By Michael Kluever

The medieval polearm was the Colt Pistol equalizer of the Middle Ages. it placed the common infantry soldier on par with the heavily armored horseman. The polearm forever ended cavalry’s thousand-year domination of the battlefields of Europe.

With the exception of the spear, most polearms can trace their ancestry back to contemporary agricultural tools.

The bill, fauchard, and glaive are close cousins of tree trimmers. Offspring of the woodsman axe are the halberd, poleaxe, and vogue. The military fork and war scythe needed little if any changes from common farm tools to make them devastating weapons.

Unlike the Colt, the varieties of polearm designs were endless. Man’s ingenuity to devise grotesque instruments of killing is amply illustrated with these unique and diverse types of medieval weapons. Each mutation had a specific killing purpose.

Polearms comprise weapons of which the killing instrument is mounted on a wooden (occasionally, even an iron) shaft. They can be divided into three broad classes. The first comprises thrusting and stabbing instruments such as spears and pikes. The second comprises weapons for cutting and slashing, such as the poleaxe and lochaber axe. Third are more versatile types combining the best features of thrusting and stabbing with those of cutting and slashing, such as the halberd, glaive, and bill.

Polearms served two distinct functions. Foremost, they were fighting weapons. These were generally heavy and relatively easily made, frequently the work of blacksmiths or lesser armorers. Many possessed two or more long steel straps (cheeks or languets) of two feet or more connecting the head to the shaft. These not only fixed the head firmly to the shaft, but also prevented the head from being severed from the pole by axe or sword.

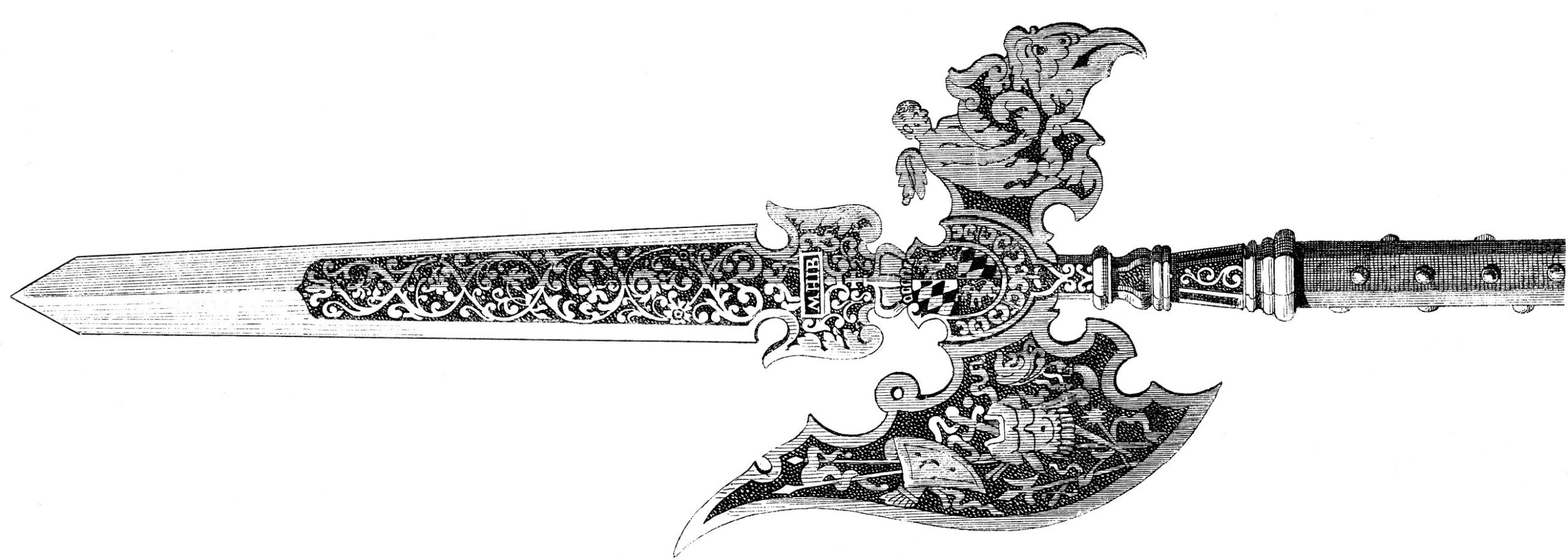

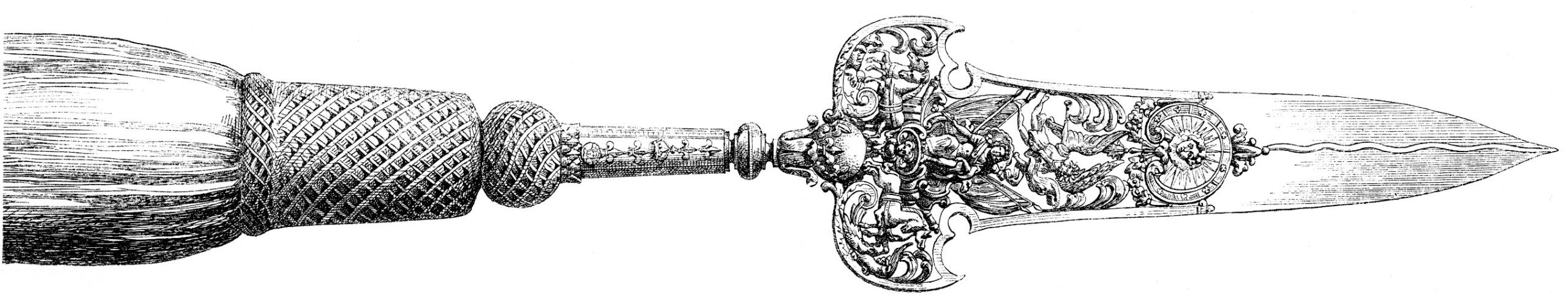

But polearms also served as parade pieces. These were elaborately decorated with fine engraving or pattern cutouts on the blade. Some were further highlighted in silver or gold. These were given to elite units, usually those assigned to protect important personages. Even today, the Vatican Guards and the Tower of London Beefeaters carry such weapons.

One of the difficulties in identifying and classifying polearms lies in each modification, however slight, being given its own name. The glaive, fauchard, and bill resemble one another but hold subtle differences. To complicate nomenclature further, some shafted weapons are known by more than one name. The ranseur is also known as the runka and the rawcon. Listed here are the main types of polearm.

Spear. The earliest and most identifiable polearm is the spear. Dating to antiquity, the spear, whether possessing a stone, bronze, or iron head, was principally a throwing weapon. From the 12th through the 14th centuries the head was generally a simple leaf or was lozenge shaped. During the 14th century the triangular shape was the most popular. Sickle-shaped wings at the base of the blade were common during the 15th through the 16th centuries (this limited penetration, thus allowing for quick removal).

A light throwing spear was a favorite of light infantry for harassing enemy front lines immediately before an attack. Those called darts or javelins had smaller heads and shorter shafts. Heads were sometimes barbed to make removal more difficult. Removing the barbed head further increased the size of the wound and the opportunity for infection. For greater accuracy, feathers were added, giving the weapon the appearance of a giant arrow.

Lance. The medieval lance was the horseman’s spear. Along with the sword, it was the primary offensive weapon of the mounted knight. The 14-foot or longer shafts were composed of ash, cypress, aspen, or pine and terminated with a socketed spearhead. Unfortunately, the lance was difficult to control on impact—the rider was driven backward. This was partially solved by the 14th century with the addition of a rondel, a small, thick, leather disc-shaped stop over the lance’s shaft behind the hand. Resting against the armpit, it absorbed some of the shock previously borne by the arm alone. Further refinement during the 15th century was the addition of a bracket across the knight’s breastplate—it acted as a lance stop.

Pike. The most widely used of all medieval shafted weapons was the pike. Its primary task was to keep cavalry at a distance. The steel head was mounted to a 16- to 20-foot shaft. A metal point (ferrule) attached to the end of the shaft allowed for ease in planting the pike into the ground. Grasped by two hands widely extended and angled toward advancing horse, pikes made an impenetrable hedgehog of bristling points when presented by three or more ranks. They were used to protect archers, musketeers, and infantry.

All European armies used the pike extensively. In 1425, 38 percent of the Swiss Federation of Lucerne consisted of pikemen. Similar percentages were present in the armies of the Thirty Years War.

Awl Pike (Ahlspiess). The ahlspiess was a Germanic thrusting spear used during the 15th and early 16th centuries. Its head consisted of a very long (sometimes 50 inches or more) quadrangular-shaped spike with a rondel (round metal disc) at its base to protect the hands. In France similar weapons were termed “lance a pousser” and in England “awl pike.”

Bill. Derived from the agricultural implement of the same name, the bill was a most popular weapon. Its head consisted of a broad, single cutting head with a hook or spike protruding from its back, usually toward the blade’s point. A favorite of the English, it saw extensive use on the Continent and with early North American settlers. It has been called the English halberd. However, unlike the halberd, the bill’s lighter head was less effective against armor. Its spear and beak could be effective against mail, but failed at penetrating plate. Fifteenth-century Turks also made use of this weapon.

Bohemian Earspoon. The bohemian earspoon’s long spearlike head, often exceeding two feet in length, possessed two small triangular projections at its base. The long blade discouraged cavalry from attacking, while the projections allowed for quick withdrawal and were equally effective at parrying counterblows. This weapon was especially popular during the 15th century.

Corseque. The corseque (sometimes referred to as the korseke) is truly an evil-looking weapon. Its unique head consists of a single, long triangular blade with two wide but shorter triangular crescent-shaped blades whose points curve toward the longer blade. The side blades could be used in conjunction with the central blade to fend off an enemy. The corseque could also unhorse a rider. Possessing the appearance of a maple leaf, it was favored in France and Italy from the second half of the 15th until the early 17th century.

Fauchard. A member of the glaive family, this 16th-century polearm has a long, broad, single-edged curved blade with ornamental prong or prongs on its backside. Possessing the capability to thrust as well as cut, it saw service primarily in France, southern Italy, and Germany.

Military Fork. Like many medieval polearms, the military fork’s origins lie with an agricultural implement of the same name. In fact, this farm tool required no modification to become a highly effective military weapon. The military fork is recorded to be in use as early as the 12th century and continued in use into the 18th. By the 14th century military forks were expressly designed for warfare. These consisted of a straight fork with the tines widened into cutting blades. Some possessed as many as three prongs. Others carried a small halberdlike head just below the fork. A special siege variant had two downward hooks added for grappling siege ladders rungs, tops of fortified walls and, of course, unlucky defenders on those walls. Peasants of the period frequently utilized forks during their numerous uprisings.

Glaive. The glaive was a simple, long, broad-bladed weapon with a false backward curved edge near the top. In appearance, it is little more than a sword blade mounted on a shaft. First encountered during the 13th century, it was popular in all parts of Europe during the Middle Ages. Favored more on the Continent than in Britain, it also found favor with the Chinese (at a later date); the Japanese produced a version called a naginata.

Guisarme. The simple (and cheap) construction of the guisarme made it a popular infantry weapon in Europe from the 11th through the 15th centuries. A member of the bill family, its head consisted of a long lethal blade with an elongated hook running parallel with the blade. The hook’s purpose was to yank a rider from his horse.

Halberd. Perhaps the most effective of medieval shafted weapons, and certainly the most feared, was the halberd. It could do it all. Mounted on an eight-foot or longer shaft, its head consisted of a heavy lethal axe with a hook or beak opposite. A long spearlike spike protruded from its top. The halberd was the national weapon of the Swiss during their fight for independence. The spear discouraged cavalry and infantry alike. A single swing by strong arms had its axe cleave the finest helmets, shields, and armor or cut an unarmored infantryman in half. The hook was capable of pulling knights from their steeds and could also be utilized as a can opener in a knight’s armored joints. A tassel near the top of the pole kept moisture from running down the shaft. Long steel strips (langets), part of the head and fastened down the shaft, reinforced the head and prevented cutting.

The halberd remained a favorite of European infantry from the 13th century until improvements in firearms made it obsolete. Even thereafter it served as a parade weapon with highly ornate pieces produced by master armorers for elite units. The Vatican Guard still carries this weapon.

Lochaber Axe. While the Lochaber axe has the appearance of a poleaxe, it is actually a descendant of the guisarme family. The broad cleaverlike blade had a convex cutting edge often projecting beyond the top of the shaft and terminating in an acute point. A hook, usually forged to the back of the blade or fastened to the top of the shaft, proved useful in catching mounted warriors and scaling walls (it could also be used to hang the weapon when not in use). Used almost exclusively in Scotland during the 16th through the 18th centuries, it was capable of cleaving in half a lightly armed warrior.

Lucerne Hammer. Created in Switzerland during the early 15th century, the Lucerne hammer was a favorite of the canton levies. It proved an especially effective weapon for fighting among the lists. It was rare in other European armies where it might be called marteau, bec-de-corbin or bec-de-faucon. This is a rather unique weapon. Its head consisted of a hammerhead with four projecting prongs and a single beak opposite. The shorter prongs were designed to crush armor, the longer points for use against lightly armored troops. A long triangular spike at the top served to discourage cavalry.

Ox Tongue, Lange De Boeuf. The ox tongue resembled the tongue of the ox. A broad, straight double-edged blade of either a square or triangular shape tapered to a point. An ox tongue proved easy to make and simple to use. Much employed throughout Europe during the 16th century, its prime purpose was to defend against cavalry attacks, its broad blade producing ghastly wounds upon horse and rider.

Partizan, Partisan. Originating in Italy, the partisan resembled the pike except that it was wider and longer. The blade had curved metal branches arching toward the point at the base of the head. Used throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, it was frequently carried by guards of dignitaries. Elaborately engraved, they were the works of master armorers. A smaller version of the partisan is the spontoon, carried by noncommissioned officers during the 18th century and used to direct movements.

Poleaxe. The poleaxe is nothing more than a large bladed fighting axe mounted to a shaft five to six feet long. It could produce hideous wounds. Armor was not immune to its blows. The downside was that, as a two-handed weapon, the wielder was unable to protect himself with a shield.

Ranseur, Runka, Rawcon. This 15th- and 16th-century polearm had a narrow center blade flanked on each side by two short lateral blades. It closely resembled the corseque, except that the lateral blade was less pronounced.

War Scythe. The war scythe is nothing more than an agricultural implement of the same name mounted vertically on a wooden shaft. Most of these were crudely made blacksmith productions. With little or no modifications, scythes proved a popular peasant weapon during the Middle Ages.

Spetum. This 16th-century polearm is among the least known. Its long narrow blade had two sickle-shaped projections at its base curving back toward the user. The weapon was equally adept at keeping cavalry at bay and yanking those adventurous riders who strayed too far away from their horses. Its use was generally confined to southern Europe, being widely used in Italy.

Vogue, Vougle. The head of the vogue is composed of a broad axe with a spike opposite. Its head had two eye sockets for holding the shaft firmly in place. It was a favorite of the Swiss mercenaries, but versions were found elsewhere as well. Some consider the vogue the grandfather of the halberd.

There are hundreds of variations of these basic types, each with its own local name and designed purpose. This is hardly surprising owing to the fact that local blacksmiths made many of the polearms and converted others from agricultural implements. Because of the sheer numbers produced during the Middle Ages, some have survived and can be found in museums and private collections and are occasionally available through dealers or at auctions.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments