By Peter Suciu

In 1917, after almost three years of hard fighting in World War I, the Romanov dynasty came to an end with the abdication of Czar Nicolas II of Russia. The Bolsheviks made their bid for power and the country was plunged into a full civil war. The glorious decorations and military awards of Russia’s imperial age remained in use among the White armies during the ongoing conflict, but by 1922 most of the fighting was over and the new Soviet Union would introduce its own military orders and awards.

The most common prerevolutionary combat award was the Order of St. George, says noted Soviet collector Dr. Robert Clawson, professor emeritus of European Military Studies at Kent State University. “It was nice for an enlisted man to have one because it exempted him from being beaten by officers. That’s why soldiers wore them on their tunics all the time.” This practice of wearing decorations on combat uniforms, even when in the field, would carry on during the Soviet Union’s titanic struggle against the Nazis.

The Order of St. George was traditionally worn on a ribbon in orange and black, colors that represented fire and death to the Czarist armies. It consisted of three grades and two distinct styles, one for the officer corps and one for enlisted soldiers. Although many White generals considered its use during a time when Russians fought Russians akin to sacrilege, the award continued during the civil war. So did lower grades from the Czarist period such as the St. Vladimir, St. Anne, and St. Stanislas.

For collectors, most of the prerevolutionary and even Russian Civil War-era awards are impossible to find, but reproductions are being made and are sold as such. Clawson also warns that quite a few authentic Czarist crosses and medals can be purchased without their mounting bracket or ribbons, but are often “completed” with reproduction parts.

Beginning of Soviet-Era Awards

Although the White armies continued to wear the decorations of the Czarist era, the Red armies abolished Czarist-era awards and medals along with ranks by the decree of November 10, 1917. The new awards would be made irrespective of rank or social status. The first awards were not medals or decorations at all but gifts, including cigarette cases, watches, and boots. These were given for meritorious service and conduct in the field and for acts of bravery and were generally greatly appreciated owing to their scarcity.

In 1918 the Russian Soviet state introduced the first formal award in the form of the Order of the Revolutionary Red Banner. Other Soviet republics of the future USSR then introduced their own awards. Following the civil war these would be integrated into the Order of the Red Banner for the entire united nation. Until 1926 the award was worn on a red silk rosette, which had traditions dating to the Czarist age. The award held great prestige up until World War II because it was only given to about 20,000 soldiers; until that time, about 15,000 were awarded during the civil war.

The other major award to come out of the civil war was the Honorary Revolutionary Weapon, which was a cavalry saber with a gilded hilt that was presented along with the Order of the Red Banner. For those heroes who had already won this high honor, a special Honorary Firearm was presented—a pistol with the badge of the Red Banner affixed to the grip.

In the post-civil war period a number of awards were issued to soldiers during various uprisings in the new Soviet Republics. Some of these Republics—including Azberbaijan and Armenia—continued to issue their own distinct versions of the Order of the Red Banner. Each of these retained the basic red star with the hammer and sickle but often with the particular region’s own characteristics.

The Order of the Red Banner of Labor was the second national award established by the Soviet Union. It was first issued in 1928 for outstanding service in labor to the Soviet state and society. In the interwar years a number of other awards and decorations would be introduced, including the first Soviet badges. These would include the “To Honest Soldier of the Karlian Front” badge for participation in the 1921-1922 routing of White Finns, and, beginning in 1935, the Order of the Badge of Honor for individual or collective contributions in all spheres of life. This would remain in service until 1988 when it was replaced by the Order of Honor award.

The badges were worn on dress as well as field tunics along with a new style of medals that was first established by decree in 1938. They included the commonly awarded Medal of Valor, for courage and valor in defense of the homeland, as well as the Medal for Military Merit and the Medal for Combat Service.

This period also saw the introduction of the Order of the Red Star, which was presented to ground forces and naval personnel of all ranks for outstanding service in the defense of the Soviet Union. The award, in the shape of large red star with the silhouette of a soldier in the center, was worn on the tunic. It would be awarded almost three million times during World War II.

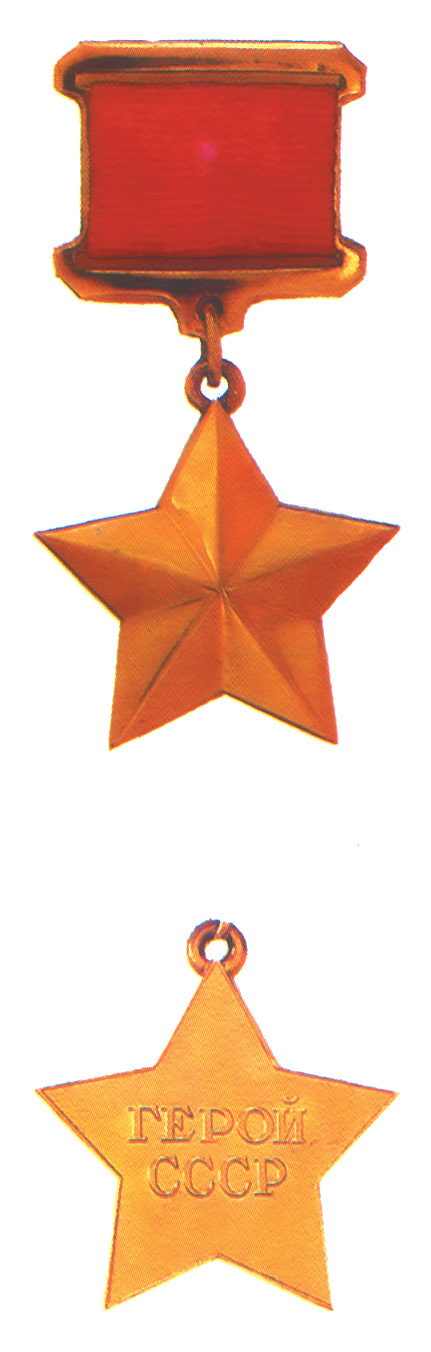

The highest awards were established in the prewar years. The Order of Lenin, established in 1930, was and remained the highest award one could receive. But the highest distinction was the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, introduced in 1934. Both the Order of Lenin and Gold Star have been heavily reproduced and collectors should be wary of most of those that come on the open market.

The Great Patriotic War

The German invasion of the Soviet Union that began in June 1941 caught the Red Army off guard. “Stalin soon figured out that the Soviet population was not going to defend his version of communism so eagerly,” says Clawson. To the Russians, World War II suddenly became the Great Patriotic War for the Motherland and as a result much of the old imperialistic nationalism was revised. It was, after all, the great Russian Prince Alexander Nevsky who had defeated the Teutonic invaders in the 13th century and, nodding to that triumph, one of the first pre-revolutionary awards was resurrected in a new form in World War II.

The Order of Alexander Nevsky was different from the Czarist version and actually featured the profile of the prince over a red star with the infamous hammer and sickle below him. It is worth noting that because no images of the prince were known, the Soviets used the image of the actor who played Nevsky in the 1938 Sergei Eisenstein movie, Alexander Nevsky.

Throughout the war, dozens of various medals, awards, and other decorations would be established. This was especially true as fortunes began to change for the Red Army. “Oddly enough, it seems as if Stalingrad was the psychological turning point for awards,” says Rick Lundström, a collector of Soviet uniforms and decorations for more than 15 years. “Once it was apparent that the Soviet Union would not lose the war, decorations were issued in greater and greater numbers.”

The custom of wearing medals on tunics was once again introduced after being discouraged during the 1930s. The war years saw the establishment of dozens of decorations and today a cottage industry has sprung up offering the awards for sale. There are far too many individual awards to discuss them all, but it is important to note that many continued to be issued well after the end of the war. WWII-era items fetch a higher price, but many postwar items are sold as their wartime counterparts—buyer beware.

For novice collectors there are still plenty of bargains to be had with the numerous “capture” and “liberation” medals that were instituted. These are commonplace today and reasonably priced—but once again there are wartime as well as postwar versions, which were awarded to veterans for years following the war. The actual award consists of a round medal, loop, and ribbon. These were worn on the left breast of both a dress uniform and combat tunic.

The other relatively common decoration that has attracted collectors is the otlichnik or “outstanding” badges. Dealers sometimes call these “excellence awards” and they were devised to indicate that a trainee had reached a minimum level of proficiency in his military occupational specialty. According to Clawson, every branch of service had a series of these awards, which were developed before the war and used for some years after, finally being discontinued in the 1960s. Their purpose seems to have been to imitate the German combat badges and to boost morale in the very dark days. “The Soviets were rather stingy with their combat medals,” says Clawson, “so the other badges were designed to buck up the troops without diluting the real medals.”

Unlike the basic WWII German badges or nondescript American decorations, the Soviet outstanding service awards are actually colorful and highly detailed, complete with the usual red star and accompanying patriotic imagery. They often showed an icon related to the field of proficiency—so an “Outstanding Machine Gunner” award featured a Soviet Maxim machine gun, while an “Outstanding Tanker” showed a Soviet tank.

Today these outstanding awards are reasonably common and affordable, but collectors should tread carefully because there are generally three types on the marketplace today. Those issued before and during the Great Patriotic War are generally easy enough to distinguish from the postwar variations, but the third type are essentially fakes meant to deceive. Detecting substitutes is actually also fairly easy provided you have a reference to compare against. A lack of patina on the metal and smaller diameter posts on the screwback are clear indicators of reproduction. Clawson warns that most of those offered for sale on auction sites are reproductions.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments