by William E. Welsh

Dawn on July 1, 1862, ushered in a hot summer day. After having assumed the offensive five days earlier, General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army seemed to have at last cornered his adversary’s mighty Union host at Malvern Hill overlooking the James River.

Despite almost daily fighting, Lee’s army had failed to crush Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s army as it limped away from Richmond. After inconclusive fighting in the Battle of Glendale fought the previous day, the Confederates believed that at last the Federal army was demoralized, and therefore ripe for defeat.

[text_ad]

Not all of the Confederate generals were convinced that the Yankees were as good as beaten. When Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill met up with Lee and Maj. Gen. James Longstreet on the Willis Church Road, he shared advice received from a local guide regarding the strength of Malvern Hill. “If General McClellan is there in strength, we had better let him alone,” warned the North Carolinian. The man who would go on to become one of Lee’s corps commanders was quick to dismiss the warning. “Don’t get scared now that we have got him whipped,” said Longstreet.

Confederate Shortcomings Led to Disaster at Malvern Hill

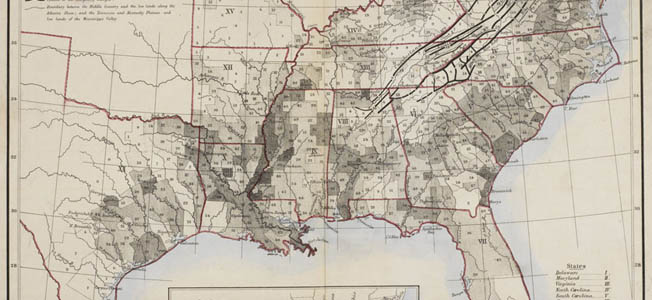

There was a lot of truth to Hill’s battlefield intelligence. The Army of the Potomac’s position on Malvern Hill was anchored by cliffs on the west and a swamp on the right. As if that was not enough, Lee’s army had functioned poorly during his offensive thrusts over the past several days. His engineers had not mapped the ground and the generals knew little of the road network. In addition, poor communications between divisions and the uncharacteristically lethargic performance of Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, had allowed Union forces more than once to escape clever traps that Lee had laid.

Lee allowed some of his forces, those who had borne the brunt of the fighting at Glendale, to serve as the reserve on July 1. On the Confederate right, Lee entrusted the opening attack to Maj. Gen. John Magruder supported by Maj. Gen. Benjamin Huger. On the Confederate left, Harvey Hill and Jackson were to assail the Federal position.

With McClellan preoccupied with establishing a new base on the James River, the defense of Malvern Hill was entrusted to Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter, the competent V Corps commander. Porter deployed his corps on the Union left, opposite Magruder and Huger, and the Union IV Corps, backed by the III Corps, on the Union right opposite Hill and Jackson. To put teeth into his defensive position, Porter and his artillery chief, Colonel Henry Hunt, deployed six batteries facing north to repel a Confederate frontal attack.

Confederate Grand Batteries Fail to Soften Union Position

The gray columns wound their way toward Malvern Hill throughout the morning. When Lee surveyed the Federal position, he ordered two grand batteries established, one for each wing of the army. It was their job to bring converging fire against the Federal guns destroying as many of them as possible before the gray tide swept forward. The Confederate artillery bombardment was a disaster. Because of the superiority of the Union rifled guns, and because they held the higher ground, they drove off the guns of both Confederate grand batteries.

Harvey Hill, for one, was convinced that there would be no attack. He and his brigadiers were preparing to bivouac for the night when a signal was given by Magruder’s forces indicating an attack was underway. Ominously, Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead’s brigade leading off Magruder’s attack at 4 PM was pinned down in a wrinkle of the landscape almost as soon as it advanced. The signal for a general assault ought never to have been given.

The Federal guns swept every corner of the 400 yards over which the gray infantry charged up the hill. Magruder’s piecemeal attacks were quickly shattered. In the center, Harvey Hill’s 8,000 men in five brigades did their best to reach the Federal guns. At one point a shell exploded next to Hill shredding his uniform but sparing him serious injury. The brave commander of a brigade of Alabamians, Colonel John B. Gordon, got to within 200 yards. Gordon and Hill’s other brigadiers sent desperate requests by messenger back to Hill for reinforcements. Hill combed the woods for fresh units to feed into the battle. Finding a brigade of Georgians that belonged to Magruder’s command that had strayed into his sector, Hill directed them into battle himself. Jackson, observing the catastrophe that befell Hill’s division, restrained his subordinates from leading their troops into battle.

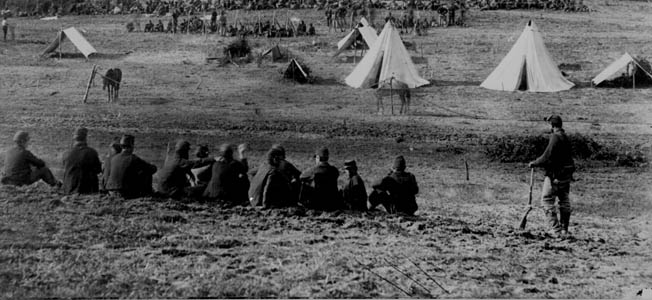

The fighting lasted between for about five hours. Those Confederate units pinned down on the hillside withdrew under cover of darkness. “The enemy mowed us down by the fifties,” said William Calder of the 2nd North Carolina, who participated in the assault that day. “It was not war—it was murder,” said Hill.

Visitor Center Located at Site of Confederacy’s Greatest Iron Works

Malvern Hill battlefield today is preserved as part of the National Park Service’s Richmond National Battlefield Park. The park comprises the most significant battles of the so-called Seven Days Battle of 1862 in which Lee drove McClellan away from the gates of Richmond, including Beaver Dam Creek, Gaines’ Mill, Glendale, and Malvern Hill.

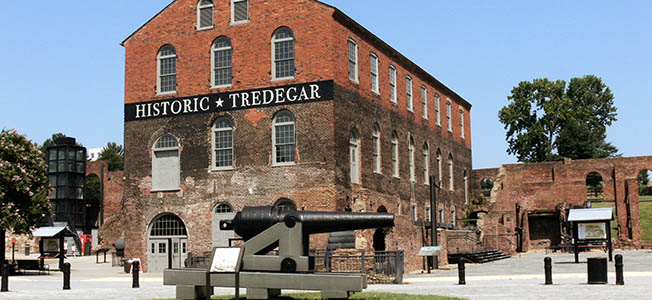

The main site for information about both the 1862 Seven Days Battle and for sites associated with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s 1864 Overland Campaign is the visitor center in downtown Richmond at 470 Tredegar Street. The visitor center is located on the site of the Tredegar Iron Works, which was the Confederacy’s principal iron foundry in support of the Southern war effort. The five-acre foundry and rolling mill produced 1,100 cannon for the South.

The visitor center offers a short orientation film, exhibits, and information on living history programs. Rangers and volunteers working at the center help guests tailor their visits to their individual needs and answer questions about the Richmond battles and sites.

Hood’s Texans Breached Union Lines at Gaines’ Mill

For the 1862 campaign, a clockwise driving tour first takes visitors to Beaver Dam Creek, where Lee attacked a wing of the Federal army north of the Chickahominy River. It proceeds to Gaines’ Mill where the right wing of the Union army withstood a day-long assault by Lee’s army. At dusk Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood’s crack Texas brigade spearheaded a desperate assault that breached Porter’s position and compelled him to withdraw across the Chickahominy.

The final stop covers the battlefields of Glendale and Malvern Hill. A seasonal visitor center located at 8301 Willis Church Road furnishes orientation to the Seven Days Battle and offers ranger-led tours.

Another key site associated with the 1862 campaign is Drewry’s Bluff, south of Richmond, where guns mounted at a Confederate fort blocked an attempt by Union gunboats on May 15, 1862, to get far enough up the James River to shell the Confederate capital.

TIP: The Richmond National Battlefield Park is composed of 10 units of park property, as well as some other ancillary sites. To see everything requires more than one day. The park service recommends four must-see sites for visitors with limited time: the Tredegar Iron Works site, Gaines’ Mill, Malvern Hill, and the Cold Harbor battlefields.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments