By Allyn Vannoy

Like something out of a dream, a soldier walked into the command post. He unspooled a line of wire, hooked a field phone to it, checked the line, and handed the receiver to the officer in charge, Captain Howard Trammell, saying, “Someone wants to talk to you.” Outside, the village was being rocked by mortars and gunfire that were ripping apart Trammell’s company of armored infantrymen who belonged to Company C, 62nd Armored Infantry Battalion.

Trammell, commander of Company C, was a 24-year-old from Clay County, Missouri. Lacking money for college, he joined the National Guard in 1939 and was assigned to the 14th Armored Division at Camp Chaffee, Arkansas.

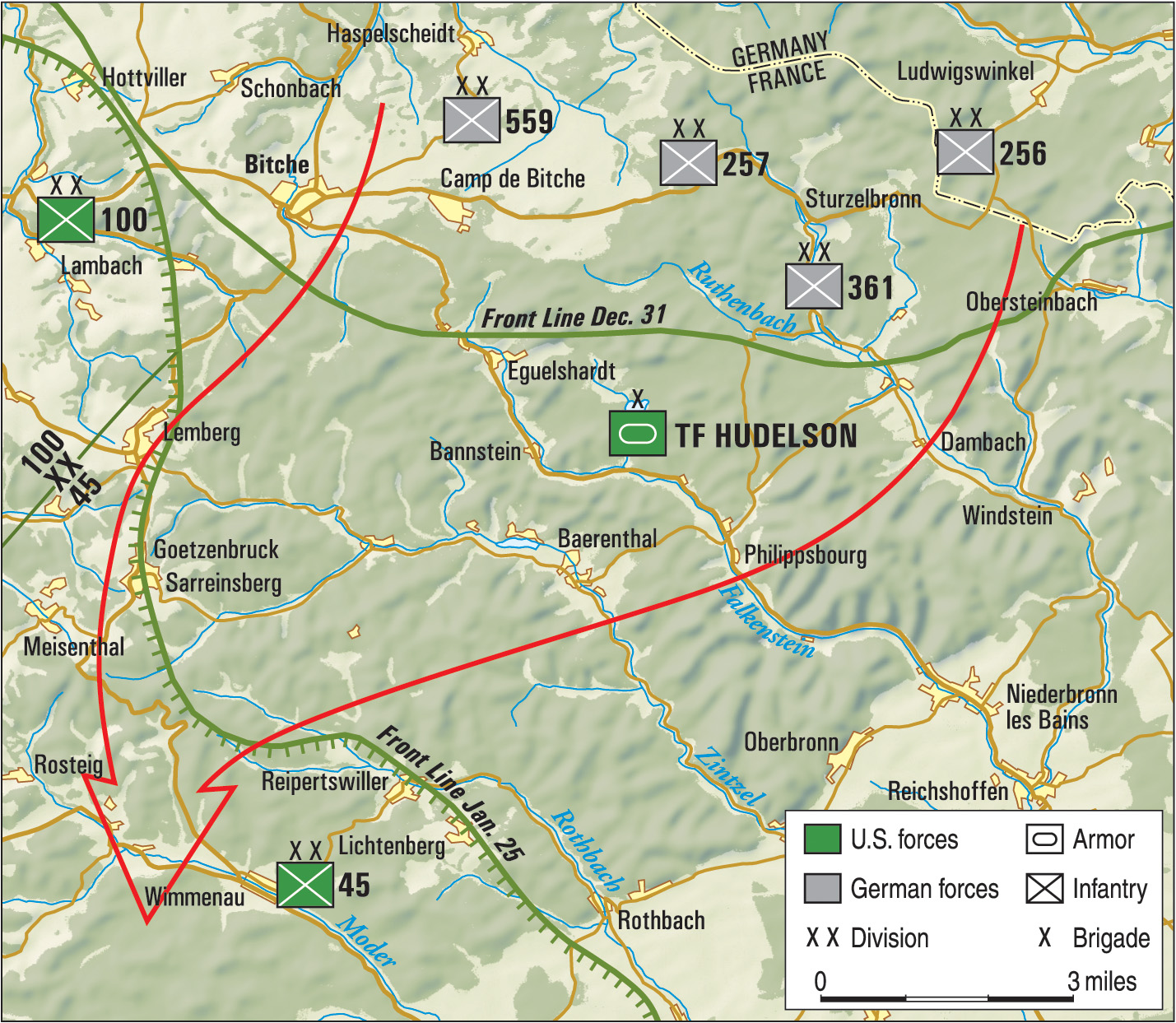

In late December 1944, Company C was part of Task Force Hudelson, which was led by Colonel Daniel Hudelson of Combat Command R, 14th Armored Division. The division comprised a mix of division and nondivision assets, including the 62nd Armored Infantry Battalion, the 94th Cavalry Recon Squadron (less Troop C), the 17th Cavalry Squadron, Company A of the 125th Armored Engineer Battalion, and Company B of the 645th Tank Destroyer Battalion. The division also contained Company B of the 83rd Chemical Mortar Battalion, a detachment from the 540th Engineer Combat Regiment, and the 500th Armored Field Artillery Battalion.

The regimental-sized task force was deployed as part of Maj. Gen. Edward Brooks’s VI Corps defense in depth across the Lower Vosges Mountains, arrayed along the French-German border. The task force’s mission was to hold a section of the Seventh Army line connecting Maj. Gen. Wade Haislip’s XV Corps and Brooks’s VI Corps.

The men of Task Force Hudelson had stitched together an elaborate defense consisting of minefields, roadblocks, and barbed-wire obstacles at key points. They established outposts and strongpoints with fields of fire laid out and artillery registered on key target areas. They also echeloned reserve forces in depth, which were to stand ready to deploy forward to reinforce any hard-pressed sectors or block any breakthroughs.

Throughout December there had been a number of indications that the Germans were preparing to attack Lt. Gen. Jacob Devers’s 6th Army Group to which Maj. Gen. Alexander Patch’s Seventh Army belonged. The interrogation of German prisoners, reports of rail movements and arrival of new forces, aerial reconnaissance, and Ultra reports all combined to create the atmosphere of an impending attack.

Devers expected the attack to occur on either New Year’s Eve or on New Year’s Day. He was aware that the Germans had amassed upward of 15 divisions for an attack by Col. Gen. Johannes Blaskowitz’s Army Group G. Seven German infantry divisions of fair to good quality were on the front line. They were backed by three panzer divisions that had been recently refitted. Three to five lower quality divisions also were available. Although not all would participate in the expected attack, it gave Blaskowitz sufficient reserves to carry out an offensive.

More than 10,000 volksgrenadiers ultimately participated in the Wehrmacht’s offensive known as Operation Nordwind. The two heaviest blows struck Maj. Gen. William Dean’s 44th Infantry Division in the center of Haislip’s XV Corps line and the 645 troops of Task Force Hudelson on the left flank of Brooks’s VI Corps. The lead elements of the assault against Task Force Hudelson, the 361st Volksgrenadier Division, would run straight into Company C.

The 62nd was put in the line from the town of Phillipsbourg to the village of Bannstein. Companies A and B occupied ground north of Philippsbourg; Company C was sent to Bannstein. Battalion headquarters was in Phillipsbourg. The battalion covered a nine-mile frontage—Company C holding five miles over twisting, heavily forested hills. The hills made radio contact extremely difficult, most communications being carried by jeep messengers or over field phones.

Bannstein was just three miles south of the German border and the Siegfried Line, astride the main road from the town of Bitche to Phillipsbourg, and 20 miles north of the Saverne Gap—the key passage through the Lower Vosges Mountains—through which Allied supplies and reinforcements had to pass to reach the upper Alsatian Plain and the French city of Strasbourg. Seizure of the pass was vital to German strategy in Operation Nordwind.

Company C was deployed with Company B to its right and the 94th Cavalry Squadron on its left. The company’s 1st Platoon was set on the left flank, to the north of the village across the Bitche road, and the 2nd Platoon on the right along the eastern edge of a small lake—Etang du Hanau. The company command post (CP) was placed in a large hotel in the village proper and under the command of 2nd Lt. Roland Adcox. Third Platoon, acting as a reserve, was housed in the village.

Though of limited effectiveness against German tanks, the five 57mm guns of the company’s antitank platoon, under Lieutenant Franklin Roesch, were sighted to cover the roads into Bannstein.

Company C was operating, like many American units, at less than full strength—short 35 men. But even if given a full compliment of 245, including cooks, mechanics, and drivers, each man would have been responsible for 108 feet of frontage. However, following the standard practice of having one platoon in reserve and two on the line, the frontage per man was closer to 240 feet. Taking into account the terrain and the winter conditions, such an area was impossible to cover. Therefore, the line platoons were assigned to key strongpoints and putting out listening posts. Positions were well dug in and reinforced with mines and trip flares.

The area around the village was heavily forested with steep, high ridges that ran in a north-south direction. The roads in the vicinity followed the forest valleys, affording numerous places for roadblocks as well as ambushes.

Given the terrain and thinly held front, circumstances provided opportunities for the Germans to infiltrate, cut communications, block support routes, and isolate American units. The seriousness of the situation was exemplified one morning when Pfc. Boyce Nichols, on sentry duty at the company CP, reported that two German soldiers had been able to walk right down the main road and up to the CP to surrender without being challenged by any of the outposts.

An unusual quietness hung over the sector on New Year’s Eve. The ground was covered with snow, and the moon made it possible to see men moving about. Hudelson’s armored infantrymen were scheduled to be relieved the following day by elements of the 70th Infantry Division, but the German offensive derailed those plans.

The German assault came without a preliminary artillery bombardment. At three minutes before midnight, 1st Platoon’s Sergeant Robert Highsmith, Private Gene J. Wacht, and Technician Fifth Grade Roy M. Gahagan were on outpost duty when they spotted a column of German soldiers marching down the Eguelshardt road. They were amazed to see the Germans marching four-abreast in parade ground fashion. Highsmith alerted his platoon sergeant, John W. Pleacher, Jr., and was told to stay put and that Pleacher would be up to take a look. But before Pleacher could come forward, an estimated two companies had bypassed Highsmith’s position. Hearing firing coming from the direction of Bannstein, the trio headed for the village. They noticed several Germans following them, but the Germans did not fire on the three, apparently thinking they were friendly. As the trio neared the village they began to receive machine gun fire from American positions but managed to reach the village unscathed.

German volksgrenadiers in winter camouflage spread out as they advance through the fog during Operation Nordwind. The goal of the German offensive was to break through the U.S. Seventh Army’s line and destroy its forces.

Trip flares were going off all over the area; the woods around Bannstein seemed to be full of Germans. The GIs in the outposts and strongpoints soon became engaged in a series of deadly firefights. Action developed into a swirling fight as both sides became mixed with little idea of who was friend or foe.

The leader of the 1st Squad, Staff Sergeant Edward Faytak, and his men were deployed in an outpost on the 2nd Platoon’s right flank, east of Etang du Hanau, near a villa where the platoon’s CP had been established. Faytak’s squad was short three men at the time. They had set up in a crawl space under a small stone building. They also had dug foxholes about 100 yards from the building facing the woods. The villa CP was to their rear, the lake to their left, and the woods and hills were in front and to the right of the foxholes.

The Germans, dressed in white snow suits, screaming and yelling, assaulted repeatedly, each time rushing forward firing their automatic weapons.

The Germans came through the dense forest bypassing elements of the 1st Platoon, under 2nd Lt. Robert Warbritton, and began firing across the open ground between the forest and the village.

In Bannstein, service and support personnel were on edge. Little information was coming from the frontline platoons, and firing, both German and American, was occurring almost within the village. Between bursts of fire the silence was punctuated by a lone German voice calling out, “Doctor.”

The 3rd Platoon, led by 1st Lt. Edwin M. Kosik, was situated in a gasthaus (inn) on the main northwest-southeast road from Bitche to Philippsbourg. Pfc. Robert W. Buntin and a number of others of the 3rd Platoon took up a defensive position in a crater to the right rear of the gasthaus. Just to the right of the crater, Technician Fifth Grade William H. Siewert manned a .50-caliber machine gun on his halftrack. Siewert was assisted by Private Joseph “Chief” Poneyestewa, a Hopi Indian from Arizona. Siewert received a head wound, and along with Poneyestewa, was eventually taken prisoner.

Trammell spent most of his time throughout the night trying to maintain contact with his platoons and giving reassurances to the surrounded 1st Platoon CP, with whom he was in radio contact, that he intended to relieve them.

During the attack, Staff Sergeant Augustine C. Bojorquez was alone in his mortar squad half-track when he saw about 30 Germans attempting to work their way up a nearby draw. Using the mortar tube and sighting over the barrel, with the tube end on the ground between his feet, raising and lowering the tube angle to get the range, he placed several rounds on the Germans, stopping them. During the action Bojorquez had the heel of his boot shot off but kept on firing. He would receive a Silver Star for his valor.

Before daylight the Germans managed to successfully infiltrate portions of the village, taking a house between the company CP and Bannstein proper, isolating the CP except by field phone.

Staff Sergeant John Lillich, one of 3rd Platoon’s squad leaders, holed up in the gasthaus, reported that daylight revealed that the Germans had suffered a large number of casualties.

Shortly after daybreak, Trammell received a call from the battalion commander, Lt. Col. James H. Myers. Trammell told Myers that his company was being cut to pieces. Myers instructed Trammell to withdraw his men and rejoin the battalion at Philippsbourg.

Carrying out this order would first require breaking contact with the Germans—not an easy proposition—regrouping, then taking a circuitous route to Philippsbourg since the main road had been cut.

Trammell said that if he could withdraw his company into Bannstein and occupy the high ground to the rear or south of the town while Myers sent him reinforcements and ammunition he might be able to hold for a while longer.

Communications were then lost with battalion. Shortly afterward, following repeated attempts to contact the 1st and 2nd Platoons and order them to withdraw to Bannstein, Trammell directed 1st Sergeant Bob Holmes to gather everyone in the CP, take the headquarters half-track and jeep, and head south. The captain would remain at the CP and try to establish a defensive line with the available forces in the village. Holmes was also told to guide any reinforcements he came across toward the CP.

At dawn, Sergeant Lillich spotted German tanks and half-tracks coming down the road from the north. Having received no orders, Lillich and the other GIs took it upon themselves to pull back from their positions. Lillich, who was carrying a bazooka, fired three rounds at one of the German tanks. Although he hit the tank, the rockets did no damage. Right after Lillich fired his last rocket, the building which he had been behind was demolished by shellfire.

Back at the company CP, Trammell continued his efforts to contact the 1st and 2nd Platoons. During this time the CP was hit by intermittent mortar shells and small-arms fire.

Though under increasing pressure, the company was still managing to hold out.

It was late morning when Corporal Bernard Flotkoetter, Battery C, 500th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, unexpectedly came through the door of the CP unrolling a spool of telephone wire. The corporal hooked a telephone to it, tested it, and then handed it to Trammell saying there was someone who wanted to talked to him. It was Lt. Col. Dale Swanson, commander of the 500th. Swanson told Trammell that he was placing his battalion in direct support of the captain, that he had his guns ready, and was asking for targets. Also, through the 500th’s switchboard, Trammell could now relay communications back to the battalion.

Acting as artillery forward observer, Trammell placed several concentrations of fire in front of the positions of the 1st and 2nd Platoons. Then he received a call from Staff Sergeant Phipps, who was still at his 1st Platoon outpost. Phipps reported that he was observing a column of German soldiers coming down the road from Eguelshardt. This information, along with map coordinates, was relayed to Swanson, whose artillery then struck the area.

When the action had started, Staff Sergeant Jimmy Long of the 1st Platoon took most of his squad, except Pfc. Frank Caldwell and two other men, into the woods to meet the German assault. Long was killed immediately after entering the forest. As Caldwell and the other two men came forward they ran into their platoon leader, Staff Sergeant Bill J. Bradley, Jr., who ordered them to stay with him.

Bradley had taken charge of the platoon when Lieutenant Warbritton went into a cellar and stayed there, apparently having lost his nerve. Bradley then led the group to a house where eight other members of the platoon were holed up.

As the attack broke over Company C, the 1st Platoon CP was immediately surrounded and cut off. Two squads attempted to break through to the CP but were pinned down. Pfc. Joseph Knapp was hit twice in the stomach by fire from a burp gun, crawled 300 yards to Bannstein, and managed to survive the day.

Near the surrounded CP, the Germans set fire to a building in which one of the Company C men lay wounded. His screams could be heard above the gunfire. Technician Third Grade James T. Hedderman ran through artillery and small-arms fire, rescued the man, and carried him back to the CP, where he received treatment. Hedderman, listed as missing in action afterward, was liberated months later by the 14th Armored Division at the Hammelburg POW camp.

Sergeant John Pleacher managed to get some of the men out of the 1st Platoon CP and infiltrated through the German lines to bring them back to Bannstein. For his actions Pleacher received a battlefield promotion and was awarded the Silver Star.

Just before daylight, Trammell received a call from Bradley asking for instructions. Trammell told Bradley he was going to lay artillery fire and smoke in front of his position so that his men could try to break contact and fall back. But Bradley’s group was unable to break free as German armor and infantry began closing in on the position, forcing them to surrender.

When the 2nd Platoon began to fall back from its position by the lake, the Germans moved in behind them.

Faytak’s squad, 2nd Platoon, had been overrun during the initial attack. Those that could retreated past the villa CP and headed for the woods. As they fell back, Faytak found that every time he fired someone would return fire. Not certain if it was friend or foe, he shouldered his M1 rifle and took a trench knife from his boot as he moved from tree to tree. Anything in white in front of him he struck at since the Germans were the only ones wearing white. Faytak was wounded during an encounter with six or seven Germans and left for dead by his comrades. He was eventually captured and his wounds treated.

In Bannstein, the infantry attacks having been repulsed with the aid of the 500th Armored Field Artillery, a quiet calm settled over Company C, except for an occasional exchange of sniper fire. About noon, though, German tanks entered the north end of the town and began methodically working over the buildings one by one.

While Company C was fighting for its life, task force commander Hudelson tried to organize his few reserves to aid Trammel. The only outfit not yet committed, Company A of the 125th Engineers under Captain Robert Knight, was ordered into action south of Bannstein.

As the engineers moved forward they came across abandoned equipment and bodies.

The lead squad ran into an ambush. Sergeant William Godfrey’s half-track was either hit by a rocket or struck a mine and Godfrey was knocked out. When Godfrey regained consciousness, he found his half-track turned on its side. He had been stripped of his coat and shirt, and his legs were pinned beneath the five-ton vehicle. Around him were four other members of his squad, naked and dead. Next to Godfrey was a GI with a bullet hole between his eyes. Farther up the road he could hear Germans and the sound of digging. Although freezing and in pain from his wounds, he found his trench knife and began digging to free his legs. Once free, he managed to struggle back to his own lines.

After the ambush nearly a third of Company A’s engineers had vanished, and many others were wounded. So much for relief efforts by the engineers.

Trammell called on 1st Lt. Edwin Kosik, with whom he still had contact by phone, and ordered him to pull back through Bannstein. Kosik was to move to the wooded high ground south of Bannstein, bringing all the personnel out of the village with him. Trammell told Kosik that he would join him there.

Because the building that housed the company CP sat apart from most other buildings of the town, and since German troops occupied a house between Trammell and the village proper, he could not move there directly. Trammell also did not want to leave the CP until the last possible minute because there was a chance that the 2nd Platoon might pull back in his direction. He felt he might be needed there to intercept and deploy them. Also, the only means of communications the captain had with higher headquarters and supporting artillery was at the CP. He realized that the moment he left any chance for resupply and reinforcement would also be lost.

Before leaving to join the 3rd Platoon, Trammell made one last attempt to contact the 1st and 2nd Platoons, but to no avail. About this same time a German tank came down the road from the north and began firing at the CP. Just as Trammell left the building the tank fired and blew it up.

The 3rd Platoon, joined by the company’s service and supply personnel along with a few men from the 1st Platoon, destroyed any supplies and equipment they couldn’t carry and moved into the forest south of Bannstein. The 500th Armored Field Artillery laid a barrage behind the retreating men.

The GIs headed for the high ground, then turned southwest while under fire and closely pursued.

Trammell headed for the top of the ridge at the rear of the village, where he had told Kosik he intended to link up with the remnants of the company.

Immediately after Trammell entered the woods, a German machine gun or machine pistol began firing in the area between him and the ridgetop. The captain, therefore, veered off and continued down the road toward the town of Barenthal. By doing this Trammell hoped that he would either be able to rejoin his company farther south, meet the reinforcements he had requested, or find other friendly forces along the way.

When Trammell arrived at the road junction that led to Barenthal, he met up with friendly troops that had been ordered to pick up anyone from Company C and send them to Philippsbourg.

Those elements of Company C that had withdrawn from Bannstein to the southwest fought off continuous attacks. But many of the retreating GIs were cut off and forced to surrender.

One squad of 12 men under Staff Sergeant Phipps, west of the road to Eguelshardt, ran into a German patrol. The Germans looked at the American uniforms but did not react since many Germans had taken American uniforms from dead GIs. Fortunately, Phipps had with him Pfc. Frederick “Pop” Mittlestadt, ammunition bearer for the antitank platoon, whose father had been in the German Army in World War 1 and who spoke impeccable German. Mittlestadt stepped boldly in front of the German patrol and told them in an authoritative voice that Phipps’s squad was on a special mission to go behind American lines and that was the reason for the American uniforms and equipment.

Mittlestadt added that since it was an important mission from the highest authority the German patrol was not to interfere. The Germans responded by letting them pass. Two days later, traveling at night without food and with only snow to quench their thirsts, Phipps and his men returned to friendly lines. For his actions Phipps received the Bronze Star.

Reaching Philippsbourg, Trammell was told to assemble the remnants of his company at the village of Zinswiller, about 10 kilometers farther south.

For nearly 12 hours the GIs of Company C, 62nd Armored Infantry Battalion, held up the advance of troops of the 953rd and 951st Volksgrenadier Regiments, preventing a German breakthrough.

Five days later, the morning report for January 6, 1945, showed the strength of Company C as four officers and 139 men. Two officers and 71 men were reported as missing. Despite these losses, in two weeks’ time the company would be committed to one of the 14th Armored Division’s fiercest actions of the war at Hatten-Rittershoffen.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments