By Richard A. Beranty

The attempted crossing of the Rapido River in Italy by two infantry regiments of the U.S. 36th Division in January 1944 was one of the costliest failed attacks made by American forces during World War II.

Nearly 1,700 men were killed, wounded, or captured in this frontal assault aimed at breaking through the Gustav Line near Cassino in the Liri Valley. Originally conceived as a diversionary tactic to occupy German forces during the Allied landings at Anzio, the attempted Rapido crossing ended as an unforgettable two-day bloodbath that achieved nothing for the Allies in strategic gains.

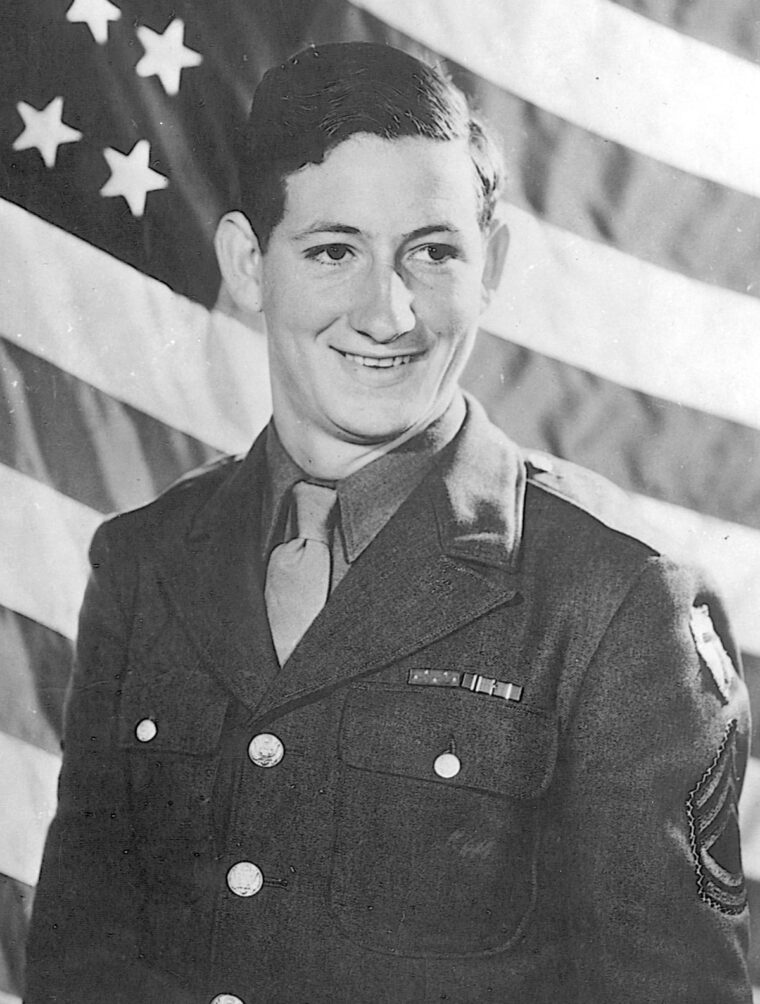

“Everyone was very, very leery about the attack because we all felt sure it was going to be difficult,” says James D. White of Kittanning, Penn., a 19-year-old infantry replacement with the 36th “Texas” Division when the order came to cross the icy-cold and rain-swollen Rapido. “But you do what you’re told.”

The widespread pessimism that pervaded division ranks had more to do with where the attack was ordered than it did with the prospect of facing additional combat. Since spearheading the landings on the Italian mainland at Salerno four months earlier, these once-inexperienced National Guardsmen had been quickly transformed into competent combat veterans. Their fears of doom hinged instead on the location of the attack, an “S” bend in the river where the Germans had constructed a solid wall of defense.

For those men ordered to make the attack, every foot of ground, it seemed, was manned by enemy forces bent on stopping any foray into the lower Liri Valley and gaining a clear pathway to the Italian capital of Rome. Murderous fire from rockets, artillery, mortars, and machine guns behind miles of barbed wire and thousands of mines thwarted two attempted crossings and mauled the hapless “T-patchers” while they struggled to reach the Rapido, fought to cross it, and tried to establish a bridgehead on the other side.

An Indiscriminate Slaughter

“I went across on a little narrow footbridge, about two feet wide, which engineers had anchored to the other side,” White explains. “We didn’t have that far to go, so our whole battalion made it. We no more had gotten across when the Germans opened up on us. The terrain on that side of the river was flat so we started digging in right away. All morning and all day long the Germans poured artillery fire on us. They had us trapped in a pocket. We had the river at our backs and nowhere to go. Guys were getting square hit with mortar shells coming right into their foxholes. My first sergeant was hit with machine-gun fire across his legs. Somebody got him dug into a hole where he took a square hit from a mortar. Because we were dug in so close together, the Germans couldn’t miss us. Guys were being killed all around me.”

The indiscriminate slaughter of men continued unabated throughout the day. There was no way for those stranded on the far side of the Rapido to recross the river and reach the safety of U.S. lines. German artillery crews saw to that by destroying their footbridges. Faced with no option but to fight against overwhelming odds, the T-patchers held their ground until ammunition ran out and the relentless enemy fire overpowered them.

When division casualties were assessed after the attack, there was some question as to whether the 36th could even continue as a fighting unit due to the appalling losses. Back home after the war, division veterans, men who had known combat and the lethal consequences that go with it, were still so incensed over what they felt was a needless sacrifice of human life that they kept a promise they had made years before and thousands of miles away. They petitioned Congress to investigate the Rapido crossing fiasco and take the necessary steps to keep General Mark W. Clark, U.S. Fifth Army commander in Italy, from ever commanding troops in the field again. Their efforts failed and Clark was exonerated. A congressional board of inquiry ruled the attack was necessary and Clark a “middleman” who was simply following orders from British General Harold Alexander, Fifteenth Army Group commander.

Jim White escaped death that day because he was one of the approximate 500 36th Division soldiers taken prisoner. He spent the rest of the war in a German POW camp. But his memories of that cold January day, of dying men and the punishing German guns, have haunted him ever since.

“I do feel a little bit guilty about surviving,” he says. “How did I make it back when all those other guys around me didn’t? And I’m sure they had parents at home praying for them, the same as my mother and dad were praying for me. How did guys as close to me as five feet away get hit and I didn’t?”

White’s journey across the Rapido began on May 12, 1943, when he was drafted and sent to the Infantry Replacement Training Center at Ft. McClellan, Ala., for 17 weeks of basic training. He boarded a Liberty ship at Newport News, Va., on November 3 and reached Oran, Algeria, 21 days later.

“From Oran we shipped over to Naples in early December on an LST,” White says. “From there we went into a replenishment depot. We knew we were going to replace somebody in the infantry.”

The need for replacements had been constant for the 36th in the early days of the Italian campaign. Since its September invasion at Salerno, the division had endured hard and continuous fighting on or near the coast, depleting its ranks considerably. Four days alone were needed to clear the Salerno beaches, and fighting in the hills above the Italian seaport grew even more intense.

At Altavilla, Corporal Charles E. “Commando” Kelly of Pittsburgh, America’s first Medal of Honor winner in Europe, held off a German attack alone by throwing mortar shells at the enemy from a second-story balcony. At Monte Rotondo and Monte Lungo, the division was under fire for 24 consecutive days and nights. In battles around San Pietro, the 36th Division suffered 2,400 casualties. This was fighting, however, that many in the division had not anticipated

One day prior to their September 9 landing, news was announced of Italy’s unconditional surrender, and optimism soared among the troops still on ships off the Italian coast. They thought the liberation of Italy would be an easy ride. Their hopes, however, were short-lived. German troops still garrisoned the country and were not about to withdraw. The ensuing campaign would see some of the bitterest fighting in the European Theater against a very stubborn, well-led, and well-equipped enemy. And with so many new faces arriving to fill the empty slots, the T on the shoulder patches of division soldiers now stood for just about anywhere.

“Most of the men were originally from Texas, close to the majority were,” says White. “But with so many casualties they were pretty depleted when we went in. When I joined up with them, the division had recently been pulled off the line. It was on break. As soon as we replacements arrived, the division moved up to the front.”

Frozen Feet and Foxholes

It had been raining when White joined the 36th, first assigned to a rifle company and then later to a 60mm mortar squad in Company K, 3rd Battalion, 141st Regiment. Day after day of cold winter rain left much of the countryside an endless expanse of mud. Foxholes, normally a soldier’s only refuge on the battlefield, were filled with water. Trench foot was common. Life on the line meant continuous movement, poor food, wet clothes, and cold feet.

“You’re in a foxhole for a while, then you move up,” White recalls. “You might spend one or two nights in the same place, then move forward. It was raining all the time, and it was cold. My feet were frozen. Most of the guys had frozen feet. They told us not to take our boots off because you never knew when we might have to get out of somewhere in a hurry. And if we did take our boots off, you might not be able to get them back on because your feet would swell up.”

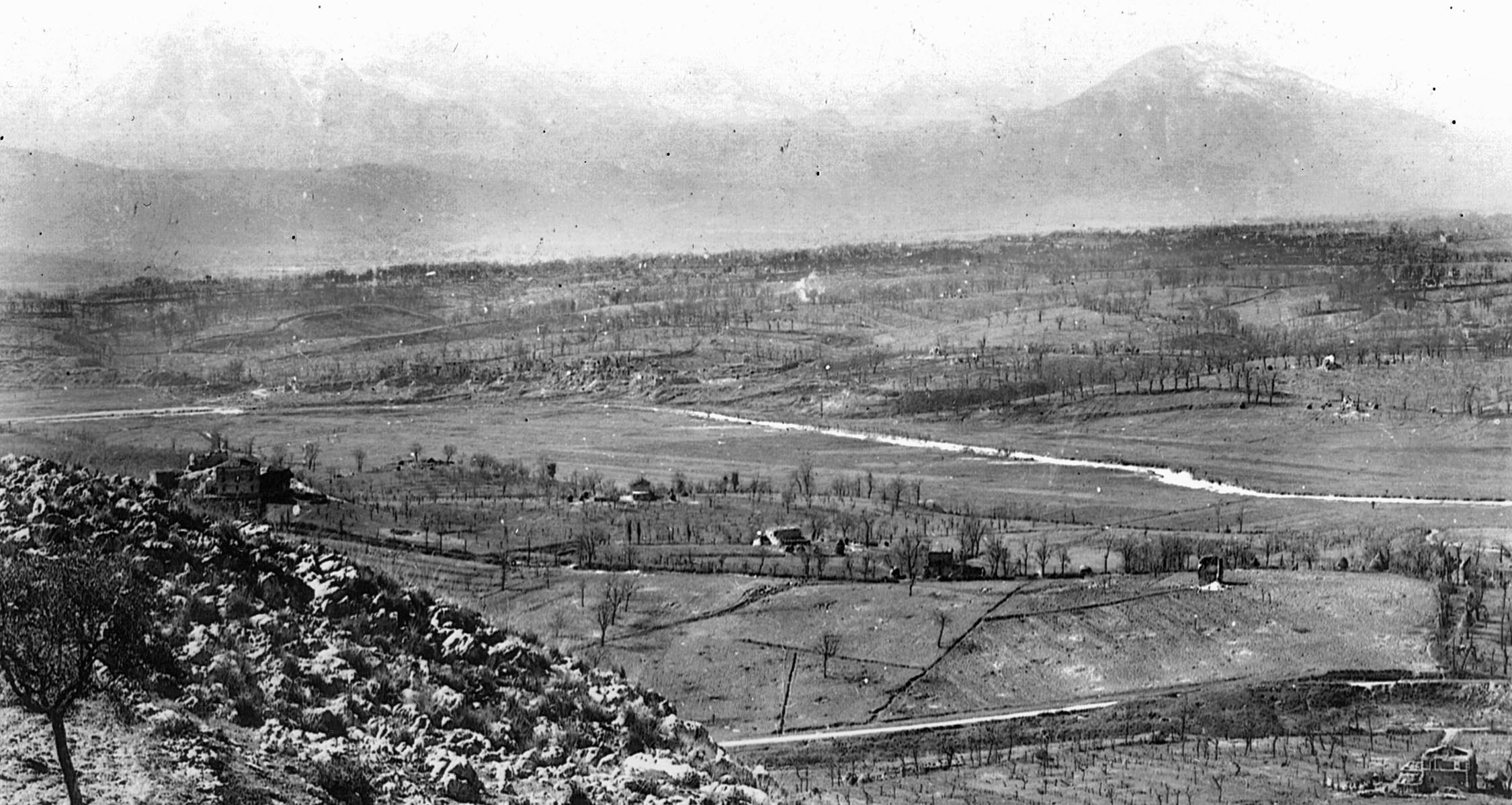

By mid-January, the 36th was positioned on the west side of the Rapido River with the crest of Monte Cassino and its ancient Benedictine abbey looming far in the distance. The gloom the soldiers felt about any upcoming assault was shared by General Fred L. Walker, commander of the 36th, who had pleaded with Clark to reconsider the Rapido attack. Walker, an infantry major in World War I who was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for heroism at the Marne River in France, had been the division’s commanding general since September 1941. He knew the Germans were deployed in strength along the banks of the Rapido, but he had another reason to feel pessimistic about the upcoming attack. The 36th at that time was not a top-notch fighting outfit. It had been battered at Salerno and beyond, and many of its officers were new and not yet acquainted with the men.

“A company commander didn’t last long,” White offers. “General Walker was definitely against the crossing but he was following orders from above.” Since the 36th was deemed the most rested of the available divisions, it was picked for the assault.

On the enemy’s side of the river were troops of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division under the command of General Eberhardt Rodt. It was part of XIV Panzer Corps, headed by a former Rhodes scholar, General Fridolin von Senger, attached to the German Tenth Army under General Heinrich von Vietinghoff. In overall command of German forces in Italy was Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, a defense-minded general who had previously headed Axis forces in Sicily and served as Luftwaffe chief in North Africa. These men knew the Americans were readying an attack as U.S. patrols had crossed the river several days before. The resulting skirmishes alerted them enough to double their efforts to fortify the low terrain by stringing more barbed wire and cutting away trees that hindered fields of fire. Clark ruled out a daylight crossing and ordered a night assault.

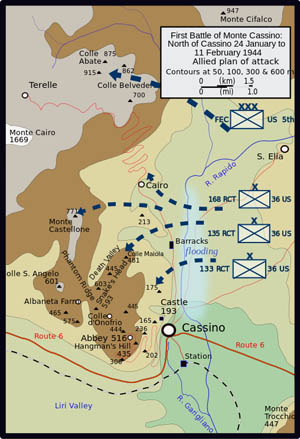

The first part of the Allied plan to break the winter stalemate at Cassino called for French forces to cross the Rapido and take the hills to the north while the British attacked in the south. The 36th was then to deliver the main assault in the center. After the T-patchers established a bridgehead, the U.S. 1st Armored Division would cross the river, go through the 36th, and speed northward up the Liri Valley.

“I don’t see how they could have possibly gotten tanks, let alone bridges, across that river,” White says. “We could look out and see it before we crossed. It’s called a river, but I would call it a stream. Where I crossed it was no more than 15 to 20 feet wide. But it was a real fast moving stream. It was a mountain stream, deep and very swift.”

Part two of the Allied strategy involved the massive buildup just off the western coast of Italy, which was ready to put troops ashore at Anzio and Nettuno beaches to coincide with the 36th attack. These landings were intended to flank the German forces out of their strong positions on the Gustav Line. The latter would be deemed a success if it did nothing more than prevent the Germans from moving against the Anzio beachhead. It would be an even greater success if the two forces could link up and head toward Rome. However, neither outcome materialized because of the lethargic movement of the Allies to break out of the Anzio beachhead and the failure of the Rapido attack. Kesselring, taking full advantage of interior lines, held off his enemy on both fronts by moving troops freely between them.

On January 12, French forces, including Moroccans and Algerians, began the attack on the right. After four days of close fighting, some of it hand-to-hand, the French Expeditionary Corps was halted. Only about four miles had been gained in the effort. On January 17, the British X Corps began its attack on the left across the Garigliano River. Kesselring was fearful that this force would breach his line, so he pulled two divisions away from Rome and the fighting ended in a stalemate.

Without protection on either flank, Clark gave orders for the 36th to attack on the night of January 20 near the village of Sant’ Angelo just south of Cassino. To soften up German defenses, 16 battalions of Allied artillery bombarded enemy positions, but it was not enough to give American troops a real chance at success. The division’s 141st and 143rd Regiments began the crossing with the 142nd held in reserve. Troops were to cross over in wooden boats and rubber rafts or on footbridges erected by the division engineers.

“We tried crossing at about 2 in the morning,” White says. “The first night we tried, we didn’t make it. We got pushed back. The engineers were to have cleared the minefield going down to the river. We were to follow strips of tape, white reflective tape that we could see at night. My squad leader was up ahead of us, and I don’t know whether he stepped over the tape or the engineers missed a mine. I don’t know what it was. But anyhow he tramped on a mine, and it blew his leg off just below the knee. He was conscious though, and a couple of guys put a tourniquet on it.”

Getting to their crossing sites was further hampered by heavy winter rain that had fallen for days along with melting mountain snow. These combined to flood lowlands, leaving a quagmire of marshes. Despite the efforts of engineers to remedy the situation by spreading gravel over the sodden soil, the ever-present mud prevented trucks from supporting the attack, so troops had to carry assault boats and cables to the river. For about two miles, soldiers lugged these bulky 24-man rubber rafts and ponderous 12-man wooden assault boats to their crossing sites, the latter measuring 13 feet long and weighing more than 400 pounds.

30 Men Lost in a Single Volley

German shelling was encountered about a mile from the Rapido, and chaos reigned in the winter darkness. One company had its commander killed, its second-in-command wounded, and 30 enlisted men lost in a single volley. Explosions punctured the rubber boats and splintered the wooden ones. Tape indicating the way was torn up and buried in the mud. When the 141st finally made it to the river, about one-third of the boats could not be used. Troops laden down with weapons and ammunition tried to board the undamaged boats swinging crazily in the current.

While some craft got across, some were hit by artillery fire, some capsized, and some were swept downstream. Four footbridges were to have been erected, but the engineers had managed only one. Two companies used it until it was destroyed. By 10 am, the initial attack was called off, and the gunfire of those 36th Division soldiers who had crossed grew more and more quiet. White says he carried a mortar slung over his right shoulder during this first assault and a 30-caliber M-1 carbine positioned horizontally across his shoulders.

“We were getting shelled, so of course I hit the dirt two or three times,” he says. “Every time I did I always reached back to make sure my gun was still there. One time I reached back and my gun was gone. I didn’t know where it was. I thought, ‘Oh, man! What am I going to do now?’ So we got back to our positions and I told my squad leader, ‘I lost my carbine.’ One of the guys in my squad was carrying a .45, and he had to go back to the medics. He was sick. So he said, ‘I’ll leave you my .45.’ Well, I had never fired a .45 before. I didn’t know much about a .45, but I thought it was better than nothing. So I took it.”

White also lost his glasses during the shelling. “I’ve always worn glasses,” he continues. “When we were getting shelled, I hit the dirt, and the concussion knocked my helmet off and pulled my glasses off at the same time. It was dark, and I was feeling around, trying to find them, and the company was moving on. So I picked up my helmet and kept on going. I didn’t have glasses until I returned to the States.”

Ordered back to their previous positions following the failed crossing, morale among the T-patchers was even lower than it had been before. Men cursed and prayed that the assault would be canceled. “Boy, we were hoping that they would change the plan,” White says. “We thought surely they wouldn’t try it again.”

But they did. On the following night, January 21, the same two regiments were again ordered to cross the river.

“On the second try we more or less came down the same path,” he says. “But there was no enemy fire. Everything was quiet. The Germans just let us come down.”

White says the German strategy of allowing the early units to cross the river unmolested and then letting loose with everything they had worked to perfection. First the boats were targeted; then the newly erected footbridges were destroyed. That accomplished, German gunners went to work on the stranded GIs. By that time dawn had started to break, and White was one of those facing methodical destruction. It included the use of the six-barreled Nebelwerfer rockets dubbed “screaming meemies” because of their distinctive and terrifying sound.

“You could hear them coming. They go ‘whrill, whrill, whrill.’ The sound alone scares you as much as anything,” White remembers.

As the day wore on, no support arrived for the stranded T-patchers. A third attack, which would include the 142nd Regiment, was considered by General Geoffrey Keyes, II Corps commander, and canceled only after Walker lobbied heavily against it. Still, the men on the far side of the river held out. By afternoon the Germans launched a series of counterattacks that were beaten back by the hard-pressed Americans. The enemy’s withdrawal was followed by German artillery fire that zeroed in on the areas marked by their previous attacks. Those T-patchers still alive were dug in and hunkered down, trying to offer as much resistance as they could while facing withering fire from the Germans.

“We held out that first day,” White says. “We got some Germans. They didn’t get us that first day. So the next morning several of us, the ones who were able, got back down to the bridge where we had crossed. Here, the Germans hit the bridge, a square hit, and it was knocked out. We were trying to figure out how to get back across the river, and this one fellow with us said, ‘I’ll try to swim it. If I get a rope across maybe we can get back.’ So we put a rope around him and he tried to swim. But he couldn’t. The current carried him downstream. We pulled him back in and it was just breaking daylight. This would have been the 23rd of January, and the Germans saw us. I think they thought everybody had been wiped out the previous day, and as soon as they saw us they opened up again.”

143 Killed, 663 Wounded, and 875 Missing

With the 36th now just a shell of its former fighting self, the attack was stopped 48 hours after it started. Without making a dent in the German line, the division had suffered 1,681 casualties, including 143 killed, 663 wounded, and 875 missing. Remarked one company commander, “I had 184 men … 48 hours later I had 17.” White was taken prisoner about 100 yards from the river with as many as 50 others, including his company commander and platoon leader. He was searched, allowed to keep his dog tags and Bible, but did have his field jacket taken from him. “The Germans wanted that for themselves to keep warm,” he says.

The captured T-patchers then feared the worst. “We didn’t know what was going to happen,” says White. “We thought they might shoot us because they took us down over a hill, and I thought, ‘My God, this is it!’ But all they wanted us to do was gather some dead German soldiers and bring their bodies back. So we did that. Then they started moving us behind the lines until we got back to another area, like a small prison camp. We were there for a couple of days and lived in tents. It was cold.”

Their days as frontline soldiers now over, the prisoners were crowded into boxcars in a train bound for Germany and 14 months of imprisonment. White says he is not sure how long the train ride lasted.

“You lose track of time,” he says. “You’re in there, locked in and shut in. We couldn’t see out, and we didn’t get fed, so I lost track of time. I would guess two or three days, but I couldn’t say for sure. Inside the boxcar we were right up against each other, standing up the whole time. There was no room to hardly even move. And my feet were frozen so badly I couldn’t stand anybody touching them. To relieve ourselves, there was a little keg in the middle of the car with only enough room for one person. Once somebody got on there, we had to wait.”

The train’s first stop was Stalag 4 B at Muhlberg along the Elbe River, a British POW camp where White was registered and given his identification tag. “The British tried to help us as much as they could,” he says. “I do remember that they had a big tub of soup waiting for us and they did give me a British Army jacket to replace the one taken from me. It was one of those short coats, sort of like an Eisenhower jacket. They also taught me the first German words I learned: ‘Dahl mager.’ They said if you get into any trouble with the guards and they try to hassle you, say ‘Dahl mager.’ Apparently it meant that you didn’t understand them and you needed an interpreter.”

After a few days at Stalag 4 B, White was moved to permanent quarters, Stalag 2 B at Hammerstein in northeastern Germany near the present-day Polish city of Szczecinek. Enlisted men and NCOs were housed in long barracks ringed by fences, barbed wire, gun towers, and guards. White estimates there were about 2,000 prisoners in the main camp, some of whom were also from the 36th. “There were guys from the division, but none from my company. Not too many of them were left.”

The Germans in charge of the camp did not feel compelled to supply the prisoners with a decent meal. They were fed once a day in the evening. “For food they gave us some kind of weak soup and a loaf of bread. That had to be divided between seven guys,” White remembers. “We would measure it up exactly because it meant so much. I know the bread was made of sawdust because you could see the sawdust in it. You could tell it was sawdust.”

It was during his stay in the main camp when White witnessed an event that, to this day, hurts him to remember. “I hate to talk about it because I’m so ashamed of it,” he says. “When you were a prisoner, one thing you didn’t do was steal from another prisoner. Anyway, there was one fellow who was accused of stealing something from another. They had some kind of kangaroo court over it all and they found him guilty. They took him outside to the latrine and put him in head first. I can’t imagine anyone doing something like that to another, especially a fellow POW. It was awful. Then they put a sign on him, ‘I am a thief’ and paraded him around. I felt so sorry about what happened to that guy. I didn’t take part in it at all, but I still feel ashamed about it.”

Not long after his arrival at Stalag 2 B, White was sent on a work party. He lived away from the main camp for the remainder of his imprisonment in a smaller, barbed-wire enclosed compound, housed in a building with bars on the windows. While some prisoners worked on nearby potato farms, White cut timber in a forest with 19 other men. To supplement their meager rations, Red Cross parcels arrived, containing one can of Spam, one can of corned beef, liver spread, a package of cheese, dried milk, instant coffee, a package of prunes or raisins, powdered orange drink, sugar cubes, crackers, two chocolate bars, two bars of soap, margarine, five books of matches, and four packs of cigarettes.

“Getting Red Cross parcels was the only thing that kept us going,” White admits. “We were supposed to get one a week, but we didn’t always get them once a week.” Baths were just as uncommon an occurrence. “When I was first captured, I went several weeks without a shave or a shower. The first time in the main POW camp we were given a cold shower. In the work camp we eventually were given a tub and we heated water and bathed once a week.”

Back home in western Pennsylvania, White’s parents received what every parent with sons in the service dreaded at the time—a Western Union telegram. It is dated March 13, 1944, and remains in a scrapbook White’s mother put together. It reads as follows:

“The Secretary of War desires me to express his deepest regret that your son Private James D. White has been reported missing in action since 23 Jan in Italy period If further details or other information are received you will be properly notified.”

“I guess it was pretty hard on my mom,” White says. “Her health wasn’t too good to begin with and I was an only child.”

A second telegram, dated April 14, 1944, arrived at his parents’ home with somewhat better news.

“Based on the information received through the provost marshall General records of the war department have been amended to show your son Private James D. White is now a prisoner of war of the German government.”

“That telegram relieved my mom considerably,” he says. “At least she knew that I was alive.”

With his POW address in their possession, White’s parents began sending letters, food packages, and cigarettes to their son. Several order receipts for Camels, mailed to servicemen at the time by the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, are contained in White’s scrapbook. One is dated August 14, 1944. The cost of the order was $1.41.

“My parents knew I didn’t smoke, but they thought I could use them to barter,” he says. “Once in a while you might find a German guard who was willing to trade. We always said to them: ‘Havensee brot for kaufen?’ That meant, ‘Do you have any bread for trading?’ Most of them smoked and some of them were willing to trade.” Health care for the prisoners, at least that provided by the Germans, was non-existent. “There was an American doctor with us who had been taken prisoner and was sort of looking after the POWs.”

Dreams of Escape

White says one visitor to his work camp surprised and amused him. He was a German Luftwaffe pilot, apparently from New York City, who spoke impeccable English. “He heard that there were American POWs near where he was stationed, and he came up to our work camp, stood outside the fence, and talked to us for about half an hour one day,” White relates. “He told us how his family came to the U.S. I’m not sure if he was born here or not, but he spoke perfect English and talked to one of our guys about places around New York. He said in 1939 his family sent him back to Germany to visit his grandparents. By then Hitler would not let anyone return, and he was inducted into the Luftwaffe. I remember him saying how he knew they would never send him to the American front because he would take the plane to the American lines and land it. He was certain that he would be going to the Russian front.”

With dreams of escape on the minds of many American prisoners, White says he never seriously considered it. “I could see where you had chances to escape,” he says, “but where are you going to go? There’s no place to go. You don’t have any outside contacts and you don’t know the language.

“But we did have two guys who made up their minds that they wanted out,” White continues. “You get to a point like that—frustrated. They said they were going to try to escape. So we watched the guards. They took roll call twice a day; once in the morning and again in the evening. They would come in through this big door, through a barbed-wire enclosure, which had a lock on it, and on Saturday nights they got into a bad habit of coming in through that big door and not locking it behind them.

“So we saved these guys as much food as we could. One night, as soon as the guards came through this big door, it was dark in that area, these two guys went past them and got behind the door.

When the guards went past, the two went out through the door, underneath the barbed wire and got going. When the guards came in for their count, we moved around a lot so they didn’t really get a good count. Then they left. The next morning, I remember it was a Sunday, they started counting us. We were trying to move around to keep them from getting the right count again, but then all of a sudden they realized that two men were missing. Then they ran around pulling on the window bars and looking for tunnels. Their superiors weren’t happy with them at all for letting those two get away.”

Local civilians, after a day or two, saw the escapees in a field and reported them to the Germans. “They did bring them back, but took them away and I never saw them again after that. I don’t know what happened to them,” White says.

As Germany’s lines in the east collapsed before the onslaught of the Soviet Red Army, White’s days as a POW were numbered. “We knew the Russians were coming,” he says. “We would get bits and pieces of news. They weren’t that close that we could hear them, but they were in eastern Prussia and coming our way. So the Germans started to round us up and move us west. Every day, we were on the move, about as far as you could walk in a day’s time, for two or three months. We ate whatever we could find along the way, such as potatoes. At night they would find a farm and pull us into a barn to sleep.”

About 300 prisoners were in the group headed westward, and they walked nearly 600 miles before being liberated by an American armored column near Frankfurt on April 13, 1945, the happiest Friday the 13th in White’s life.

“We heard firing and saw fighter planes overhead, so we knew Americans weren’t too far away. These fellows in jeeps and armored cars came up and found us. The German guards turned their weapons over to us. There was one guard who had a dog, and it was mean. He’d sic that dog on the prisoners. A lot of the guys were determined to do something to this dog. But before they had a chance to do anything to it, the guard shot the dog himself.”

The former prisoners were told by the Americans to stay where they were until other U.S. units arrived. “We were in a little hamlet with about half a dozen houses. The Americans didn’t have any rations to give us, so we found some chickens and cooked up a big meal that night. Then we moved into these civilian houses and stayed there for a couple of days,” remembers White.

Inside one of them, the former prisoner located a pencil and paper and wrote a letter to his parents. It survives, on very thin onion-skin paper.

Sunday Morning

8:30 am

April 15, 1945

Dear Mom & Dad,

I guess this is the happiest letter I have ever written. Friday, April 13, at 3:00 pm, we were recaptured by our own boys. I really felt like crying when I saw our own tanks coming down the road toward us. Many of the boys did for that matter and the fellows that recaptured us were just as happy as we were. The rest of my life I know that Friday the 13th will be my lucky day. We are patiently awaiting our return to good old America, a heaven on earth, your lesson, after spending 15 months in this damn Germany.

I guess you have been worrying about me for the last two months. Well the complete story will have to wait until I get home but here is a brief summary: If you didn’t know, we were imprisoned near the Polish border about 90 miles from Danzig. The Russians made a big offensive and the Germans moved us about 900 kilometers by foot to western Germany where we were so lucky to be recaptured by our boys. We walked for eight weeks. But every step was worth it just to see good old American doughboys again. Well I’ve seen most of Germany and I don’t believe this war can go on much longer. These “Dutchmen” have practically nothing left. The GI’s are on the move now and really traveling.

I don’t know how long it will be before we are sent back to the states but two Generals told us yesterday it would be as soon as possible. So maybe I’ll see you before long.

We’ve had some pretty tough times in our imprisonment in Germany but they are all over now. I have so much to tell you but it will have to wait. Tell everyone I said “hello” and I wish I could write to all. This letter is being written on captured German stationery. I doubt if the censors can read this letter. I’m so excited I’m just scribbling it out. Give my love to all. I must say so long now.

Your loving son,

Jimmy

Soon after White wrote the letter, the men were moved by trucks to an airfield from where they were flown to France, staying there a few more days before being sent home from Camp Lucky Strike in Le Havre, one of the major embarkation points for returning GIs.

“The Heroes Were the Ones Who Didn’t Make it Back”

White boarded a hospital ship on April 27, which first made port in Southampton, England, to pick up wounded soldiers, and arrived at Staten Island in New York harbor on May 13. From there, he was sent to Ft. Dix, NJ, given a 60-day furlough to visit family and friends at home, and ordered to Atlantic City for seven days of testing. “We stayed at one of those big hotels on the boardwalk,” he says. “I had my teeth fixed and my eyes tested. That’s when I finally got glasses again.”

The hotel that White stayed in was one of the most impressive in Atlantic City at the time, the Hotel Dennis. It housed the Army Ground Forces Redistribution Station where men were examined to determine their fitness for future assignments. Following these tests, White was assigned to Camp Livingston, La., to help train recruits in a rifle company. “While I was at Camp Livingston, the war with Japan ended and they started closing down these camps because they weren’t needed,” he says. “I still didn’t have enough points to get out of the Army, so I was shipped to Camp Roberts, California, to train those headed over to occupy Japan.”

White was discharged in December 1945. Looking back on his war service, he is amazed that he returned home while so many others didn’t. “I don’t consider myself a hero,” he says. “The heroes were the ones who didn’t make it back. Pauline [his wife] always said that God had a purpose, that I was meant to look after my mom and dad, and then to look after my mother after my dad died. I don’t know what it was. But I do feel a little bit guilty. Maybe I should have died there, too, along the Rapido. But that’s fate. You don’t know what’s going to happen in life.”

HELLO, DOES VETERAN WHITE STILL SURVIVE?