By John Domagalski

It was 7:25 am when Flight Captain William Motes brought his plane down for landing. The arrival of the American Airlines Convair on October 30, 1955, marked the beginning of the first day of regularly scheduled passenger service at Chicago’s new O’Hare International Airport. Hailed as an aviation milestone, the airport would soon become the world’s busiest.

The name O’Hare would eventually become instantly recognizable by millions of business and leisure travelers alike. Yet, few Americans know very much about the airport’s namesake, Lt.

Cmdr. Edward “Butch” O’Hare. A dedicated naval airman, O’Hare was a much-needed hero in the desperate early days of World War II in the Pacific. The O’Hare story is one of determination, heroism, gallantry, and sacrifice.

Edward Henry O’Hare was born on March 13, 1914, in St. Louis, Missouri, to parents of German and Irish descent. He was the son of wealthy attorney and businessman Edward J. O’Hare, who would later move to Chicago to become a horse racing promoter. Eddie, as the younger O’Hare soon became known, lived a comfortable childhood in the St. Louis area with younger sisters Patricia and Marilyn. As a youngster, he was fond of airplanes, swimming, and hunting. It was during summer visits to a friend’s riverfront property that O’Hare learned marksmanship and became a good shot by using cans and bottles for target practice with his .22-caliber rifle. In 1926 at the age of 12, O’Hare entered Western Military Academy in Alton, Illinois. Over the next four years, he played football and was the captain of the rifle team while earning honor roll grades and an excellent reputation.

Deciding on a career in the military, O’Hare entered the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, in 1932, appointed by Missouri Congressman John J. Cochran. While at the Academy, O’Hare played on the water polo team and picked up the nickname “Butch,” which would stay with him for the rest of his life. The editors of the Academy yearbook, The Lucky Bag, wrote of O’Hare as being both friendly and personable. “The possessor of a winning personality, Ed has found no trouble in making lasting friendships; he is always ready with a pat on the back when you need it most.”

Graduating in 1937 at the age of 23, Lieutenant O’Hare finished 255th in his Naval Academy class of 323. Although he desired to become an aviator, Navy policy of the time required all new officers to begin their careers on a surface ship. O’Hare was assigned to the battleship New Mexico for the required two-year tour of duty.

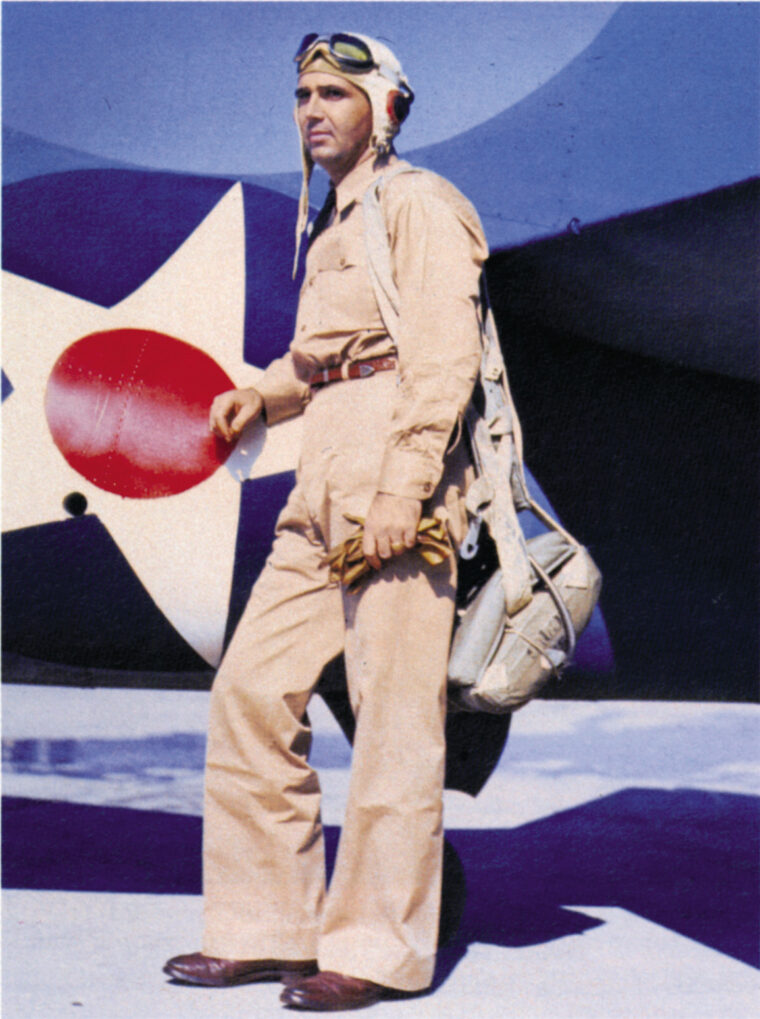

When his battleship duty was completed, O’Hare was free to pursue his interest in aviation. He entered flight school on June 9, 1939, at the Naval Air Station in Pensacola, Florida. During training he became both a skilled flier and expert marksman.

O’Hare graduated flight school as a naval aviator on May 27, 1940. He was assigned to Fighter Squadron Three (VF-3) aboard the aircraft carrier Saratoga, based in San Diego. The squadron was soon under the command of Lt. Cmdr. John Thach. A member of the Naval Academy class of 1927, Thach was an experienced pilot who had trained extensively in fighter tactics. The two formed an almost immediate bond. O’Hare’s aviator skills would continue to develop under Thach’s close instruction. He made his first carrier landing on July 24, 1940, landing a Grumman F3F-1 biplane fighter on the deck of the Saratoga. About a year later the squadron upgraded to the new Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter.

Flown by both Navy and Marine pilots, the Wildcat became the U.S. Navy’s frontline fighter during the opening years of the Pacific War. Although not as maneuverable as its nemesis, the Japanese Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighter, the Wildcat was built to absorb a fair amount of battle damage and had a powerful armament of four wing-mounted .50-caliber machine guns.

While home on leave in St. Louis, O’Hare met Rita Wooster. A native of Keokuk, Iowa, the 24-year-old Wooster was training to become a nurse at DePaul Hospital in St. Louis. The couple married on September 5, 1941, in Phoenix, Arizona, and took a honeymoon trip to Hawaii. They later became the parents of a daughter named Kathleen.

On December 7, 1941, the Saratoga was returning to San Diego from a retrofit in Bremerton, Washington. The planes and pilots of VF-3 were already on land at the North Island Naval Air Station when the news came of the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Planes and supplies were hastily loaded aboard as crew members scrambled about trying to ready the ship for sea. At 9:30 am on December 8, the Saratoga sailed into open water bound for Pearl Harbor. During the remainder of December, the carrier prowled the waters west of Hawaii and participated in a failed attempt to rush supplies to Wake Island.

January 11, 1942, found the Saratoga in the sights of the Japanese submarine I-6. Sailing about 500 miles south of Hawaii, the carrier was hit by one torpedo below the waterline on the port side, killing six of the crew and flooding several compartments. Severely damaged, the Saratoga was able to limp back to Pearl Harbor under its own power. The carrier was soon transferred back to Bremerton for permanent repairs resulting in its missing the upcoming Coral Sea and Midway battles. With the Saratoga out of commission for several months, VF-3 was transferred to its sister ship, the Lexington.

The beginning of 1942 brought little improvement to the American position in the Pacific. In the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack, the Japanese advance southward continued almost unchecked. The beleaguered American defense of the Philippines was crumbling. Good news was in short supply. American morale was low, and it was badly in need of a hero.

In the South Pacific, the Japanese bombed and attacked New Guinea and the nearby island of New Britain. Situated in the Bismarck Archipelago east of New Guinea and northwest of the Solomon Islands, New Britain occupied a strategic position. The island’s capital city of Rabaul was seized on January 23. Rabaul had a good harbor, and American intelligence soon learned that the Japanese were turning it into a major air and naval base with troops and supplies arriving on a daily basis. Once established, the base could be used as a staging point for further advances south and east.

American Vice Admiral Wilson Brown decided on a daring attack designed to disrupt the progress of Japanese base building on Rabaul. A Naval Academy graduate of the class of 1902, Brown had commanded a destroyer in World War I and served in various postwar capacities before attaining the rank of vice admiral on February 1, 1941. In command of a task force built around the Lexington, Brown planned to elude Japanese patrols by traveling up the eastern side of the Solomon Islands to a position just east of the island of New Ireland.

From that launch point, the carrier’s planes would then be able to fly 125 miles west to surprise the unsuspecting Japanese at Rabaul. It was a bold and risky strategy. The Lexington had to reach the launch point undetected. The Japanese carriers Akagi, Kaga, Zuikaku, and Shokaku were thought to be operating somewhere in the South Pacific. An assortment of battleships and cruisers were likely at the Japanese island fortress of Truk to the north. At the time of the attack, the Lexington would be perilously positioned between Rabaul and Truk. Strict radio silence would have to be maintained once the Lexington started her journey.

Accompanying the Lexington on the raid were the heavy cruisers Minneapolis, Indianapolis, Pensacola, and San Francisco along with 10 destroyers. On the morning of February 20, Admiral Brown’s task force was well into enemy waters moving at high speed toward the designated launch point. In the Lexington’s ready room, Butch O’Hare and the other pilots of VF-3 listened intently as Thach used a chart to outline the mission. “We’ll launch the strikes here about 125 miles from Rabaul. Our first job is to take care of any snoopers that may show up during the next 10 or 12 hours. We don’t want them sending any fix back to Rabaul.”

By midmorning the task force was about 350 miles east of Rabaul, not yet at the launch point. At about 10 am, the Lexington spotted an unidentified plane approaching the task force. It likely was a long-range Japanese search plane intent on radioing the task force’s exact position back to its base. Squadron leader Thach, his wingman Ensign Edward Sellstrom, and two other Wildcat fighters raced through the clouds to the scene.

“Suddenly the cloud opened right in the center,” Thach said of the encounter. “There, right under me, was a Mavis, a four-engine patrol bomber bigger than the Pan-American Clipper. I don’t know which one of us was most surprised.”

Both planes soon disappeared back into the thick rain clouds. “At last I dimly saw a huge shape leaving the rain squall. I never lost him again. I overtook him with the other fighter protecting my tail and I gained position for attack,” Thach recalled. Both Wildcats opened fire on the much larger Japanese flying boat. “We continued in and made our firing run and I saw that I had hit his fuel tanks, for gasoline was spraying astern of him.”

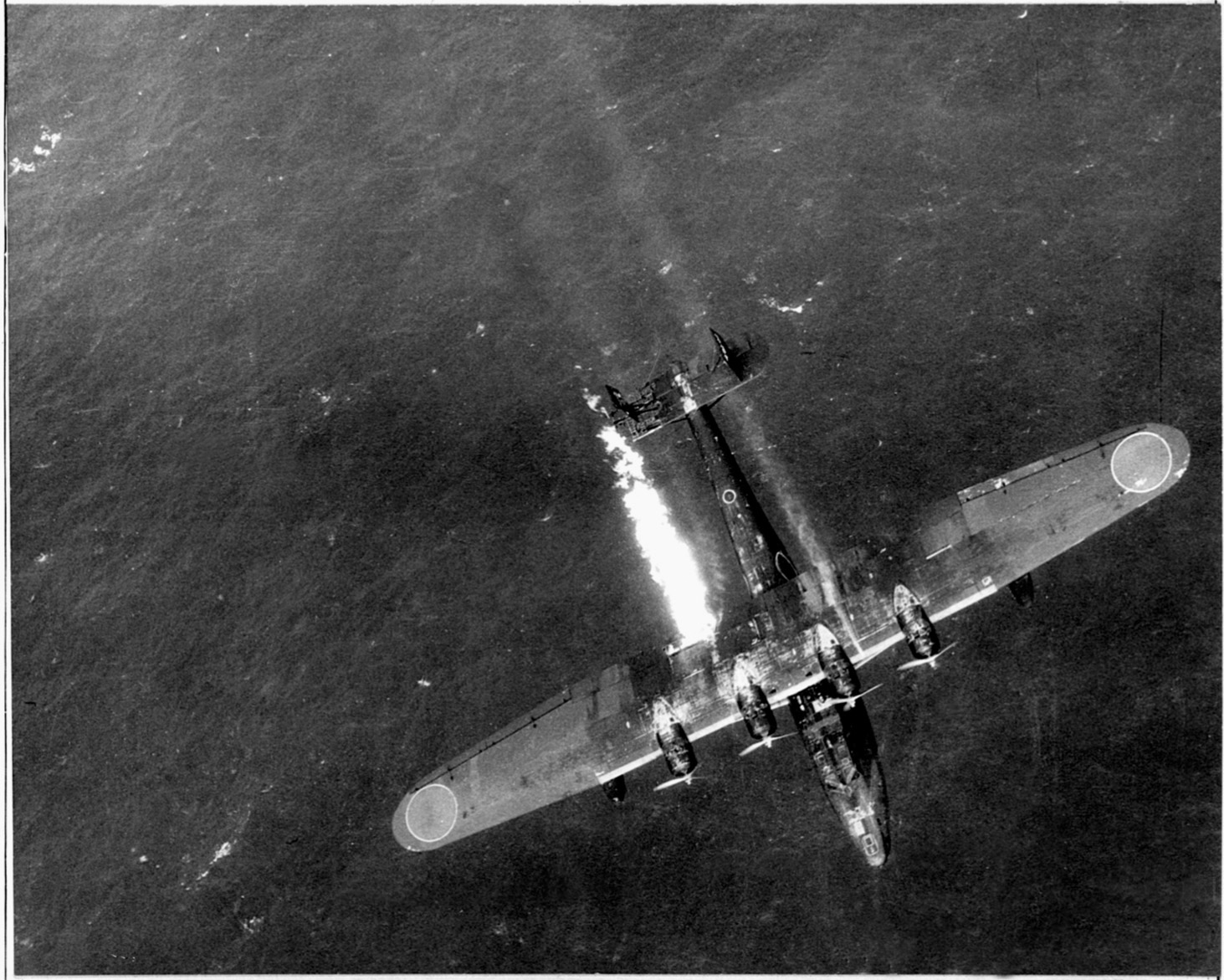

Both fighters immediately turned and came in for a second pass. “Our bullets ignited him for he suddenly caught fire. Great white sheets of flame from the streaming fuel spread out behind him and he began spinning down into the sea.”

Thach screamed into his microphone, “I got him!” It was the first plane to be shot down by airmen from the Lexington.

While Thach and his wingman took care of the first Japanese scout, other Wildcats had located and shot down a second flying boat. The victories were bittersweet as the scouts had successfully notified their base of the approaching American carrier. The American flyers returned to their carrier and over a quick lunch wondered about the future. Some type of Japanese attack was now all but certain.

As the task force continued at full speed toward Rabaul, the Lexington prepared for battle. Captain Fredrick Sherman called the crew to battle stations. Antiaircraft guns were manned and made ready for action. As a precaution, the carrier maintained a protective fighter cover of six Wildcats at all times.

In early afternoon, the Lexington’s radar picked up enemy planes approaching the task force from 25 miles away and closing fast. The planes were twin-engine Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” type bombers, each carrying two bombs. The formation of nine land-based planes had come from Rabaul, the very base the Lexington was planning to attack.

Thach once again led his Wildcat fighters into battle. In addition to the normal patrol of six fighters, Thach recalled six additional Wildcats that had just been relieved and were preparing to land. He ordered O’Hare and wingman Lieutenant Marion Dufilho to stay over the Lexington in reserve while the rest off the fighters went off to meet the attackers.

The ensuing battle lasted almost 10 minutes. “When first seen they were 12 miles out at 12,000 feet flying in a slight dive toward the 10,000 foot level,” recalled Thach. “They had guns in the turtle back, in the tail position, and in the nose—machine guns and 20mm cannon.” The fighters dove in for the attack. “The first time two of our fighters pressed their triggers, two Jap bombers fell.”

The American fighters soon shot down six of the bombers. Two additional attackers were damaged and shot down by the Lexington’s antiaircraft guns. The remaining bomber was damaged as it sped away from the scene of the attack. No bombs fell close to the Lexington, but two Wildcats went down in the battle with one pilot, Ensign J. Woodrow Wilson, lost.

In the aftermath of the battle some of the Wildcats gave chase to the last remaining bomber. Others, extremely low on fuel, began to land on the carrier. O’Hare and Dufilho maintained their protective position over the Lexington. The situation at that moment was less than ideal for providing protective fighter cover should another attack occur.

Suddenly, the alarm sounded again. The Lexington’s radar had picked up a second set of attackers closing in fast from the opposite side of the task force. This group of attackers consisted of nine bombers of the same Mitsubishi type flying in three V formations. At the time of contact these were much closer to the carrier than the first group and had a clear path to the Lexington.

O’Hare remembered later: “This time we weren’t quite ready for them, since most of the fighters were being refueled and getting ammunition. Thach and another plane were off chasing what was left of the first Jap flight and I was alone with one other plane over the ship.” As the two Wildcats turned to face the attackers, Dufilho’s guns jammed.

Butch O’Hare was now on his own to face the nine approaching bombers. The crew of the Lexington watched the developing battle in horror, hoping that the attacking planes could be stopped.

Making his first pass, O’Hare fired at the last two bombers on the right side of the formation. “I had fired at the starboard engine in each ship and kept shooting each time till they jumped right out of their mountings,” he said. “This caused both of these planes to veer round to the starboard and fall out of the formation.”

O’Hare then circled his Wildcat around and came at the formation from the opposite side, aiming his guns at the nearest plane. “I fired into the port engine of that plane and saw it jump out,” he continued. “I pulled away slightly while this third plane skidded violently and fell away, then went back in and fired into the trailer of the middle V, still shooting at the engines.” The bomber quickly became engulfed in flames as it spiraled down toward the sea.

The remaining Japanese planes, continuing to close in on the Lexington, were now in range of the ship’s antiaircraft guns, which began to fire. Ignoring the danger, O’Hare pressed in for a third pass and knocked a fifth bomber out of the sky. He was able to damage one more enemy bomber before running out of ammunition. “The last Jap I went after I could have downed except my gun stopped after 10 rounds when I ran out of ammunition,” he said. The entire action lasted about four minutes.

Help now arrived on the scene in the form of Thach and several of his Wildcat pilots who witnessed the initial battle but were too far away to help. “How O’Hare survived the concentrated fire of this Japanese formation I don’t know,” noted Thach. “Each time he came in, the turtle-back guns of the whole group were turned on him. I could see the tracers curling all around him and it looked to us as if he would go at any second.”

Thach’s fighters chased away the remaining Japanese planes, but not before they pressed home their attack. One damaged Betty approached the Lexington from astern. Cruisers and destroyers opened fire with an assortment of antiaircraft guns, but the plane kept coming. The hail of gunfire finally brought the plane down in a plume of smoke about 200 yards from the stern of the carrier.

The Wildcats, along with the Lexington’s guns, sent three more bombers down in flames. Although several bombs fell within 50 yards of the Lexington, the carrier suffered no damage. All told, eight of the nine attacking bombers were shot down with O’Hare claiming five kills.

The crew of the Lexington cheered wildly at the demise of the Japanese bombers. Admiral Brown noted, “I even had to remind some of my staff that this was not a football game.” In the aftermath of the air battle, the admiral cancelled the mission to attack Rabaul. Sixteen Japanese planes in all, including the flying boats, were shot down by the Lexington and its airmen. The hero of the day was Butch O’Hare. O’Hare’s Wildcat touched down to a hero’s welcome on the flight deck of the Lexington. The modest O’Hare only desired to reload and head back up into the sky. “I’m okay,” he said as he climbed out of the cockpit. “Just load those ammo belts and I’ll get back up. But first I want a drink of water.” While he did not go back up into the air that day, O’Hare did go up to the bridge to receive formal congratulations from Admiral Brown.

Upon returning to Pearl Harbor, O’Hare was soon ordered back to Washington. Facing a fury of reporters, he explained of the air battle, “There wasn’t much to do but to shoot ’em.”

Thach submitted a recommendation that O’Hare be given the Medal of Honor.

At a White House ceremony, O’Hare along with his wife Rita, stood proudly as he received the award. President Franklin D. Roosevelt called the action, “One of the most daring, if not the most daring, single action in the history of combat aviation.”

The official citation read in part, “For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in aerial combat, at grave risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty .… Having lost the assistance of his teammates, Lt. O’Hare interposed his plane between his ship and an advancing enemy formation of nine attacking twin-engine heavy bombers .… Despite this concentrated opposition, Lt. O’Hare, by his gallant and courageous action, his extremely skillful marksmanship in making the most of every shot of his limited amount of ammunition, shot down five enemy bombers and severely damaged a sixth before they reached the bomb release point.”

Butch O’Hare spent the subsequent months touring the country and receiving a hero’s welcome at every destination. In the course of his travels, he visited the Grumman Aircraft Company in New York, where a new American fighter plane, the F6F Hellcat, was under development. He advised the designers on what American airmen needed most, “A plane that will go upstairs faster.” What O’Hare longed for most was a return to action in the Pacific.

In June 1942, the hero O’Hare returned to the Pacific as commander of Fighter Squadron Three. Now based at Puunene Naval Air Station on Maui, the squadron had suffered serious losses in the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway and was lacking experienced pilots. In February 1943, the squadron departed for North Island Naval Air Station near San Diego, where O’Hare was assigned the task of training new pilots to get the unit up to battle speed.

He was remembered by the pilots he trained as both an effective leader and a good teacher. One such pilot, Lieutenant George Rodgers, remembers O’Hare as a just one of the guys. “He worked the squadron hard, but he ran it with a sense of humor that helped him and us to take it.”

After being promoted to lieutenant commander, O’Hare and his rebuilt fighter squadron returned to Pearl Harbor in the summer of 1943. Soon afterward, Fighter Squadron Three was redesignated as Fighter Squadron Six (VF-6). On August 5, 1943, VF-6 was assigned to the aircraft carrier Independence.

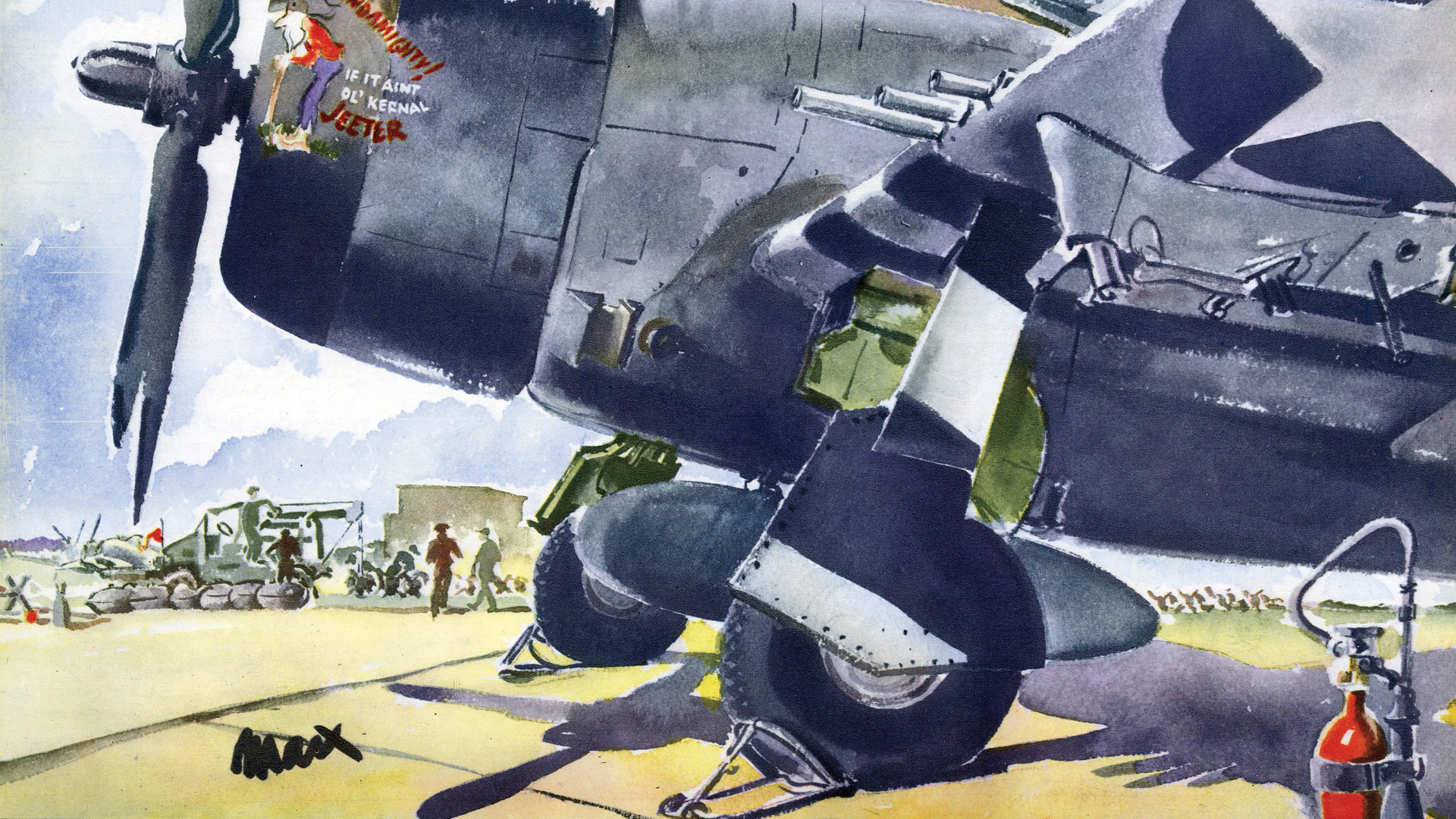

Like most fighter squadrons, VF-6 was now flying the new Grumman F6F Hellcat fighter. As the successor of the Wildcat, the Hellcat was designed to incorporate the lessons of combat. Improvements in speed and climb, along with six wing-mounted .50-caliber machine guns, meant the Hellcat was more than a match for the Zero in combat.

In September, O’Hare and VF-6 returned to combat. The U.S. Navy now had a new weapon in the Pacific War, the Essex-class aircraft carrier. Larger and faster than their predecessors, these fleet carriers were organized with battleships and cruisers into fast-moving task forces capable of striking deep into enemy-held territory. The new carriers were put into action in a series of air attacks on Japanese-held islands.

The first to be attacked was Marcus Island, located about halfway between Midway and Okinawa. The Independence joined the new carriers Yorktown and Essex in a task force under the command of Rear Admiral Charles Pownall. On September 1, the carriers launched six strikes against the island. It was O’Hare’s first combat since his days aboard the Lexington. The Japanese were taken by complete surprise, and much of their shore installations were destroyed in the attack. O’Hare was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his efforts.

The next attack involved the largest American carrier task force assembled to date. The carriers Essex, Yorktown, Lexington, Cowpens, Belleau Wood, and Independence sortied from Pearl Harbor under the command of Rear Admiral Alfred Montgomery. On October 5 and 6, the task force launched six air strikes against Wake Island. About 375 pilots, including O’Hare, participated in the attack. The initial strike group was intercepted by an assortment of 30 Japanese planes. In the air battle that followed, O’Hare shot down one Zero and assisted in the downing of a Betty bomber.

By late 1943, the tide of war had turned against the Japanese in the Pacific. The American strategy called for a two-pronged advance across the Pacific toward Japan. The first drive would originate from the south moving northwest from the Solomon Islands through New Guinea and ultimately arriving in the Philippines. The second offensive would be launched west from Pearl Harbor and target Japanese strongholds in the Gilbert, Marshall, and Marianas Island groups. The two prongs would ultimately converge for a final assault on Japan.

The Gilberts were first targeted by the American forces in the Central Pacific. Located approximately 2,100 miles southwest of Hawaii and 1,000 miles northeast of Guadalcanal, the islands represented a key Japanese base that could not be bypassed. The main target of the attack was the island of Tarawa, the location of a major Japanese air base. Makin, a smaller island to the north, would also be assaulted.

In support of the operation was the largest American naval armada assembled to date. Converging on the Gilberts was an invasion fleet of 200 ships, 35,000 troops, 6,000 vehicles, and almost 120,000 tons of supplies. Leading the attack was Task Force 50 of the Navy’s Fifth Fleet. It comprised six fleet carriers, five light carriers, and almost 700 planes roughly divided into four task groups.

The northern carrier group (Task Group 50.2) consisted of the veteran carrier Enterprise, light carriers Belleau Wood and Monterey, three battleships, and six destroyers. Under the command of Rear Admiral Arthur Radford, the task group’s principle role was to patrol the area north of Tarawa to protect the invasion forces from a potential counterattack. A secondary mission was to provide supporting airstrikes for ground forces as needed.

Air Group Six, under the command of O’Hare, was aboard the Enterprise. The air group consisted of Bombing Squadron Six (VB-6), Torpedo Squadron Six (VT-6), and Fighter Squadron Two (VF-2). O’Hare had a total of 90 planes under his command.

Operation Galvanic, the invasion of Tarawa, began on November 20, 1943, after the island had taken a heavy pounding from naval gunfire and air strikes. After three days of brutal fighting, organized Japanese resistance on Tarawa ended. Although the land battle was almost over, the attacks on American ships in the area continued.

Using airbases several hundred miles north in the Marshalls, the now familiar Japanese Betty bombers, armed with torpedoes, traveled south to attack American carriers. After sustaining heavy losses to Hellcat fighters and antiaircraft guns during daytime attacks, the Japanese turned to night torpedo attacks.

Aboard the Enterprise, O’Hare lectured his pilots on the new Japanese tactics. “They know it takes torpedoes hitting below the waterline to sink our ships permanently. And the only time to sock their fish home is at night when they can avoid our fighters. Once the Japs get set on this night business, it’s going to be curtains for us.”

The Japanese strategy called for using scout planes to locate American carriers by marking their approximate positions with flares. The light would allow other Japanese pilots to see the large ships by silhouette and press home their attacks. Although American ships could see the attacking planes on radar, antiaircraft fire was generally avoided as it could easily give away a ship’s position. On the night of November 25, one Betty came to within a few hundred feet of the Enterprise. Torpedo wakes were being sighted on a nightly basis, and it was only a matter of time before a torpedo hit its target.

Butch O’Hare was getting impatient and wanted action. “Last night they launched at least five fish. They’ll be back to do the job right. I don’t intend to sit here doing nothing. We’re going to find a way to bust up this night attack business if it’s the last thing we do.”

O’Hare proposed to break up the night attacks using carrier-launched night fighters. His plan called for a TBF Avenger torpedo bomber to be launched at dusk equipped with an extra fuel tank and small radar set. Once the long-range radar on the Enterprise detected enemy bombers, two Hellcat fighters would be launched to join the Avenger. To avoid becoming disoriented, the three planes would stay together, flying in close formation.

The fighter direction officer aboard the Enterprise would direct the trio to the general area of the attackers. Using its smaller radar set, the Avenger would then take over directing the Hellcats to their targets. Once close enough, the targets could be visually identified by engine exhaust streaks, and the Hellcats could attack from behind. The fighters should have enough fuel to return to the carrier for a landing at first light.

Having tested close formation night flying during training, O’Hare was convinced that his plan would work. However, the risks were great and potentially catastrophic. Planes could easily collide while flying in close formation at night. A pilot could become disoriented in the darkness and crash into the sea. Carrier landings were dangerous enough during daylight hours. Could it safely be done at night if needed?

O’Hare’s plan would be put into action on the night of November 26. Just finishing dinner when the alarm sounded, he motioned off a dish of ice cream as he headed toward the ready room. “No thanks,” he told the mess attendant. “Keep it cold until I get back tonight.” The long-range radar had picked up a large number of Japanese planes heading for the task group.

O’Hare’s plane captain wished him luck as he climbed into the cockpit of the Hellcat. O’Hare replied, “Hell, we don’t need luck with these cookies.” The first night fighter operation was about to begin.

Lieutenant Commander John Phillips, leader of VT-2, piloted the radar-equipped Avenger that night. His crew consisted of Lieutenant Hazen Rand as radar operator and Aviation Ordnanceman Alvin Kernan manning the tail gun. Butch O’Hare piloted one Hellcat, while Ensign Warren Skon served as his wingman. At 6 pm, the three planes were catapulted off the flight deck of Enterprise and disappeared into the twilight.

The first-ever night air battle was filled with confusion. The Hellcats became separated from the Avenger almost immediately as the fighter direction officer vectored the planes toward the approaching Japanese formation. Phillips recalled the difficulty of trying to keep the planes together. “We had difficulty sticking together when it got dark. But we were lucky and were joining up when we ran into the Japs rendezvousing.”

Closing range to make visual contact, the Avenger came across a formation of Bettys and opened fire. Phillips set his sights on one bomber and fired with his two wing-mounted .50-caliber machine guns. Kernan sprayed the same plane with machine-gun fire as the Avenger passed it by. The bomber caught fire, leaving a red streak in its wake as it veered out of formation and began its descent into the black sea below.

Phillips shouted into the radio, “I got me a Jap!” The Avenger soon made visual contact with a second bomber and opened fire. The second Betty caught fire and streaked down toward the ocean. Taken by surprise, the Japanese gunners began to fire at random in hopes of hitting an American plane. One Japanese bullet hit the Avenger, wounding Rand in the foot. The torpedo attack appeared to be disrupted.

O’Hare’s voice came across the radio as the trio of American planes struggled to get together to coordinate an attack. “Phil, you’d better turn on your cockpit light. It looks like we’re in a thousand Japs and I want to make sure I’m drilling the right guy.” Attempting to pull together, all three American planes had their lights on for a brief time.

O’Hare radioed to Skon, “You take the side you want.” The planes finally came together into one formation, the Avenger in the center with O’Hare flying on the starboard side and Skon on the port.

Suddenly, a fourth plane approached behind O’Hare’s Hellcat as if to join in the formation. Phillips shouted into his microphone, “Butch there’s a Jap joining up on you, coming in high! I’m instructing Kernan to shoot.” Kernan saw the long black plane coming up from behind and opened fire, his machine gun lighting up the night sky with tracer bullets. At the same instance the Betty began to fire at O’Hare. For a brief moment, both planes were firing.

The Betty appeared to be hit as it turned away, disappearing into the darkness. A few moments later, an explosion occurred just over the horizon. Kernan thought he saw O’Hare’s plane turn down, reappear for a brief moment, and then disappear for good. Phillips called out to O’Hare, “Butch this is Phil. We got him! Butch this is Phil over!” There was no answer.

Skon reported seeing gunfire from the Betty before observing O’Hare’s plane drop down out of sight. “I saw tracers around his plane. I saw it sheer off and drop below us.” Skon pulled his Hellcat out of the formation in a failed attempt to locate O’Hare.

Seeing the action from a different angle, Phillips later recalled, “While I was watching the Jap burn I saw something drop straight off and into the water, making a big splash. Then I thought my God that may be Butch.”

After the battle, Rand recalled his observations: “I saw a fourth plane’s guns blinking red, and he was shooting at Butch while our gunner, Kernan, was shooting at the Jap. Then Butch’s light went off. I looked again and he was gone.” Unable to locate their leader, the remaining two planes headed for home.

Both Phillips and Skon made tense but safe night landings on the Enterprise. The Japanese attack had been thwarted, although a few bombers managed to launch their torpedoes near the Belleau Wood. For the men on the Enterprise, the grim news slowly set in that Butch O’Hare was missing.

The search for O’Hare commenced at dawn on November 27. A large search grid was established, allowing for a 25-mile drift from the approximate point of O’Hare’s downing. Equipped with dye markers and emergency supply kits, planes from Tarawa joined carrier planes from Task Force 50 in searching almost 2,000 square miles.

No trace of O’Hare or his plane was ever found. Edward “Butch” O’Hare, fighter ace, war hero, son, husband, and father, was missing in action and presumed dead. Recommending O’Hare for a second Medal of Honor, Admiral Radford said, “Butch, with accompanying planes, saved my formation from certain torpedo hits.” In the end, all the participants of the night action would be awarded the Navy Cross.

What exactly happened to O’Hare has been the subject of much speculation. Ensign Skon would later summarize his beliefs: “I’m certain in my own mind that he was hit directly. We had perfect radio communication. Butch would have talked to us as his plane fell if he had not been directly hit.”

The most widely held belief seems to be that O’Hare was brought down by a short but lucky burst of machine-gun fire by the forward gunner in the Betty. Since no Japanese airman claimed to have shot down an American plane that night, the gunner probably did not even know what he had accomplished.

Other brave American pilots came forward to continue the night fighting work that O’Hare had started. During the remainder of the war, carrier planes flew 164 night missions and shot down 103 enemy planes. Six more American pilots would be lost in night combat.

O’Hare was officially declared dead almost one year after his disappearance. He was credited with shooting down 6 and a half Japanese planes in combat. His decorations included the Medal of Honor, Navy Cross, two Distinguished Flying Crosses, and the Purple Heart.

President John F. Kennedy stepped into bright sunshine and an unseasonably warm temperature as he walked out of the United Airlines terminal building at O’Hare International Airport. The first order of business during the brief presidential visit to Chicago on March 23, 1963, would be a formal airport dedication ceremony. The president laid a wreath at the base of a plaque honoring the airport’s namesake before stepping up a platform overlooking the crowd of dignitaries and well wishers.

A World War II hero himself, Kennedy spoke of the White House ceremony in 1942 in which O’Hare was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Roosevelt. “The tragically short life of Lieutenant Commander Edward H. O’Hare came to an end only 18 months later,” Kennedy remarked, “but his name lives on in the great international airport that we dedicate here today.”

The airport remains a lasting tribute to an early American hero of World War II. n

First-time contributor John Domagalski is a marketing manager for a major corporation and resides in the Chicago area.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments