By Vince Hawkins

In 1490 Japan entered a crucial period of its history known as the sengoku-jidai, or the “Age of the Country at War.” For the next century and a half, scarcely a year would pass without a battle or a campaign ragingsomewhere in the country. The daimyo, or “great names” (erroneously referred to as “warlords”), who controlled the numerous provinces of Japan, began to vie with one another to increase their domains and the power of their family clans. For a few—those who had the military power and the political strength to challenge—it was a chance to become Shogun, the military ruler of Japan.

By the middle of the 16th century, warfare in Japan significantly changed, influenced to a great extent by the ever-increasing struggle between the competing daimyo. The samurai (meaning “those who serve”) armies of the daimyo began to increase in size, augmented by the addition of the ashigaru (or “light-feet”), trained, well-disciplined peasant foot soldiers. Castles began to take on a greater military prominence as a means of controlling an area and as a secure base for military supplies and troops. Lastly, an invention from Europe, the firearm, began to appear in samurai armies beginning in 1540.

The power of the daimyo, and thus the power of his clan, stemmed from the territories or provinces he controlled. Their economic wealth was measured by the agricultural production of their lands and was assessed in koku. A koku was the amount of rice it took to feed one man for one year. koku provided the system of measuring the yearly yield of the rice fields and also determined the number of soldiers the daimyo could raise, arm, and feed to defend his lands. From these lands also came the men who would form the daimyo’s army. The samurai, essentially hereditary vassals and retainers of the lord and his clan, were expected to raise and equip a predetermined number of troops from the clan domains they controlled. These would include other samurai of lesser rank as well as the ashigaru. When the daimyo’s army conquered another province or territory, his loyal samurai could expect an increase in their domains, which would in turn increase their personal wealth and the number of men they would now be expected to raise from that domain. The conquest of another territory also meant that a daimyo could increase his wealth and military strength by either making the conquered lord a vassal, thus securing his army and his wealth, or by striking an alliance with the conquered lord for his support in future military operations. Under such a system it is understandable why the daimyo became so fiercely engaged in territorial expansion. One of the more interesting examples of such territorial warfare was between the daimyo of the Echigo and Kai Provinces.

An Intense Rivalry Forms Between Clans

In 1553 an intense power struggle began between the Takeda clan of Kai Province, under the leadership of Takeda Shingen, and the Murakami and Nagao clans of Echigo Province, under Uesugi Kenshin. This conflict resulted in a long-standing military rivalry between these two daimyo that lasted until 1564. In 1547 Shingen led the Takeda clan on an invasion of Shinano Province, a rich territory that lay between the western border of Kai and the southern border of Echigo Province. In lieu of being destroyed by the powerful Takeda army, some of the Shinano daimyo, such as the Sanada, submitted to the invader and became Shingen’s vassals. Many of the other Shinano daimyo were determined to resist the invaders, the most noted of these being Murakami Yoshikiyo. In 1548 Shingen defeated Murakami in a bloody battle at Ueda-hara. Realizing that he could not withstand Shingen’s power alone, Murakami appealed for aid from his northern neighbor, Uesugi Kenshin, Lord of Echigo Province. Kenshin agreed to give his assistance to Murakami, and with this alliance the two powerful clans of Takeda and Uesugi were brought into direct conflict.

In assembling the army to aid Murakami, Kenshin sent out the kashindan, or “call to arms.” This, it seems, was usually in the form of a detailed letter, sent to all the loyal retainers of the clan. Among the reasons given for calling out the army, there would also be included a listing of their record of obligations, such as the number of troops by type they were to provide, the arms and supplies, and where they were to concentrate their forces. A good example of a surviving kashindan, written by Uesugi Kenshin to Irobe Katsunaga, his gunbugyo, or “chief of staff,” follows, and aptly describes the situation brought on by Shingen’s invasion of Shinano Province.

“I, Kagetora, Will Set Out For War and Meet Him Halfway”

“Concerning the disturbances among the various families of Shinano and the Takeda of Kai in the year before last, it is the honorable opinion of Imagawa Yoshimoto of Sumpu that things must have calmed down. However, since this time, Takeda Harunobu’s [Takeda Shingen’s previous name] example of government has been corrupt and bad. However, through the will of the gods and from the kind offices of Yoshimoto, I, Kagetora [Kenshin’s previous name] have very patiently avoided any interference. Now, Harunobu has recently set out for war and it is a fact that he has torn to pieces the retainers of the Ochiai family of Shinano and Katsurayama castle has fallen. Accordingly, he has moved into the so-called Shimazu and Ogura territories for the time being…. My army will be turned in this direction and I, Kagetora, will set out for war and meet him half way. In spite of snowstorms or any sort of difficulty we will set out for war by day or night. I have waited fervently. If our family’s allies in Shinano can be destroyed then even the passes of Echigo will not be safe. Now that things have come to such a pass, assemble your pre-eminent army and be diligent in loyalty, there is honorable work to be done at this time.

With respects, Kenshin, 1557, 2nd month, 16th day.”

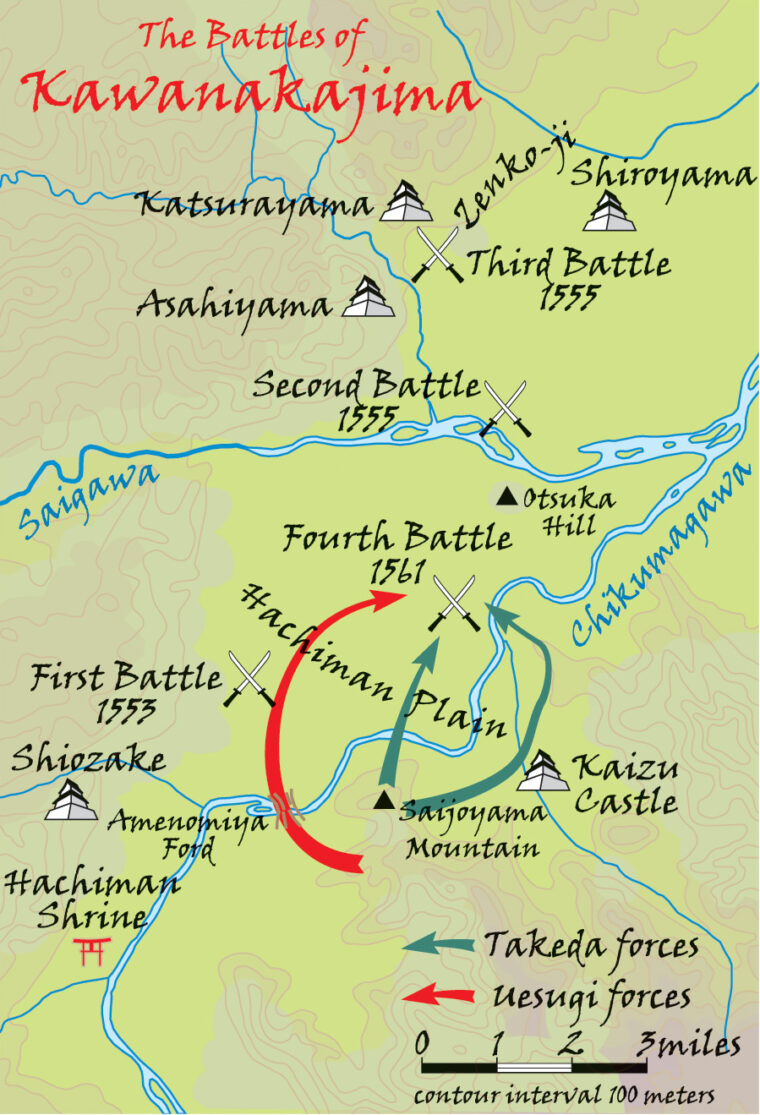

In the far northern reaches of Shinano Province, located deep in the heart of the mountain range known as the Japan Alps, lay the wide, flat, triangle-shaped plain of Kawanakajima. Known as “the island between the rivers,” because it was bordered on the north by the Saigawa River and on the southwest by the Chikumagawa River which join at the northeast corner of the plain, Kawanakajima became the “no man’s land” in the duel between Shingen and Kenshin. During the course of their struggle this plain would witness no less than seven encounters between these rivals, of which only five were considered “battles.” The first three of these battles were only preliminary skirmishes compared to the fourth, which is considered the Battle of Kawanakajima, and remains one of the largest and bloodiest conflicts in Japanese history.

Kawanakajima’s Series of Bloody Battles

In September 1553, Shingen advanced far to the north of Shinano Province, reaching the Kawanakajima plain. Here, near a Hachiman shrine, he met Kenshin’s army, but refused battle and withdrew. The two armies came into contact a few miles farther north, but again disengaged from each other. This was the “First Battle of Kawanakajima,” also known as “The Battle of Fuse.” In October, as Shingen was withdrawing from the area, Kenshin attacked near the site of the Hachiman shrine and defeated the Takeda army.

The “Second Battle of Kawanakajima,” also known as “The Battle of the Saigawa,” took place in 1555. Shingen advanced across the Kawanakajima plain to the Saigawa River and made his camp on the Otsuka hill, just south of the river. Kenshin’s army moved from their hill positions down to the river and camped on the opposite bank. For four months the two armies sat facing one another, each waiting for the other to make the first move. Eventually, faced with political unrest among their allies, both armies withdrew.

The “Third Battle of Kawanakajima” took place in 1557. Shingen again advanced onto the plain and captured Katsurayama, a mountain fortress deep in Uesugi territory. He then attacked Iiyama Castle, which lay along a major road into Echigo and northeast of the Zenko-ji, a hilltop position with a dominant view of the entire plain. Kenshin, whose army was based in Zenko-ji Castle, responded by launching a sortie to relieve Iiyama Castle. Shingen promptly withdrew, once again avoiding a major battle with his enemy.

In September 1561, the two armies engaged in the “Fourth Battle of Kawanakajima.” Kenshin, weary of the sparring with Shingen, resolved to destroy his archrival in one last decisive battle, and marched his army of 18,000 toward the northwestern periphery of Takeda territory. His objective was Kaizu Castle, which controlled Takeda communications north onto the plain of Kawanakajima and south of the plain through the vital mountain passes. Crossing the Saigawa and Chikumagawa Rivers, which enclose Kawanakajima, Kenshin took up a fortified position on Saijoyama Mountain overlooking Kaizu Castle. The 150 samurai and their followers who garrisoned Kaizu, although thoroughly surprised by this move, managed, through a system of well-organized signal fires, to alert Shingen of the danger. Shingen reacted quickly and moved toward Kaizu with 16,000 men.

Operation “Woodpecker”

Shingen camped on the west bank of the Chikumagawa River near the Amenomiya ford. Kenshin had hoped to be in a position to fall on his enemy upon the latter’s arrival, but with the river between them a stalemate ensued. An element of surprise was needed to throw one side off balance if the other were to succeed. Shingen moved first, quickly crossing the Chikumagawa beneath Kenshin’s positions and moving his entire force, increased by reinforcements to 20,000, into Kaizu Castle.

Shingen’s force would not remain there long, however, because his gunbugyo,Yamamoto Kansuke, had devised an interesting plan known as Operation “Woodpecker.” A “woodpecker” force of 8,000 men would climb Saijoyama under cover of night and “tap” Kenshin’s rear, driving the enemy “bugs” out of their positions, down the mountain, and across the Chikumagawa onto the Hachimanabara, or “War God Plain,” below. Here, Shingen’s main body, having also crossed the Chikumagawa by night, would be waiting for them. The formation Shingen chose for his main body was the kakuyoku, or “crane’s wing,” which was considered to be the best formation for surrounding an enemy. Driven by the attack against his rear into the arms of the “crane’s wing,” Kenshin would be caught between two forces, surrounded, and destroyed.

According to Stephen Turnbull in Battles of the Samurai, the crane’s wing formation was deployed as follows: “A screen of arquebusiers and archers protect the vanguard while the main body of samurai, forming a second and third division, are spread out behind them like the swept-back wings of a crane. The general’s headquarters occupy the center, protected on both sides by hatamoto (meaning “under the standard”), the particular chosen samurai. A squadron of reserve troops stands on each side, slightly to the rear of the hatamoto. There is a rear guard, with more archers and arquebusiers.”

Shingen set up his headquarters in the center of the Hachiman Plain, somewhere in the rear of the samurai wings. This command post consisted of a maku, or cloth curtains, bearing the Takeda mon, or clan badge, making it easily identifiable to all. From this position he waited for his plan to be put into motion.

Kenshin’s “Winding Wheel” vs. Shingen’s “Crane”

As dawn broke the next day Shingen’s troops, peering through the dispersing mist, were met by the sight of Kenshin’s army not fleeing across their front, as planned, but charging head on toward them. Kenshin, having received reports on Shingen’s movements, had guessed what his rival’s plan might be and had accordingly planned a countermaneuver. Using the cover of night as had his enemy, Kenshin had moved his army in total secrecy across the Amenomiya Ford, leaving a 3,000-man rear guard to protect the ford, and deployed somewhat west of Shingen’s position.

Adopting a formation known as kuruma gakari, or “winding wheel,” Kenshin crashed violently into Shingen’s “crane.” The winding wheel was an offensive maneuver allowing units that had become exhausted or depleted to be replaced with a fresh unit, thus enabling the attacker to maintain the force and momentum of the attack. A very carefully organized and complex maneuver, its use indicates that Kenshin’s troops must have practiced it to the point of perfection. Kenshin’s vanguard was commanded by his younger brother, Takeda Nobushige, and as Kenshin’s winding wheel fully engaged the Takeda front ranks, Nobushige was killed in the desperate close combat.

Kenshin’s leading units were mounted samurai, and as the “wheel” wound on, the pressure on Shingen’s force began to tell as unit after unit was driven back from its position. Shingen’s “crane” was an offensive formation and not designed for the defense, but the troops executing it were well disciplined and the formation was managing to hold its own. Realizing that his well-laid plans had failed, Yamamoto Kansuke accepted responsibility for the disaster in true samurai fashion. Charging alone with a spear into the midst of the enemy he fought valiantly until overcome by some 80 wounds, whereupon he retired to a grassy knoll and committed hara-kiri (ritual suicide).

The momentum of the “wheel” had by now brought it within reach of the Takeda headquarters where Shingen had been fervently trying to control his hard-pressed army. The Uesugi samurai clashed head on with Shingen’s hatamoto and personal bodyguard, wounding his son Takeda Yoshinobu. A single, mounted samurai then crashed through the maku curtains and Shingen suddenly found himself personally attacked by none other than Kenshin himself. Unable to draw his sword in time, Shingen, rising from his camp stool, was forced to parry Kenshin’s mounted sword strokes with his heavy wooden war fan. Shingen took three cuts on his body armor and a further seven on his war fan until one of his bodyguards charged forward and attacked Kenshin with a spear. The spear thrust glanced off Kenshin’s armor and struck his horse’s flank, causing the animal to rear. Several other samurai of Shingen’s guard then arrived and together they managed to drive Kenshin off. (In Battles of the Samurai, Turnbull says, “The site of this famous skirmish is now called mitachi nana tachi no ato [‘three sword seven sword place’], and next to it is a fine modern statue depicting the fight between the two generals.”

25,000 Combined Casualties; A Costly Battle

Shingen’s “crane” was slowly being driven back on the Chikumagawa River and his best samurai were falling all around, but despite the fierceness of the constantly rotating attacks the formation had not yet broken. Just as Kenshin seemed assured of victory he was suddenly surprised by a desperate attack against his rear. The Takeda “woodpecker” force, having found the enemy positions on Saijoyama deserted and hearing the noise of battle below, had moved down to the Amenomiya Ford. Here they engaged Kenshin’s rear guard in the fiercest fighting of the day, driving them back and crossing the river to assault Kenshin’s rear. Kenshin’s force was thus caught between the pincers of the Takeda attack, just as the late Yamamoto Kansuke had planned. Shingen managed to regain control of his army and by midday what had seemed an inglorious defeat had been turned into a great victory. Some of Shingen’s troops even managed to reclaim the head of Nobushige, Shingen’s brother, as well as the heads of several other leading Takeda samurai from the Uesugi warriors who had taken them as trophies. Shingen’s army, exhausted from the battle, did not attempt to pursue Kenshin’s retreat. The following day, under a truce, some of Kenshin’s generals burned what was left of their encampment on Saijoyama while the rest of the army moved back across the Saigawa and headed for home.

Kawanakajima had been a costly battle for both sides. Kenshin had lost 72 percent, or roughly 12,960 men, while Shingen, although taking 3,117 enemy heads as trophies, had lost 62 percent, or 12,400 men. In one of the largest battles ever fought in Japanese history, the “crane’s wing” formation, when executed by well-disciplined troops, had proven itself capable of stopping, at least temporarily, that of the “winding wheel.”

The Final Battle Between Deadly Rivals

In September 1564 the two rivals met again for the fifth and final battle at Kawanakajima. Facing each other across the Saigawa River the respective armies sat in their positions for 60 days, engaging in only minor skirmishing, before finally withdrawing.

The battles at Kawanakajima stand as a fascinating example of the style of clan warfare that typified the sengoku-jidai period as well as the type of highly ornate and complicated tactics employed by the armies. The ability to perform complex maneuvers by night and then assemble into such large and intricately designed tactical formations speaks volumes for the high degree of training, discipline, and weapons specialization clearly evidenced by the armies of the daimyo. Incidentally, a good and fairly historic example of the battles of Kawanakajima, the rivalry between Shingen and Kenshin, and the tactics employed by the armies can be seen in the Japanese film production Heaven and Earth.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments