By Colonel Dick Camp (ret.)

Prologue: At the start of World War II, Midway Atoll was a key U.S. base in the central Pacific. Only 1,200 miles from the Hawaiian Islands, it was the outer shield for the strategically important naval base at Pearl Harbor. In early May 1942, U.S. Navy codebreakers learned that the Japanese intended to invade Midway with a powerful armada under the command of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, mastermind of the Pearl Harbor attack.

Midway’s airborne defenders, Marine Air Group 22 (MAG-22)—Marine Scout-Bombing Squadron 241 (VMSB 241) and Marine Fighting Squadron 221 (VMF 221)—hurriedly reinforced the atoll’s defenses. MAG 22’s Action Report noted that on May 26, “USS Kitty Hawk arrived with 22 officers and 35 men … also 19 SBD-2 and 7 F4F-3 aircraft. Of the 21 new pilots, 17 were fresh out of flight school.”

“Many Bogies Heading Midway”

MAG-22 was based on Eastern Island, two miles west of Sand Island, the site of the Naval Air Station and headquarters of the Sixth Marine Defense Battalion, the atoll’s ground defense unit. On June 3, 1942, a PBY5A Catalina flying boat from VP-44 was on the outboard leg of its search pattern when the pilot, Ensign Jack Reid, spotted specks on the horizon. “I think we hit the jackpot,” he exclaimed.

[text_ad]

He immediately radioed Pearl Harbor: “Sighted main body,” followed by, “Bearing 262, distance 700 miles.” Midway went to full alert.

Early the next morning, the radio station at Sand Island sent out the message: “Many bogies heading Midway, bearing 320 degrees, distance 150 miles, angels 11.” The heart-pounding wail of the island’s air raid siren sent the Marine pilots scrambling to man their aircraft—no one wanted to be caught on the ground in a bombing raid. Second Lt. J.C. Musselman, VMF-221 duty officer, jumped in the squadron truck and raced along the line of aircraft revetments gesturing wildly. “Get airborne,” he yelled. Within minutes, the taxiway was crowded with an assortment of aircraft urgently scrambling to get into the air. Major Floyd B. Parks led off with a five-plane division of Brewster F2A-3 Buffalo fighters.

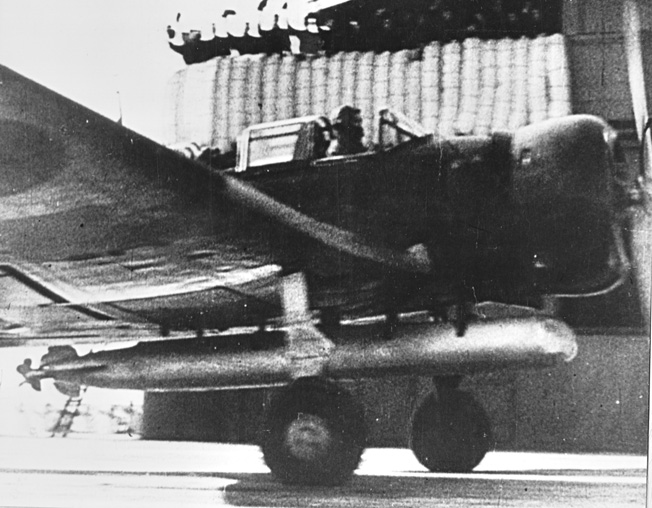

Parks was closely followed by three other F2A-3 divisions and one three-plane division of Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighters led by Captain John F. Carey. Altogether, VMF-221 put 26 aircraft into the air. One aircraft flown by 2nd Lt. Charles S. Hughes developed engine trouble and turned back. Major Lofton R. Henderson’s VMSB-241 Douglas SBD-2 Dauntless and Vought SB2U-3 Vindicator dive bombers joined the stampede. Within minutes MAG-22’s two squadrons were airborne, leaving an empty field and a strange quietness after the frenzied roar of departing aircraft.

Diving on the Enemy Formation

Once aloft, Captain Carey peered intently through the windshield of his Wildcat fighter. Scattered white cumulous clouds cut visibility, making it difficult to see the reported “many bogies heading Midway.” Carey’s three-plane division was at 14,000 feet searching for inbound Japanese raiders; 2nd Lt. C.M. Canfield was echeloned right and slightly to the rear, while Captain Marion E. Carl was several hundred yards behind. Canfield slid behind his leader as Carey “made a wide 270 degree turn, then a 90 degree diving turn.” Canfield’s radio suddenly came alive with Carey’s electrifying, “Tallyho! Hawks at angels 12”… a slight pause … “accompanied by fighters.”

Two thousand feet below, 72 Japanese Nakajima B5N2 Kate torpedo planes and Aichi D3A1 Val dive bombers arrayed in five “V” formations roared toward Midway. An escort of 36 Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighters flew just above and behind them. The Zeros were out of position, allowing the Americans one free pass on the rest of the flight.

Carey started his run “high side from the right” on the leader of the first “V.” He waited until the enemy plane filled his gun sight and then mashed the firing button. Four .50-caliber machine guns shredded the bomber, setting it on fire, but not before its gunner put a round through Carey’s windshield. Milliseconds later, the Kate blew up, filling the air with debris.

Canfield followed Carey through the enemy formation and “fired at the number three plane in the number three section until it exploded and went down in flames.” In the middle of the run, the thoroughly aroused Zero escort dove on the three Americans, cannons and machine guns blazing. Carl “made a high side pass on one of the fighters some 2,000 feet below. My fire passed through my target and I pulled away and up. I was surprised to see several Zeros already swinging into position on my tail.” The fight was on.

“AF”

By the summer of 1942, the Japanese juggernaut appeared to be unstoppable. After the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, American bases at Guam, Bataan, Corregidor, and Wake Island fell, sending thousands of American servicemen into captivity. Many in the United States thought that Hawaii would be next, a belief strengthened by the ineffectual bombing of Oahu by a single Japanese seaplane on the night of March 4, 1942.

About this time, U.S. Navy cryptologists at Station Hypo in Hawaii had achieved some success in breaking the Japanese fleet code, JN-25B. However, the code was so complicated that only partial decrypts—every six or seven words, 10 to 15 percent—were produced, leaving the analysts with a difficult puzzle to solve. Several of these partially decrypted messages indicated that a major Japanese operation was going to be conducted against “AF” in late May or early June 1942.

The attack was to be led by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack, and was to comprise four of the six aircraft carriers—Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu, and Soryu—that devastated the American battle line at Pearl Harbor on December 7.

Navy codebreakers argued over whether “AF” stood for Midway, an island located approximately 1,200 miles northwest of Oahu, or some other location, including Hawaii or even the U.S. West Coast. A ruse was developed to resolve the argument; Midway was advised to broadcast in the clear that the island was experiencing a water shortage. Within days, a Japanese message was intercepted advising of a “water shortage at AF,” and thus ending the controversy. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief U.S. Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC), rushed reinforcements to Midway.

Brewster Buffalo vs Mitsubishi Zero

Major Parks led his division’s obsolete Buffalos against the Japanese dive bombers and was immediately jumped by the faster, more agile Zeros. One pilot described the uneven dogfight: “[It] looked like they were tied to a string while the Zeros made passes at them.”

Parks, one of the first victims, bailed out of his burning aircraft. His parachute opened and, as he dangled from the shroud lines, one of the Japanese strafed the helpless pilot all the way down—and continued to fire even as the body landed on a reef. Parks may have had a premonition the night before his death. Normally an extrovert, he was moody and distracted. Captain Kirk Armistead tried to cheer him up. “By this time tomorrow it’ll all be over.”

“Yeah,” Parks replied, “for those of you who get through it.” All the pilots in Parks’s division were shot down.

Armistead’s seven-plane division (six F2A-3s and one F4F) attacked in column, starting their firing run at 17,000 feet. His target consisted of “five divisions of from 5 to 9 planes each, flying in division ‘Vs.’” He made a high speed, head-on approach. “I saw my incendiary bullets travel from a point in front of the leader, up through his plane and back through the planes on the left wing of the V.” Armistead looked back as he continued his dive and saw three Japanese planes falling in flames.

Captain William C. Humberd rolled in behind Armistead. He shot down one bomber in a high-side approach and attacked again from the other side. “I was halfway through another run when I heard a loud noise and, turning around, saw a large hole in the hood of my plane … and two Jap Zeros on me about 200 yards astern.”

Humberd pushed over in a steep dive to escape, but an enemy plane was glued to his tail. “I stayed at water level with full throttle,” he reported, “until I gained enough distance to turn into him. We met head on. I gave him a long burst at 300 yards and he went down on fire.”

Armistead pulled out of his dive and zoomed back to 14,000 feet for another run. “I looked back over my shoulder and about 2,000 feet below and behind me I saw three fighters in column, climbing toward me, which I assumed to be planes of my division. When the nearest plane was about 500 feet below and behind me, I realized that it was a Japanese Zero fighter. I kicked over in a violent split ‘S’ and received three 20mm shells, one in the right wing gun, one in the right wing tank, and one in the top left side of the engine cowling. I also received about 20 7.7mm rounds in the left aileron … which sawed off a portion of the aileron.”

He went into a power dive, barely in control as his aircraft corkscrewed toward the ocean. The Japanese fighters pulled off, assuming that the American was done for. However, Armistead gained control, pulling out at 500 feet before shakily landing on Eastern Island. Humberd landed shortly afterward with his battle-damaged aircraft. “My hydraulic fluid was gone, and my flaps and landing gear would not lower, so I used my emergency system to lower my wheels.” He landed safely, although his plane had a number of holes––three or four in the left gasoline tanks and two 20mm holes in the fuselage.

Second Lieutenant William B. Sandoval was not so fortunate. One of his wingmates thought that he was drawn flat on his firing run and got “nailed” by a rear gunner. He failed to return and was listed as killed in action along with 2nd Lts. Martin E. Mahannah and Walter W. Swansberger.

Lone Survivor in the Second Division

Captain Philip R. White was the only pilot in the second division to survive. “After the first pass, I lost my wing man and the rest of the division,” he reported; Captains Daniel J. Hennessey and Herbert T. Merrill, and 2nd Lts. Ellwood Q. Lindsay, Thomas W. Benson, and John D. Lucas were all shot down.

After a series of violent maneuvers, White was able to outmaneuver the enemy’s Zeros while shooting down one and possibly two Val dive bombers. In an after-action report, he stated, “The F2A-3 is not a combat aircraft. It is inferior to the planes we were fighting in every respect.”

As the aerial battle continued, Captain Carey pulled out of his dive and started to make a high wing over attack when his Wildcat was raked by a burst of fire that tore through his right knee and left leg. In excruciating pain and in danger of losing consciousness, he “dove at about a 40 degree angle and headed for a large cloud about five miles away.”

At the same time Canfield’s Wildcat was “hit on the right elevator, left wing and flap and just ahead of the tail wheel by a 20mm cannon shell. There was also a .30-caliber hole through the tail wheel and one that entered the hood on the right side about six inches up, passing just over the left rudder pedal and damaging the landing gear.” He wisely followed Carey to safety.

“I went around the cloud in the opposite direction,” he reported, “and joined up with him again. Carey headed in the general direction of the island on an unsteady course and kept dropping and falling behind. I kept throttling back so he could keep up. His wounds kept him from working the rudders and his plane was ‘all over the sky.’”

The two pilots reached the field, which was under attack, and prepared to land. Canfield discovered that he did not have any flaps to slow him down. “When the wheels touched the ground, the landing gear collapsed and the plane slid along the runway. When it stopped, I jumped out and ran for a trench just as a Japanese plane strafed my abandoned plane.”

Marion Carl was also lucky. He “headed straight down at full throttle” and managed to shake his pursuers. He pulled out of the dive, climbed to 20,000 feet, leveled off, and looked for another target. Below him, three Zeros were circling, intent on finding another victim. They didn’t see Carl “drop astern and to the inside of the circle made by one of the fighters. I gave him a long burst, until he fell off on one wing … out of control, headed straight down with smoke streaming from the plane.”

Despite being shot up, Carl was able to limp back to safety. Carl went on to become the Marine Corps’ seventh-ranking fighter ace with 181/2 victories. He retired in 1973 as a major general with 14,000 flight hours.

Heavy Casualties For VMF-221

The squadron had been all but wiped out as a fighting unit. Of the 25 aircraft from VMF-221 that rose to challenge the Japanese, 15 were shot down and only two of the remainder were flyable after the brief but deadly encounter. The Air Group listed 15 pilots missing in action, later changed to killed in action, and four wounded in action. Carl wrote, “Most of the surviving pilots were stunned by their experience … the CO and exec both were missing; nobody seemed to know if any of the others might have bailed out … VMF-221 was a shattered command.”

The surviving pilots could take some solace in downing six confirmed Japanese planes and damaging 34 others, thus saving the island from an even heavier bombing. One observer noted that the first and second wave of Japanese dive bombers left the carriers with 72 planes; only 38 reached the island. But there was more drama to come.

“Here They Come!”

Radio-Gunner Corporal Eugene T. Card of Marine Scout-Bombing Squadron 241 (VMBS-241) anxiously gripped the stick of his Douglas SBD-2 Dauntless dive bomber, trying to keep it straight and level, while his pilot, Captain Richard E. Fleming, feverishly worked out the location of the Japanese aircraft carriers on his chart board. The order they had been given—“Attack enemy carriers bearing 325 degrees, distance 180 miles, on course 130 degrees at a speed of 25 knots”—seemed simple enough, but trying to locate the Japanese ships in the huge expanse of ocean was akin to finding the proverbial needle in a haystack.

Suddenly, Card noticed 1st Lt. Daniel Iverson’s SBD-2 closing up fast. As he came alongside, Iverson and his gunner, Corporal Wallace J. Reid, gestured frantically downward to the left. Card craned his neck, but all he could see was blue sea through the scattered cloud cover. His attention was diverted by Fleming’s voice over the intercom, “We’ve made contact. There’s a ship at 10 o’clock, do you see it?”

Card looked again and there it was––a slender, black shape trailing a long white wake as the ship sped toward Midway. Fleming retook control of the aircraft while Card secured his control stick and manned the single .30-caliber machine gun in the rear cockpit. Within minutes, more and more Japanese ships could be seen, including the unmistakable shapes of two aircraft carriers.

Card watched utterly fascinated as the carriers turned into the wind and started launching aircraft. His reverie was abruptly broken by the squadron commander’s voice: “Attack two enemy carriers on port bow.” The SBD-2 fell away, losing altitude for a low-level glide-bombing attack. All at once, two streaks of smoke flew past the starboard wing and Fleming’s excited voice called out, “Here they come!”

A Japanese Zero flashed by, climbing almost straight up. Card turned his .30-caliber machine gun on the fighter but it was already out of range. Another slashed through the formation. Out of the corner of his eye, Card saw a burning aircraft plummeting toward the ocean; a white parachute blossomed, but he could not make out whose it was. His SBD continued to bore in toward the target amid a tangle of diving aircraft.

Henderson’s Plan of Attack

Major Lofton R. Henderson, CO of VMSB-241, cringed at the thought of taking his inexperienced pilots—“the ‘greenest’ group ever assembled for combat—into battle. Ten of 28 pilots had joined the squadron in the last week and only three had any time in SBDs. However, there was nothing else to be done. Yamamoto’s immense naval task force was approaching Midway. Lt. Col. Ira L. Kimes, CO of MAG-22, remarked, “It [Japanese task force] appears to have everything but Hirohito with an outboard motor on his bathtub.”

An accidental explosion in the fuel dump caused a shortage of gasoline (300,000 gallons were lost), which limited pilot training to “two or three hops with practice bombs,” and left Henderson with little choice but to devise an attack plan that would give his untrained pilots the best chance for success. He divided them into two striking units—one led by himself (18 SBD-2s with the more-experienced pilots) and the other led by Major Benjamin W. Norris with 12 of the older SB2U-3s; the SBD-2’s performance was far superior to that of the other aircraft.

Henderson planned on a shallow glide-bombing approach because it required less skill than a diving attack. In a series of briefings and chalk talks, he instructed the pilots that he would lead them in a fast power glide to 4,000 feet and then turn them loose to hit the carriers at a very low altitude—500 feet or less. He cautioned the youngsters to get out fast by hugging the water and using the cloud cover to escape. Everyone knew their SBDs were sadly outclassed by the Japanese Zero, but there was nothing to be done about it.

Lastly, Henderson instructed them that, upon notice of an incoming raid, they were to get off the ground as quickly as possible and assemble at Point Affirm—20 miles east of Midway.

Corporal Card heard a “Wuf!”… and another and another. Black puffballs appeared near his plane, and he realized the sound was from Japanese antiaircraft fire. He was too busy fighting off the Zeros to pay much more attention until “somebody threw a bucket of bolts in the prop,” and small holes appeared all over the cockpit. He told Walter Lord, the well-known author, that he “felt a thousand needles prick his right ankle … and something hard kick his left leg to one side.” Blood streamed down his legs but he had no time to stop the bleeding, as the Zeros kept boring in and he had to keep them at bay.

Henderson was ahead of Card’s plane, leading the attack, and Dan Iverson was just behind. “The first [enemy fighter] attacks were directed at the squadron leader in an attempt to put him out of action,” Iverson recalled. “After about two passes, one of the enemy put several shots through his plane and the left wing started to burn … it was apparent that he was hit and out of action.”

Henderson’s wingman, 2nd Lt. Albert W. Tweedy, followed him faithfully until he, too, was shot down. Captain Armond H. DeLalio, leader of the third section, watched horrified as 2nd Lt. Thomas J. Gratzek’s plane burst into flames and plunged toward the sea. Three other SBDs quickly followed—2nd Lts. Maurice A. Ward, Bruno P. Hagedorn, and Bruce H. Ek, along with their radio-gunners, Pfcs. Harry M. Radford, Joseph T. Piraneo, and Raymond R. Brown.

Striking the Enemy Carriers

The survivors, led by Captain Elmer G. “Iron Man” Glidden, pressed the attack through a protecting layer of clouds. “On emerging from the cloudbank, the enemy carrier was directly below,” Glidden recalled, “and all planes made their runs.” They were assailed on all sides by fighter planes and heavy antiaircraft fire, but the radio-gunners fought back valiantly.

Card had the satisfaction of seeing a Zero burst into flames. Pfc. Reed T. Ramsey got a hit at point-blank range, however, Private Charles W. Huber’s gun jammed; all he could do was point it, hoping to fool the pursuing Japanese. In the heat of battle, Pfc. Gordon R. McFeely got so carried away that he riddled the tail of his own aircraft.

Glidden picked out a carrier that had “a huge Rising Sun amidships of the flight deck … [which] itself was a gleaming light yellow, making it a tempting target.” The rest of the squadron followed, dropping three 500-pound bombs that neatly bracketed the warship. “Looking back,” Glidden reported, “I saw two hits and one miss that were right alongside the bow. The carrier was starting to smoke.”

Dan Iverson bored in on another ship, “a carrier that had two Rising Suns on the flight deck … two enemy fighters followed me in the dive. I released my bomb at 300 feet before pulling out. It hit just astern of the deck, a very close miss … [but] may have damaged the screws and steering gear.”

The SBDs Run Back to Base

Having expended their ordnance, the SBDs beat a hasty retreat. “The fighters pursued us,” Iverson related, “making overhead runs for 20 or 30 miles. My plane was hit several times.” This was an understatement, as over 250 holes were counted in his aircraft. His throat mike was severed by a bullet, the hydraulic system was shot away, and only one landing gear would lock down.

Second Lieutenant Richard L. Blain and his crewman, McFeely, found themselves in the water. “The ship stayed afloat for two or three minutes,” Blain reported, giving them a chance to get in their life raft. After two days on the ocean, they were picked up by a passing patrol plane. Second Lt. Harold G. Schlendering and Pfc. Edward O. Smith had to hit the silk. The pilot survived but the gunner did not.

As the battered remnants of Henderson’s division cleared the scene, Norris’s slow and clumsy Vindicators arrived. “The clouds became our haven,” remembered 2nd Lt. Allen H. Ringblom. “Major Norris led us without loss to the target … radioing instructions to dive straight ahead on the target.”

Second Lieutenant George T. Lumpkin observed, “Major Norris started his dive immediately from 13,500 feet through the cloud cover … and came out on the port side of a large battleship.” Lumpkin followed, running a gauntlet of fire that was so heavy it was “practically impossible to hold the ship in a true dive.” During his dive, Ringblom “received identical holes, about 6 inches in diameter, in each aileron.” The Japanese battleship zigzagged frantically, trying to throw off their aim.

The Marines released their bombs and “saw the battleship practically ringed with near misses, also one direct hit on the bow,” according to 2nd Lt. George E. Koutelas. Second Lt. Sumner H. Whitten came out of his dive and found himself between two lines of enemy ships that were firing furiously trying to knock him down.

“Eight Out of 16″

Sergeant Frank E. Zelnis, Whitten’s gunner, thought it was taking forever to get away and he called out impatiently, “You dropped your bomb; let’s get the hell out of here before we get hit!” Whitten recalled, “I made a sharp right turn and started home at 100 feet.”

As they pulled out of their dives and attempted to escape, the Zeros swooped down. Second Lt. Daniel L. Cummings lost his gunner, Private Henry I. Sparks, almost immediately. He related that Sparks “had never before fired a machine gun in the air and could not be expected to be an effective shot much less protect himself.”

Cummings counted five enemy planes on his tail. “In the hit and run, and dog fighting, which was my initiation to real war, my old, obsolete SB2U-3 was almost shot out from under me. About five miles from Midway, my gasoline gave out and I made a crash landing in the water.”

Ringblom had “a Zero pass right behind me as I whipped into a tight turn, only luck making harmless the numerous passes made by the Zeros.” Like Cummings, Ringblom also ditched. “I chose to land right in front of a PT boat and all went so well that I even forgot to inflate my life jacket.”

After many perilous encounters, the rest of the squadron made it back to the island. Ringblom arrived dripping wet. A buddy greeted him, saying, “Well, I never expected to see you again.” A very much relieved Ringblom blurted out, “Hell, neither did I!”

Fleming executed a perfect three-point landing despite a shot-out tire. As Marines rushed up to take Card away, Fleming announced, “Boys, there is one ride I am glad is over,” and shook his wounded gunner’s hand.

Second Lieutenant Thomas F. Moore remembered calling to his buddy, 2nd Lt. Jesse D. Rollow, Jr., “How many got back?”

“Eight out of 16,” Rollow replied, shaking his head sadly.

“Their Sacrifice Was Not in Vain”

Of the 16 SBD-2s and 11 SB2U-3s that scrambled aloft to attack the Japanese fleet on that fateful June morning, 12 were shot down (eight SBDs and four SB2Us), seven severely damaged beyond repair, and four slightly damaged. The Marine claims of the number of enemy aircraft destroyed and ships hit proved to be wrong. Subsequent research of Japanese records showed that little actual damage was done—no enemy ships were struck by VMSB-241’s bombs and only six aircraft failed to return to the carriers. Many can argue that the sacrifice of so many Marine pilots and crewmen was in vain. However, Admiral Nimitz was not one of them.

“Please accept my sympathy for the losses sustained by your gallant aviation personnel based at Midway,” he wrote. “Their sacrifice was not in vain. When the great emergency came, they were ready. They met unflinchingly the attack of vastly superior numbers and made the attack ineffective. They struck the first blow at the enemy carriers. They were the spearhead of our great victory. They have written a new and shining page in the annals of the Marine Corps.”

Join The Conversation

Comments