By Pat McTaggart

In 1976, the Soviet city of Tula joined an elite group of nine other Soviet communities designated as “Hero Cities.” The designation was an official recognition of the courage of Tula’s defenders and of their efforts in stopping the Germans during World War II. Two other cities joined the list before the award was officially discontinued in 1988.

Tula has been in existence since the 14th century, and its citizens have been no strangers to warfare since its inception. It was a minor fortress during the Middle Ages, and in 1552 it successfully resisted a Tatar siege. In 1607, Ivan Bolotnikov, leader of a rebellious army composed of malcontents, peasants, Cossacks, outlaws, and other disaffected groups bent on exterminating the ruling class, held out for four months in the fortress before surrendering to the czar’s army.

The town’s fortune took a dramatic turn when it was visited by Peter the Great in 1712. Peter commissioned the Demidovs, a major weapons manufacturing family, to build the first real armaments factory in Russia at Tula. Within a few decades, Tula was the greatest ironworking center of Eastern Europe, turning out thousands of weapons for the Russian Army each year.

Throughout future decades, even after the Demidovs moved their manufacturing center to the Urals, Tula remained a center of heavy industry and war matériel production. By 1941 the armaments and ironworks factories were a major contributor to modernizing the arms of the Red Army. In the winter of that year, however, the city and its citizens would make the ultimate contribution to the Motherland.

“2nd Panzer Army Will Attack Through Tula as Soon as Possible”

During the first hours of June 22, 1941, the German Army stood ready for its greatest offensive of the war. More than 3,000,000 German and allied troops from Hungary, Romania, and Finland, clustered in three Heeresgruppen (Army Groups), were about to invade the Rodina, the Motherland, the Soviet Union.

As German spearheads thrust eastward, seizing a large expanse of territory and inflicting horrendous casualties on the defenders, Tula’s armaments factories continued to pour out weapons for the Red Army. After long, grueling hours of producing rifles and pistols, the workers trudged out of their workplaces and, in hushed voices, discussed the latest reports from the front. Soviet propaganda called for everyone to give their all for the defense of the Motherland, and many of the workers wondered how long it would be before they received notice to report for military duty. Tula was no different than the other towns standing in the way of the Germans, and workers often went straight from a grueling day at the armaments factories to hours of drilling and weapons training.

By early October, the German 2nd Panzer Army under General Heinz Guderian threatened Tula during an all-out effort to capture the Soviet capital of Moscow. Guderian received the following order from OKH (Oberkommando des Heeres, the German high command) on October 7: “2nd Panzer Army will attack through to Tula as soon as possible. [It] will take part in the attack on Moscow from the south.”

It was about 125 kilometers from Guderian’s position at Mtsensk to Tula. In his memoirs, Guderian admitted that there would be no rapid advance like the ones that had been experienced in recent months. The snow that had fallen during the night of October 6 was melting, and dirt roads that had previously been passable quickly turned into quagmires, causing the Germans to use a greater rate of fuel as the armored and mechanized units slogged their way through the mud.

Defending the Mozhaisk Line

On the Russian side, a shakeup in command was under way. General of the Army Georgii Konstantinovich Zhukov was summoned by Soviet Premier Josef Stalin to Moscow from his post at Leningrad. The Soviet leader blamed Zhukov’s predecessor, Col. Gen. Ivan Stepanovich Konev, for a disastrous performance of the Western Front, and on October 10 Zhukov was given Konev’s command. At the same time, the reserve front was incorporated with the Western Front, which made Zhukov responsible for the defense of Moscow against attacks from General Hermann Hoth’s Panzer Group 3, General Erich Hoepner’s Panzer Group 4, and Guderian. Although Stalin wanted to put Konev on trial, Zhukov pleaded with the Soviet dictator to allow him to make Konev his deputy commander instead—a plea that was surprisingly granted.

When he arrived at the Mozhaisk Line, a series of defenses about 113 kilometers southwest of Moscow, Zhukov found the defenses “absolutely insufficient.” In a 1966 television interview that was banned for decades, he said the frontline commanders did not have a complete certainty that they would be able to hold the enemy.

“It was an extremely dangerous situation,” he said. “In essence, all the approaches to Moscow were open. Our troops on the Mozhaisk Line could not have stopped the enemy if he moved on Moscow. I telephoned Stalin. I said the urgent thing is to occupy the Mozhaisk Line, as in parts of the Western Front, in essence, there are no [Soviet] troops.”

Stalin responded by gathering STAVKA (Soviet High Command) reserve units and integrating them with units already on the line to form a new 5th Army under General Dmitri Leliushenko. He also took Leliushenko’s old command, the 1st Guards Rifle Corps, and used it as the nucleus around which the 26th Army was reformed under the command of the former chief of staff of the Central Front, Lt. Gen. Grigorii Grigorivich Sokolov. Sokolov’s orders were to stop Guderian on the Tula-Orel axis.

Guderian’s Advance Through the Mud

While Soviet and German forces slugged it out west of Moscow, Guderian was trying to press forward through the mud. Wheeled vehicles had to be pulled by tracked vehicles—a process that increased wear on both. Logistics were a nightmare due to the atrocious road conditions, and the Luftwaffe was called upon to air drop essential materials before Guderian could resume his offensive.

To Guderian’s north, General Heinrich Vietinghoff-Scheel’s XIII Army Corps captured Kaluga on October 12. This resulted in an important consequence for the city of Tula. The 238th Rifle Division was stationed there and along with worker units was preparing defensive positions outside and on the edge of the town. With Kaluga’s fall, part of the southern wing of the Mozhaisk Line was unhinged. To block a further German advance, the 238th was ordered to Aleksin, about 50 kilometers northwest of Tula, to defend the road running from Kaluga northeast toward Moscow. The move left only NKVD troops and the 732nd Antiaircraft Regiment to defend the city if it were attacked.

Another disaster hit the Western Front when a combat group under the command of Major Franz-Josef Eckinger captured a bridge at Kalinin, about 170 kilometers northwest of Moscow, on October 14. A bridgehead was soon formed north of the Moscow Reservoir, causing another wave of panic in the Soviet capital. The situation was exacerbated by the capture of the town of Mozhaisk on October 19 by General Georg Stumme’s XL Motorized Corps. Moscow was now threatened from both the west and the north, with Guderian ready to resume his offensive against Col. Gen. Andrei Ivanovich Yeremenko’s Briansk Front.

Guderian, bolstered with forces returning after liquidating the last Russian pockets left over from the earlier week’s battles, attacked on October 22 with Maj. Gen. Hermann Breith’s 3rd Panzer and von Langermann’s 4th Panzer, part of General Leo Freiherr Geyr von Schweppenburg’s XXIV Motorized Corps, hitting the 26th Army along the Zusha River in the Mtsensk area. The initial attack failed, but a second attack by Breith breached the line northwest of the town. The same day, Brig. Gen. Walter Nehring’s 18th Panzer Division, part of General Joachim Lemelsen’s XLVII Motorized Corps, took the town of Fatesh on the Kursk-Orel Highway, securing Guderian’s southeastern flank.

Fortifying Tula

Two days later the Panzer Brigade of the 4th Panzer Division under Colonel Heinrich Eberbach reached Chern, about 95 kilometers southeast of Tula. The danger to Tula could no longer be kept from the people, although rumors of the approaching Germans were already rampant. On October 22, as Eberbach’s panzers were heading toward Chern, the Tula Defense Committee was officially organized with the First Secretary of the Party of the Tula District, V.G. Zhavoronkoy, as its leader. The following day a 1,500-man Tula Worker’s Regiment was formed.

The garrison commander, a Colonel Ivanov, signed an order mobilizing inhabitants between the ages of 17 and 50 to start building entrenchments, antitank ditches, minefields, and strongpoints that would eventually surround the city. Some of Tula’s industrial plants were dismantled and shipped east as part of an overall Soviet strategy to keep Russian industry safe and out of German hands, but weapons and munitions production were still in full swing in the factories that remained.

The 50th Army, commanded by Maj. Gen. Arkadii Nikolaevich Ermakov, was in the process of taking up positions to defend the area around Tula as the Germans advanced. The Tula Defense Committee coordinated its actions with Ermakov and ordered the Worker’s Regiment to take up positions on one side of the Orel-Tula Highway, while the 156th NKVD Regiment occupied the other side. A vastly understrength 260th Rifle Division was sent to defend positions on the highway leading to Voronezh.

Inside the city, tank destroyer groups were formed. They were expected to meet and destroy German armor with an assortment of gasoline-filled bottles and antitank grenades. While these units continued to train, the civilians of Tula kept digging defensive lines, planting mines and stringing barbed wire to protect antitank guns from being deployed at key points.

“Advance at Full Speed and Take Tula”

Guderian entrusted the vanguard of the drive to Tula to Colonel Eberbach, whose battle group now comprised most of the armor of the XXIV Motorized Corps. He was supported by the Infantry Regiment Grossdeutschland, which, due to lack of fuel, mounted one battalion on Eberbach’s panzers for the advance. Eberbach’s orders were deceptively simple: “Advance at full speed and take Tula.”

The so-called advance at full speed turned into an exhausting duel, not only with the Russians, but also with the Russian weather. Snow followed by rain turned the only good road into a virtual bog that placed a great deal of stress on the German motorized vehicles. Once again, tracked vehicles had to be used as tow vehicles to help wheeled units keep up. Supply units were left far to the rear, and many vehicles had to be abandoned due to burned out engines.

Despite the weather and sporadic Soviet resistance, Eberbach’s advance column managed to reach an area about 32 kilometers south of Tula by October 28. Reports coming back from the front spurred greater efforts to strengthen the city’s defenses, and Ermakov sent what little he could to Ivanov and the Tula defense forces. Several antitank and antiaircraft weapons came as a welcome addition to the defenders as the Germans resumed their advance on October 29.

Eberbach’s units covered 28 kilometers that day, his men making almost superhuman efforts to keep their vehicles running in the morass that could hardly be called a road. The panzers and mounted infantry brushed aside scattered Soviet resistance as they passed through the small villages that lay along the route. Yasnaya Polyona, the final resting place of novelist Leo Tolstoy, fell by mid-afternoon, and Kosaya Goya, the last obstacle before Tula, fell soon after.

It was an exhausting trek through the mud, but by early evening only four kilometers separated the Germans from their goal. Sensing an opportunity for a coup de main, Eberbach proposed launching a night attack on the city.

The 2nd Company of the Grossdeutschland moved forward, planning to take an industrial area on the town’s southern outskirts to use as a jumping-off point for the main attack. As the unit moved forward, it was met with withering fire from Soviet outposts. Other units met the same welcome from the Russian defenders, and the supporting panzers soon became targets of the antitank guns and individuals throwing gasoline-filled Molotov cocktails as they tried to move through enemy defenses.

Casualties among the Germans began to grow as the attack continued. The commander of Grossdeutschland’s 2nd Company, 1st Lt. Brockmann, was wounded and was succeeded by 19-year-old 2nd Lt. von Oppen. With 60 effective fighting men left in the company, von Oppen stormed a workers’ settlement. The Germans slowly pushed back the defenders, but resistance was heavy enough to convince Eberbach that a surprise thrust into Tula was not possible. Deciding to wait for reinforcements, he postponed the main attack until 5:30 the following morning.

Tula Ready for the Germans

By the 30th, however, the civilian and military defenders of Tula were ready for the Germans. The town was cut in half by the Upa River, and its northern section was again divided by the Tulista River, a tributary of the Upa. Antitank ditches bordered the southern outskirts and were anchored on both the east and west sides by the river. Another antitank ditch stretched from the Upa to the Tulista on the northeast section of town. Minefields backed by antitank strongpoints and machine-gun nests covered the most likely avenues of advance, turning those areas into dangerous killing grounds.

Reinforcements also had arrived to bolster the defense of the city. On the morning of the 30th, the headquarters of the reconstituted 260th Rifle Division, commanded by Colonel N.V. Revyakin, entered the town. The 732nd Air Defense Regiment (Major M.T. Bondarenko) was also receiving more of its units to man the strongpoints. Ermakov, realizing the danger posed by Eberbach’s thrust to the city, established the Tula Defense Zone, funneling the depleted units of the 154th, 173rd, 217th, and 290th Rifle Divisions to shore up the flanks in the Tula vicinity, and Maj. Gen. Vasilii Stepanovich Popov was appointed area commander.

At precisely 5:30 am on October 30, German artillery opened up on Tula’s defenses. In his memoirs, the commander of the Tula Worker’s Regiment, Anatoly Gorshkov, recalled waiting for the Germans to advance.

“The morning of October 30 found the regiment in the trenches,” he wrote. “It was tedious and there was a cold autumn rain. We already had intelligence reports that the Germans were preparing to attack. After the German bombardment, we heard a heavy low buzz and then saw the tanks.”

The men of Grossdeutschland advanced as soon as the bombardment ceased, supported by panzers from the 3rd Panzer Division. It was hard going, with Soviet defenders entrenched behind strong barricades. Combat took place in the workers’ quarters in Krasny Perekop, with hand-to-hand fighting clearing buildings room by room. With the panzers confined to the narrow streets, it was up to the infantry to push the Russians back.

The German Infantry Take Hold

By early afternoon there was fierce fighting in the trenches in the Rogozhinsky District of the city. Workers’ units supported by Bondarenko’s antiaircraft guns gave as good as they got, preventing a German breakthrough. At Krasny Perekop, the Soviet defenders took up a new line of defense in a park and behind cemetery walls, stopping the Germans in that quarter.

The final straw for the Germans on that bloody day came around 3:30 pm, when tanks from Colonel I. Yuschuka’s 32nd Tank Brigade arrived on the battlefield. They immediately engaged Breith’s panzers, causing them to slowly pull back from the fight, which bogged down the entire German assault.

Eberbach and Colonel Walter Hörnlein, commander of Grossdeutschland, decided to make one more attack. Forming up along the Orel-Tula Highway, the Germans moved forward again at 4 pm. They tried to infiltrate the Soviet line on the southern outskirts of the city by attacking through the Vsekhsviatsky Cemetery, but workers’ units occupying the area held firm. The attack then shifted to the area around Tula’s Weapons-Technical School, achieving modest success before being stopped by another workers’ battalion.

Artillery and machine-gun fire ripped the Russian lines, but the hodgepodge mixture of defending units holding the outskirts of the city would not break. As darkness fell, Eberbach called off the attack and ordered his men to form defensive lines of their own.

The Soviets claimed to have destroyed more than 30 tanks in addition to killing hundreds of Germans during the attack. Late in the evening the rest of Yuschuka’s tank brigade arrived in the city, bringing its strength to seven T-34s, five heavy KV-Is, and 22 older T-60s. They would be enough to keep Breith’s panzers at a safe distance for days to come.

More Soviet units made their way to the Tula sector during the night. A battery of rocket launchers, which the Russians called Katyuscha (Little Catherine) and the Germans soon nicknamed Stalin’s Organs, came to support the defenders, and the 413th Rifle Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Aleksei Dmitrievich Tereshkov, arrived at the northern Stalingorosk Railway Station to bolster the line there.

In the early hours of October 31, the rocket launchers announced themselves for the first time. The howl of the rockets followed by mass detonations in a small target area stretched German nerves to the limit.

Infiltration attacks by Soviet troops against Germans clinging to positions in buildings on the outskirts of the city followed the barrage. In a light rain, the Russians attacked in platoon and company strength. The semi-darkness of the fall morning added to the eerie, almost ghost-like Russian advances as the Germans saw forms appear, then disappear, in the mist and fog. Shots rang out all along the line, some aimed at human targets and others aimed at nothing but shadows.

Supported by artillery from the 447th Artillery Regiment located on the northern fringe of Tula, the Russians closed on the German positions. Some of Yuschuka’s tanks also infiltrated the thinly held German line and then turned around, hitting some of the Grossdeutschland units from the rear. The attacks continued throughout the day, but counterfire from a German artillery battalion located near Kosaya Gora finally forced the Russians to withdraw.

German infantry around Tula were holding on by their fingernails, weakened by the previous two days of combat and receiving nothing in the way of replacements. Meanwhile, the Soviets got another boost as Colonel M.P. Krasnopitsev’s 437th Rifle Regiment entered the city.

The Russian Counterattack

As the Soviets funneled more men into the area, including remnants of the 154th and 217th Rifle Divisions, the Germans called for Luftwaffe support to soften up the Russian defenses. When the bombers flew over the city, they were met with a curtain of antiaircraft fire. Several aircraft were shot down, and the remaining planes did little damage as they swerved to avoid the air bursts that dotted the sky.

German infantry units were slowly moving forward to reinforce the men of Grossdeutschland, but the weather made it difficult. Falling temperatures, the seemingly endless mud, and the icy rain made life extremely uncomfortable for the men, who were still clad in their summer uniforms.

“The mud is getting thicker,” a medical officer wrote in his diary. “We are sweating in spite of the cold. We break for 10 minutes, then we start to freeze immediately. Everybody is sick and weak. Then one [soldier] lies in the mud. He can go no further.”

The defenders of Tula were not about to wait until the Germans regained their strength. On November 1 the Soviets again attacked the thinly manned German line. The tanks of the 32nd Brigade led the way supported by regular infantry and workers’ units. When the Russian tanks attempted to break through the point where the Grossdeutschland I and II Battalions were linked, the beleaguered Lieutenant von Oppen, still commanding the 2nd Company, yelled for a sergeant to follow him. The two men worked their way behind the tanks, which had outrun their infantry support.

Von Oppen boarded one of the tanks and disabled its turret with a grenade bundle. Another tank was disabled by an antitank gun, causing the remaining Soviets to retreat. In touch-and-go actions all along the front, the Russian attack was finally brought to a halt, leaving both sides reeling.

The Germans Strengthen Their Foothold in Tula

Tula, the southern gateway to Moscow, proved too hard to take at the moment. The 2nd Panzer Army was strung out all along the southern front, and there were few good roads to support its efforts. Guderian, already believing the only way to unhinge this anchor of the Soviet line was to isolate it by a flanking movement, ordered most of the XXIV Motorized Corps to take Dedilovo, about 21 kilometers southeast of the city. Although not as good as the Tula Highway, Dedilova had a road connection that also headed north. If the town could be taken, Guderian’s motorized forces could use the road to move north and then west, cutting Tula’s lines of supply and communications.

As von Schweppenburg’s panzers approached Dedilovo, they ran into heavy resistance from 50th Army units defending the approaches to the town. To von Schweppenburg’s right, the divisions of General Karl Wiesenberger’s LIII Army Corps moved toward the town of Teploye.

While the infantry and tanks engaged the 50th Army east of Tula, the German forces remaining in front of the city continued to try to widen their foothold. On November 3, a combined panzer-infantry attack pushed toward a stadium and a cemetery on the southern outskirts. NKVD units supported by smallcaliber antiaircraft guns repelled the attack.

Elements of the German 31st, 131st, and 296th Infantry Divisions were finally arriving to reinforce Grossdeutschland, but the Soviets were also receiving more men in the form of Maj. Gen. Aleksei Dmitrievich Tereshkovo’s 413th Siberian Rifle Division, which was rushed to Tula by train. When the Germans attacked again on November 5, they ran into heavy fire but made some successes including taking the village of Lower Kitaevku, four kilometers southwest of Tula. Supported by artillery and Luftwaffe bombers, the infantry then moved on the nearby village of Mikhalkov but were stopped by workers’ units and elements of Bondarenko’s 732nd Air Defense Regiment.

During the next couple of days, temperatures plummeted, freezing the muddy earth. The freeze was a two-edged sword. On the one hand, truck and mechanized vehicles could move faster, as could the infantry units that had sometimes trudged through ankle- and knee-deep mud. The downside was the inadequate German field uniform, which was not made for the frigid temperatures. Winter clothing had not yet arrived, nor would it for most troops, and the Russian winter was fast approaching. If Moscow were to be taken, it had to be done soon, yet Tula and other key cities in the Moscow Defense Line refused to fall.

The cold did not stop the Russians from trying to regain territory in Tula’s southern sector. Units of Tereshkovo’s 413th Rifle Division supported by artillery hit the Germans hard and claimed to have destroyed a panzer and two companies of infantry. Around the Tula Station, Soviet forces strove to punch a hole in the German line but were repulsed with substantial losses.

German forces counterattacked and began an advance on the village of Malevka, two kilometers southeast of Tula. Soviet resistance stiffened as the Germans neared the village, causing the advance to stall and eventually grind to a halt. The Germans then took up defensive positions, forming another line that threatened the city.

T-34s Cause a Rout

With the ground hardening, Army Group Center began a redeployment for the next phase of operation. General Georg-Hans Reinhardt’s (Reinhardt replaced Hoth on October 25) 3rd Panzer Group moved between Hoepner’s 4th Panzer Group and General Adolf Straus’s 9th Army with the purpose of striking directly toward Moscow from the east. Meanwhile, Guderian’s 2nd Panzer Army would continue to hammer Tula and the other defenses guarding Moscow from the south and open the way for an advance on that sector.

The German redeployment did not go unnoticed. After conferring with his intelligence officers, Zhukov ordered a series of preemptive attacks to disrupt the enemy’s plans. While Soviet forces moved against the Germans west of Moscow, the 49th and 50th Armies began their own mini-offensive against Guderian.

General Karl Weisenberger’s LIII Army Corps had run into heavy resistance in front of Teploye. According to Guderian the Soviet forces consisted of two cavalry and five rifle divisions plus a tank brigade. The corps commander requested additional forces, and Guderian ordered von Schweppenburg to disengage and head toward Teploye to support the infantry. The disengagement was delayed when new attacks from the Tula sector hit von Schweppenburg’s flank. Despite the attacks, the panzers were able to reinforce Weisenberger. Teploye fell on November 13, and the Soviet defenders were pushed south toward Yefremov.

Meanwhile, on November 11 a Soviet force consisting of a cavalry and two rifle divisions hit the 31st and 131st Infantry Divisions northwest of Tula. The fighting, much of it hand-to-hand, took a heavy toll on both sides before the Russians withdrew to their lines five days later.

Typhoon entered its second phase on a clear and frosty November 15. Colonel Eberbach, now down to only 50 serviceable panzers, continued to support the LIII Army Corps, which ran into increasing resistance as it moved toward its goal of taking control of the Elets-Moscow Highway. If Guderian could capture the roadway, he would have an alternative in advancing on Moscow while bypassing Tula.

On November 17 the impossible occurred. Maj. Gen. Friedrich Mieth’s 112th Infantry Division was hit by a newly arrived Siberian rifle division while also being attacked by Soviet tanks, many to them T-34s. It was the first time the division had encountered the T-34, and German antitank gunners watched in horror as their 37mm shells bounced off the Russian armor. Combined with the Siberian attack, the division was swept up in what amounted to a rout that only ended with the intervention of the 167th Infantry Division, which was able to stop the Soviets.

“It was the first time such a thing had occurred during the Russian Campaign,” Guderian wrote in his memoirs. “It was a warning that the combat ability of our infantry units was at an end and that they should no longer be expected to perform difficult tasks…. We are only nearing our final objective step by step in this icy cold and with all the troops suffering from the appalling supply situation….”

Pushing Past Tula

Because of the steadfast defenders of Tula, Guderian’s supply lines would be stretched even farther as he pushed eastward to flank the city and continue his offensive, which had already lost two precious days fending off the Russian attacks. On November 18 the 2nd Panzer Army was able to continue its attack. The XLVII Motorized Corps struck the Yefremov area southeast of Tula while the LIII Army Corps drove east and northeast toward Venev and Uzlovaya. West of Tula, the XLIII Army Corps pushed north toward Kaluga, where it hoped to make contact with the 4th Army.

Tula continued to be the sticking point—a spear jutting into Guderian’s line. Von Scheppenburg’s corps, now consisting of the 3rd, 4th, and 17th Panzer Divisions, Grossdeutschland, and the 296th Infantry Division, was given the task of breaking that spear as other units of the 2nd Panzer Army advanced. To accomplish his mission, von Schweppenburg planned to use Grossdeutschland and the 296th as a blocking force on the city’s southern sector while his panzer divisions moved up Tula’s eastern and western defenses in an effort to cut the city’s supply lines in the north.

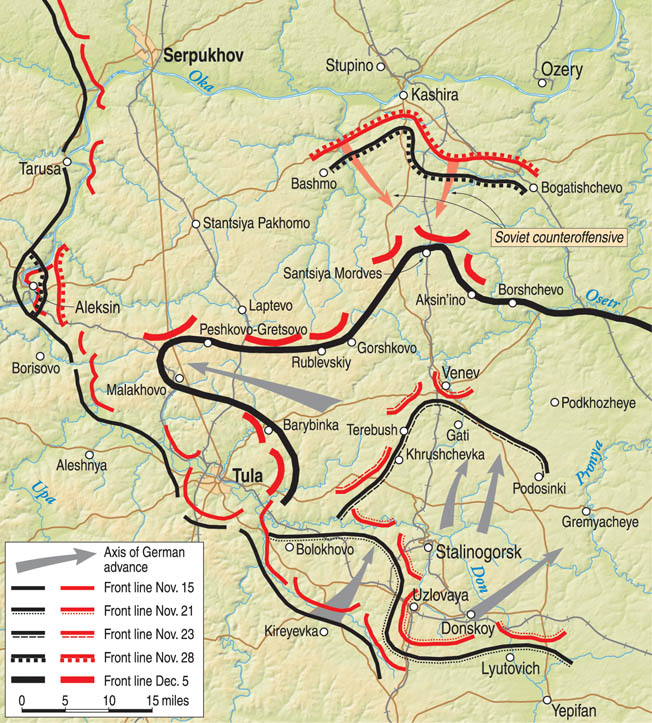

The southern lines at Tula became somewhat stagnant as the panzers strove to isolate the city from the north. Supporting infantry from the divisions moved at a snail’s pace, no more than five to 10 kilometers a day. Despite the freezing conditions, the German thrust was making some progress, shaking the Soviet lines as Dedilovo and Epifan fell on the 18th, followed Bolokhova on the 19th. Von Schweppenburg was also helped when Weisenberger’s LIII Army Corps took Uzlovaya on the 21st, anchoring Guderian’s southeast flank.

With those goals reached, von Schweppenburg turned to support the attack on Venev, about 50 kilometers northeast of Tula. Ermakov responded by sending small-caliber antiaircraft units from other areas to help defend the city. The Soviet general had done a relatively good job with the 50th Army, but he was not doing well enough as far as Moscow was concerned. According to higher headquarters’ observations, his actions to counter the German attacks were just too slow. These reports did not bode well for his future.

Besides defending the easiest southern approach to Moscow, there was another reason to hold Tula. A massive counterattack was being planned for the first week of December to bring an end to the German threat to the capital. Reserve armies were already massing behind the lines, including several divisions of the feared Siberians, but STAVKA did not want to release any of them prematurely. In the Tula sector, the Red Army needed a man who had proven himself capable of both defensive and offensive capabilities—a man who had already proven those abilities on the field of battle. Field Marshal Boris Shaposhnikov, the chief of the Red Army General Staff, thought he had just the person to fill that position.

Ivan Boldin Commands the 50th Army

On a bone-chilling November morning, Lt. Gen. Ivan Vasilievich Boldin, now fully recovered from his previous ordeals, was summoned to Shaposhnikov’s office. The marshal told Boldin the Germans were still bent on taking Moscow and that the onslaught was continuing despite the weather and heavy enemy losses. He then motioned for Boldin to look at a large operational map.

“Here!” the Marshal said, jabbing his finger at the map. “Hitler has thrown crack units into the Tula region…. Now the enemy is firing on Tula from the area of the Kosogorsk metallurgical factory [in the city’s southwest suburbs]. His aim is to seize Tula and convert it into a bridgehead for an attack on Moscow.”

Shaposhnikov then told Boldin he wanted him to take command of the 50th Army. The marshal left the new army commander with words that both oversimplified and cautioned Boldin about his daunting task.

“I think the mission is clear,” he said. “Do not forget that Hitler has entrusted the experienced combat general Guderian with the seizure of Tula.”

Boldin arrived in Tula on November 22. His predecessor was relieved and then arrested, but unlike many Soviet generals who had suffered the same fate in the first six months of the war, Ermakov was not executed. After a period of “rehabilitation” in a penal unit, he served as an army and corps commander later in the war.

The new commander of the 50th Army wasted little time in taking on his new duties. He met with commanders, gave orders to strengthen the line in the most precarious areas, and built up reserves by stripping support units to the bone. Bolding had already been trounced by Army Group Center twice. He was resolved that it would not happen a third time.

“Our Most Important Task Was Now the Capture of Tula”

Although the Germans were running out of steam, the situation at Tula and east of the city was still critical. Nehring’s 18th Panzer Division had taken Efremov, about 110 kilometers southeast of Tula, on November 20, lengthening the flank of Guderian’s panzer army. A reconnaissance battalion drove another 10 kilometers to the village of Skopin. It was the farthest east that Army Group Center would ever get. All in all, Tula was very nearly surrounded, albeit by severely weakened German forces, while the tentacles of the 2nd Panzer Army continued to look for a way to break to the north.

The Germans continued to press on. Mikhaylovka, southeast of Tula, was taken by Maj. Gen. Friedrich-Wilhelm von Loeper’s 10th Motorized Division on November 24, and the 17th Panzer Division, now commanded by Brig. Gen. Rudolf Eduard Licht, was approaching Kashira, about 50 kilometers north of Venev, on the 25th.The advances were impressive, but the additional ground gained stretched Guderian’s supply lines even farther. It also left holes in the line, which meant that threatened Russian units like the 239th Siberian Rifle Division were able to slip away from the 29th Motorized Division near Epifan, southeast of Tula, with most of their men.

Guderian knew his men were suffering, but he continued to push them while privately expressing his own doubts of success. “The icy cold, the wretched shelters, the shortage of clothing, the high losses of men and equipment, the lack of heating fuel made the conduct of battle a chore,” he wrote.

Striking out farther to the north and east would accomplish nothing new, and the German panzer commander knew it. “Our most important task was now the capture of Tula,” he wrote in his memoirs. “Until we were in possession of this communications center and its airfield, we had no hope of continuing to advance northward or eastward.”

Guderian planned for one more attempt to take the city, ordering the XXIV Motorized Corps to attack from the north and east, while the XLIII Army Corps attacked from the west. He wanted to coordinate the attack with an advance planned by the 4th Army, which was scheduled to begin on December 2 but was postponed until December 4.

Meanwhile, the German lines began to unravel as Soviet reinforcements continued to arrive. The 17th Panzer’s drive on Kashira was halted by the 1st Guards Cavalry Corps on November 27. On the following day, 4th Army came under heavy attack by Western Front forces, contributing to the two-day postponement of its own planned offensive. Von Schweppenburg’s troops were brought under heavy fire from Tula’s artillery as they moved slowly toward their jumping-off point, and on November 29 the XLVI Motorized Corps was pushed out of Skopin.

It was the same on other sectors of Army Group Center. Last-ditch efforts to take Moscow were being met with bitter resistance and heavy losses. The wily Zhukov trickled reserves into the line like chess pieces, throwing individual divisions into the most threatened areas while holding his reserve armies back for his massive counterattack.

Because the narrow corridor occupied by von Schweppenburg’s divisions made them easy artillery targets, Guderian refused to wait for the 4th Army’s attack. The 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions along with Grossdeutschland caught Boldin by surprise on December 2 and took several 50th Army advanced positions. To the east, the 31st and 296th Infantry Divisions also made some progress, striving to meet the XXIV Motorized Corps and cut off Tula from the north.

Final Relief For Besieged Tula

On December 3, in blizzard conditions with temperatures well below zero, the Germans cut the Tula-Serpukhov-Moscow Highway and also severed the Tula-Moscow rail line near Revyakino. As von Schweppenburg’s panzers continued forward, the village of Kostrovo fell on December 4. The lead elements of the XXIV Motorized and XLIII Army Corps were now only 15 kilometers apart.

As the Germans pushed forward, Boldin galvanized his forces, furiously issuing orders for counterattacks in the threatened areas. They were not to be piecemeal, but well-coordinated strikes intended not only to stop the enemy but also to push him back. He ordered the 340th Rifle, 31st Cavalry, and 112th Tank Divisions supported by several tank and rifle regiments to hit von Schweppenburg on the flanks, forcing the Germans to retreat and reopening the Moscow-Tula Highway.

“We pulled back our troops and regrouped strike forces of mobile artillery and tanks,” Boldin wrote. “We knew that the enemy was dangerously overextended, and his fuel and ammunition were running low. On the evening of 4 December, we received substantial reinforcements from the Army Strategic Reserve.”

In the XLIII Army Corps sector, Brig. Gen. Gerhard Berthold’s 31st Infantry Division, at the forefront of the attack, was stopped dead in its tracks by the 194th and 258th Rifle Divisions. The German 82nd Infantry Regiment reported 100 dead and 800 cases of frostbite, with other regiments of the 31st Division suffering about the same. It was the final gasp of the 2nd Panzer Army’s thrust toward Moscow.

In his memoirs Guderian vividly recalled the effect that the Red Army and the Russian winter had on his men during those critical days of the attack. He had witnessed the frostbite, the frozen breech blocks on artillery and antitank guns, the panzer motors frozen too tight to turn over, and the abysmal conditions his troops were forced to fight in firsthand, and he knew the end of the Moscow campaign had come.

“On account of the threats to our flanks and rear and of the immobility of our troops due to the abnormal cold, I made the decision during the night of December 5-6 to break off this unsupported attack and to withdraw my foremost units into defensive positions along the general [river line] Upper Don-Shat-Upa,” he wrote after the war. “This was the first time during the war that I had to make a decision of this sort, and none was more difficult.”

It was much the same throughout Army Group Center’s front. The 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies were also forced to halt their drive on Moscow, and Red Army attacks had already forced the 9th Army to go on the defensive. Operation Typhoon had shot its bolt. During the next few weeks, it was the Red Army’s turn to take the offensive.

At Tula, Boldin ordered his men to prepare to annihilate the enemy. A new army, the 10th under future Marshal of the Soviet Union Filipp Ivanovich Golikov, joined Boldin for the counteroffensive. Because of the heavy losses incurred by the 50th Army while defending the Tula sector, Golikov would provide the main strike force with Boldin playing a secondary role.

They hit Guderian’s troops as they were starting to pull back, running roughshod over Guderian’s rear guards and creating havoc with plans for an orderly withdrawal. The 296th Infantry and 3rd Panzer Divisions were briefly able to hold ground around Tula, but within a few days Guderian had come to the conclusion that his proposed river line could not be held. Gaps were appearing all along the lines of the 2nd Panzer Army, and the retreat continued farther to the west. Except for intermittent Luftwaffe raids, Tula was out of harm’s way for the rest of the war.

The Fate of Tula and the Generals Who Fought For It

On December 25 Guderian was relieved of his command and transferred to the Army Officers Reserve Pool. He later served as General Inspector of Panzer Forces and was eventually made chief of the Army General Staff. Guderian died on May 14, 1954, in Schwangau, Germany.

Boldin continued to lead his 50th Army throughout the war, fighting at Rzhev, Vyazama, Orel, Mogilev, and the invasion of East Prussia, but the shining moment of his career was the defense of Tula in the critical days of November-December 1941. In April 1945 he was appointed deputy commander of the 3rd Ukrainian Front. His postwar career included the command of the 8th Guards Army and the Eastern Siberia Military District, ending in 1958 as a military consultant to the Defense Ministry Group of General Inspectors. He died in Kiev on March 28, 1965.

As the war shifted westward, the citizens and workers of Tula returned to their work. Replacements were brought in for those who had fallen during the fighting, and the armaments factories continued to turn out arms for Soviet forces during the war and into the Cold War.

Many of the soldiers and workers who defended Tula in November and December 1941 had died by the time Tula received its recognition as a Hero City, but those who remained still had intense pride in their role in holding the Germans at bay. In their minds, the defense of Tula and the blood shed in that defense had helped save Moscow. The designation of Hero City only strengthened that belief.

I passed through Tula at night on a train to Volgograd. I think the defence of Tula was key to the defence of Moscow and I have read Guderians book