By Brent Douglas Dyck

Former German President Horst Koehler once said that Auschwitz, the largest Nazi extermination camp, was home to the “worst crime in human history.”

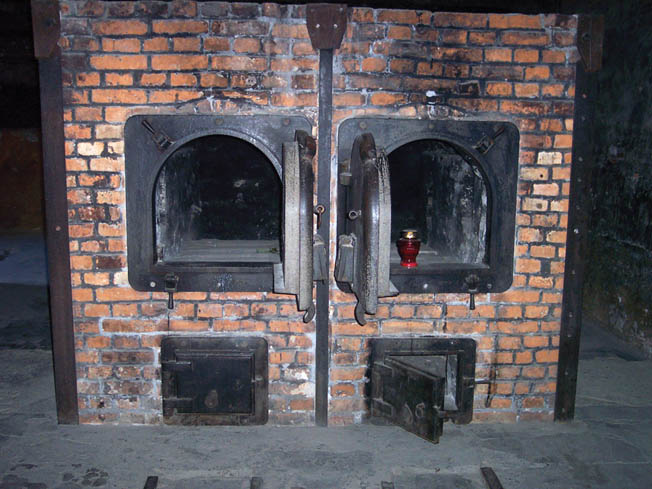

Rudolf Hoess, the commandant of Auschwitz, confessed during his trial after World War II that approximately 1.1 million prisoners, mostly Jews, had been killed at Auschwitz by Hitler’s SS over a 41/2-year period. Some historians believe that the death toll may have been much higher. Most of these victims were killed in gas chambers, their bodies burned in crematoria, and their ashes dumped in a nearby marsh.

Many historians have wondered ever since, “Why wasn’t Auschwitz bombed by the Allies?” This is one of the most controversial and hotly debated topics among historians who study World War II. Did the Allies know about Auschwitz? If so, could it have been bombed or was it too far away? Would bombing Auschwitz have taken away from the war effort? Lastly, if it was possible, would it have been effective or would it have done more harm than good?

In considering the feasibility of bombing Auschwitz, one needs to know if the Western governments knew about the world’s largest killing center. The answer is a definitive yes. As historian Tami Davis Biddle has discovered, the first report about Auschwitz was made as early as January 1941—only six months after it had opened and before the gas chambers were installed. A report from the Polish underground was sent to the Polish government in exile in London, where it was forwarded on to Sir Charles Portal, the chief of the British Royal Air Force. The report said Auschwitz was one of the Nazis’ “worst orgainized (sic) and most inhuman concentration camps.”

In November 1942, the Polish underground reported to the Polish government in London that tens of thousands of Jews and Soviet POWs were shipped to Auschwitz “for the sole purpose of their immediate extermination in gas chambers.”

The American public was first introduced to the horrors of Auschwitz on November 25, 1942, when the New York Times published an article on page 10 that stated, “Trainloads of adults and children [are] taken to great crematoriums at Oswiencim [Auschwitz], near Cracow.” In March 1943, the Directorate of Civilian Resistance in Poland reported that 3,000 people a day were being burned in a new crematorium at Auschwitz.

Another report, from a Polish agent codenamed Wanda, was given to the American military attaché in London in January 1944. She claimed, “Children and women are put into cars and lorries and taken to the gas chamber…. There they are suffocated with the most horrible suffering lasting ten to fifteen minutes…. At present, three large crematoria have been erected in Birkenau-Brzezinka for 10,000 people daily which are ceaselessly cremating bodies.”

On March 21, 1944, the Polish Ministry of Information released a report to the Associated Press that “more than 500,000 persons, mostly Jews, had been put to death at a concentration camp” at Auschwitz. The report stated that most had been killed in gas chambers “but since the supply of gas was limited some persons are not dead when they are thrown into the crematorium.” The story was printed in both the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post.

In April 1944, two men, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, managed to escape from Auschwitz. They in turn gave a detailed report of the camp, including maps and locations of the gas chambers and crematoria, to the Slovakian government. The report was forwarded to British intelligence, and its contents were broadcast over BBC radio in June 1944.

It was also discovered after the war that by the time Auschwitz had been liberated the Allies had photographed the camp at least 30 times during the course of the war. The photos, taken by the U.S. Army Air Forces, were stored at the Mediterranean Allied Photo Reconnaissance Wing in Italy, which was commanded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s son, Colonel Elliott Roosevelt. Some photos even showed inmates being marched to the gas chambers.

Were the Allies capable of bombing Auschwitz?

Once again, the answer is yes. In November 1943, the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) created the Fifteenth Air Force based in Foggia, Italy. Auschwitz, which was 625 miles away in southwestern Poland, was finally within range of American Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and Consolidated B-24 Liberator heavy bombers.

By May 1944, the USAAF had begun attacking the Third Reich’s synthetic oil plants located in Germany, Poland, and Romania. The goal was to bring Hitler’s war machine to a halt. On August 8, 1944, a raid numbering 55 bombers from the U.S. Eighth Air Force flew from airfields in the Soviet Union and dropped more than 100 tons of bombs on an oil refinery at Trzebinia, which was approximately 20 miles northeast of Auschwitz.

Two weeks later, on August 20, the Fifteenth Air Force attacked the I.G. Farben synthetic fuel refinery at Auschwitz, which was less than seven miles from the gas chambers. On September 13, a raid numbering 94 B-24 bombers dropped 236 tons of bombs again on the oil refinery at Auschwitz. A photo taken during this raid by an American bomber crew actually shows the gas chambers and crematoria underneath the falling 500-pound bombs. This compelling image was created because bomber crews were required to release their bombloads while accounting for airspeed, windage, and distance to the intended target to achieve maximum accuracy.

As historian Rondall Rice has written, “The evidence clearly shows the Fifteenth Air Force’s ability to bomb Auschwitz, in aircraft and in command discretion within the target priorities. By the summer of 1944, the command controlled ample aircraft; those aircraft had sufficient range and payloads necessary for such a mission; and bombing directives allowed commanders flexibility to direct attacks against special targets.”

Would bombing Auschwitz have detracted from the war effort?

In June 1944, John W. Pehle, the executive director of the War Refugee Board, appealed to the U.S. government to bomb the railways leading into Auschwitz. In July, Johan J. Smertenko, the executive vice chairman of the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe, sent a letter to President Roosevelt asking him to bomb the extermination camps, especially the “poison gas chambers of [the] Auschwitz and Birkenau camps.”

manufactured for use in the gas chambers of the Nazi death camp at Auschwitz.

That August, A. Leon Kubowitzki, the head of the rescue department of the World Jewish Congress, asked the U.S. government to destroy the gas chambers “by bombing.”

The U.S government rejected all of these requests to bomb Auschwitz. Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy replied in letters dated July 4 and August 14, “Such an operation could be executed only by the diversion of considerable air support essential to the success of our forces now engaged in decisive operations elsewhere.”

In other words, with the D-Day invasion having occurred at the beginning of June 1944, the United States could not spare any aircraft to bomb Auschwitz as their main goal was to defeat the German Army in France. The U.S government believed that the best way to save the Jewish people being murdered at Auschwitz was to defeat the German Army and force Hitler to surrender.

However, American historian Stuart Erdheim has questioned the validity of McCloy’s assertion. Erdheim believes that the gas chambers and crematoria at Auschwitz could have been destroyed in one strategic strike using 100 planes. Erdheim writes, “Viewed against the backdrop of the Fifteenth AF operations, just how ‘considerable’ would one raid of 80 fighters (half for escort) or 100 bombers (with escort) have been?… With the average number of sorties per day between 500 and 650, one mission of 80 fighter sorties represents one-seventh to one-eighth of one day’s total missions.” As Erdheim concludes, “The scale of such an air attack would not have affected the war effort in any appreciable way.”

Historian Richard G. Davis agrees with Erdheim. He states that the destruction of the extermination facilities at Auschwitz, however, would probably have required “a minimum of four missions of approximately seventy-five effective heavy bomber sorties each.” He states that in both July and August 1944, the American Fifteenth Air Force flew approximately 10,700 heavy bomber sorties per month. Davis writes, “Even if one assumes that the three hundred sorties … would all have come at the direct expense of the Fifteenth’s highest-priority target, the German oil supply, the effort expended on Birkenau would have amounted to about seven percent of that effort.”

Davis concludes that “three hundred sorties and 900 tons of bombs, or even twice that number, would not have been a substantial diversion of this total effort.”

The question then is whether bombing Auschwitz would have taken away from the war effort and thereby prolonged the war. The answer, according to Erdheim and Davis, is an emphatic no.

One of the arguments against bombing Auschwitz is that it would have probably killed many inmates in the process. In essence, the Allies would be just as guilty as the Nazis for killing innocent prisoners. However, many historians feel that an attack on the crematoria at Auschwitz would have been successful and should have been attempted. Using precision bombing to attack a concentration camp would have been difficult, but not impossible. In fact a precedent had been set when the U.S. Eighth Air Force attacked the Gustloff ammunition works located beside the German concentration camp at Buchenwald on August 24, 1944.

According to the Buchenwald report, the attack “completely destroyed” the armaments factory “in one single, well aimed blow.” Even though prisoners were killed in the attack, this was not because of errant bombs but because the prisoners were working in the factory areas and were not allowed to retreat to the safety of the concentration camp. In fact, one prisoner said, “The Allied pilots in particular did all they could in order not to hit prisoners. The high number of prisoners killed is to be charged exclusively against the debit accounts of the Nazi murderers.”

Located in Poland, Auschwitz was the scene of mass extermination on a colossal scale.

At Auschwitz the Nazis employed four gas chambers underneath four crematoria buildings. Two were located in the northwest corner of the camp, and the other two were in the southwest corner. According to Erdheim, very few inmates, if any at all, would have been killed if the U.S. Fifteenth Air Force had decided to bomb the gas chambers. The prisoners did not live anywhere near the crematoria, but instead their barracks were located east of the gas chambers. Therefore, Erdheim states that any misdropped bombs “would not result in bombs falling in the barracks area, but rather in: (1) open fields north or south of the crematoria; (2) the second crematoria of each group; and (3) the ‘Canada’ loot storehouse area between the two pairs of crematoria.”

Erdheim also believes that since many of the prisoners were used as forced labor outside of the camp and far away from the crematoria, the chance of killing innocent prisoners was lessened even more.

Rondall Rice writes that if the Fifteenth Air Force had used “a three-bomber front under clear weather, with each bombardier acquiring the target … and in view of the Fifteenth Air Force’s bombing accuracy for August and September 1944, the Allies stood a very good chance of destroying or damaging the Birkenau facilities while limiting the possibility of harm to those their efforts were designed to spare.”

Some historians have argued that bombing the gas chambers and crematoria at Auschwitz would not have mattered. The Nazis would have simply killed the prisoners anyway. However, this is mere conjecture. It took the Nazis eight months to build the crematoria and gas chambers in the first place at the height of Nazi power.

Erdheim writes that to rebuild the crematoria “would have been difficult, if not impossible” in the summer of 1944 with the demands of the war and a lack of skilled labor. Therefore, without crematoria, the Nazis would have had to revert to shooting the inmates and burning the dead bodies in the open air. However, Erdheim believes that “cremation ditches … were hardly a practical alternative due to the problems posed by the humidity as well as the threat of disease. It was for these very reasons, in fact, that Himmler had ordered the crematoria built in the first place.”

Transferring the prisoners to other camps such as Mauthausen and Buchenwald was not feasible as neither of these were extermination camps and they were not “capable of accepting a few hundred thousand inmates on short notice.”

Historian Richard Davis writes, “Given the six to eight weeks needed to accomplish the physical destruction of the gas chambers and crematoria … Auschwitz might have ceased to function by 1 September 1944…. Birkenau ceased its mass killing operations in mid-November 1944. For each and every day prior to this cessation, the complete destruction of its crematoria/gas chamber complexes might have saved more than a thousand lives…. The Allies could have bombed and destroyed Auschwitz. The Allies should have bombed and destroyed Auschwitz.”

If the Allies knew about Auschwitz and were capable of destroying it, then why didn’t it happen? It seems that when Auschwitz finally was within reach of U.S. air power by the late spring of 1944, the Allies were concentrating all their efforts elsewhere. As Tami Davis Biddle has written, “Military planners were consumed by a plethora of immediate war-fighting demands and problems…. The decision for nonaction [against Auschwitz] in the summer and fall of 1944 was made in the swirling vortex of competing wartime priorities…. Auschwitz was a distant and still poorly understood place that did not seem to have the same overriding claim on Allied resources as the Normandy invasion, the battle of France, the Nazis’ V-weapon launch sites, or the ongoing, costly ground battles in Italy.”

In a memo written in late June 1944 after the D-Day invasion, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander, listed the targets that the Allied air forces should bomb in order of importance. First were the V-1 and V-2 rocket launch sites and factories. The next priorities were “a. Aircraft industry; b. Oil; c. Ball bearings; d. Vehicular production.” Bombing Auschwitz was not even a consideration.

However, the argument that the American air forces were too busy and overtaxed to bomb Auschwitz is not a wholly convincing one. After the Soviet Red Army had driven to within 10 miles of Warsaw in August 1944, the Polish Home Army rose up in the city and tried to overthrow the Nazi oppressors. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill urged Roosevelt to help the Polish rebels. The next month, as the U.S. Army was struggling to take the port city of Brest, V-2 rockets were slamming into London, and Operation Market-Garden was failing in Holland, the U.S. Eighth Air Force received a new order to fly to Warsaw and drop badly needed supplies to the Home Army, including guns, food, and medicine.

Against the wishes of General Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, the commander-in-chief of the United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe, 107 B-17 Flying Fortress bombers escorted by 137 North American P-51 Mustang fighters left England on September 18, 1944, and flew over Warsaw. After dropping their supplies the planes landed in Poltava in the Ukraine. This mission shows that, contrary to what Assistant Secretary of War McCloy wrote, considerable air support could be diverted from decisive operations elsewhere and still not hinder the success of Allied forces.

Historian Donald L. Miller has asked, “Why were the Warsaw Poles supported, and not the Jews at Auschwitz?” The answer is that the Poles had more influence than the Jews did. As Miller writes, “At the time the Poles had what the Jews did not, a government in London, one with influence with Churchill.”

Historian Henry L. Feingold perhaps comes closest to the truth writing, “The destruction of the Jews of Europe was largely ignored … [because] the Jews of Europe were not fully part of the ‘universe of obligation’ that informs the Western world.” In other words, the Allies felt obligated to help Poles in Warsaw; there was no similar obligation to save Jewish women and children dying in gas chambers in Auschwitz.

The Allied governments knew about Auschwitz and what was happening there, Auschwitz was within striking distance of the U.S. Fifteenth Air Force in Italy, bombing Auschwitz would not have diverted substantial resources from the war effort, and the gas chambers more than likely could have been destroyed with minimal casualties. Erdheim concludes, “With the kind of political will and moral courage the Allies exhibited in other missions throughout the war, it is plain that the failure to bomb [Auschwitz] Birkenau, the site of mankind’s greatest abomination, was a missed opportunity of monumental proportions.”

Hugo Gryn was 13 years old when he was sent to Auschwitz. He lost both his mother and his younger brother in the gas chambers. After the war he said, “It was not that the Jews didn’t matter; [it was just that] they didn’t matter enough.”

Brent Douglas Dyck is a Canadian teacher and historian. His article, “Hitler’s Stolen Children,” appeared in the December 2013 issue of WWII History.

It’s also been stated that because the Nazis had committed so much of their rail rolling stock to transporting people to the camps that they were undermining their own war effort and disrupting that system might have freed more resources to be directed to the war effort. A very said calculus no matter how it is viewed and probably anti Semitism played a role no one really wants to admit.

Need

Good article need more like this one

A lot of “ifs” “could haves” and “maybes” in the reasoning of this article. It assumes a greater degree of accuracy of bombing than was normally achieved. Most importantly of all however, is the massive propaganda coup it would have given the Germans. Even if no prisoners had been killed by bombing, the Germans would obviously have had plenty of bodies to show, claiming them as victims. Goebbels would have had a field day. Neither is there any likelihood that killing would have stopped. More could have been starved to death, for example. The Holocaust is the greatest crime against humanity in history, but the only way to stop it was to win the war.

Fine article

I agree with David: I wonder would the killing have stopped? I don’t know that destroying the gas chambers and crematoria would have ended the killing. The Germans certainly wouldn’t have given them more food or clothing. They may have just been allowed to starve to death and then burned anyway. It’s difficult to project but maybe the prisoners would have been worse off, if that were possible.

Not to mention that even if all of this happened, the Jews still wouldn’t have been “free.” The Germans would’ve just used them to rebuild the camps. Airstrikes can be an effective way to deal blows to the enemy–just look at Desert Storm–but just like the Jews, the Kuwaitis wouldn’t have been free until the Iraqis were driven out of Kuwait

Goebbels would have a field day? Who cares. It would have saved many lives.

The Allies were blamed for a good number of things. Yet, nobody locally did anything to sabotage the railway lines to Auschwitz. Take into consideration that people went to extraordinary lenghts and even gave their lives to sabotaging trains carrying stolen art, yet did nothing to save Jewish lives. It is obvious, the average European considered art more precious than Jewish lives.

I understand your point Leslie; but it’s fair to remember that many Europeans did save the Jews at great peril to themselves and their families.

Could it be that bombing Auschwitz would be admitting knowledge of its existence? Something the allies denied for many years after the war ended.

Why do these articles about bombing targets in and around Auschwitz never include the possibility of independent action by the Soviet air force? To appease Stalin and encourage his partnership against Germany, the Western Allies were reluctant to apply any pressure on him. As a result, valuable western resources were diverted to actions in those parts of Eastern Europe that the Soviet Union could and should have had easy access to.

Yes, Franklin Roosevelt locked up Japanese-Americans, and refused to help the Jews.

The caption to the picture of the chemical is wrong. The picture is of the so-called Buna-Werke near the village of Monowice. The plant was built largely by slave laborers brought from Auschwitz II – Birkenau and from Auschwitz I. The Nazis then built Auschwitz III near the Buna-Werke. The plan by I.G. Farben was to produce synthetic fuel and rubber at the plant.

One relevant point to add to this discussion is that the Allied forces could have used low-level “light” bombers, instead of the ‘heavies”, to carry out a much more accurate precision bombing mission against the crematoria in Auschwitz. That was proved to be a very reasonable, feasible approach, as Operation Jericho, executed by low-level RAF Mosquitos attacking the Amiens Prison in France in Feb 1944, demonstrated.

In discussions and documentaries on this question, the evaluation of bombing always seems to be focused on high-altitude heavy bombers and American air forces. This is either ignorant or disingenuous.

Yes, the RAF Mosquito was the ideal aircraft for the job. Operation Jericho was the pinnacle of its potential. It had already proved itself very capable in 1942 of low-level precision bombing. It didn’t need fighter escort because it had enough speed to outrun German fighters. It also had considerable range to undertake long missions, such as the attack on the Oslo Gestapo headquarters. The Mosquito was also a very versatile aircraft with variants produced for numerous roles. One extremely lethal variant was the FB Mk. XVIII Tsetse, armed with a Molins 6-pounder cannon, capable of destroying ships and U-boats.

WHAT ABOUT MADAGASCAR!!!!!!

Typical “what if” stories. Seems strategy would have been the right thing to do but with the knowledge and technology at the time it seemed better to bomb the support industry. Come over to America and drop your stuff on the Lockheed factory would be more strategic than taking out Manzanar.

The author seems to demonstrate some bias.

1. “The U.S government believed that the best way to save the Jewish people being murdered at Auschwitz was to defeat the German Army and force Hitler to surrender.”

2. “After the Soviet Red Army had driven to within 10 miles of Warsaw in August 1944, the Polish Home Army rose up in the city and tried to overthrow the Nazi oppressors.”

Helping the Polish Home Army to fight the German army is directly in line with the stated goal of destroying the German army. The author completely failed to mention this as a possibility.

The last sentence of this article says it all. Little wonder the Jews decided to redouble their efforts after the war to re-establish a homeland in Palestine.