japanese ancestry who, without individual review or any probative evidence against them, were excluded, removed and detained by the United States during World War II.”

How did this happen? Was there any resistance to the decision? Why was there an absence of “political leadership” in what looks like a gross injustice today? Finally, how did the heroic performance of the fighting Nisei contribute not only to the war effort but the future of civil rights in America?

To answer these questions and understand the legacy of race prejudice and jealousy that led to the promulgation of “a grave injustice,” we must start at the beginning of the relationship between various Asian ethnicities and the population of the United States in the 19th century.

Mass Migration From Asia

The issue began with the original United States Immigration and Naturalization policy, which granted citizenship only to free “white” male immigrants. This was later extended by the 14th Amendment to any child regardless of their parents’ race, citizenship, or place of origin with the exception of untaxed Native Americans. Later, those of African descent were specifically included, and a case in 1870 granted the first citizenship to a Chinese child under the law.

However, Asian immigration would remain an issue for decades afterward, especially on the U.S. West Coast. The situation became grave with the first wave of Chinese immigration in the mid-1800s. In just three years, around 1850, the Chinese population in America grew from just over 300 to more than 20,000 and continued to skyrocket. What were they doing here?

Unrest in China and the growing American economy attracted men to the United States. The gold and silver mines, railroads, agriculture, and fishing industries all saw huge influxes of Chinese. Prejudice, jealousy—and in some cases violence—forced the populations into the so-called “Chinatowns.” The first Chinese Exclusion Act, which was passed in 1882, forbade Chinese immigration to the United States. Interestingly, this law was not repealed until 1943.

This restriction left the growing demands for labor that had been fulfilled by the Chinese in need of another source; Japan developed as that source. This initial clash of ethnicities and economics set the stage for the future conflicts that had a major impact on the next wave of Asian immigrants, the Japanese.

The First Japanese Immigrants

The first Japanese began arriving after the 1868 Meiji Restoration of the Emperor in Japan. Society in the primarily feudal nation was changing and awareness of the outside world growing. The often government-sponsored immigrants headed for Hawaii and the West Coast. This group was especially skilled in intensive agriculture and became a major factor in agriculture on the West Coast. Because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, demand for their labor soared. The immigrants were called “Issei” and their offspring, the “Nisei,” were American citizens. Additionally, Nisei who studied in Japan were termed “Kibei.”

Japanese American productivity astonished other Americans. The Commission’s report on the incarceration states, “The skills of the Issei as intensive farmers were rewarded. In 1917, for example, the average production per acre among all California farmers was less than $42; for the average Issei it was $141.” Within a few years the Issei were perceived as an economic threat by West Coast farmers, labor unions, and nativist interest groups. The same pattern of isolation as seen with the Chinese began to develop.

The program to remove the Japanese from “white” society began with San Francisco schools being segregated in the early 1900s. The success of this action forced President Theodore Roosevelt, concerned with U.S.-Japan governmental relations, to promise restrictions on Japanese immigration if the segregation plans were reversed. This was agreed to, and the first “Gentleman’s Agreement” restricting Japanese immigration to “merchants, ministers, leisure travelers, and students,” was formalized in 1907.

However, as with most situations driven by economically fueled racial attacks, this was not enough to satisfy the anti-Japanese lobby. Soon California passed the Alien Land Act, which basically forbade those who could not be citizens from owning land. The isolating and humiliating aspects of this action are not hard to imagine.

Weak Political Power of the Japanese Minority

The resentment against the Japanese American population continued throughout the early 20th century. It culminated in the 1924 National Origins Act, which, through its provisions regarding quotas, virtually ended Japanese immigration. This law and the general treatment of the Japanese in America became a flashpoint between the two governments and was a significant element of the Japanese resentment that would eventually lead to war in 1941.

The continuous attacks on the Japanese caused the group, to a large degree, to draw in on itself. There were outward expressions of patriotism for the United Staes, but celebrations of Japanese culture were often common. Viewed from the hostile “white” perspective, this only fed the prejudice against and isolation of the group. However, the Issei and Nisei did view themselves as Americans and generally rejected the racial fascism developing in Japan. They were truly caught between cultures.

Accompanying this was the dependency forced on Japanese Americans by the land acts. They could and would protest and try legal means to redress their situation, but only to a certain degree. The “white” landowners needed them to work the land, and the Japanese Americans needed the work. If they forced the issue politically, the backlash might be economically devastating. Therefore, the protest against the status quo was perhaps less than might have been expected.

The last factor to consider before 1941 was the size of the Japanese American population in the United States in the 1940 census—approximately 127,000, down from a high of 139,000 in the 1930 census. Interestingly, the negative situation in the United States fed a diaspora of Japanese—not only to their homeland, but to other nations, such as Brazil, which would greatly benefit from their arrival.

However, the significant fact is the size of the Japanese American population. At 127,000, this was a small percentage of the total population with almost no political influence in the State of California or indeed the nation. Japanese American political power was perhaps the weakest of any major ethnic group in the United States. This is especially true when compared to the size and political power of the millions of immigrants or citizens of Italian and German descent. These two nationalities, along with the Japanese, would move to the center stage of national suspicion after December 7, 1941.

Anger and Fear

As horrified Americans learned of the attack and subsequent destruction at Pearl Harbor, two violent emotions engulfed the nation. The first was a powerful, unifying hatred of the Japanese and their “treacherous” methods used in the attack, fueling an overwhelming desire for revenge. The second emotion was fear.

These emotions propelled the country’s military and industrial capability to a point where it waged war on two fronts and still provided vast amount of war supplies to its allies. The incredible response of the nation’s industrial sector ensured the future defeat of Japan, Germany, and Italy. In one moment the country’s divisive, isolationist lobbies were thrown aside in an eruption of anger that was little anticipated.

Congress roared its approval of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s speech declaring war. Only weeks before, a tedious internal wrangle would have met any attempt to even consider such a resolution. This translated into an almost instantaneous mobilization of young men for the armed forces and civilians in industry. The sleeping giant had been rudely awakened and was very, very angry.

Perhaps one statistic can highlight what this meant in fighting the war in the Pacific, which the Japanese had so aggressively unleashed. By 1945, the U.S. Navy, then the largest in the world, would be 8.5 times larger than it was it 1941. Conversely, Japan’s navy littered the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

Fear gripped America’s West Coast in 1941. With the damage inflicted on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, no longer did the public look out at the Pacific and see a wall of steel between the mainland and the rampaging Japanese. Now many saw a highway wide open to these new enemies.

Fear of Espionage in America

In America, these fears reached a fever pitch as the Japanese recorded one victory after another. December 1941 was dark indeed. Pearl Harbor was attacked, and Wake Island, Guam, and Hong Kong all fell. In January and February 1942, it got worse. The battle for the Philippines raged with little hope—and no relief for the American and Philippine forces.

Numerous British and Dutch colonies fell, including the major British base at Singapore. Japanese atrocities against both uniformed forces and civilians were reported. Darwin, Australia, was attacked from the air. The combined Allied navies were ignominiously defeated at the Battle of the Java Sea. The crescendo of Allied defeat and Japanese success was a roar in the minds of Americans.

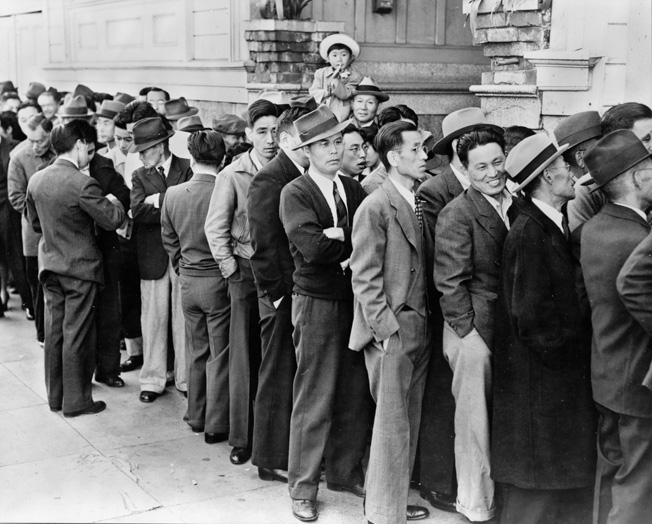

San Francisco, California, watched over by a single armed U.S. solder, wait to register for government-mandated forced relocation, April 1942.

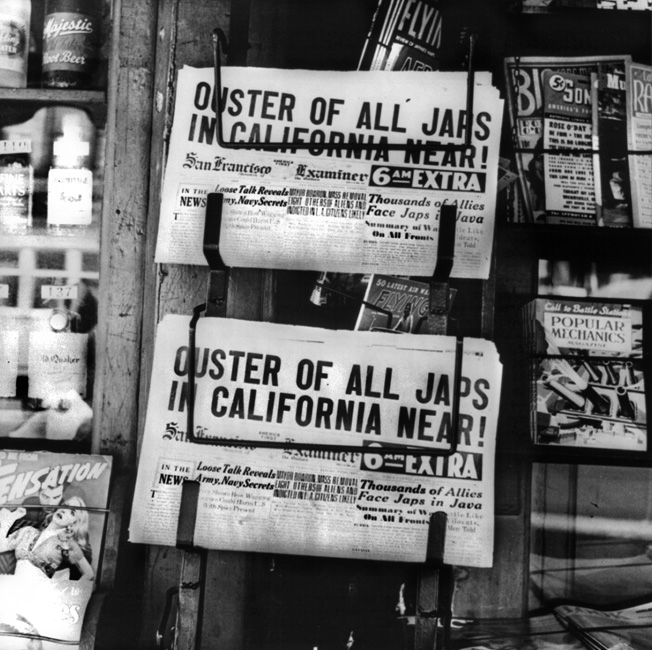

To add to this, newspapers such as the Los Angeles Times trumpeted headlines further escalating the fear factor, such as: “SUICIDE REVEALS SPY RING HERE: Japanese Doctor Who Killed Self After Arrest Called Espionage Chief” (December 19, 1941); “WHAT TO DO IN CASE OF POISON GAS ATTACKS” (December 19, 1941); “JAP SUBS RAID CALIFORNIA SHIPS: Two Steamers Under Fire” (December 21, 1941); “JAPAN PICTURED AS A NATION OF SPIES: Veteran Far Eastern Correspondent Tells About Mentality of Our Enemies in Orient” (December 23, 1941); “[U.S.] REPRESENTATIVE FORD WANTS ALL COAST JAPS IN CAMPS” (January 22, 1942); “NEW WEST COAST RAIDS FEARED: Unidentified Flares and Blinker Lights Ashore Worry Naval Officials” (January 25, 1942); “OLSEN SAYS WAR MAY HIT STATE: Shift of Combat to California Possible, Governor Declares” (January 26, 1942); “EVICTION OF JAP ALIENS SOUGHT: Immediate Removal of Nipponese Near Harbor and Defense Areas Urged by Southland Officials” (January 28, 1942).

Note the linkage in the press between questionable events and the need to do something about the local Japanese. By February 1942, this hysteria led directly to Draconian measures against Japanese Americans. With the signing of Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, by President Roosevelt, Issei, as registered aliens, and Nisei, who were citizens, were forced to relocate to some of the harshest and most remote areas of the American West.

Some authors have attempted to portray the Pacific War as a purely racial one. This author disagrees with that conclusion, but there is no question that racial prejudice, fed by ignorance on both sides, was an important underlying element in the feelings expressed by either population. Given the fear levels on the West Coast, the ability of U.S. whites to visually isolate Japanese Americans was a significant factor.

John DeWitt: Driving Force For Japanese Internment

The drive for the removal of the Japanese Americans on the West Coast was led by General John L. DeWitt—a career Army officer characterized by the Carter Commission as “not an analyst or careful thinker who sought balanced judgments of the risks before him.” DeWitt wanted the Japanese out of his region, the Western Defense Command, as soon as possible. His declared motive was a concern over the sabotage and espionage potential of this ethnically Japanese population. As early as January 1942, he was petitioning the War Department and other government agencies for permission to do this.

DeWitt envisioned a system of assembly areas where the impacted individuals would be collected and sent to guarded relocation camps. There was some discussion of simply dispersing the population inland, but the receiving states would have none of that; they feared that these “dangerous” persons would sabotage their sensitive defense areas.

All of this structure would shortly be in place. However, the executive order making it possible had to be signed, and a fairly significant internal argument developed within the government over the validity of the process and proposed subsequent actions. Because of the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, most civilian government agencies were willing to defer to the military in such matters.

However, the Justice Department under Attorney General Francis Biddle became a significant stumbling block for DeWitt and others interested in wholesale removal. Additionally, the War Department itself remained neutral until pushed. President Roosevelt seemed supportive of the concept of removal but disinterested, conceivably with more important matters on his mind.

“Military Necessity”

The primary justification for the removal of registered aliens and citizens without any establishment of their individual potential threat was deemed a “military necessity” by DeWitt and others. One can only speculate if the Pearl Harbor investigative committee’s severe handling of the Pearl Harbor commanders, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel and General Walter C. Short, had any bearing on his attitude. However, DeWitt’s attitude was openly hostile to Japanese Americans. Indeed, it is questionable whether he even recognized the Nisei as citizens.

When DeWitt was questioned in 1943 by Representative George J. Bates of Massachusetts, the following exchange ensued:

“Gen. DeWitt: I have the mission of defending this coast and securing vital installations. The danger of the Japanese was, and is now—if they are permitted to come back—espionage and sabotage. It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen; he is still a Japanese. American citizenship does not necessarily determine loyalty.

“Mr. Bates: You draw a distinction, then, between Japanese and Italians and Germans? We have a great number of Italians and Germans and we think they are fine citizens. There may be exceptions.

“Gen. DeWitt: You needn’t worry about the Italians at all, except in certain cases. Also, the same for the Germans, except in individual cases. But we must worry about the Japanese all the time until he is wiped off the map. Sabotage and espionage will make problems as long as he is allowed in this area—problems which I don’t want to have to worry about.”

Opposition to DeWitt

Clearly DeWitt was predisposed to judge the Japanese Americans en masse and not as individuals. This was directly opposed to the Justice Department’s view. Surprisingly, the intelligence services employed on the issue at the time agreed with the Justice Department. Both the Office of Naval Intelligence and the FBI conducted extensive investigations and found no reason for either worry about the population or evidence of actual espionage and sabotage.

It was clear that Hawaii had experienced Japanese espionage before the attack, but this was deemed to be centered on professional agents rather than the general population. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover repeatedly reported that the Japanese American population should not be regarded as a mass or major threat. In fact, the FBI had compiled lists of those to be either questioned or arrested in the event of war—lists that included approximately 2,200 Japanese, 1,400 Germans, and 300 Italians. They had all been rounded up by February 1942, and the agencies were satisfied that they had eliminated the majority of the potential problems.

It must be reiterated and understood that there was not a single example of sabotage or espionage from the Japanese American population during the entire war. However, the facts were not permitted to interfere with actions desired by strong lobbies primarily in California and the other West Coast states and in some parts of the federal government.

Swaying Public Opinion

Besides DeWitt and the California press, two other sources surfaced that had major influence on public opinion and which would directly impact the signing of the executive order.

One of the most destructive forces to a reasoned approach to this issue came from Secretary of the Navy Henry Knox. Upon returning from a tour of Pearl Harbor after the attack, he started agitating about Japanese espionage and sabotage. As quoted in the Commission’s study, he declared, “I think the most effective Fifth Column [subversive] work of the entire war was done in Hawaii, with the possible exception of Norway.”

With the words “Fifth Column,” he put the Japanese American community in the sights of groups ready to see it removed and influenced all Americans to support this concept. Of course, there were no such events occurring during the attack and none were mentioned in his later official report on the attack on Pearl Harbor. However, the damage was done. This was a high government official openly talking of a substantive threat to the United States from its own citizens and legally residing aliens.

Groups such as the American Legion and the Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West pushed for removal. Those with economic interests hid behind patriotism or the racist stereotyping of the day. They were, in turn, supported by various California politicians and Congressional representatives. The furor in the press, too, was unabated, and no amount of rational discussion could stop the hysterical cry for removal.

Attorney General Biddle was fighting a valiant fight but was slowly losing to the proponents of relocation. Secretary of War Stimson was still neutral, but eventually the political pressure was too much. The pressure increased as the whole West Coast Congressional delegation sent a letter authored by their senior member to Roosevelt demanding removal of all ethnic Japanese. Roosevelt could not be bothered to meet with Stimson on the subject, although he did lunch with Biddle to discuss the issue.

The silence from Washington, D.C., could not continue. Indeed, such national figures as political commentator Walter Lippman and, believe it or not, Dr. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel) came out with opinions and, in Seuss’s case, a cartoon depicting Japanese Americans as a threat.

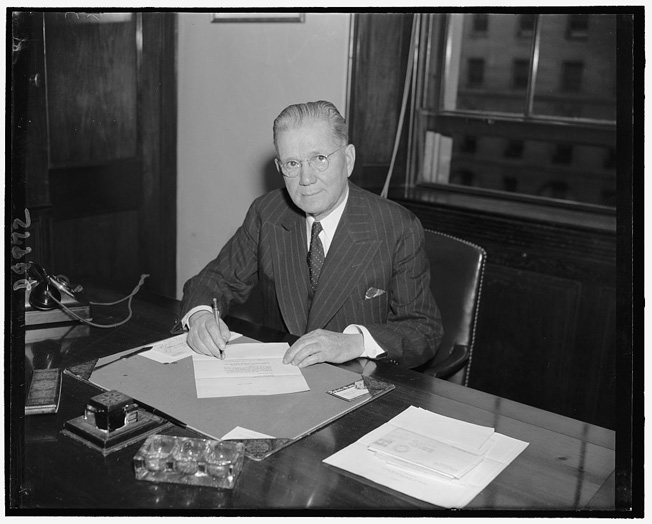

Stimson’s Decision

Finally, a phone call between Stimson and the president left the decision in Stimson’s hands. His leanings became a pronounced preference for removal, even though he feared “this will make a tremendous hole in our constitutional system….” Following his discussion with the president, Stimson and Biddle began drafting the order as Biddle deferred to the senior cabinet member and, in essence, the military. There were some major staff dissensions from both agencies, but the logjam had been broken and events moved quickly. On February 19, 1942, the order was signed.

Amazingly, the order does not mention any ethnicity, but it was well understood that it applied only to Japanese in the United States. The important and operational phrase was “direct the Secretary of War, and the Military Commanders … to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion.”

A Congressional investigative committee—the Tolan Committee, headed by John Tolan, a representative from California—traveled in February 1942 to the West Coast just after the release of the executive order to hear evidence that was largely damning of the Japanese American population and supportive of removal and incarceration. This “official” report released in May 1942 only added to the furor.

The die was cast, and events took on an avalanche-like quality and would certainly be received as an avalanche of woe by the Japanese American community.

Selective Enforcement of Internment

Before looking at the expulsion of the Japanese American population and establishment and life in the camps, there are several concurrent events that should be discussed. The first is why equal action was not taken against German or Italian Americans or those of Japanese descent residing in Hawaii. Each case was different, but the first and most direct answer is that there were too many of them.

There were over one million Axis nationals living in the United States. There were also millions of citizens of German and Italian descent, and the unfair treatment of Germans in the United States during World War I was fresh in the minds of many government officials and the public.

Additionally, the political and economic clout of these groups was immense. One need only envision the reaction of citizens of Italian or German heritage, such as New York mayor and decorated WWI flier Fiorello LaGuardia or perhaps baseball’s famed DiMaggio brothers, whose parents were immigrants, to see the point.

Of course, there were fascist sympathizers, both American and foreign nationals, among the population, and the more dangerous ones were likely on the FBI’s list. Besides arrests, some individuals were excluded from sensitive military areas. After war was declared, organizations like the pro-Nazi Bund and pro-Mussolini FLNA simply disappeared.

The Hawaiian situation was different again. After Pearl Harbor it could be argued that Hawaii was the most controlled area in the United States. Martial law had been imposed soon after the attack with habeas corpus suspended and under much stricter conditions than anything imposed on the mainland. There were consequent restrictions on all Japanese, German, and Italian aliens there and on the mainland. There were also spot restrictions on any ethnic Japanese from portions of the islands.

Also, limits on travel, curfews, ownership of weapons or radios, and other measures were imposed. Gradually, other Japanese Americans came under increasing isolation. Japanese Americans were forced out of the Hawaiian Territorial Guard, despite the fact that they had performed well on December 7. The 2,000 or so Nisei in Army regiments were isolated into one unit. Ironically, this later formed the core of the first Nisei combat unit, the 100th Infantry Battalion.

Forced Removals From Hawaii and the Aleutians

Secretary Knox was vehement on the issue of removal of Japanese Americans from Hawaii to the mainland. He obtained Roosevelt’s support, and immense pressure was put on Lt. Gen. Delos C. Emmons, the military governor of Hawaii, to comply. Emmons saw no need for evacuation and dragged his feet as long as he could, but by spring 1942 he was ordered to take action.

Approximately 2,000 Hawaiians of Japanese ancestry (from a population of 158,000) were sent to the mainland, but by the following year the program was largely suspended; the first evacuees returned in 1945.

Once again, sheer numbers had triumphed, with those of Japanese descent comprising over a third of Hawaii’s population. This was too large an economic force to disrupt, and the logistics of moving them across the Pacific would have been extremely complex. There were also positive factors such as the military’s rational view of the situation starting with General Emmons and the much more positive race relations in the diverse island community.

The other forced removal in the United States was of the native Aleuts from the Aleutian Islands. The islands became an active war zone in June 1942, and the population of approximately 900 was removed for its own safety. However, the results were devastating to the Aleut people and culture. The mortality rate among the island elders was extremely high, a factor that led to an erosion of this unique culture.

Also, the property they left behind was either purposefully destroyed to prevent use by the enemy, vandalized, or “borrowed” by both armies (the Japanese invaded the islands of Attu and Kiska; U.S. forces retook the islands in 1943), leaving destruction of their meager physical plant in its wake. Although allowed to return in 1944, little was done to assist the natives and no reparations were paid until the 1980s, and then only at a very low level. The destruction of this proud and unique group of people was a sad result of saving the only occupied U.S. territory of the war located in the Western Hemisphere.

Forced Removal of Ethnic Japanese Outside of the U.S.

Finally, in addition to the United States, other countries forcibly removed ethnic Japanese, among them Australia, New Zealand, and Peru, along with other Latin American nations. Perhaps the example closest to home for Americans was their neighbor to the north, Canada.

Initially, the Canadian government tried removing just males, but this solution would not satisfy those pushing for complete removal; many of the same forces of racism and economic interest found in the United States were present in Canada. Another reason more prominent in Canada, although a minor concern in the United States, was the possibility of the white population turning against the Japanese. Whether real or imagined, this factor led to expulsion of all ethnic Japanese from a band extending inland 100 miles from the West Coast.

Over 20,000 Japanese Canadians were removed from their homes and placed in camps similar to those in the United States. However, unlike in the United States, they were dispossessed of their property, which was sold to offset the costs of the removal. Additionally, they were stripped of their citizenship and civil rights. To add salt to the wound, they were faced with a choice of either emigrating to a demolished Japan or moving to eastern Canada. Under international and internal pressure, the expulsions were halted—but not until 1947; their civil rights and citizenship were returned in 1949. When the United States approved compensation in 1988 for the victims of the removal, Canada did the same.

The War Relocation Authority

With the order signed, implementation was the next action. On March 18, 1942, the War Relocation Authority (WRA) was established to handle the removal. Headed by Milton Eisenhower, the WRA was designated as part of the Executive Branch.

General DeWitt, meanwhile, established the military areas called for in the executive order. Military Area 1 ran from the coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington inland to approximately half the width of each of these states and was to be emptied of all enemy aliens, Japanese, German, and Italian, in that order. However, while the term “alien” was correctly applied to those of European descent, in DeWitt’s view all Japanese, whether Issei or Nisei, were aliens.

Military Area 2 was the rest of the area of the three states. Aliens could settle in this area, but with restrictions. Initially, the Japanese community was encouraged to voluntarily relocate, and some small groups did so to avoid the camps, but the economics of such a move were punishing. They had to leave everything behind and had no prospect of home or employment in the areas they chose for relocation. Almost unbelievably, “Asian-appearing” children of some Anglo parents were separated from their parents and sent into the camps alone.

Some persons decidedly hostile toward Japanese Americans welcomed their removal, some going so far as to publicly hang signs and banners on their homes and businesses expressing their antipathy toward those citizens and telling them they were not welcome in their communities.

Opening the Internment Camps

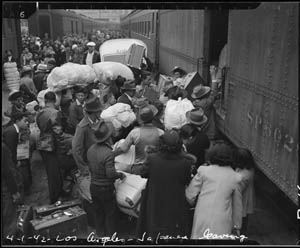

On March 31, 1942, the movement began. Eventually, 15 assembly areas and 10 relocation camps were established. Three of the assembly areas were located in Washington, Oregon, and Arizona. All the rest were in California, while the relocation camps were scattered from California to Arkansas.

The first camp to open was Manzanar in California about 90 miles east of Fresno, and the others followed apace. The camps were administered by the WRA. Additionally, there were four Justice Department Internment Camps intended for those suspected of being enemy agents and two Citizen Isolation Camps for troublemakers.

The “INSTRUCTIONS TO ALL PERSONS OF JAPANESE ANCESTRY LIVING IN THE FOLLOWING AREA” issued by DeWitt must have been harrowing in their starkness. An excerpt regarding what to bring and the disposition of the balance of personal property reads: “2. Evacuees must carry with them on departure for the Assembly Center, the following property: (a) Bedding and linens (no mattress) for each member of the family; (b) Toilet articles for each member of the family; (c) Extra clothing for each member of the family; (d) Sufficient knives, forks, spoons, plates, bowls and cups for each member of the family; (e) Essential personal effects for each member of the family.

“All items carried will be securely packaged, tied and plainly marked with the name of the owner and numbered in accordance with instructions obtained at the Civil Control Station. The size and number of packages is limited to that which can be carried by the individual or family group.

“3. No pets of any kind will be permitted.

“4. No personal items and no household goods will be shipped to the Assembly Center.

“5. The United States Government through its agencies will provide for the storage at the sole risk of the owner of the more substantial household items, such as iceboxes, washing machines, pianos and other heavy furniture. Cooking utensils and other small items will be accepted for storage if crated, packed and plainly marked with the name and address of the owner. Only one name and address will be used by a given family.”

Conditions of the Camps

The assembly areas were chaotic and primitive, the process haphazard at best, and subject to the whim of the local WRA administrators. Many in the assembly areas looked forward to their assignment to a relocation camp where, conceivably, conditions would be better. They were usually disappointed. Whether located in a swampy portion of Arkansas or a high western desert, the locations were terrible, with extremes of cold and heat. Severe winds bringing dust were a common factor in the western camps, isolated and ringed with barbed-wire fences and armed guards—not unlike Nazi concentration camps in appearance. The experience was crushing in spirit for the vast majority of detainees, who saw themselves as proud Americans being unfairly treated.

A typical camp featured poorly constructed wooden barracks approximately 20 by 120 feet, which were generally not insulated; as the exterior wood dried, gaps appeared in the walls. Evacuees would try desperately to seal these against dust or cold with newspaper; some barracks were covered by black tar paper, giving them an even more dreary appearance. The barracks were divided into four or six family units, and there was water only in the communal areas. The sanitary facilities were also communal and segregated by sex.

Food was provided, as was health care, but with a war on both left a lot to be desired. However, through all of this many held onto their positive spirit and would improve the facilities, providing their own high standard of dignity. In the words of one detainee, “When we entered camp, it was a barren desert. When we left camp, it was a garden that had been built up without tools, it was green around the camp with vegetation, flowers, and also with artificial lakes, and that’s how we left it.”

Accounts of the Camps

All of the statements that follow and more are found in the Commission’s report.

A U.S. Army guard assigned to Santa Anita, California, reported, “We were put on full alert one day, issued full belts of live ammunition, and went to Santa Anita Race Track…. There we formed part of a cordon of troops leading into the grounds; buses kept on arriving and many people walked along … many weeping or simply dazed, or bewildered by our formidable ranks.”

One detainee, Monica Sone, said, “[W]e were given a rousing welcome by a dust storm…. We felt as if we were standing in a gigantic sand-mixing machine as the 60-mile gale lifted the loose earth up into the sky, obliterating everything. Sand filled our mouths and nostrils and stung our faces and hands like a thousand darting needles. Henry and Father pushed on ahead while Mother, Sumi and I followed, hanging onto their jackets, banging suitcases into each other. At last we staggered into our room, gasping and blinded.”

Another said, “Camp life was highly regimented and it was rushing to the wash basin to beat the other groups, rushing to the mess hall for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. When a human being is placed in captivity, survival is the key. We developed a very negative attitude toward authority. We spent countless hours to defy or beat the system. Our minds started to function like any POW or convicted criminal.”

Another detainee reported, “To a friend who became engaged, we gave nails—many of them bent—precious nails preserved in fruit wrappings, snitched from our fathers’ meager supply or found by sifting through the sand in the windbreak where scrap lumber was piled.”

The WRA itself reported, “With no exceptions, schools at the centers opened in unpartitioned barracks meant for other purposes and generally bare of furniture. Sometimes the teacher had a desk and chair; more often she had only a chair. In the first few weeks many of the children had no desks or chairs and for the most part were obliged to sit on the floor—or stand up all day. Linoleum laying and additional wall insulation were accomplished in these makeshift schoolrooms some time after the opening of school. At some centers cold waves struck before winterization could be started.”

The Cost of Internment

The physical and psychological hardships from this treatment were immense. However, one significant hardship would form the basis for some redress of these injustices. The economic losses of the group were significant and very deep. This occurred because of their unique, isolated cultural situation. It must not be forgotten that the whole population was removed. In a community such as the Japanese American one, this generally meant everyone a family knew. Either through racist and economic isolation by whites or their own turning inward against this treatment, the results of this isolation were appalling, magnifying the human cost of removal.

Given as little as four days—or the lucky ones given two weeks to dispose of all of their property except what they could carry or store—the results were a boon for those preying on the group. The U.S. government would take into storage their furniture, appliances, etc., but in many cases these goods went missing or were vandalized during the war. Vehicles were sold at rock bottom prices as there were only days to sell them. When all of one’s friends and family were in the same situation, there were few to turn to for a fair deal.

The worst happened in the case of their homes or land, sold for pennies on the dollar. Tenant farmers lost their rights and income when sent inland, and entire generations of a family were financially wiped out. In his detailed and extremely well researched A Tragedy of Democracy, Greg Robinson cited the damage done as between “67 and 116 million dollars [1945 dollars].” These conditions existed in all three states impacted by the evacuation order. Only in 1948 would the government begin to address this issue, however insufficiently and slowly.

The Loyalty Questionnaire

The evacuees who had not had any hearings or other means of establishing their loyalty were now faced with one more terribly divisive test of their spirits. However, this same test would see the formation of Japanese American combat units that would forever end discussion of their loyalty or absolute value as Americans.

The camps had become hotbeds of the very feelings against the government they had been established to remedy. Morale in the camps was poor at best. To try and improve the situation regarding the lack of legal process impacting the detainees and indeed provide for a means of “leave” from the camps, the government instituted a loyalty questionnaire in February 1943. This would provide the basis for enlistment in the armed forces or work in a defense plant, agriculture, or other pursuit, but it was poorly conceived and executed.

Forced on the detainees with little explanation and no real thought as to the consequences, the loyalty questionnaire would, in general, make a bad situation worse. Some detainees were afraid of being turned out with no possessions. Others wondered how this would impact the ability to be compensated for the relocation. Much doubt and confusion ensued.

Frank Kageta, an internee quoted in the Commission report, described his experience at Tule Lake, California, the largest and possibly most troubled of the camps: “The most tragic, as well as traumatic, event that happened during my stay in Tule Lake that still remains with me is the questionnaire with the loyalty oath that was required of all of us to answer. I have never even mentioned this to my children.”

The “No-No Boys”

The specific questions that would radically split the community were numbers 27 and 28. The questions basically asked, “Are you willing to serve in the U.S. Armed Forces and swear ‘unqualified’ allegiance to the U.S.?” The answers to these questions would be radically impacted by camp experience. The mood in the camps was angry and getting worse. At Tule Lake and Manzanar there were violent incidents.

Now insult was added to the injustice of confinement and, especially for the Nisei, American citizens, this was the final straw. Those who responded “no” to the questions became known as the “no-no boys” and were treated as hostile to the United States. In many cases they were only hostile to the treatment they had received.

A group detained at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, urged draft resistance based on their feelings about incarceration. Their sentiments go a long way toward explaining the rise of the “no-no boys” and more violent protests in the camps. Quoted in Greg Robinson’s book, their feelings are simple and clear: “We, the members of the FPC (Fair Play Committee) are not afraid to go to war—we are not afraid to risk our lives for our country. We would gladly sacrifice our lives to protect and uphold the principles and ideals of our country as set forth in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, for on its inviolability depends the freedom, liberty, justice and protection of all people including Japanese Americans and all other minority groups. But have we been given such freedom, such liberty, such justice, such protection? NO!!”

Support For the Evacuees

Protests by both Japanese Americans and concerned white Americans continued to grow during 1942. They were met by strong opposition. The country was clearly divided and generally supported the exclusion. Initially, the Japanese American response from their organized groups was confused between loyalty to the United States and a strong sense that something was wrong. However, some groups and individuals eventually began calls for justice that could not be ignored. Other non-Japanese groups began siding with the evacuees, such as The Friends and the Socialist Party. Interestingly, the Communist Party dismissed its Nisei members, and the national American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) surprisingly supported the government. The tone of support ranged from harsh condemnation of the lack of due process to equally harsh condemnation of the camps’ conditions. The Red Cross began making inspections, which helped to some degree.

The only governor to invite evacuees to his state, Ralph Lawrence Carr of Colorado, would suffer in the next election for his humane stance. However, Camp Amache at Granada, in dry, dusty southeast Colorado, remained one of the better run camps for its term of occupation. Politically, members of the U.S. administration began to side with those incarcerated, questioning the motive and supposed needs that drove the treatment. These included Attorney General Biddle, wading back into the fray during late 1943, and Harold Ickes, Secretary of the Interior, along with other influential military men and politicians. This support from outside their community brought to national attention both the legal and human elements of the evacuee story.

Of course, opinion in the Anglo community on the West Coast was generally still virulently in favor of removal. Earl Warren, then Attorney General of California, did not distinguish himself with his testimony to the Tolan Committee when he stated, after a review of where the Japanese American population lived in California, “Such a distribution of the Japanese population appears to manifest something more than coincidence. But, in any case, it is certainly evident that the Japanese population of California is, as a whole, ideally situated, with reference to points of strategic importance, to carry into execution a tremendous program of sabotage on a mass scale should any considerable number of them be inclined to do so.”

Court Cases on Internment

However, legal assaults on this mass conviction without due process began to gain ground. Four cases were extremely important in questioning the policy of Executive Order 9066 and were appealed to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court did not cover itself with glory. In fact, it waited until after the 1944 elections and the subsequent withdrawal of the evacuation order to rule on the case most positive for the Japanese Americans.

The first three cases involved Japanese American citizens who had resisted incarceration or violated curfew laws. These were Hirabayashi v. United States, Yasui v. United States, and Korematsu v. United States. Interestingly, they were test cases inspired by local or individual ACLU attorneys while the national leadership of the organization would still not challenge the evacuation.

The JACL (Japanese American Citizens League) opposed the cases as questioning the government in time of war, so the individuals were basically on their own and showed great courage in proceeding. In all cases there was evidence of government tampering with documentation and making misstatements that were not significantly questioned by the court. Like the early push for removal and incarceration, the civil government was deferring to the military.

In these cases, the court ruled on minor matters while sidestepping the major issues. In Yasui and Hirabayashi, the process of exclusion based on race was supported. In Korematsu, the general tone supported the executive order. There was strong division in the court in all cases, with significant dissenting opinions.

However, in Ex Parte Endo, a fourth case pursued by an especially valiant woman, the court found that, “The War Relocation Authority, whose power over persons evacuated from military areas derives from Executive Order No. 9066, which was ratified and confirmed by the Act of March 21, 1942, was without authority, express or implied, to subject to its leave procedure a concededly loyal and law-abiding citizen of the United States.” However, as in Korematsu, this ruling was made after the 1944 election and the subsequent decision to end the exclusion.

Unrest in the Camps

The year 1943 saw extreme unrest and political action in the camps. The Fair Play Committee valiantly opposed the draft in pursuit of its civil rights. At Tule Lake and Poston War Relocation Camp, Arizona, on the California border there were further violent incidents against the camp administration and, in some cases, against loyal detainees by those with Japanese sympathies. Over 5,700 Japanese Americans eventually renounced their citizenship to protest their incarceration, and 95 percent of these were located at Tule Lake.

At the same time, the government realized it had to find an orderly way to return these citizens to normal life but was wrestling with the image of the military, legal issues, and fear of racial violence if the Japanese Americans were settled in hostile areas. Traditional family structure was breaking down in the camps, and morale was almost below any possible measure. Several inmates had been shot by guards under suspicious circumstances.

The times were bleak.

The treatment of Japanese-Americans was patently racist and everyone knows that now as well as most did then. The flip side is the treatment of American and European nationals by the Japanese when they overran the Philippines, Hong Kong, Singapore and the Dutch East Indies. The conditions were near starvation, little medical attention, summary punishments to include executions, and a level of cruelty and neglect exceeded only by the Nazi’s in German occupied Europe. My late wife’s family knew more than most what was in store for them and fled into the Philippine jungle where they survived for almost three years. While the US government made some efforts at compensation to the Japanese internees, few in Asia saw any from the Japanese government.

As an Asian American and Japanese American myself, your comment highlights the realization that I would have never been “American” enough to be treated fairly at that time because, in light of also being Japanese, these were grounds for them to do what they did. Your comment says “most knew it was racist at the time” and yet if they did, they shouldn’t have allowed it to happen. Japanese Americans were not responsible for the actions of the Japanese government so I don’t understand your attempt to connect Americans making minimal effort and the Japanese government not making minimal effort as being reason enough why Americas actions towards Asian Americans as being remotely justified. It just minimizes the harm and excuses them from any accountability.

Your example is not comparable. The Japanese invasion of the Philippines was a foreign army invading a sovereign nation. What the US did, was to its own citizens, without justification, except for racism. It was inadequately addressed much later and instead of trying to use it as a teaching moment to prevent it from happening again, the issue has been glossed over. Definite breach of constitutional rights.

Both of you please note that I did not cite any American practice as justification based on Japanese actions. It did not become fully apparent how poorly the Japanese treated internees until after the war. I could just have easily cited the American internment of Italian-Americans or German-Americans, not as large numbers as Japanese-Americans and not as well known, but real.

Thank you for highlighting this part of our american history. Thank you for fair equal treatment to the facts. The article is very detailed and comprehensive and illustrates the rationale at the time, and the suffering caused by the xenophoia of the past.