By Mike Haskew

During the September 17, 1862 Battle of Antietam, casualties piled almost too high to count. The culmination of the first invasion of the North during the American Civil War by General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, it was the bloodiest single day in the history of the United States and the bloodiest day’s fighting ever in the Western Hemisphere. Due to the massive scale of the losses, the Antietam death toll has always been hard to accurately determine.

The Battle of Antietam’s Three Phases

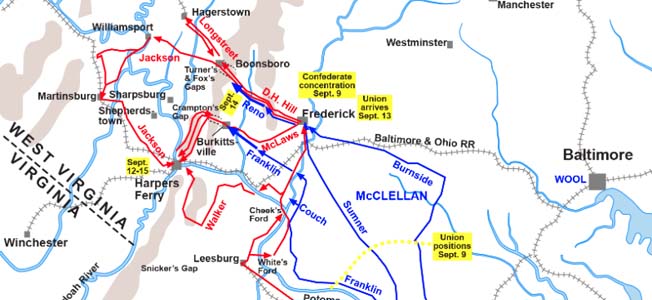

The Battle of Antietam swirled in three phases from north to south and lasted from early morning until dusk. During the first phase, fighting raged in a 24-acre cornfield and on high ground surrounding the Dunker Church, which belonged to the German Baptist Brethren, a Christian sect that believed in baptism by full immersion and were, therefore, known as “Dunkers.” Casualties were extremely heavy in the Cornfield, with some regiments suffering greater than 70 percent casualties. At midday, the fighting had shifted to a sunken road that formed a natural trench-like defensive position. Confederate troops shot down rank after rank of attacking Union troops from the sunken road, later to be called Bloody Lane, until their position was flanked and the depression became a deathtrap. Confederate bodies were strewn so thickly through Bloody Lane by the end of the day that it was impossible to take a step without touching a corpse.

Late in the afternoon, Union troops finally succeeded in crossing a stone bridge over Antietam Creek and moving up the slope on the stream’s western bank. Although they left scores of dead and wounded in their wake, the Union troops pressed on toward the town of Sharpsburg, Maryland, and were poised to trap Lee’s army against the Potomac River. However, the timely arrival of A.P. Hill’s Light Division from Harpers Ferry, 12 miles away, blunted the Union drive and ended the battle.

Night Might Never Come

One veteran of the fighting at the Battle of Antietam remembered that the sun seemed to pause high in the sky and it felt as if night would never come. The ferocity of the battle is reflected in the appalling casualties suffered by both sides. Nearly 23,000 men were killed and wounded, with more than 1,500 Confederate dead and over 2,100 Union soldiers slain. Six generals either died on the field or succumbed to wounds suffered at Antietam, including Union Major Generals Joseph K.F. Mansfield and Israel Richardson and Brigadier General Isaac Rodman, and Confederate Brigadier Generals Lawrence O. Branch, William E. Starke, and George B. Anderson.

Before the dead were buried, photographer Alexander Gardner and his assistant James Gibson, employed by the famed Mathew Brady, traveled to the battlefield and recorded a series of images depicting with stark clarity the horror of war. In many of Gardner’s photographs, the dead lay where they fell, their bodies in grotesquely contorted positions, frozen before his lens. Many of the images were displayed in Brady’s New York gallery, and the exhibition was billed as “The Dead of Antietam.” The death studies stunned the public and emphasized that the cost of the war would be substantial.

Buried Hastily in Shallow Graves

So many soldiers of both sides died during the Battle of Antietam; casualties were sometimes buried hastily in shallow graves and never moved to formal cemeteries. As recently as 2009, the remains of soldiers who were interred on the field, their final resting places forgotten, have been rediscovered. Although it is most often impossible to specifically identify the remains, one soldier was determined to have been from a New York regiment that fought in the cornfield. His name will never be known; however, the buttons of his jacket identified his home state. The remains were accorded full military honors and returned to a New York cemetery for burial.

A horrible waste of life,a lot of Irish immigrants died on them battle fields eg the 69th.

James Kennedy Co.D, 69th regt. Pa. Vol wounded at Antietam the original fighting Irish. Great losses on both sides. We need to remember our history, and legacy and learn valuable lessons from it.

Who was this written by and when was this published?

My great/great grandfather and his brother were there as part of the 1st Texas Regiment. He was wounded in the cornfield counter attack early that morning. He convalesced in Richmond in time fight in the Devil’s Den @ Gettysburg.

I am trying to locate my third great-granduncle, Henry Swisher Rutherford.

I found a few records saying he was in this war.

That same record states he was wounded on 17 Sep 1862.

Can anyone help me in this matter?