By Eric Hammel

After the Japanese stopped resisting in the skies over Rabaul and pulled their aircraft out of the Solomons and Bismarcks battle area in mid-February 1944, it began to appear that U.S. Marine Air’s glory days were over.

From August 20, 1942, until February 17, 1944, Marine Air had carved a significant, perhaps central, position for itself in the prosecution of the grinding war in the South Pacific. Several thousand Marine pilots and bomber crewmen had taken a leading role in breaking the back of Japanese air power in the Pacific—by downing many hundreds of Japanese bombers and fighters; by killing many hundreds of the best pilots and air crewmen the Empire of Japan would ever train; and, through a relentless war of attrition, by forcing resource-poor Japan to give over vast portions of her limited industrial capacity to constantly replacing losses born through increasingly one-sided aerial combat and the unceasing need to repair bomb-battered air bases and replace all manner of military resources.

In the end, the perpetual grinding action of the Solomons and Bismarcks air campaigns had defeated the Imperial Navy’s best effort to hold the line in what Japan referred to as the South Seas Area. The bottomless pit of losses had to be sealed, and the only way the Japanese could seal it was by withdrawing from it.

Suddenly, after 18 months of constant confrontation, the air war in the strategically vital region came to an abrupt and unexpected halt. Many hundreds of U.S. Marine, Navy, and Army Air Forces warplanes organized into a complex array of combat commands ceased to have a significant role to play. Moreover, in November 1943, the main thrust of the Pacific War had moved to the small islands and far-flung atolls of the Central Pacific areas.

The type of attritional warfare at which Marine Air had come to excel was not a factor in the new area of operations; the distances were too great for a grinding attritional war undertaken by the short-range fighters and light bombers in the Marine arsenal, the battles were too brief and needed support for only limited periods, and the Japanese simply did not react with the all-out aerial counteroffensives that had characterized the much longer campaigns in the Solomons and Bismarcks. In short, there was no aggressive, essential role in the Central Pacific that matched or required Marine Air’s hard-won experience and rather specialized capabilities.

Now, from early 1944, thanks to the Allies’ successful bypass strategy, it appeared that Marine Air would be increasingly relegated to a minor role in the Pacific Theater’s many operational backwaters.

Marine Aviation Against Rabaul

The ultimate backwater in early 1944 remained Rabaul and several bypassed Imperial Navy airfields in the northern Solomon Islands, chiefly at Kahili and Buka-Bonis. Although bypassed and to a degree inaccessible from other Japanese bases, these airfields and their supporting infrastructure had to be kept in a nonoperational status. Even though the big war had passed them by, these bases—especially Rabaul—were manned by large garrisons that rather doggedly tried and succeeded at maintaining the airfields at some level of operational readiness.

Although deemed of little importance by increasingly confident Allied commanders, the bases needed to be visited on a regular basis by bombers capable of destroying what little the Japanese garrisons were capable of building back up. To the degree that Japan wanted to sink more matériel into the ongoing maintenance of her bypassed South Seas bases, the bombing campaign had an ongoing if small impact in the war against the empire’s industrial and economic infrastructure long before Allied bombers could reach Japan’s factories.

So Rabaul was surrounded and cut off by a network of Allied air bases that were manned in large part by the bulk of Marine Air assets that had been and still were being deployed to the Pacific Theater. These assets were the end product of training and procurement programs that achieved maximum efficiency in the United States––just as the need for Marine Air’s unique war-driven capabilities precipitously diminished in the suddenly quiescent South Pacific.

From February 1944 onward, Marine Air formed the backbone for attritional bombing missions against Rabaul. Bombing attacks were mounted almost daily. Targets were hit, and some Marine aircraft were downed by Japanese antiaircraft fire, but the gunfire and operational accidents were about the only elements of danger posed in a campaign in which the Japanese did not otherwise resist.

Withering on the Vine

There was virtually no useful role for Marine Air in the Gilbert or Marshall Islands, which fell to U.S. Marine and U.S. Army infantrymen in late 1943 and early 1944. Marine air groups composed of fighters and light bombers were deployed to the newly captured Central Pacific bases, but their role was purely defensive—to stand against rare attacks by Japanese bombers, and to help co-located U.S. Navy and Army Air Forces patrol bombers track and pursue the odd Imperial Navy submarine that ventured into the area.

Marine PBJ medium bombers (the same as Army Air Forces B-25s) arrived in the South Pacific at the end of January 1944 and went into action against Rabaul in mid-March. The PBJs had adequate range to have been useful in bypass missions and, indeed, pre-invasion bombardment regimes that were being undertaken by then in the Central Pacific by identical island-based Seventh Air Force B-25s, but apparently any notion to deploy any of the new Marine PBJ squadrons to the battle area was quashed; all the PBJs were used against Rabaul.

Marine Air played a rather small and purely defensive role in the Central Pacific through the end of the war. Beginning in the Marshalls, Marine light bomber squadrons undertook purely routine attacks against bypassed Japanese bases that came within their range from a growing network of island airfields. As in the South Pacific, there was some small danger posed by antiaircraft guns, but aerial opposition was nil. Most losses were the result of operational accidents.

Following the withdrawal of Japanese defensive fighters from Rabaul on February 17, 1944, Marine fighter action in the South Pacific all but ceased. During the rest of February, hitherto extremely busy Marine F4U Corsair pilots downed just four Imperial Navy aircraft in the region, and a Marine night fighter crew downed one other, in only three days of action. In March, action on just four days produced five victory credits. And there were just two others in the region through the end of the war: a VMF(N)-531 night fighter crew downed a floatplane near Matupi on May 11, 1944; and a VMF-222 F4U pilot downed an Imperial Navy fighter over Kavieng, New Ireland, on June 13, 1944. Otherwise, thousands of Marine fighter sorties over the region between March 15, 1944, and September 1, 1945, reaped no fruit whatsoever.

In the Central Pacific, from November 1943 through the end of November 1944, Marine fighter pilots accounted for 11 aerial victories in just three encounters: on March 26, Marine F4U pilots from VMF-113 downed eight Imperial Navy fighters over the Japanese air base on Ponape Island, in the Marshalls; on April 14, VMF(N)-532 night fighter pilots downed two medium bombers over Eniwetok; and on October 31, a VMF(N)-541 night-fighter pilot downed a floatplane over Peleliu.

In a way, the bypass strategy, which was designed to cause vast Japanese resources to “wither on the vine,” came perilously close to causing the Marine Corps’ enormous investment in its aerial arm to wither on the vine as well. Marine Air, from mid-February though November 1944, played a useful role in the Pacific, but not a vital one. There was a plan in motion to base Marine squadrons aboard aircraft carriers—so they could provide close air support for Marine landing forces in future island battles—but this small program was late getting started and would never amount to a great deal because the Navy’s own burgeoning air arm had first call on the carriers. In sum, Marine Air really had no means in 1944 to support Marines.

Well then, thought the Marine Air general who was overseeing the air war in the South Pacific backwater, how about supporting U.S. Army troops—in new ways for which Marine Air was uniquely organized and qualified? And so began the movement of numerous Marine combat squadrons from the backwater to the forefront. The place was the Philippines, and the time would be early 1945.

Marines to the Philippines

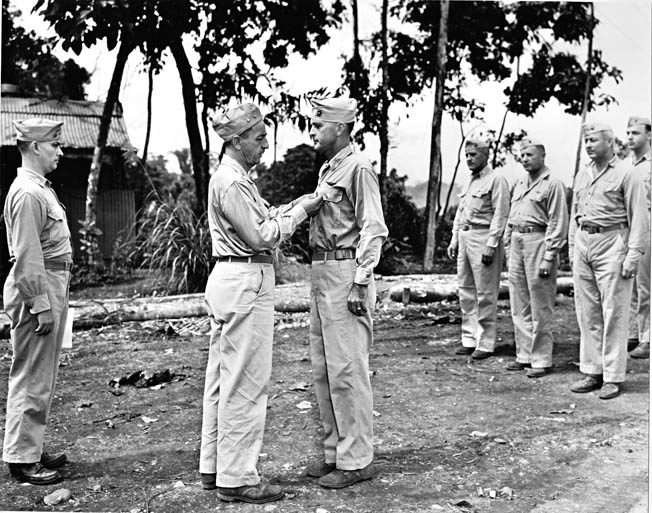

The involvement of Marine Air in the Philippines was the brainchild of Maj. Gen. Ralph Mitchell, who in mid-1944 was serving concurrently as commanding general of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing (1st MAW) and Aircraft, Northern Solomons. Mitchell knew that the headquarters of General Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area force was planning the invasion of the Philippines at Mindanao, and he went to sell the Southwest Pacific commanders and planners on the many advantages he saw in their using his well-trained, enthusiastic, combat-experienced Marine airmen.

At the time, no role could be envisaged for Marine Air in the Philippines, but as the invasion date neared, it was demonstrated to the planners that the southern and central Philippines were not as well defended as had been previously thought. Thus, MacArthur and his staff opted for a bold strike directly to the heart of the Philippine Islands, at Leyte, in the center of the archipelago.

The difference this decision made to Marine Air was based on distance. Mindanao, the original invasion target in the southern Philippines, was marginally within range of some Allied fighters based in New Guinea and nearby islands. But Leyte was not. So, in addition to acquiring fighter bases in the Palau and Molucca Islands, halfway between New Guinea and Mindanao, the Allied planners decided to hedge their bets and employ Marine fighters and light bombers to supplement the U.S. Army Air Forces air groups that would be available from the U.S. Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces.

The decision to temporarily bypass Mindanao in favor of invading Leyte was taken on September 15, 1944, and the landing date was set for October 15—two months earlier than the anticipated Mindanao invasion. On September 22, MacArthur’s Far East Air Forces announced that it had decided to add seven Marine dive-bomber squadrons to the roster of Army aviation units to be employed in the Philippines.

And on October 10, Colonel Lyle Meyer, the commanding officer of Marine Air Group 24 (MAG-24), was told by 1st MAW headquarters to get ready to support U.S. Army ground forces in the Philippines. A short time later, the MAG-32 headquarters, then in Hawaii, was ordered to assume control over the 1st MAW’s three remaining dive-bomber squadrons, also for duty in the Philippines. Colonel Clayton Jerome, who was serving at the time as the chief of staff for Aircraft, Northern Solomons, was given command of MAG-32 for the upcoming operation.

Training For Close Air Support

Planning for the entry of Marine Air into a new theater overseen entirely by U.S. Army forces fell to Lt. Col. Keith McCutcheon, the MAG-24 operations officer. And time was short. In addition to his considerable planning skills, McCutcheon was a particular enthusiast and expert on the emerging role for Marine Air of providing close air support for ground troops. While Marine Air had claimed an expertise in this realm dating back to 1927, actual experience and results had been unimpressive throughout the long Solomons campaign of 1942 and 1943. Indeed, it was not until late 1943 that an actual classic close-air ground-support mission was run by Marine Air, on Bougainville.

Nevertheless, McCutcheon had done the studies and seen what needed to be done. Just about the time he was tabbed with the job of planning the entry of Marine Air into the Philippines, he completed the writing of the Marine Corps’ first doctrinal paper on procedures for close air support of ground troops, and training was just about to get under way. Of course, the period McCutcheon had originally set aside for training Marine airmen and ground air-control teams had to be shortened. It lasted from October 13 to December 8, 1944, and was as much a test bed for McCutcheon’s doctrine as it was a training course. All in all, it was a busy period in which impressive results were attained.

By the end of November 1944, everything was moving along rapidly as planned. But just as MAG-24 and MAG-32 had nearly completed their training, the planned entry of Marine dive-bombers into the Philippines was upstaged by an answer to a call for urgently needed fighters.

The Invasion of Leyte

Following intense pre-invasion bombardment by the U.S. Army Air Forces’ land-based bombers and U.S. Navy carrier aircraft, the U.S. Sixth Army invaded the central Philippines at Leyte on October 20, 1944. The landing was a complete success, and most D-day objectives were taken without much of a struggle. Among the early prizes was Tacloban Airfield on Leyte’s west coast opposite Samar Island. Dulag Airfield fell on October 21, as did three smaller airstrips near Burauen. Once rehabilitated and expanded, these bases and several new ones to be built by Army engineers would form the main structure for air support in the region.

Japanese air reaction to the invasion began massively on October 23 and soon resolved itself into the intense Battle of Leyte Gulf, which lasted until October 26 and ended in a complete American victory––a monumental strategic windfall. Nevertheless, on October 25, Japanese kamikaze aircraft making their combat debut took out several U.S. Navy carriers and made refugees of the carrier air groups.

It so happened that Maj. Gen. Ralph Mitchell, the 1st MAW commanding general, was inspecting Tacloban Airfield at the time the carrier fighters and bombers were looking for a safe place to land. Realizing that the only suitable landing area was to the right of the water-logged runway, Mitchell acquired a pair of signal flags and personally guided the carrier aircraft to earth in the role of a landing signal officer. The Marine general’s guidance resulted in no losses whereas, at Dulag, which was also waterlogged, eight of 40 carrier aircraft were damaged or destroyed in landings that were not so guided.

So, at the outset, the participation of Marine Air in the Philippines had an immense benefit—before even one Marine combat airplane arrived. Indeed, the scores of displaced U.S. Navy carrier aircraft played an important, if unplanned, role in supporting U.S. Army ground troops on Leyte––an earlier than expected turn of events owing in large part to the serendipitous contribution of a Marine aviator.

Arriving in the Philippines

On October 25, Army engineers began laying steel matting over Tacloban’s runway. They completed the job on October 27, and the first Army Air Forces fighters and fighter-bombers arrived the same day. (Medium and light bombers were withheld because the steel-matted runway was, at 2,500 feet, too short, and expansion was hampered with the advent of the rainy season.) By October 30, 182 USAAF P-38 and P-40 fighters had staged into Leyte and were well able to defend the new bases and provide support at sea and over the land. Two of the small captured airstrips at Burauen were abandoned because of drainage problems, but a new all-weather strip was started at Tanauan in November.

When the call from the Philippines came to Marine Air, it came at an unexpected time, for unexpected units to fulfill unexpected needs.

The big headache in the central Philippines was the growing threat posed by Japan’s first directed use of kamikaze aircraft, which were being vectored against Leyte’s seaborne lines of supply. An Army Air Forces P-61 Black Widow night fighter squadron was on the scene, but the two-place, twin-engine P-61s were unable to fly as fast as many of the one-way attackers. There were also U.S. Navy F6F night fighter detachments aboard several of the carriers, but it was felt that the carriers were pushing their luck by remaining tied to Leyte for so long a period as they were required to act as a mobile first line of defense. At the end of November, it was decided to swap a portion of Peleliu-based VMF(N)-541 (in F6F night fighters) for a portion of the outclassed Leyte-based P-61 squadron, and it was also decided to effect an immediate, unplanned transfer of four MAG-12 F4U squadrons to Leyte from the Solomons.

VMF(N)-541 was alerted for its move on November 28, and on December 1, MAG-12 was ordered to get VMF-115, VMF-211, VMF-218, and VMF-313 moving toward Tacloban by December 3. To support these thoroughly unplanned commitments, Marine R4Ds and Army C-47s based throughout the Pacific region were rallied to General Mitchell’s command to airlift Marine groundcrew personnel and aviation supplies to Leyte.

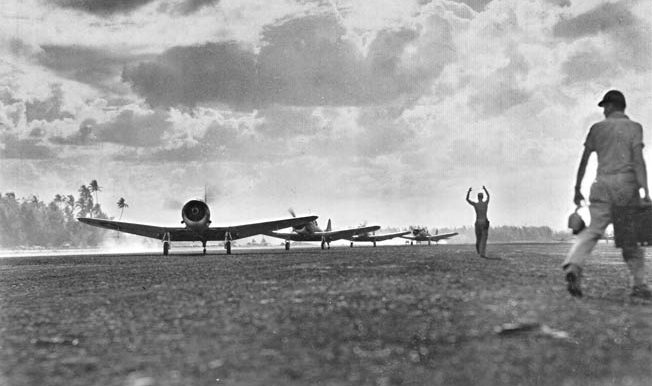

On December 2, a day early, MAG-61 PBJ medium bombers led 85 MAG-12 Corsairs from the Solomons to Leyte. The aircraft refueled at Hollandia, New Guinea, where three Corsairs dropped out with mechanical problems. The remaining 82 Marine fighters reached Tacloban on December 3, as did an F6F night fighter detachment from VMF(N)-541, following a 600-mile direct flight from Peleliu.

Marine Air had come to fight in the Philippines.

First Missions in the Philippines Campaign

VMF(N)-541 F6F night fighters logged their first missions of the Philippines campaign on December 3, the evening of the day they arrived at Tacloban. There was no contact with the enemy, but the night fighters provided cover for U.S. Navy PT-boats operating in the Surigao Strait. Flight operations were closed down by weather on December 4, but December 5 proved to be a red letter day in that VMF(N)-541’s 2nd Lt. Rodney Montgomery, Jr., became the second Marine F6F night-fighter pilot in history to down an enemy airplane—an Imperial Army Ki-43 Oscar fighter he downed at sea at 6:30 am. That evening, a VMF-115 F4U probably downed an Imperial Navy Zero fighter over Dulag. Two days later, two VMF(N)-541 pilots each downed a Japanese bomber, one at 1:45 am and the other at 6:10 am.

Marine F4U day fighters scored their first confirmed victories of the Philippines campaign three years to the day after Japanese aircraft opened the war in the islands with air attacks against American bases on Luzon. At 4:10 pm, VMF-313 F4U pilots downed two Oscars and probably downed another near Negros Island’s Alicante Airdrome. These were the squadron’s first aerial victories of the war.

Marine Aviators in a Support Role

In addition to air interdiction, the Marine day fighters began taking part in support operations. At first, despite heightened expectations, there were no close-support missions scheduled on behalf of the U.S. Army ground troops battling to pacify Leyte. Frankly, Army ground commanders were wary of close air support, and so an ongoing selling effort would have to be waged before there were assignments in that fundamentally untried arena. In the meantime, there were ample important assignments available for the four MAG-12 Corsair squadrons.

On the morning of December 7, in conjunction with Army Air Forces attacks on the same targets, 12 VMF-211 F4Us were dispatched against seven Japanese troop- and supply-laden vessels making for Leyte’s Ormoc Bay. When the Marines arrived, they found the ships at anchor, well covered by a powerful Japanese fighter umbrella. Eight F4Us engaged the top cover while four bomb-laden F4Us went after the ships. Three F4Us were downed in the action, but credit was given for a bomb hit on an Imperial Navy destroyer.

During the afternoon—while American transport ships arrived in another part of Ormoc Bay to land a U.S. Army infantry division—Marine F4Us joined Army Air Forces P-38s in repeatedly attacking the Japanese ships. Bomb-equipped F4Us from three squadrons, escorted by Army Air Forces fighters, were credited with sinking a troop transport, three of the cargo ships, and a destroyer. In return, Japanese aircraft, including kamikazes, attacked the U.S. convoy through heavy cover provided by P-38s. The Japanese severely damaged a transport and a destroyer, both of which had to be abandoned and scuttled by friendly fire, and a landing ship that also had to be abandoned. On the other hand, the American landing was a success, and the Japanese reinforcement and resupply effort was not.

On December 10, at 4:40 pm, two VMF-115 F4U pilots teamed up to destroy a Japanese reconnaissance plane near Leyte. Another Japanese reinforcement and resupply convoy made a dash toward Leyte on December 11 and was discovered early. Among other attack groups, 27 Marine F4Us from all four MAG-12 squadrons attacked the ships 40 miles from Panay Island with 1,000-pound delay-fuse bombs. The VMF-313 pilots attacked a large troop transport and scored two direct hits, and VMF-115 pilots set a cargo ship afire with at least one direct hit.

VMF-211 pilots scored no hits, and VMF-218 pilots were unable to observe the results of their attack because they were bounced by seven Imperial Navy Zeros as they came off their target. In the ensuing melee, the Marines claimed six enemy fighters downed, but no official credits were ever issued.

Thirty bomb-laden Marine F4Us escorted by P-40 fighters attacked the same convoy at sea during the afternoon of December 11. Attacking from masthead height, VMF-313 was credited with sinking a large troop transport, a destroyer, and a cargo ship, and with damaging two freighters. Two F4Us were downed by antiaircraft fire, and two others were severely damaged. VMF-115 pilots hit two cargo ships, but two Corsairs were knocked down in the attack; VMF-218 pilots claimed hits on a cargo ship and left a destroyer burning while losing one of their number to antiaircraft fire.

Throughout the day, as many of their comrades attacked the Japanese convoy, other MAG-12 F4Us flew defensive air patrols over U.S. Navy ships bent on similar missions, also in Ormoc Bay. A VMF-218 pilot downed an Imperial Navy D3A Val dive-bomber over Ormoc Bay at 7:45 am; pilots from three squadrons downed nine Japanese fighters at sea west of Leyte between 11:00 and 11:30 am; and Marine F4U pilots from all four squadrons downed nine Japanese fighters over Ormoc Bay and to the west between 3:30 and 5:16 pm. In all, victory credits were awarded for 18 fighters and one dive-bomber––the best one-day total by Marine fighters since January 23, 1944, when 45 Japanese aircraft were downed by Marines over Rabaul.

On the morning of December 12, VMF(N)-541 F6F night fighters were vectored to the west coast of Leyte to intercept an incoming air strike. At 7:20 am, the night pilots found 33 Japanese bombers and fighter escorts heading toward the U.S. Navy ships in Ormoc Bay, and they broke up the attack and downed 11 of them—without loss.

Three days later, Marine F6F night-fighter pilots downed an Imperial Navy fighter and three Imperial Navy dive-bombers near Negros Island at 8:40 am. And while covering the U.S. Sixth Army’s invasion of Mindoro Island, VMF-211 F4U pilots downed five Imperial Navy Zero fighters at 9:00.

Thereafter, Japanese air attacks pretty much petered out. Marine fighters were credited with downing nine enemy aircraft, mostly in areas north of Leyte, but the bulk of their late December missions were undertaken in a point-defense role.

Though hardly the sort of duty the Marine day fighter pilots expected to be engaged in following their freewheeling offensive experience in the Solomons, the protection of friendly airfields and convoys and attacks upon enemy shipping were certainly missions they were qualified to undertake, and their success was a shining example of their do-all versatility.

264 Combat Missions in the Month of December

December 1944 was also noteworthy for Marine Air in that their first ground-attack missions in the Philippines were clocked during the month. The first of these was mounted by Marine F4Us on December 10, against Japanese troop bivouacs. These were hardly the precision, on-call, ground-guided close-support missions for which Marine dive-bomber pilots were training to undertake in the Philippines, but to the extent that results could be observed, the F4U pilots left fires raging at all the sites attacked.

Flights composed of 12 bomb-laden F4Us struck ground targets again on December 17 and 19, and then the MAG-12 ground-attack missions through the rest of the month were devoted to interdicting Japanese airfields on Mindanao and Luzon, the main islands to the south and north of Leyte, respectively. Also, during the latter part of the month, in missions assigned by U.S. Fifth Air Force planners, Marine Corsairs began to be employed interchangeably with two Army Air Forces fighter groups in attacks on trains, rail lines, bridges, and crossroads towns on Luzon, which was scheduled to be invaded on January 9, 1945.

In all of December 1944, Marine day fighters based at Tacloban (and, after December 27, at the new all-weather air base at Tanauan) flew 264 combat missions. They were credited with the destruction of 22 vessels ranging in size from small coastal craft to warships and ocean-going transports and freighters. And official credit was awarded to Marine day-fighter pilots for the downing of 31 Japanese aircraft. VMF(N)-541 flew 312 sorties out of Tacloban in December 1944, and its pilots were officially credited with downing 20 enemy planes, both at night and during the day. VMF(N)-541 returned to Peleliu on January 11, having downed two additional Japanese aircraft.

Although its introduction into the new Philippines theater was both early and unexpected, Marine Air performed a wide variety of missions extremely well. Serving in unique aircraft types under the command of the U.S. Fifth Air Force, Marines with inter-service experience in the Solomons dating back to 1942 smoothly integrated themselves and their capabilities into the theater air big picture and functioned admirably as part of the team.

Certainly, they added the punch and power Army-based Philippines command needed and welcomed. But the year ended for the Marines without their having been called upon even once to demonstrate their new forte: close air support of ground troops in combat. That would come on an island to the north of Leyte, in the new year. (Read the Second Installment)

Tacloban airstrip was actually on the northeast coast of Leyte, not the west coast.

thank you. My dad was a vmf 211 pilot 1943-1944, I want to find photos and any info on his time there. Hope you can guide me.

I also want to find info and photos of VMF 211 Zamboanga 1945. I am fascinated by my collection of photos from 13 th AF P-38;s and specifically VMF 211 as these were taken from that group by their Marine Corps photographer. These photos show the KI 43 Oscar Tail sign, some high ranking officers. The name Acre, and possibly Meyer may be some of the names of USMC personnel. 13th AF p-38 showing name Capt. Sommerich’s “Saint Luis Blues II”, yes II not the same as his first Saint Loise Blues seen on Website.

My father, 1st Lt Cecil Wilson, was a Corsair pilot with VMF-218 and was credited with gunning down a Japanese “Zeke” (aka Zero) on his birthday 12/11/1944.