By Bruce Graham

It was the worst of times for the Allies. It was the time of opportunity for senior U.S. military officers. It led to frustration for two apparent shoo-ins for important commands and signaled a meteoric rise for a hitherto obscure officer.

The time was the first few weeks after Pearl Harbor, when the eyes of Allied leaders were focused on Malaya, Thailand, and Burma and the impact of the Japanese advance on China’s survival as a fighting ally. The American public was fascinated with the rumors of Japanese attacks

on the West Coast and the trauma in the Philippines.

The American leaders were not anxious over the safety of California, but they also knew what they dared not admit to the public: The fate of the Philippines was already sealed, and that the foci of the conflict were shifting rapidly, at the initiative of the enemy, in ways that imperiled the continuation of China among the combatants.

The two high-ranking Army officers involved were Generals Hugh A. Drum (1879-1951) and Joseph W. Stilwell (1883-1946).

Drum’s Rise to Commander of the First Army

Each of these officers had distinguished careers. Drum, had served as General John J. Pershing’s chief of staff in France in 1917-1918. He had been involved in the chaos surrounding the Allied entry into Sedan, an unfortunate episode that seemed to have no adverse impact on his or his superior’s subsequent careers. He advanced in rank through the postwar emasculation of the Army and rose to command the First Army in New York.

Drum, one of few active officers with experience as a general in World War I, was the senior officer of the Army. He had been passed over three times for appointment as chief of staff. Drum believed, based on a 1939 conversation with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, that he would be given command of an American force in Europe should another conflict there involve the United States. Yet, when the new Army chief of staff was appointed during the summer of 1939, the position went to a man to whom Drum and 33 other generals were senior: George C. Marshall.

Stilwell’s Background

Stilwell had risen from first lieutenant in 1916 to temporary colonel in 1919, then reverted to captain during the postwar demobilization. He served extensively in the Far East and was twice military attache in China, most recently from 1935 to 1939. However, on the eve of war in Europe, he was only a colonel. He had attended and then instructed at the Fort Benning Infantry School. He was highly regarded by the new chief of staff as an officer of talent, vigor, and initiative, the sort of man that should advance in the hierarchy.

Mobilization raised Stilwell to brigadier general in August 1939, and to major general in September 1940. He invested initiative, dedication, and a commitment to excellence in every assignment and displayed a willingness to share the hardships of his subordinates. These were qualities allowed him to achieve a good measure of success early on, until he was sent to Southeast Asia.

Stilwell, however, was often of a sour disposition, which had earned him a nickname that he did not resent: “Vinegar Joe.” He possessed an abrasive, severely judgmental and even paranoid temperament. It was perhaps his frustration in so many plans in Southeast Asia, despite his wholehearted dedication to the tasks, that contributed to Stilwell’s bitterness, anger, and eventual eclipse.

Allies Try to Put Off Dealing with Southeast Asia

During those early post-Pearl Harbor days, the Allied military situation in China and Southeast Asia was in disarray. The Japanese were advancing toward the British fortress of Singapore with a speed that disrupted plans for resistance. They were established in Thailand and seemed to be preparing to advance into Burma. Japanese objectives were to use Burma as the southwestern anchor of their expanding empire and to sever the final remaining pipeline for Allied supplies into China, the Burma Road.

The Allies, of course, did not know the enemy’s intent, but were certain that the future of the Burma Road was at issue. In any event, the Japanese offensive did not stop until it reached the eastern frontier of India and shut down the Burma Road. The arrival of the monsoon season and the Japanese decision not to persist on the offensive ended the push westward. The Imperial Army was not prepared to attack India, having learned some bitter lessons during five long years of war against China. Apparently, the Japanese acknowledged that subduing the vast Chinese territory was a daunting task. They were, therefore, content to close the ring on the Nationalist/Koumintang government.

Dealing with the immediate Japanese offensive was only part of the equation in Asia for the United States. The nation’s highest leadership was also faced with varied diplomatic military problems which impacted each other usually in negative ways. In the classic phrase, dealing with the Southeast Asia problem was like playing pool on a cloth untrue with a twisted cue and elliptical billiard balls.

The Southeast Asia crisis was of immediate concern to the United States, China, and Britain, yet the United States and Britain were agreed that, beyond the shortterm, the European Theater must take priority before the Allies could take the offensive against Japan. The United States and Britain, therefore, were coldly determined to limit their long-range commitments to Southeast Asia to only what was necessary to permit China to continue fighting the Japanese.

The Confusing Situation in China

The Chinese military was a confused melange of Nationalist/Koumintang elements whose history went back less than 20 years. Remnants of warlord forces in some localities still were more powerful than the central government and the tightly disciplined Communists. The Communists had actually served as the spear point of Soviet expansionism in the Far East, occasionally fighting the Japanese.

The Nationalist government was demanding a huge volume of arms, ammunition, and other supplies. Their stated requirements were simply beyond the capacity of the Allied supply system. Washington was intent upon at least appearing to comply with their requests.

Meanwhile, the Chinese Army was hobbled with poor generalship at the field level. At the end of 1941, Washington and the Nationalist/Koumintang leaders tentatively agreed that an experienced, high-ranking American officer in China and Southeast Asia would provide skilled command assistance. This officer would closely and congenially associate with the highest level of the Nationalist/Koumintang government.

Additionally, at that time, the non-Chinese battle areas were defended by Chinese and British Empire and Commonwealth units, with no U.S. ground forces engaged. Further, there was no prospect for direct ground involvement by U.S. troops in the near future. Thus a U.S. officer would be in comman d of a variety of military units, each with it’s own command structure when there was no American military investment in the field or governance of the areas affected by the outcome.

The American officer selected would be expected to possess diplomatic skills sufficient to keep the various balls in the air without grating on any of the participants or undermining the American effort. Compounding the problem was the contemporaneous involvement of the U.S. political and civilian leadership in the person of Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and the military arm, represented by the chief of staff, in the appointment of the officer and follow up supervision.

Finally, there were the conflicting demands of the European, Asian and Pacific Theaters, the first two further affected by the often varying desires and plans of Soviet Russia, which was legitimately viewed with suspicion by other Allied governments. It was into this stew of many different ingredients and seasonings that generals Drum and Stilwell were drawn.

The nominal head of the Chinese government, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, asked for the appointment of an American officer of high rank to serve in a nebulously defined capacity. He asked for an officer without previous experience in China who would be loyal to the Nationalist/Koumintang government only and not influenced by government and military methods prior to the establishment of Nationalist/Koumintang hegemony. Washington’s first choice was Drum, who was without experience in China.

Stilwell was tentatively slated to lead an early Allied operation in North Africa. This operation was tentatively high on the agenda for 1942 and was being intensely studied by British and American planners. When asked for a recommendation for appointment to Southeast Asia, Stilwell recommended Drum as a leader who would “insist on his dignity.” Stilwell felt that his own experience in China as a “small fry colonel,” who the Chinese had seen “on foot in the mud, consorting with coolies, riding soldier trains” left him without “face.”

It is unclear whether Stilwell made the recommendation based on his desire to fortify his position as the proposed leader of the North African effort by getting Drum out of the way, because he wanted to avoid the Southeast Asia assignment, or out of simple honesty.

Drum Disappointed at Being Offered Southeast Asia

Drum was summoned to Washington early in January 1942. He arrived with an entourage, anticipating that his high position in the Army hierarchy was about to land him the revived post of his mentor, General Pershing, as commander of the American, if not Allied, forces in the European Theater. He met with General Marshall and the secretary of war and was taken aback when he learned of his proposed appointment to Southeast Asia. They, due to their different perspectives, presented Drum with seemingly inconsistent outlines of the purposes of his assignment.

Crestfallen, the general stalled for several days. It may be surmised that by avoiding the Eastern assignment he hoped to increase, or at least not hurt, his chances of the European command. He might have preferred to pass on the Southeast Asia post, which had much greater potential for defeat before ultimate victory. Perhaps the position even lacked the possibility of ultimate victory. It could be that Drum was genuinely confused by the conflicting military and diplomatic situations. Or it might be that he was simply deflated and preferred to exercise “one-upmanship” before accepting.

In any event, Washington concluded that Drum was balky and uncooperative. He was left alone and thereafter was out of the picture, both in the Far East and in the European Theater. Perhaps this was what General Marshall intended. Marshall was determined to bring new officers to the war effort, and this may have been a subtle way to shunt Drum aside in favor of more agreeable people.

Attention Turns to Stilwell

At the same time, the North African project was, for the moment, dropped from consideration. Instead, a study was made of a cross-Channel landing in France, slated for 1942 or 1943, which was intended to relieve the pressure on Russia.

With the North African plan shelved, the secretary of war told Stilwell that his destiny appeared to be in China. When he was called on to fill the Southeast Asia position, Stilwell’s response was, “I’ll go where I’m sent.” Again, it is an open question as to whether he was genuinely self-sacrificing or resigned to the fact that if he declined he would receive no other appointment of consequence. He may have believed that if he accepted the job he would still be considered for a more illustrious command, or perhaps he felt that he would genuinely be able to change Allied fortunes, at least in the short term in what was viewed as a critical theater.

So, Stilwell went to Southeast Asia and his rendezvous with heroism, frustration, disappointment, hard work, and, ultimately, removal under the stigma of having failed, leaving the job undone.

The Path Upward Opens for Eisenhower

When Drum was conferring in Washington, one of the officers with whom he met had, to the delight of his superiors, served in a number of subordinate positions–including former Army chief of staff General Douglas MacArthur–this was Dwight D. Eisenhower, a recent recipient of a first star, who was serving in the War Plans Division. Eisenhower’s record of steady determination and endurance during difficult projects in the pre-World War I and interwar military had marked him for high assignment.

It appears, even at this early date, that Eisenhower was on a “short list” for rapid advancement to high command, largely on the basis of his self-effacement, humble background, widely regarded thoroughness, skill in staff work, and patient finesse in dealing with officers whose exalted ranks often were accompanied by large egos. During World War II he was able to handle several U.S. and Allied personalities occupying high posts with strong determination to have things their way. To the extent that Washington sought this type of character as an important element in achieving victory in Europe, the judgment was correct.

Drum’s rejection for high appointment could be traced to his pride of place. This pride would have caused difficulties in either Europe or Southeast Asia, where there was no room for a commander who would exercise exclusive authority and command and expect to receive strict obedience from subordinates and backing—whether grudging or enthusiastic—from superiors, as with MacArthur in the Pacific. A capacity for patient endurance and diplomatic skill was paramount in both theaters. So, the decision to bypass Drum was justified by the requirements of military and diplomatic grand strategy.

Stilwell’s Quandry: Trying to Serve Two Masters

It is interesting to consider Stilwell’s position vis-a-vis the other players in Southeast Asia in the spring of 1942. He labored under British Prime Minister Winston Churchill through subordinate theater commanders. He was also subordinate to the Chinese generalissimo, chief of staff of the Chinese Army, in toto, and the U.S. president and chief of staff.

Seldom in the history of warfare has there been a better or more bitter example of the Biblical maxim, “No man can serve two masters.” Inherent in this confused mixture of responsibilities were multiple conflicts in loyalty, obedience, and objective. These conflicts took their toll on Stilwell, who was both the cause and the victim of myriad problems.

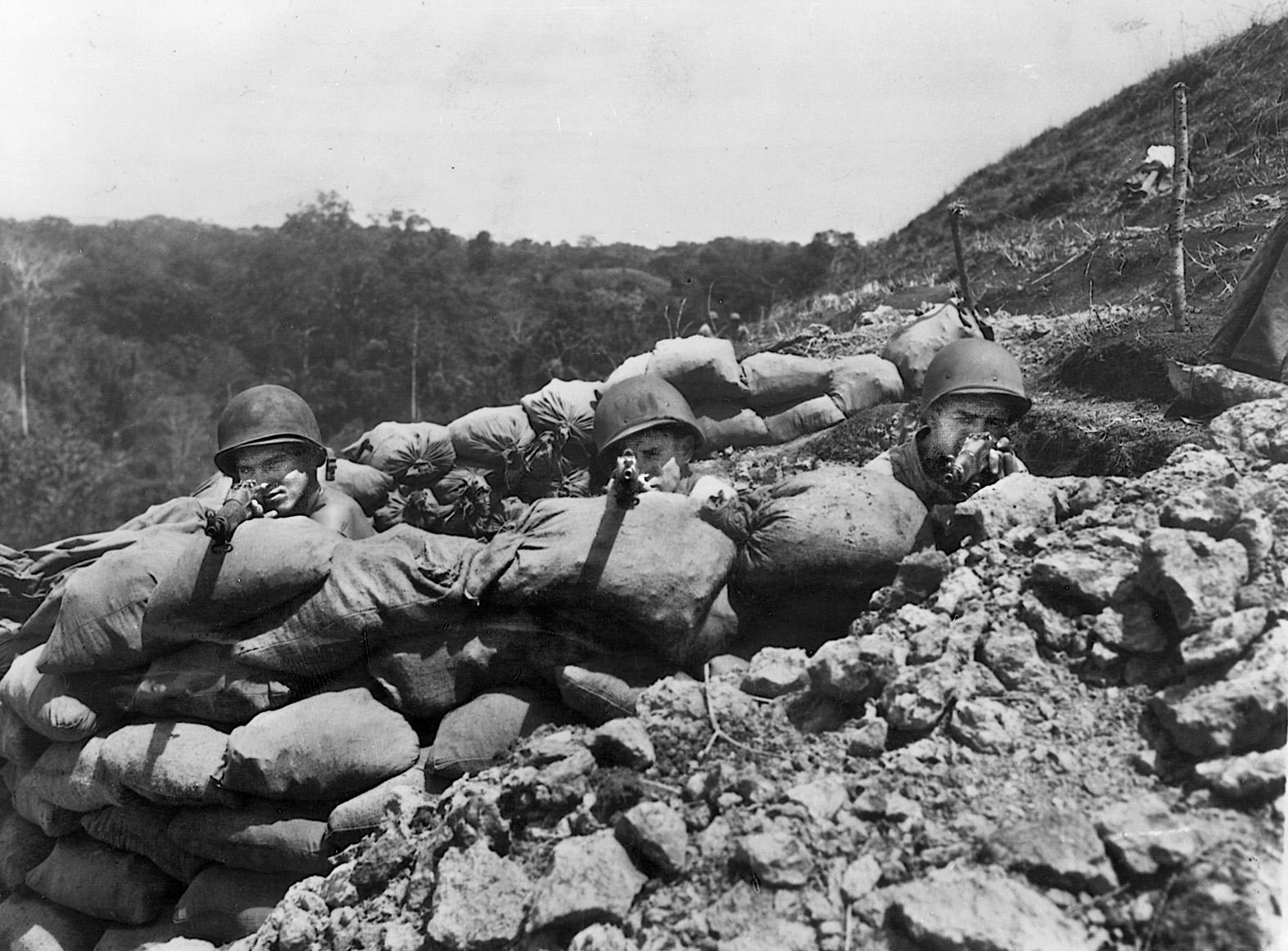

The selection of Stilwell was, in the short term, a sound one. He endured the defeat in Burma and personal hardship in fleeing headlong through the jungle. This afforded him the mantle of a hero and was an inspiration to the Allies.

Over the long haul, however, Stilwell’s disillusionment with the Nationalist/Koumintang leadership led to his undermining of its position relating to the developing Communist threat. Stilwell’s limited diplomatic aplomb was a negative in the overall scheme of things.

Of course, in reality, the Southeast Asia Theater was much like the Aleutians: far from the principal fighting fronts, fraught with difficulties not easily overcome with available resources, and best left as quiet as possible until the struggles in other regions determined the outcome of the war. For that purpose, General Stilwell’s military skills were irrelevant. Without the ability to have a serious impact on the outcome of the war or a strategic vision with which to plan for events after the war, all of his stress and strain beyond keeping China going in the effort against Japan were just a spinning of wheels.

Stilwell’s growing bitterness and anger, which bubbles over in his papers, demonstrate a misanthropic disposition. He was not able to accept the many disappointments, which were almost inevitable from the inconsistent and even contradictory objectives, methods, and tools with which he was provided.

Perhaps a contributing factor, at least, in Stilwell’s deteriorating morale was the early impact of his cancer, which, not long after his return to the United States, was discovered to be in an advanced stage and caused his death in October 1946.

The fruit of one general’s recalcitrance and wriggling out of the Southeast Asia assignment and of another general’s acceptance of the burden was the establishment of the China-Burma-India Theater, which supported the maintenance of China as a partner in the struggle against Japan.

To that extent, success flowed from the decisions that were made. In effect, the incident cleared away two persons who might have blocked the path of Eisenhower, the brigadier general in War Plans destined to have such a great influence on American and world history for years to come.

Bruce Graham, of Winter Park, Florida, is a graduate of Fordham Law School and is retired from positions as an administrative law judge and a part-time misdemeanor judge in Iowa.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments