By John Perry

When Nazi architect Albert Speer surrendered in 1945, he made a strange remark: “So now the end has come. That’s good. It was all only a kind of opera anyway.”

Minister for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda Josef Goebbels agreed that Hitler turned politics into a grand play. Even the Führer called himself “the greatest actor in Europe,” enjoying contact with movie stars while plunging the world into a melodrama of madness. Through years of political propaganda, theatrical trappings, and charismatic speaking, this vagrant beer hall agitator became what biographer Alan Bullock called “the greatest demagogue in history.” During his rise to power, Hiter warned that the German people “must not be allowed to find out who I am. They must not know where I came from and who my family is.”

The blurred youth of Adolf Hitler set the stage for his meteoric rise to power after World War I. His harsh Austrian father Alois (Schicklgruber was the original family name) earned a middle-class income as chief customs official in Linz, the Austrian town Hitler later wanted to make the Reich’s cultural capital. Clara, his indulgent mother who died of cancer, called her thin, pale-faced, irascible boy “moonstruck” because he lived in a dream world.

Childhood friend August Kubizek later wrote that Adolf showed “a gift for oratory from his earliest youth. And he knew it. He liked to talk, and talked without pause. Sometimes when he soared too high in his fantasies I could not help suspecting that all this was nothing but an exercise in oratory.”

A teacher in Linz also remembered “Hitler holding duologues with trees stirring in the wind.” And in his book Mein Kampf jailbird Hitler reminisced that his “oratorical talent was being developed in the form of more or less violent arguments with my schoolmates.”

Hitler drifted to Vienna, selling watercolors and painted postcards on the street after twice failing the entrance exam to the Academy of Fine Arts—a slight that, coupled with his mother’s death, left unhealed scar tissue. Interestlingy, evidence of anti-Semitic hatred in Hitler seems slim before the end of World War I. Even then the social misfit with “lightning in his eyes” would jump to his feet and rave about Socialists, “not avoiding vulgarisms, in a very impetuous way” while dabbing paint on canvas and waving a T-square in the air. The budding artist sometimes sketched soap advertising posters, one showing black boots with a red background and white letters, colors later part of the Nazi flag. Hitler called these difficult days his “granite foundation.”

Vienna planted the seeds for Hitler’s perverse political platform through access to cheap printed material. He skimmed books, newspapers, pamphlets, the magazine Ostara, and the illustrated monthly Der Scherer, generally publications that supported his deluded ideas. Two arcane German writers, Guido von List and Jorg Lanz von Libenfels, helped feed fantasies of a glorious Germanic past full of pageantry and pagan rituals. It is also likely that he read Protocols of the Wise Men of Zion and Houston Stewart Chamberlain’s The Foundations of the Twentieth Century. Hitler also liked the romantic Western cowboy and Indian novels of Karl May.

It is probable that Hitler stayed in Vienna to avoid the draft. He returned to Munich when conditions seemed safe, but the Army summoned him for an examination. Military doctors found the future Army commander “not strong enough for combatant and non-combatant duties,” and rejected him as “unfit for military service.” Nevertheless, he managed to join the Bavarian Army and served as a regimental dispatch runner. Before the end of World War I, Hitler was gassed and injured. He recovered in a hospital where the psychiatric department labeled him a psychopath with hysterical symptoms. He did receive the Iron Cross twice but never rose above corporal (actually a private) because superiors felt this oddball lacked leadership qualities.

“He Has a Big Mouth. We Could Use Him.”

Germany became an economic wasteland after World War I. Out of this rubble rose magicians and messiahs, but the National Workers Party hit the jackpot with Hitler, lashing at communists, capitalists, intellectuals, trusts and monopolies, the French, the Polish and Jews, anything to create mass frenzy through fear.

After the war, Hitler returned to Munich and became involved in the Bavarian Soviet Republic. Film footage shows him marching at a funeral, head high, with an armband the color of the Socialist revolution. He remained in the army and did guard duty at a POW camp and train station. The Information Department offered “speaker courses” as training tools for troops. An instructor recalled, “The men seemed spellbound by one of their number who was haranguing them with mounting passion in a strangely guttural voice. I had the peculiar feeling that their excitement derived from him and at the same time they, in turn, were inspiring him.”

Officer Karl Mayr heard about Hitler’s oratorical skills and enlisted him as an undercover agent. “He was like a tired stray dog looking for a master” and “ready to throw in his lot with anyone who should show him kindness.”

Mayr later wrote: “He was totally unconcerned about the German people and their destinies.” The beer hall stumper spoke on topics such as “Social and Economic-Political Slogans.” Some soldiers found his talks “spirited,” one calling him “a born popular speaker.” Hitler exclaimed in Mein Kampf, “I could speak.”

He soon realized this talent paved the road to profit. August Kubizek read about his oratory in the 20s and recalled, “I was very sorry that he had no more been able to follow through with his artistic career than I had.… Now he had to make a living as a speaker at assemblies. Tough job.”

Mayr also used Hitler as a stooge to attend meetings of radical political parties in Munich. One group was called the DAP (German Workers Party, later changed to National Socialist German Workers Party, shortened to Nazi). Instead of observing, he shouted down a guest speaker and gained attention, leading the party’s founder to remark, “He has a big mouth. We could use him.”

Inspiration in Erik Jan Hanussen

Hitler joined the splinter group in 1919 and soon handled party propaganda, seeing himself as a drummer for the great revolution yet rapidly becoming the outspoken party voice. In 1920, for example, he roused crowds at over 30 mass meetings. The next year he spoke to over 6,000 members at Munich’s largest hall, and in 1922 an audience of 50,000 at a Nazi rally in Munich. Hitler may have been obscure in most of Germany, but not among diehard Nazis whose number soon reached 55,000. As businessman Kurt G.W. Ludecke recalled, “His words were like a scourge. When he spoke of the disgrace of Germany, I felt ready to spring on any enemy.”

During this incubating period, Hitler designed symbols for the Nazi party, most derived from earlier sources. A crooked cross called the swastika, black in a white circle with a blood-red field used as part of the esoteric Thule Society’s emblem, appeared for the first time in 1920.

Hypnotist, clairvoyant, and stage magician Erik Jan Hanussen is often overlooked as an influence on Hitler’s speaking style. Former Nazi ranking member Otto Strasser told a psychoanalyst in 1942, “Hitler took regular lessons in speaking and in mass psychology from a man named Hanussen, who was also a practicing astrologer and fortune-teller. He was an extremely clever individual who taught Hitler a great deal concerning the importance of staging meetings to obtain the greatest dramatic effect.” The Führer learned crowd control through gestures and the use of garish poses from Hanussen, who was later murdered by Nazis.

Pretty soon the unemployed young orator rode around in a Mercedes convertible carrying a rhinoceros whip and wearing a hat and long raincoat. Admirers called this carnival sideshow barker Germany’s young messiah and Germany’s Mussolini. Yet he still insisted, “I am nothing but a drummer and a rallier.” That soon changed.

The Publicized Putsch in Munich

Many saviors preached to Germans after World War I to gain political power. Papers often reported street fights, plots, and putsches to overthrow the government. On November 8, 1923, several thousand people packed a large Munich beer hall to hear the prime minister of Bavaria speak. Suddenly, the doors flew open and Hitler, flanked by storm troopers, entered with a holstered Browning revolver. He leaped on a beer table, fired a shot into the ceiling, and took politicians hostage. A heated oration ensued. The shaking, sweating Hitler screamed, causing beer drinkers to applaud. One spectator thought the hoarse, unshaven future Führer looked like “a poor little waiter.”

Snow and rain began to fall outside. Traffic stopped. Thugs with guns and clubs patrolled side streets. Yet, Hitler failed to take over government buildings, the railway station, and phone exchanges. Former World War I general Erich Ludendorff made the mistake of letting hostages go free on their honor. The ill-conceived putsch petered out by morning when Ludendorff decided to organize a protest march downtown. Hitler bought the idea. Gunfire broke out with state police. When the smoke cleared, over a dozen Nazis had been killed or wounded. Hitler fled in a yellow Opel and hid in a rich supporter’s attic, threatening to commit suicide.

The publicized Munich trial of conspirators turned into a travesty as Hitler dominated the courtroom, speaking for hours in a trance about the Versailles Treaty and the betrayal of the Fatherland. “You may pronounce us guilty a thousand times over, but the goddess of the eternal court of history will smile and tear to tatters the brief of the State Prosecutor and the sentence of this court. For she acquits us.”

When Hitler received a short prison sentence instead of being deported, crowds cheered both inside and outside the courtroom. Newspaper reporters featured the dramatic beer hall putsch, introducing a new German political figure to the world.

“Coming Generations Will Curse You in Your Grave”

In Landsberg fortress, Hitler preached to inmates while working on his seminal work Mein Kampf, dictating his thoughts to a dutiful Rudolf Hess. This historic book clearly states, “All great, world-shaking events have been brought about, not by written matter, but by the spoken word” designed for “mass effect and mass influence.” The intelligentsia “lack the power and ability to influence the masses by the spoken word” because they renounce its “real agitational activity.” They also miss a basic premise of propaganda. “The more modest its intellectual ballast, the more exclusively it takes into consideration the emotions of the masses the more effective it will be.”

After Hitler left prison, his movement lost leverage, but he continued to make public speeches, appealing mainly to farmers and workers who sought simple answers to complex problems through the Nazi Party. Yet, only a minority of Germans supported the National Socialists. They received 6.5 percent of votes in the 1924 election, less than 2.9 percent in the 1928 election, and Hitler lost the 1932 presidential election. He never received more than 37 percent of the popular vote. Everyone thought the Nazi Party was doomed. But through backstage political intrigue, Hitler convinced President Paul von Hindenberg to appoint him chancellor in 1933.

The outraged General Ludendorff wrote the elderly president a prophetic letter: “By naming Hitler as Reich chancellor, you have delivered up our holy Fatherland to one of the greatest demagogues of all time. I solemnly prophesy to you that this accursed man will plunge our Reich into the abyss and bring our nation into inconceivable misery. Because of what you have done, coming generations will curse you in your grave.”

“Our Last Hope: Hitler”

Ascetic Hitler understood the power of place and theatrics in influencing the masses. “My surroundings must look magnificent. Then my simplicity makes a striking effect.” He dressed simply, ate simply, and lived simply—but made Nazi displays grandiose. Albert Speer thought that all the esoteric rituals were “almost like rites of the founding of a church.”

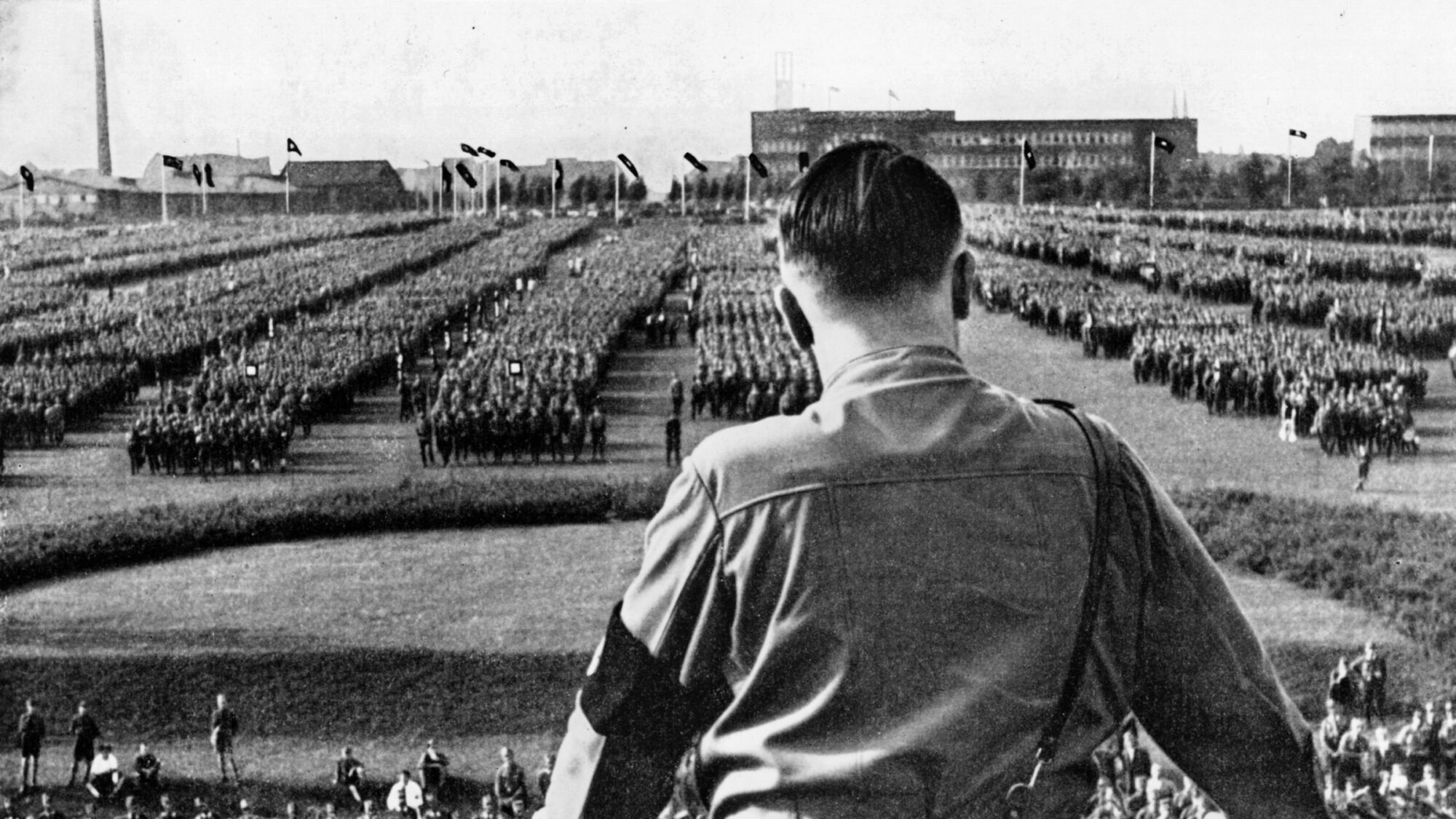

Hitler and Goebbels supplied the German masses with endless parades, rallies, and festivals such as the staged 1936 Olympics, annual Octoberfest in Munich, and the extravagant Nuremberg Rally. Openings usually included thousands of solemn Nazi soldiers doing the macabre goosestep. Drums rolled and trumpets blasted. A male chorus chanted heroic anthems. The electric atmosphere included everything from floats and colorful costumes to banners, flags, and enormous eagles. Smoke and torchlight parades trailed on for hours, often after sundown for a quasi-mystical effect.

The operatic spectacles of Richard Wagner served as a blueprint for Hitler’s rhetoric with their war, struggle, and mythological themes. Hitler attended productions of Wagner’s operas whenever possible and patterned the hypnotic tones of speeches after them.

When Hitler unsuccessfully ran for president against Hindenberg in 1932, red posters with Gothic lettering and simple slogans surfaced everywhere. One exclaimed: “Our Last Hope: Hitler,” while others read “Work, Freedom, and Bread!” and “We Are Creating the New Germany! Remember the Victims.” Hitler became the first politician to use an airplane, stumping at 20 rallies to almost a million Germans. Goebbels pushed slogans like “the Führer over Germany” in which Hitler seemed to descend from the clouds like some god. Between April and November he spoke at 148 mass rallies to cheering crowds of up to 40,000.

Goebbels also enlisted radio and movies in the struggle. One poster praised: “All Germany listens to the Führer with the People’s Radio.” By 1934, over six million radios existed in Germany, and during the war over 70 percent of homes had one, more than any other country. Loudspeakers were placed in schools, factories, and public squares. In 1933 alone, Hitler delivered 50 radio speeches but felt uncomfortable in a studio without a visible mass audience and seldom used the medium after 1933. The Nazis also made hundreds of propaganda films such as The Eternal Jew, Olympia, and Triumph of the Will in which Hitler strutted past 100,000 soldiers.

The Speeches of Adolf Hitler

Hitler wrote his own speeches, sometimes waiting until the last minute, and dictated to secretaries while planning melodramatic gestures. He once told a journalist, “When I compose a speech, I visualize the people. I can see them just as though they were standing before me. I sense how they will react to this or that statement, to this or that formulation.”

Speeches were often staged at night in large auditoriums with controlled lighting effects. He was probably influenced by noted German playwright Hanns Johst, who said, “Lighting changed forms, heightened them, dissolved them and turned them into fairy tale magic.” Entrances were carefully staged with delays, and Hitler usually left immediately after speaking, accompanied by stirring music.

Before speaking, Hitler became jittery, fingering cap and gloves, slouching down in a seat with head between hands. But then a miraculous transformation happened. He usually began very slowly in a tenor voice, sometimes for 10 or 15 minutes, searching for words and intuitively sizing up an audience. Then all hell broke loose. A secret wartime report said that his voice would rise, tempo increase, and get louder and louder, shrieking curses and foul names to frenzied audiences. Rhythms were liturgical, peppered with slogans, repetition of words and patriotic language such as “One people, one nation, one leader.”

Content was designed to arouse basic instincts rather than the intellect as illustrated by the following seething snatches from speeches in the 1920s. “There will be no peace in the land until a body is hanging from every lamp post”; “On one point there should be no doubt: we will not let the Jews slit our gullets and not defend ourselves”; or “Let us be inhumane! But if we save Germany, then we will have accomplished the world’s greatest deed. Let us do injustice! But if we save Germany, then we will have eliminated the world’s greatest injustice. Let us be immoral! But if our folk is saved, then we will have opened the way for morality again!”

Hitler wore a military uniform while speaking to give him confidence, like any actor playing a role, exploiting time, space, and rhythmic speech patterns for maximum emotional effect. Few denied his power of persuasion over mass audiences. After ranting for hours, his breathing grew heavy. He became drenched with sweat. Sometimes he nearly collapsed and would be helped off the stage while frenzied audiences gasped in awe at their savior. His valet wrote that after these exhaustive orations he would “wrap Hitler in a thick blanket and escort him home. There he took tablets to prevent getting a chill, drank tea laced with a log of cognac and took hot baths.”

Yet, the magic vanished backstage. The insecure Hitler, always surrounded by scores of SS guards, became just another face in the crowd, eating chocolates and cream cakes, watching Mickey Mouse cartoons, and retelling the same threadbare stories. His favorite American movie tune was “Donkey Serenade,” and he liked to whistle “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf.”

Who Was the Real Hitler?

So who was the real Adolf Hitler, the cult figure who, in the end, failed as an artist, failed as a militarist, failed as a political leader? Nobody ever knew, even the Führer himself. Albert Speer recalled, “In retrospect, I am completely uncertain when and where he was ever really himself, his image not distorted by playacting.”

General Alfred Jodl, who saw Hitler nearly every day, wrote to his wife during the Nuremberg Trials: “Who will boast of knowing another when that person has not opened to him the most hidden corners of his heart? Thus I do not even know today what he thought, knew, and wanted to do, but rather only what I thought and suspected about it.”

Hitler’s tragic flaw? He failed to heed Nietzsche’s sage advice: “I am that which must overcome itself again and again.” Such a stark awakening might have saved the lives of 50 million people.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments