By William G. Dennis

Today, on Hill 192, located between the Normandy cities of St. Lô and Bayeux, sleek horses graze the fields, and people in hacking gear travel the roads and bridle paths. The “farm” houses and outbuildings have the polished look of some wealthy Parisian’s country retreat rather than the more rugged appearance of a working farm. It is a peaceful, relaxed, almost bucolic place.

However, for a few weeks in June and July 1944, it was very different place indeed. The fighting there was a microcosm of what was happening to American Army units experiencing their baptism of fire. As the fight for Hill 192 unfolded, it became clear that the American units involved in the battle were improving rapidly. They were going to give Germany some serious—and ultimately insoluble—problems.

Still, on June 16, 1944, Lieutenant Raymond Lee was a worried man. As the communications officer of the 23rd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, he was in a good position to follow the course of his division’s battle. The 23rd, along with the 9th and the 38th, were the infantry regiments of Maj. Gen. Walter M. Robertson’s 2nd Infantry Division that had begun landing on Omaha Beach on June 7. They initially moved southwest against scattered opposition.

American infantry divisions in World War II contained the components they would likely need in virtually all circumstances. Their table of organization and equipment (TO&E) included three regiments of infantry, each containing three battalions of about 850 men, plus heavy infantry weapons held at regimental headquarters; four battalions of artillery with a dozen guns apiece; and supporting units such as engineers, medical services, military police, and supply services. A large pool of separate battalions of tanks, anti-aircraft guns, tank destroyers, engineers, and the like was available to augment the infantry divisions as needed.

In contrast, by this point in the war a German army division was a much smaller organization. By the Normandy campaign, a German rifle company’s TO&E was only about 80 men, and it was often well under this strength. The German Army attempted to compensate for this lack of manpower with a lavish issuance of automatic weapons.

There were only six infantry battalions and a seventh “fusilier” battalion, which was supposed to employ the German division’s heavy infantry weapons but sometimes was used as a maneuver battalion. The artillery component was similarly reduced. Much of their artillery and other heavy equipment was material

captured from the armies they had defeated in previous years.

The Germans deployed two other armies—the Waffen-SS, which was the combat arm of the Nazi Party, and the Luftwaffe, which had its own land army of about 25 divisions. There were several paratroop divisions, a Luftwaffe panzer division, and the rest were infantry divisions. The Luftwaffe divisions were larger than Heer (Army) formations and more lavishly equipped but generally lacked well-trained leadership.

On the whole, Robertson’s 2nd Infantry Division was well trained but, like many infantry divisions, it had had little opportunity to train with tanks. So tank-infantry cooperation was not one of the division’s strong points. This problem was so widespread that later in the war it became standard practice to attach a tank battalion to a given infantry division on a semi-permanent basis so that the units could become comfortable working with each other.

Developing procedures to work with tanks was something the division would have to do after entering combat. One of the first things done was to develop hand signals that both parties understood.

The infantry support for “general headquarters” tank battalions also needed to hone their skills. They were formed by the new Armor branch and given the same training as the battalions assigned to armored divisions. In many cases they were formerly part of an armored division and had been detached when the U.S. Army adopted a smaller, more manageable TO&E for those divisions—one that had fewer maneuver battalions.

The armored divisions were trained to make deep penetration attacks into the enemy’s rear. For tanks that would normally be attached to the infantry divisions, this was not the right training; they required procedures that would enable them to cooperate effectively with infantry.

The 741st Tank Battalion (Separate) was attached to the 2nd for the Hill 192 attack, they had not trained together. Additional support was provided by two battalions of tank destroyers (TDs)—tracked and turreted vehicles that had a superficial resemblance to tanks. Unlike tanks, they were lightly armored and the turrets were open on top. Possessed of high-velocity main guns, they were intended to speed to the site of a German breakthrough and engage the German spearheads.

With Germany on the defensive, other uses were being found for the TDs. Because of the light armor and open turret, it was necessary for them to stay slightly behind the front lines, but, when called upon, their high-velocity guns could readily penetrate buildings and bunkers.

Many units were experimenting with ways to move tanks and other tracked vehicles through the French hedgerows. Most of them involved explosives, but it took a huge amount of explosives to breach the dozens of hedgerows in the path of any one attacking unit. The explosions also alerted the Germans that an attack was coming.

Units were also developing methods that did not necessarily involve explosives. There were a limited number of tanks available that were equipped with bulldozer blades. They worked well but were far too few for the attack. The few that were available were attached to the 2nd Infantry Division. Some units had improvised heavy bumpers and mounted them on tanks to push through the hedgerows.

During the first few days it had not been difficult for the 2nd Infantry “Warrior” or “Indianhead” Division (so named because of the fully head-dressed Indian warrior on the division’s sleeve patch) to advance because much of their opposition came from reluctant non-Germans who had volunteered or been conscripted into the German Army.

The Poles, Russians, and central Asians that the Warriors encountered were not enthusiastic about fighting for Germany against Americans in France. The Germans employed large numbers of such troops in their coastal defense “static” divisions. A German sergeant assigned to one of these units needed eyes in the back of his head. Given an opportunity to surrender to the Western Allies, these men were in the habit of shooting their NCOs and waving white flags.

With soldiers like this in their army, there was a wide variation in the quality of German units. But Robertson’s division was about to discover that Germany still had some well-trained, well-equipped, and highly motivated units in front of them.

The Germans would stand and fight hard but often found themselves fighting for real estate that was impossible to hold. Nevertheless, their commanders ordered them to stand their ground because the Germans could not afford to let the Allies out of the Cotenin Peninsula. The armies the Allies brought to Normandy were far more mobile than the Germans, and the American army was the most mobile army in modern history.

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, who commanded the German armies facing the Allies in Normandy, once believed that the American M4 Sherman tank was superior to any tank available to him when he commanded the Afrika Korps, but it had become outdated by this stage of the war. Still, it was far more mechanically reliable than anything the Germans had.

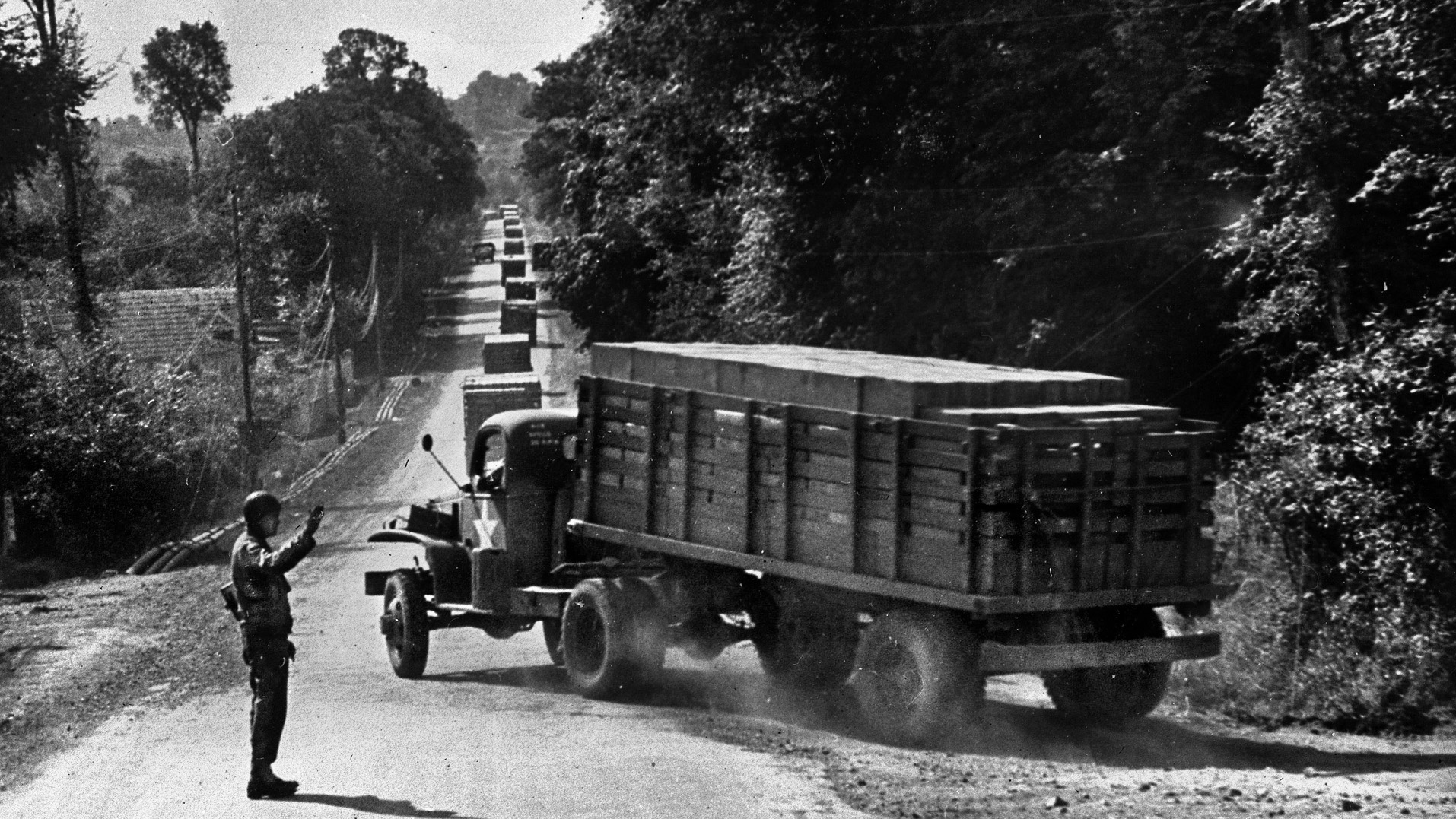

Also, the American 2.5-ton truck could go places where most of the vehicles available to the Wehrmacht would likely stick fast, if they had not already broken down. (Field Marshal Erich von Manstein once remarked on how much more mobile Russian artillery had become once the Red Army received American Lend-Lease trucks.)

Much the same was true of other U.S. equipment, like the half-track troop and weapons carrier. The infantry assigned to American armored divisions—the armored infantry battalions—were fully equipped with such vehicles. Most of the troops in the elite panzer divisions were lucky to be carried into battle in unarmored trucks.

The German infantry was even more poorly equipped, with most of its heavy weapons and equipment moving by rail and/or horse-drawn wagons.

Set loose on the plains and rolling hills of northern France, the Allies would easily outmaneuver the plodding Germans. The Germans made some efforts to prepare the line of the Seine River for defense, but their best hope was to keep the Allies penned in the Cotenin Peninsula until the winter storms interrupted the flow of supplies across the beaches and starved the Allied armies and grounded Allied aircraft.

Perhaps by then Hitler’s long-awaited “secret weapons”—rockets and jet planes—could play a decisive role. So the Germans’ hitherto light resistance stiffened as the 2nd Infantry Division approached Hill 192—20 miles south of Omaha Beach and four miles east of St. Lô, between the villages of la Calvaire and la Croix-Rouge, in June 1944.

Hill 192 gave the Germans good observation for miles in every direction. It needed to be taken quickly in order for Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, the American 12th Army Group commander, to drive behind the German left flank and break out of Normandy—the attack that would become Operation Cobra.

Hill 192’s slopes are too gentle to be much of an obstacle, but the north side is ideal for defense. It is classic bocage country—a terrain of tiny, irregularly shaped fields and apple orchards surrounded by hedgerows—walls of mounded earth several feet high with a lush growth of brush and trees on the sides and top. The terrain provides defenders cover, concealment, and excellent fields of fire, while troops attacking through the fields are fully exposed to the defenders. The south side of Hill 192 was covered with heavy woods, and orchards dotted the slopes.

Between many of the hedgerows are sunken lanes lined by more trees whose branches interlock and hide the lanes from the air. Lt. Gen. Joseph Lawton “Lightning Joe” Collins, commanding the U.S. VII Corps, found it worse country to fight in than Guadalcanal; at least in the Pacific the attacker, too, had some cover. (Several times this author walked across a field toward a hedgerow trying to imagine what it was like for attacking GIs. It was not a comfortable experience.)

The Germans were about to learn that the hedgerows were not quite as formidable defensive positions as they appeared to be. The peasants who built them saved all the rocks they found and fortified the mounds with them. They would stop a rifle bullet, but .50-caliber rounds and larger could pass right through.

The hedgerows and Hill 192 were defended by troops of the nearly 16,000-man 3rd German Fallschirmjäger (Parachute) Division, commanded by Generalleutnant Richard Schimf. According to at least one historian, the hill was one of the most heavily defended areas in the American portion of the front.

The 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division was an elite unit that included significant numbers of fanatical Nazis. The division was formed near Reims, France, in October 1943, and since February 1944, it had been stationed near Brest in anticipation of an Allied invasion. Having trained in Brittany, the troops were familiar with bocage country.

Besides having terrain that was some of the most favorable to the Germans’ defense of Europe, the troops were some of the most heavily armed light infantry in the world. Each company was equipped with 20 of the formidable MG 42 machine guns and 43 submachine guns. Each squad had two of the MG 42s and five machine pistols. If they were short on artillery, they were heavy on mortars, whose positions are harder to spot from the air. All of their tubes were preregistered, so fire could quickly be directed where it was needed.

The American rifle squad was armed with one BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) and a single Thompson submachine gun, while the rest of the men carried M-1 Garand rifles.

Although the 2nd Infantry Division was formed in 1917 and fought in World War I, Normandy would be its introduction to combat in World War II. Luckily, many of its regimental and battalion commanders were “old hands” at the business of training young men for war.

The division had moved to Northern Ireland in late 1943 and to England in April 1944 before sufficient M-1s were available to arm all its riflemen. The 23rd Infantry Regiment men were carrying old-fashioned, bolt-action Springfield .03s—leftovers from World War I.

According to Bill Dudas, who served in the 38th Infantry Regiment, his unit, too, initially carried Springfields. The disadvantages of a bolt-action rifle in the close combat of the hedgerows quickly became clear, he said, so, “We threw our Springfields in a heap and were given M-1s.”

To keep Bradley’s advancing forces from being struck in the flank, his units needed to reach and hold the transportation hub of St. Lô. This would prevent a German move from Bérigny to the east and put the Vire River on the flank of the planned advance. If the Americans could capture the city and have a river to protect their flank, the Germans’ ability to counterattack would be severely limited.

There was not much left of St. Lô worth holding. It had been reduced to rubble by Allied warplanes on June 6 and 7, leaving some 800 inhabitants dead. As the Army’s official history says, “Allied planes … made concentrated and repeated attacks that seemed to the inhabitants to have been motivated by the sole intention of destroying the city.” The crossroads that it controlled, however, was still important, so it remained a vital objective.

On June 10, the 2nd Division, moving south from Omaha Beach, had attacked across the Aure River and liberated Trévières. For the next several days, little German opposition was encountered, the disorganized enemy having retreated farther south to more defensible ground.

The opportunity for Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ U.S. First Army to seize St. Lô now presented itself. Four American infantry divisions—the 2nd, 29th, 30th, and 35th, a combination of XIX and V Corps units—had moved southward from the Normandy coast and were arrayed north and east of the city.

To mount a successful attack on St. Lô, the Americans needed to have their eastern flank protected by Hill 192. Opposing them were elements of the LXXXIV Corps and II Fallschirmjäger Corps.

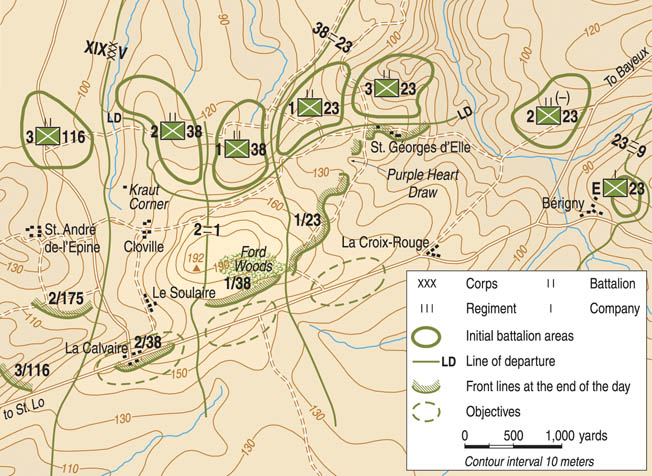

Hill 192 was important because it was the highest point in this sector, offering whoever held it long-range observation for miles around. V Corps commander Leonard T. Gerow assigned the task of taking the hill to the 2nd Division, then in its assembly area north of Cerisy-la-Forêt. According to the plan, the 23rd Infantry Regiment, under Colonel Hurley E. Fuller, would assault and secure Hill 192 while the 9th Regiment would take the high ground south of Littcou; the 38th Regiment would be in reserve.

The order called for the 23rd Regiment to pass through the position held by the 38th Regiment with the 1st and 2nd Battalions; the 3rd would be in reserve. The 1st Battalion would cross the Elle River west of Cerisy-la-Forêt and move south against Hill 192 while the 2nd Battalion would attack southwest and take the east slope of the hill. The 2nd Battalion would move south to the highway that ran from Bayeux to St. Lô through the village of Bérigny.

The German parachutists had organized several strongpoints and placed a counter-reconnaissance screen ahead of their main line of resistance. All their positions were well dug in and extremely well camouflaged on the heavily forested hill. Machine-gun nests were numerous, and German gunners located on the rear slope had preregistered their artillery on every likely avenue of approach.

The 29th and 35th Infantry Divisions would begin their attack southward toward St. Lô on June 11. The jump-off did not go well, and the scheduled start was disrupted. Eventually the 29th found its footing and pushed into German positions on the Martinville ridge.

Truth be told, the 2nd Division was not ready for the attack on Hill 192—its first combat action of the war. According to a Captain Calder, at the time a battalion adjutant in the 23rd, the officers leading the attack had not personally reconnoitered the ground and their briefing was conducted well to the rear where they could not see the objective they were about to attack.

Additionally, the troops were still getting used to the strange terrain and were extremely uncomfortable crossing the open fields walled in by hedgerows. Moreover, many of the division’s mortars and machine guns had not yet been brought up. Nonetheless, the attack began with an artillery barrage at 5:40 am on June 12.

Selected to lead the attack was Company F, 2nd Battalion, 23rd Regiment. It did not get far; the advancing troops were cut down by rifle, mortar, and machine-gun fire. Lt. Col. Raymond B. Marlin, 2nd Battalion’s commander, ordered Company G to move around Company F’s left flank and continue the attack, but the intensity of German fire increased.

To support the infantry, American artillery hit enemy positions while Companies F and G attempted to advance. These moves went nowhere as the companies took casualties and went to ground. Once pinned in place, the Warriors were savaged by mortars and artillery.

With Companies F and G halted, Company E of the 2nd Battalion, 23rd Regiment moved out from the Cerisy Forest toward Bérigny on the St. Lô road. Very quickly they began receiving fire from snipers hidden in the trees and hedgerows, but then the situation grew quiet. The company reached the eastern edge of Bérigny where the men took cover in the abandoned buildings.

While this action was taking place, Colonel Fuller ordered Lt. Col. William S. Humphries’ 1st Battalion to move up to the west of the 3rd Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Paul V. Tuttle, Jr. Humphries’ men had not gone far after crossing the line of departure when the Germans counterattacked and pushed the battalion back about a mile. The two opposing lines were so close that, in some cases, the Yanks fired grenades at their opponents using inner tubes from tires as slingshots.

With all three battalions of the 23rd Infantry Regiment now more or less pinned down by small arms, machine-gun, and mortar fire, the attack on Hill 192 petered out, and in the early afternoon Fuller ordered his men to organize a defense in anticipation of a counterattack. Positions were dug and crew-served weapons were sited and emplaced.

American fire support was ineffective because forward observers for the mortars and artillery could not locate targets in the forested terrain. Supporting tanks, stuck in tree-lined lanes, became targets for panzerfausts (shoulder-fired antitank weapons) or were knocked out by mines. Those that tried to roll up and over the hedgerows exposed their thinly armored bellies to German gunners.

East of the hill elements of the 23rd Regiment, aided by tanks, were able to knock out several German strongpoints to grab a commanding view of the Bérigny highway—the eastward exit from St. Lô.

Aid stations were established close to the front; the 2nd Battalion alone had suffered 211 men killed or wounded on June 12. As daylight was fading, American aircraft cruised over the scene and dropped their ordnance on Hill 192.

That evening the Germans engaged in the usual counterattacks they employed whenever they lost a piece of ground. The German commander remarked that, had the Americans continued their attacks, they likely would have broken through their lines and would have had a clear shot toward St. Lô.

The Germans began their major counterattack shortly after 1 am on June 13, primarily hitting Marlin’s 2nd Battalion, 23rd Regiment with rifles, machine guns, mortar, and self-propelled artillery fire. The Americans fired back blindly into the darkness toward muzzle flashes. Mortars and artillery, too, were fired at supposed enemy locations, but no one could be sure. The firefight lasted about an hour and then suddenly ceased.

Marlin was concerned that the Germans’ nocturnal activities had been a “reconnaissance in force” and probably a prelude to an even more concerted push come daylight against his 2nd Battalion—an attack that, oddly, didn’t come. Nevertheless, the men used the lull to improve their defensive positions and prepare for whatever the Germans might throw at them.

Meanwhile, 2nd Division G-2 (Intelligence) learned from POWs that elements of the 8th Fallschirmjäger Regiment of the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division were in the Bérigny area and the German 352nd Infantry Division was north of Hill 192 around the village of St. George d’Elle.

While the 2nd Division’s 2nd Battalion, 23rd, seemed to have been spared further combat on June 13, the same cannot be said of the 9th Infantry Regiment. Colonel Chester J. Hirshfelder’s regiment suddenly found its positions being probed by patrol elements of the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division.

Throughout the day, harassing German mortar fire continued to fall in the 2nd Division area. A night attack was expected, but none materialized. For the next two days the situation was relatively quiet. Rather than wait to be hit by the Germans, Robertson and his staff began planning for offensive action on June 16 to regain the initiative.

Replacements began arriving and were assigned to the hardest hit companies. When the Germans noticed the activity, they stepped up their mortar fire but without causing casualties.

The plan of attack for June 16 called for a 15-minute artillery preparation on Hill 192 followed by all three regiments attacking abreast, with the 38th on the right flank, and the 9th Regiment poised to seize St. Germain d’Elle. The 23rd Regiment would then attack Hill 192 with the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, with the 1st Battalion in reserve.

The 3rd Battalion’s objective was the hamlet of St. George d’Elle and then the east slope of Hill 192; the 2nd Battalion, advancing on Hill 192 proper, would link up with the 3rd Battalion and move against la Vallee Queron. Company E of the 2nd Battalion, scheduled to hit Bérigny, would have a platoon of Sherman tanks attached.

At dawn on June 16, American artillery opened up and Hill 192 disappeared under clouds of dirt and flying trees. East of Bérigny, Company E and the tanks crossed their line of departure, but the leading tank was knocked out by a shot from a panzerfaust, blocking the road about 300 yards east of the village.

Undeterred, the rest of the tanks fanned out into the fields on both sides of the road, the infantrymen following in their wake. But the attack stalled when it was discovered that the hedgerows were too great an obstacle for the tanks.

Company G’s attack was faring better. Despite intense enemy small-arms fire and mortar rounds saturating the area, Company G managed to cross the Elle River and advance from one hedgerow to another until 3rd Battalion was 400 yards beyond St. George d’Elle.

Even without tank support, Company E continued advancing toward Bérigny—in spite of being hit with practically everything in the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division arsenal. Once the Americans penetrated into the village, the battle became a house-to-house fight. Slowly the Yanks managed to push the paratroopers out but were then subjected to a vicious counterattack that was only stopped by the timely arrival of American artillery. The Germans were blocking Company E’s attempts to move forward out of the village.

In the Company F, 2nd Battalion, 23rd Regiment sector, an attempt to make contact with Company G was halted by concentrated German fire while it tried crossing a stream. No sooner had the artillery and mortar fire lifted than German troops counterattacked and forced Company G back across the stream—all the way back to its line of departure. To maintain the battalion front, Company F was ordered back to its previous position.

By early afternoon it became obvious that the 2nd Battalion could not advance any farther. Lt. Col. Marlin’s men ceased all attempts to move forward and began preparing their positions for defense.

While the 2nd Battalion, 23rd Regiment assault was stymied, Colonel Walter A. Elliott’s 38th Infantry Regiment, to the right of the 23rd, was having better success. Attacking the north slope of Hill 192, Lt. Col. Malcolm R. Stotts’ 3rd Battalion, 38th Regiment was able to fight its way up to the crest of Hill 192, but later had to abandon it.

On the 16th, one rifle company managed to reach the crest of Hill 192, but a counterattack drove it back down the hill. To steady the American line, the division’s 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion was rushed in to assume the role of infantry.

At St. German d’Elle, however, Hirshfelder’s 9th Infantry Regiment had only advanced 300 yards from its line of departure before it ran into determined resistance and was stopped cold. This ended the 2nd Infantry Division’s initial attack on Hill 192.

After four days of fighting and little progress, the attack was called off. Depending on the source one reads, the attack cost between 1,200 and 1,250 American casualties. The most important reason the attack failed was that the Americans had not yet adjusted their tactics to the conditions in the bocage.

Through the remainder of June, the 2nd Division maintained its positions, occasionally being shelled by German artillery and mortars and strafed by German aircraft. On June 19, Lt. Col. Humphries, commanding the 1st Battalion, 23rd Regiment, was wounded in action and was replaced by Lt. Col. John M. Hightower.

Further attempts to take Hill 192 and St. Lô were put on hold until July 10, 1944, but the 2nd Division continued to refine plans for renewing the offensive on the feature.

During this period of limited combat, the division reviewed the lessons learned and determined how to improve its performance in the battles yet to come. Better reconnaissance of the battlefield was vital, as was closer coordination with armor, artillery, and air support. More vigorous patrolling was deemed necessary, as was improved security to ward off enemy probes. Better interrogation of prisoners was also considered vital to gain intelligence about the foe.

The low number of automatic weapons was also discussed, and the division was allocated a greater number of automatic and semi-automatic weapons to counter German superiority in firepower.

Armor and artillery liaison officers were also brought into the planning for the next attack on Hill 192. The artillerymen exploited the flexibility that good radios, modern fire-direction centers that could control the fire of multiple batteries, and spotters well forward on the ground and in the air gave them. Special maps showing all the fields, hedgerows, buildings, sunken roads, and trails were distributed so that mortar and artillery fire adjustment could be made quickly and precisely.

According to Maj. Gen. Robertson, the targeting to support the attack “was later described as one of the best planned of the war in Europe.” The emphasis in training for the attack was on the infantry, armor, artillery, and engineers all working as a team. Robertson said the plan was to move “as a unit, the engineers blasted the earthen walls with demolitions, the tanks plowed through, the infantry surged through the gaps supported by tank fire, to seize these otherwise unyielding positions.”

To plow through the hedgerows, tanks, like the ones supporting the 2nd Infantry Division, were outfitted as “Rhinos” with hedgerow cutters—pointed metal horns welded onto the front of the hull to dig into and break through the hedgerow instead of rising over it. (These cutters were the brainchild of Sergeant Curtis Cullen of the 102nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron.) The Germans had strewn the beaches of Normandy with obstacles; there is a delicious irony that these obstacles supplied most of the metal for the horns.

Several authors have written that the Rhino was such a potential “game changer” that Lt. Gen. Bradley ordered them to not be used until Operation Cobra. But Maj. Gen. Robertson’s book, Combat History the Second Infantry Division in World War Two, discusses their use at Hill 192.

Lieutenant Colonel Frank T. Mildren, who commanded the 1st Battalion of the 38th during its successful attack on Hill 192, wrote a monograph after the war that also indicated that Rhino tanks were used in the second attack.

Even the light Stuart tank, fitted out as a Rhino, could be an effective hedgerow buster. But when the Rhinos were first deployed, no one was sure if the horns would always work. So racks to carry the engineers’ breaching charges were installed on the back decks of the Shermans supporting the Warriors.

Each company formed several attack teams based on an infantry squad with an attached Sherman and a few engineers trained to breach the hedgerows with explosives. The squad’s armament was augmented with an extra BAR or Thompson and in some cases with a .30-caliber machine-gun team—the gun on a special spike mount to facilitate rapid emplacement on top of a hedgerow.

On June 20, a new American attack plan was being considered. This time there was good reconnaissance along the front lines and from liaison aircraft, although patrols sent forward of the lines were regularly “badly shot up.”

According to Cleve Barkley, the son of a 2nd Infantry Division veteran, the one exception was the Winstead patrol. On the night of July 6, 1st Lt. Ralph Winstead and his men of the 38th Infantry Regiment crept forward toward an area dubbed “Kraut Corner,” which bristled with machine guns and mortars. The patrol moved under the cover of American artillery and mortars firing on German positions until the troops were within yards of the German dugouts and trenches.

Satchel charges and Bangalore torpedoes (explosives packed into long, connected poles) stunned the defenders long enough for Winstead’s troops to break into a strongpoint and begin a point-blank firefight with the shocked Germans. They inflicted an estimated 11 casualties against three of their own and returned with valuable information about the location of German machine-gun and mortar positions.

Around this time, Tech. Sgt. Frank Kviatek, an expert marksman and World War I veteran, became a hero in the 2nd Division. Full of anger over the loss of his two brothers killed in Italy, he vowed to kill 25 Germans for each of his brothers. He used a bolt-action Springfield rifle with telescopic sight to pick off 21 Germans, mostly snipers. He was later wounded but returned to combat to account for another 15 of the enemy. He became the first 2nd Division soldier to be awarded the Silver Star.

Finally, on July 10, the American drive to take St. Lô was resumed with the capture of Hill 192 a key element. While the 29th Infantry Division made a major push southwest toward St. Lô, Robinson’s 2nd Division crossed its line of departure for another go at Hill 192.

This time the 62nd Armored Field Artillery Battalion was attached to the 2nd Division with two battalions of the 1st Division and the guns of the corps artillery and one combat command of the 2nd Armored Division to support the attack.

The Army’s official history notes that Colonel Ralph W. Zwicker’s 38th Infantry Regiment (he had replaced Elliott on July 5) “was assigned the mission of taking Hill 192 proper, attacking with two battalions abreast on the right of the division front. The 23rd Infantry (Colonel Jay B. Lovless), fighting in the center of the division zone, was ordered to attack with two battalions in column in the general sector of St.-Georges-d’Elle-la Croix-Rouge, making its main effort in the west of its zone, on the eastern slope of Hill 192, in order to cross that slope and secure the St.-Lô-Bayeux highway from south of the hill east through la Croix-Rouge. The 9th Infantry, on the eastern flank of the division front, was directed to support the attack by all available fires.”

An hour before the ground attack commenced, artillery shells—more than 25,000 rounds in 60 minutes—rained down on the 3rd Fallschirmjäger’s positions––the heaviest artillery concentration up to that point in the battle for Normandy. As American troops came upon survivors, many Germans surrendered, too stunned by the intensity of the shellfire to resist.

Sherman tanks, too, were in abundance, with three tanks assigned to each infantry platoon. The tanks had special EE-8 phones installed on the rear and connected to the tanks’ interphone system for tank-infantry communication during action. A soldier walking beside or behind the tank could spot targets, such as an aperture of a bunker or a rifleman in a window, and point them out to the tank commander. A writer cited these experiments as examples of an “entrepreneurial spirit” that encouraged a free flow of ideas within the American Army.

Aircraft were also scheduled to take part but low visibility caused by clouds and fog called off all but one sortie. After units of the 38th Regiment were accidentally struck in a friendly fire incident, further airstrikes were cancelled until visibility improved.

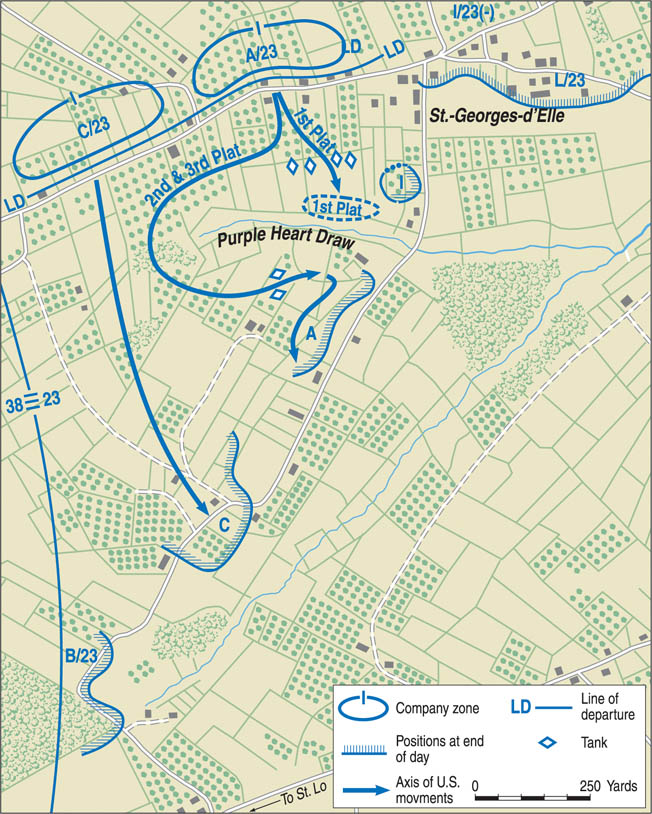

Hightower’s 1st Battalion of the 23rd, with Company A on the left and Company C on the right, jumped off at 6 am from the line of departure on the Cloville-St.-Georges-d’Elle road (attacking from the road that ran west out of St.-Georges-d’Elle). Company A’s initial advance was without incident until it reached a defile that became known as Purple Heart Draw, where the Yanks were caught in a murderous fire that inflicted heavy casualties.

Company C had it easier, moving forward without serious opposition. Effectively using rifle grenades, the company knocked out several enemy machine-gun emplacements. Company L of the 23rd’s 3rd Battalion, however, had run into a hornet’s nest and taken many casualties while trying to gain a hedgerow to the east of St.-Georges-d’Elle. But Company L’s efforts helped keep German forces in that sector from shifting troops to the main zone of attack.

At 6:30 am, the 38th Infantry Regiment began moving toward Hill 192, with Mildren’s 1st Battalion on the left and Lt. Col. Jack K. Norris’s 2nd Battalion on the right, both following closely behind a rolling barrage. Two companies of the 741st Tank Battalion, a company of the 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, and a company of the 81st Chemical Mortar Battalion supported the attack.

By the end of the day, Hightower’s 1st Battalion had gained 1,500 yards and dug in for the night 400 yards from its objective, the St. Lô-Bayeux highway.

To the east of Hill 192, the Germans still had a tenuous hold on Purple Heart Draw, but it had become a salient that could not be held long term. Despite the fact that the Germans had plenty of panzerfausts and antitank grenades, close support by the infantry prevented any tank casualties.

After taking Cloville, Norris’s 2nd Battalion bypassed the village of le Soulaire and reached the west slope of Hill 192 and then, at about 5 pm, its forward elements crossed the St. Lô -Bayeux highway while under fire.

Throughout July 11, combat engineers had been blasting holes in the hedgerows through which tanks could charge while hitting the next hedgerow with their main guns and machine guns. With the Germans pinned down, American infantry, following behind the tanks, was able to charge enemy positions successfully.

Whatever its deficiencies as a tank-killing gun, the medium-velocity 75mm gun on the Sherman was an excellent infantry support piece. The velocity was still sufficiently high that it readily penetrated hedgerows and bunkers.

The Sherman’s bow gunner and tank commander would fire their machine guns, traversing along the hedgerow in front of them. The .50-caliber rounds of the commander’s gun would usually punch right through any hedgerow, especially where it had been hollowed out to form a machine-gun bunker. The exit wound from a hit to the body could be as large as the diameter of a football, and any round that hit an arm or leg usually removed it.

Pairs of riflemen scouts would fan out around the margins of the field tossing grenades over the hedgerow. If the Germans somehow avoided becoming casualties and pulled back, making a stand brought quick and accurate artillery with ground troops moving up behind it.

An assault on one of the strongpoints went surprisingly well because by that time the Germans had been so weakened that their commander had ordered a withdrawal. By late in the day the Americans had reached the woods on the south slope of Hill 192 and could advance more easily, partly because of slackening German resistance and partly because the woods gave better cover than the open fields to the north. By day’s end, the attackers controlled most of the hill and were across the road at its base.

Lieutenant Colonel Mildren pointed out that the defenders were so shattered that they failed to mount the usual counterattack that almost always followed a German retreat.

American accounts of the battle emphasize the Germans’ desperate resistance in the opening phases of the battle. “Heavy mortar and machine-gun fire” and similar phrases are sprinkled liberally throughout them. The fanaticism of the German defenders made them so determined that some of them refused to surrender and had to be buried alive in their bunkers.

American accounts also complain frequently about German “snipers,” who were mostly infantrymen armed with ordinary bolt-action Mausers and with no special training.

Some American companies sustained heavy casualties, yet overall the casualties were comparatively light. Most assault companies had to commit their reserve platoon and at least one battalion committed its reserve company. But it is noteworthy that neither the 9th nor the 23rd Regiment had to commit its reserve battalion.

Aiding in this effort, armored bulldozers or tanks with scoops mounted on their bows filled in sunken roads or plowed over machine-gun nests, burying their crews.

One dozer operator, Private John R. Brewer, 741st Tank Battalion, saw three Germans behind a hedgerow firing at the advancing troops with their machine pistols. He smashed the hedge over the trio, burying them alive.

Second Lieutenant Mac L. Basham, 38th Infantry Regiment, routed one enemy soldier from his hole and then made the German accompany him to other positions to order out his comrades. After taking seven prisoners this way, Basham turned them in, secured the aid of two enlisted men, and together they drove five more from dugouts.

By late afternoon on July 11, “The Hill” belonged to the men of the 2nd, but the battle was not yet over. That evening the Germans lashed out with artillery fire and small counterattacks, but it was clear the Germans were on the losing end. The next day, the 2nd Division resumed the assault at 11 am with a drive spearheaded by Mildren’s 1st Battalion of the 38th. Resistance quickly crumbled as the Germans pulled out.

By the end of July 12, the 2nd Division held not only Hill 192 but also the St.-Lô highway as far west as la Calvaire. Their victory had cost the 2nd Division 69 killed, 328 wounded, and eight missing. The left flank of the main drive on St.-Lô had been cleared of a formidable obstacle, and the Americans had gained the best ground for observation on the battlefield.

The training for the attack that included the infantry, armor, artillery, air, and engineers had paid off.

With the 2nd Division now in possession of Hill 192, the rest of V and XIX Corps could concentrate on taking St. Lô. On the right flank of the 2nd Division, the 29th Infantry Division moved simultaneously against the high ground closer to St. Lô to position itself for its attack on that city.

There were enough German positions that survived the barrage and remained capable of putting heavy machine-gun fire on any troops maneuvering in the open against them, plus enough German mortars and artillery to make the place hot. Additionally, a number of the tanks fell victim to panzerfausts, mines, and artillery.

Not everything went well for the attackers. Carrying breaching charges in the open on the back decks of Shermans when hot steel from tree bursts was flying around was not someone’s best idea. In several instances the explosives stored on the Shermans blew up, destroying the vehicles. But even the attack teams without tank support drove in the outpost line and put heavy pressure on the strongpoints.

The rest of the tanks supporting Company A, 2nd Battalion of the 38th, pulled back; it took several hours to remove the cases of explosives from them and get them back into action. Company A sustained so many casualties that it became ineffective; Company C’s attack in the battalion’s righthand sector was more successful.

It had been overcast and foggy when the attack started, initially keeping spotter planes on the ground. After several hours, the fog briefly lifted, which allowed air strikes to begin and the spotter planes to go into operation. Later that afternoon, the clouds closed in again, and the remainder of the strikes had to be canceled. Even so, by midafternoon Mildred’s battalion was atop the hill and moving down the reverse slope.

When the American attack rolled forward, it looked like this: artillery would fall heavily on German positions. As it lifted, the hedgerow in front of them would erupt with automatic weapons fire and be violently breached, perhaps by an explosion but increasingly, as they proved their worth, by the horns of a Rhino tank. The tank would roll through the gap, firing its main gun at suspected machine-gun positions in the corners of the fields, followed by infantrymen charging through and firing at everything.

The 2nd Infantry Division’s attack and capture of Hill 192 was an outstanding success, directly preparing the way for the 29th Infantry Division’s bloody battle for St Lô.

Meanwhile, other troops were clearing the Allied rear by capturing Cherbourg and battling their way south through the hedgerows and swamps in the center of the Cotentin Peninsula. The interim objective for those troops was to draw up to the Piers-St Lô road with a firm grip on the latter. This gave General Bradley an excellent place from which to launch Operation Cobra on July 25, 1944.

The 2nd Division had taken heavy casualties. There were only about 2,700 men in the rifle squads of a full-strength American infantry division; the division lost about 1,600-1,700 men in the two attacks, and a great many of them were from those squads.

But the Warrior Division was not so badly hurt as to cause the organization of any of its subordinate units to collapse or for an influx of replacements to change the character of the division. It remained a proud, cohesive force.

The ranks were replenished with replacements and men returning from hospitals. The division was thrown again into heavy combat, this time in the assault on Brest. The division was replenished once more and, in the fall of 1944, sent to the Ardennes Forest on Germany’s western border with Belgium. There it rested in a quiet sector until called upon to pass through the 99th Infantry Division and assault the West Wall. Just as that assault was achieving success, the Battle of the Bulge began. The 2nd and 99th Infantry Divisions were in the path of the planned German advance and stopped it cold.

The failure of the first attack on Hill 192 made a great impression on Lieutenant Raymond Lee. That is clear from the paper that he, by then a major, wrote during his advanced infantry officer’s course at Fort Benning, Georgia. He realized that the real story of the fight for Hill 192 was not the failure of the first attacks in June but how quickly and rapidly the units involved rose above that failure.

He recognized that the creation of the tank-infantry-engineer assault team was a major part of the solution to the problems of hedgerow warfare. It furnished a clearcut example of the importance of the ingenuity and resourcefulness of American troops under varying combat conditions.

Indeed, the attack was one of the best examples during the Normandy campaign of combined arms attacks that made good progress with few casualties.

The 2nd Division was only one of many units demonstrating that adaptability was a strong trait in the American makeup and that it was being well used to improve performance in battle. American leaders were well trained and used their common sense and knowledge of the capabilities of their equipment to create the coordination of the separate elements of the Army’s combat arms into a unified force that was far greater than the sum of its parts.

No one who has studied World War II in Europe disparages German tactical acumen at this stage of the fighting or would argue that the American infantry in Normandy had achieved the level of skill and professionalism it later displayed in the fighting along the German border. But it is clear that it was improving rapidly. As one historian put it, the American Army’s adaptation was quick, and it adapted in a great number of ways.

Fortunately for America, the Axis leadership had its blind spots. Although a few Axis leaders like Rommel were aware as early as the fighting in Africa that American units improved rapidly in combat and should be taken seriously, an awareness of this trait did not permeate the thinking of Axis leadership.

Historian Carlo D’Este reflected that Mussolini viewed America as benefiting from a journalistic hoax that disguised the fact that it actually had the industrial capacity of a second-rate power. Hitler’s view of the American Army was even more negative.

It was not until German failure in the Battle of the Bulge that Hitler began to realize his error. America’s enemies have frequently failed to understand the strengths of the American character, in particular its ability to adapt, adjust, and rise above failure. There is no better example of American adaptability and the advantages that derive from it than the fighting for Hill 192.

The 2nd Infantry Division fought courageously and with skill for the rest of the war. By their devotion to duty, they more than lived up to their motto: “Second Infantry Division—Second to None.”

My uncle Pte Abraham Kalmikoff Silver Star. Purple Heart

Died 11th July

By the St Lo..Berigny road

May he and all his

Comrades rest in peace.

We all give thanks

That their sacrifice gave us the freedoms we have today

Bless You All

My uncle, Reynaldo Zuniga, from Mercedes, Texas, was a Platoon Sergeant with Co I, 3rd Battalion, 23rd Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division. He was wounded by German mortar fire on Hill 192. He returned to the Company but was again wounded at the siege of Brest in September 1944. This time the wound was almost fatal and the war was over for him.

My great uncle, Sgt. David J. Whyte of the 38th Infantry Regiment, was wounded in the assault on Hill 192 and died in England on July 20, 1944. We remember him on this Memorial Day for bravery in defense of his country.

I appreciate the benefit this website serves in continuing the story of our nation in WW2. My Grandfather Cpt Franklin Lee Cornwell died near St Lo France on June 12, 1944. He was in the 2nd Div, 23rd Regiment, Hq Co, 1st Bn. I will be continuing my search for more information about his story.https://centennial.legion.org/ohio/post95/1946/05/06/foody-post-95-renamed

I’m currently researching my great-uncle, John Podish, who was wounded at some point in July 1944 and died of his wounds October 13, 1944. He was part of the 2nd Div, 23rd Regiment. He was buried at Henri-Chapelle. He was only 23, not married and nor did he have children. Therefore, I am trying to get as much information and be his voice to honor his contribution to this country. Any information or guidence you can provide would be most helpful. Thank You!

Clayton,

Captain Cornwell and Major Spencer served together. They were close friends. They were together during an early assault on Hill 192 when explosions killed your Grandfather, and others, and severely wounded my Uncle. Uncle Grady’s book covers training in Wisconsin and Ireland, and I would not be surprised if there are mentions of your Grandfather there as well.

Hopefully you see this.

My dad Joseph J Pavelko 1st battalion 38th reg. And my uncle Donald Goddard 23rd reg. Both took part in the attack on hill 192 with the 2nd id . This is the first time I have heard the whole story. The only time I ever heard them talk about 192 was at the drive-in watching the longest day. Unfortunately for me I was too young to ask ask them to tell me more. They both passed before I realized their important contribution, thank you!

Don Pavelko, thank you so much for sharing the stories of your father and uncle! It is greatly appreciated. I am a co-founder of the project “Men of the 2nd Infantry Division” which tries to collect and preserve the stories of men who served in this famous Division during WWII. We are currently creating an online database of men of the 2nd Infantry Division and I am interested to learn more about your veterans of the 2nd ID. Please, could you contact me at our e-mail address: indianhead.roster@gmail.com I look forward to hearing from you.

My Dad, LT Gene Innocenti was a platoon leader in K Company, 3rd Battalion, 38th Infantry, in the taking of Hill 192 and was awarded a Bronze Star for meritorious achievement against the the enemy. He was later wounded in hedgerow fighting in July 1944 and spent the remainder of the war in England. I would not have been born in 1948

without his service to our country.

My Dad (Harold H Keller) was in the Navy in 1944. He was on a Yacht converted to a naval vessel on his way to the phillipine Ilands, I would like to know the name/number of the vessel and any info related to my dad and the vessel.

Dad, a member of the US 2nd Engineers, took part in a re-supply patrol during the Battle for Hill 192. He had to take charge of the patrol as night fell, because the officer in charge lost control of his senses. Dad let the patrol back to HQ successfully, and he later received the Bronze Star for his action.

My dad Sgt Egill Hanson was wounded on July 12 1944 at hill192. He was a squad leader in L Co 9th Rgt 2nd division. Thank you for the great article!! I am trying to do research on my dad’s unit so my kids will know what their grandpa did.

My Uncle Grady, Major Henry Grady Spencer, was married to my Dad’s sister Mary. In his elder years he wrote a book about his WW2 service called “Nineteen Days in June 1944”. He is the recipient of a Silver Star Medal for his gallantry during an early assault of Hill 192. He was seriously wounded and did not return to the war.

My dad, Pvt. John Joseph Carroll, was wounded in action on Hill 192. If I recall correctly, it was July 26, 1944. After recovering from his wound, he rejoined his unit before the Battle of the Bulge and the Ardenne Forest battle. I am trying to research the regiment/ company of which he was a member.