By Pat McTaggart

“Where is Steiner?” Adolf Hitler demanded as his Thousand Year Reich crumbled around him in April 1945. “Is he attacking yet?” The Steiner in question was SS Obergruppenführerund General der Waffen SS Felix Steiner, a man who had served in Hitler’s Black Guard since 1935.

Steiner was born in Ebenrode, East Prussia, on May 23, 1896. His family had been Austrian in origin, but had emigrated from Salzburg to Prussia in 1731. The son of a middle-class grammar-school teacher, Felix would have many options to make a decent living in the Kaiser’s Reich when he grew to manhood. At age 17, he decided that he wanted a career in the Army, and in March 1914 he enlisted as a cadet officer in the 5th (East Prussian) Infantry Regiment von Bozen.

Felix Steiner’s Early Exposure to the Pain of War

He found that he was well suited to army life, throwing himself into the training and lectures that would eventually make him an officer. That training was short lived, however, as the war clouds that had been gathering over Europe burst that August.

With the outbreak of war, Felix Steiner’s regiment was sent to the Russian border to deal with an expected Russian invasion. In the cold, damp months that followed, he saw the face of war on a very personal level as his regiment fought in the Masurian Lakes area. He was severely wounded in November, earning him a stay in the hospital as well as the Iron Cross, Second Class. On January 27, 1915, he received a promotion to second lieutenant while still on convalescent leave.

After months of recovery, the young officer was posted to Fortress Machine Gun Detachment 1. In 1916, he was transferred to the Kurland (Lithuanian) Front as a company commander in Machine Gun Sharpshooter Detachment Ober-Ost 46. Throughout 1916 and 1917, he led his men in battles around the Düna River and Riga, where he earned the Iron Cross, First Class.

Carnage on the Western Front

In the spring of 1918, Steiner’s unit was sent to the slaughterhouse in the west. The carnage that he saw in Flanders and France left a deep impression on him. Both the Germans and the Allies had wasted the cream of their armies in four years of trench warfare, and the recruits that now bore the brunt of the fighting were little more than cannon fodder, sullenly waiting for another charge that would more than likely end their young lives.

The German Army’s offensive in the fall of 1918 was its last gasp. Although successful at first, the armies of the Kaiser soon ran into an Allied defense that slowed and then stopped any hope for victory. In those final battles, Steiner noticed that the Sturmtruppen (assault troops), which were special groups used to breach the Allied lines, enjoyed both success and a camaraderie that was not found in the Regular Army units. Impressed by their boldness and high level of training, Felix Steiner would carry the memory of their final battles into the postwar period.

A Lack of Direction at War’s End

On October 10, 1918, the battle-hardened Steiner was promoted to first lieutenant. Two months later the war was over and he was demobilized. Like many of his comrades, the 21-year-old former officer felt lost and betrayed in the new democratic Germany. In January 1919, he joined a volunteer corps to fight against Communist elements on the eastern border. His experience during the war made him a natural leader, and he was soon in command of a unit fighting in the area around Memel, on the Lithuanian frontier.

Returning to Germany, Steiner found a place in the 100,000-man Reichswehr, the postwar German Army. He joined the 1st Infantry Regiment in 1921. For the next few years, he served in several positions, including duty with the General Staff. Promoted to captain on December 1, 1927, he became adjutant to the 1st Ostpreussischen Infanterie Regiment headquartered in Königsberg. In 1932, he was leading a company of the regiment, using the skills that he had learned during the war to train a new generation of German soldiers.

Steiner left the regiment in 1933 and was used for special assignments by the training department of the newly formed Wehrmacht. In December 1933, he retired from the army with the rank of major, and the following year he became a training adviser.

Felix Steiner Joins Precursor To Waffen SS

It was a time of expansion for the German Army, and Steiner immersed himself in his new job wholeheartedly. As time wore on, however, he found himself longing for a greater challenge. On March 16, 1935, he joined the SS Verfügungstruppe(V-Truppe), which would eventually become the Waffen (armed) SS.

Steiner was appointed commander of the 3rd Batallion/SS Standarte “Deutschland” with the rank of OberSturmbannführer (Lt. Col.). At the time, the V-Truppe was little more than a ceremonial guard with little or no military training. Steiner saw the V-Truppe as fertile ground for building a new military force within Germany, outside of the general armed forces. To accomplish this, he and other like-minded ex-army officers such as Paul Hausser set about the ambitious project of turning their men into an elite fighting unit.

“I must admit that we were a little aggressive in our desire to prove our theories in the military field and further our own ambitions,” he later wrote. “By the mid-1930s we had managed to install ourselves as commanders of these cadres, the embryo SS combat units who were at that time little more than novices, very keen but without any military training at all.”

New and Radical Methods To Mold Elite Troops

Steiner was determined to turn his men into the finest soldiers in Europe, if not the world. To do this, he abandoned many time-honored traditions of the German Army, first as battalion commander and later as commander of the Deutschland, which he took over in 1936.

Drawing on his front-line experiences of World War I, he worked with his 3rd Battalion, using methods that shocked many of the older, more traditional officers. One of the first things he did was to relegate the barracks square drill to a position of secondary importance. His primary concern was to create a hardened fighting force, so he stressed athletics and sports as a way to build up the body for the rigors of warfare.

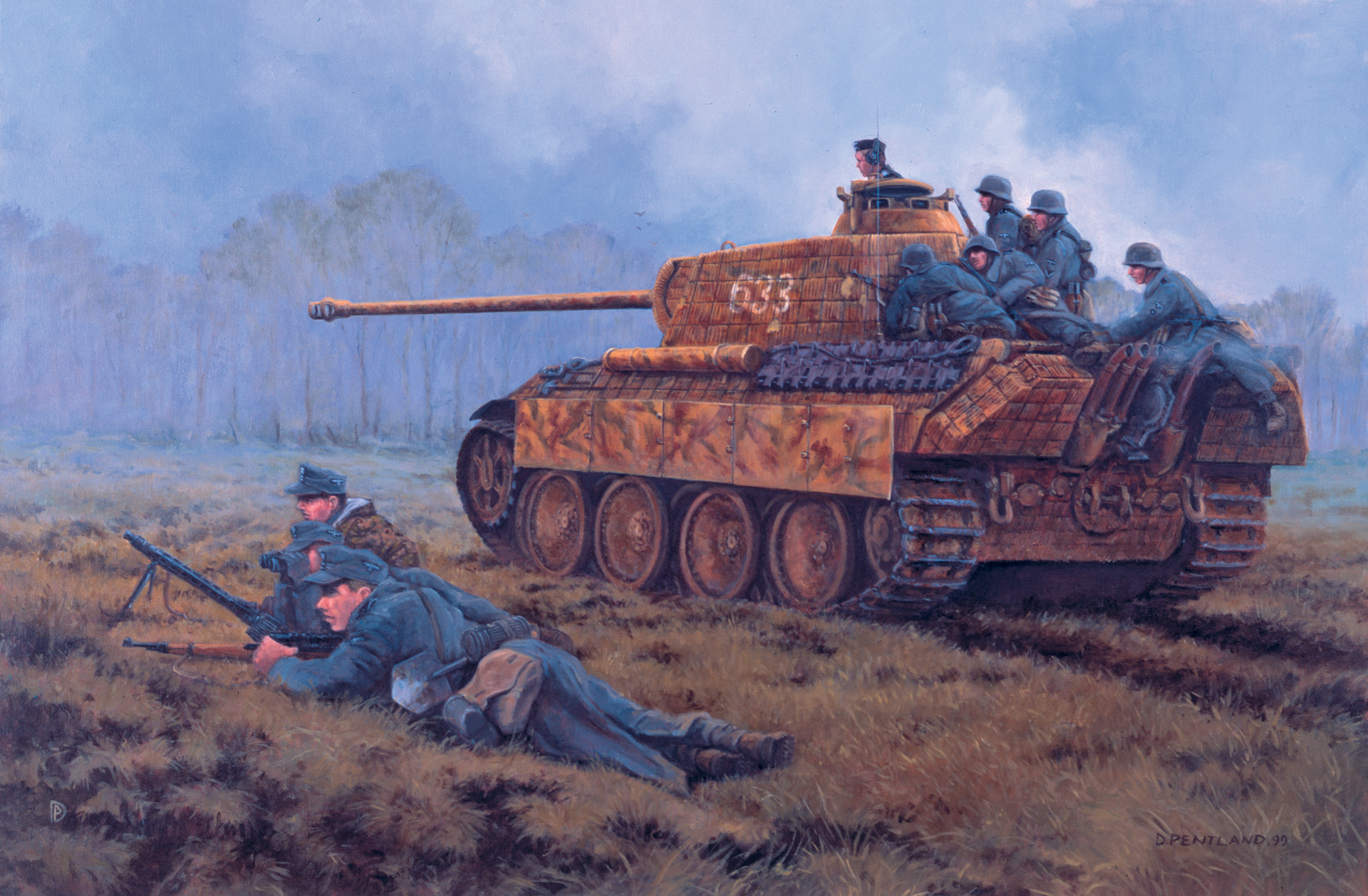

Recalling the tactics of the Sturmtruppen during the final battles of the Great War, Steiner equipped his men with lighter weapons (sub-machine guns, hand grenades, pistols, and explosive charges) instead of the trusted Mauser rifle. He also introduced a camouflaged battledress to replace the basic field gray uniform and used live ammunition in his training exercises.

Class Barriers Torn Down To Build Trust

Another Felix Steiner innovation was the abolishment of the class system between officers and enlisted men. He knew full well that the hardships on the battlefield demanded an unquestioned trust between the two groups. Therefore, he broke down the traditional barriers that separated the men from their superiors by having them compete in sporting events as equals. The officers and enlisted men also shared the same mess area, and anyone aspiring to become an officer had to serve at least two years in the ranks before being accepted for officer training.

Steiner slowly transformed the Deutschland into a unit that impressed even senior army officers. His innovations soon found their way into other SS Standarte, including the LeibStandarte Adolf Hitler, the Führer’s bodyguard unit commanded by Hitler’s old friend Josef “Sepp” Dietrich.

After the war, Steiner wrote, “I believe we succeeded in producing a very fine type of young leader who was above all inculcated with the team spirit never taught in the German Army. Everyone in the SS units joined in activities together—the greater emphasis was always on team spirit and comradeship.… We intended to instill an unparalleled esprit de corps in our force that would mark it out as one of the finest ever assembled. In the main, I believe we achieved this objective, despite what some said about us and at times not without reason.”

Hitler Puts V-Truppe on Equal Status With Rest of Wehrmacht

On August 17, 1938, Adolf Hitler signed a decree recognizing the V-Truppe as a permanent force. The three Wehrmacht services (Army, Navy, and Air Force) had continued to look upon these “Asphalt Soldiers” as bastard children, but with the stroke of a pen, Hitler had elevated the V-Truppe to a more or less equal footing in the armed forces.

Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler saw the V-Truppe as an internal stabilizing force for the Nazi regime—one that would quell any popular uprising that might take place. Steiner, who had nothing but disdain for Himmler, continued to regard his men as the nucleus of a new army. The two men would have more than likely crossed swords had it not been for the outbreak of war. In August 1939, a few days before the invasion of Poland, Hitler issued an order placing units of the V-Truppe under the command of the army, securing for them a position as military fighting formations.

Steiner’s Deutschland went to Poland as part of Division Kempf, a semi-armored unit named for its commander. Before the Polish defenses at Mlawa, the regiment received its baptism of fire. The young SS officers and men ran into heavy resistance as they sought to drive the Poles from their trenches and bunkers. Army reinforcements were called in and, after three days of intense fighting, the Poles were finally forced to abandon their positions.

Felix Steiner and the SS Prove Their Mettle in Poland

Pushing forward toward Modlin and the Narew River, Steiner tried to seize the river crossing at Rozan ahead of the retreating Poles. As the Deutschland neared the crossing, it ran into a hornet’s nest of machine-gun and artillery fire. Supported by elements of the 7th Panzer Regiment, Steiner ordered an assault on the old Imperial Russian forts that guarded the town. After another fierce engagement, the river crossing was captured, unhinging the Narew defense line and opening the way to Warsaw from the north.

The rest of the short-lived Polish campaign saw Steiner and his men engaged in several other actions, culminating with the siege of the Modlin fortress, which capitulated on September 28. Several members of the Deutschland had distinguished themselves during the fighting, including Herbert Gille, Matthias Kleinheisterkamp, and Fritz Witt—all of whom would go on to lead divisions of the Waffen SS.

Felix Steiner had trained his men well, and his new methods had held Deutschland’s casualties down to 15 dead and 35 wounded, compared to much higher losses in the other units of the V-Truppe operating in Poland. In the eyes of Hitler and high-ranking members of the SS, the V-Truppe had proven itself in the field. Despite army resistance, an SS police division was formed in late September. On October 10, SS Gruppenführer (Lt. Gen.) Hausser began forming the motorized Verfügungstruppe Division(V Division), which would later be renamed Das Reich. Three regiments—Germania, Der Führer, and Steiner’s Deutschland—made up the division.

Himmler’s Praise Doesn’t Impress Steiner

The success of Deutschland in Poland caused Steiner’s star to rise in the eyes of Himmler. The Reichsführer had finally realized that having a militarized SS could further his own ambitions and that Steiner had been the key to that successful military transition. After the Polish campaign, Himmler heaped praise upon Steiner, but the East Prussian was not the least bit impressed. He still regarded his chief as an incompetent bumbler whose constant interference would hinder, rather than help, the growth of the Waffen SS.

Steiner was proud of his regiment’s success, but he knew that the next battle would not be long in coming. During the winter of 1939 to 1940, Deutschland was stationed near Würzburg, and later near Münster, but the troops had little time to savor the hospitality of those cities as they were constantly in the field, training and honing their skills. Steiner’s motto, “Sweat saves blood,” had served his men well in Poland, and he was not about to let them lose their fighting edge.

During the first week of May 1940, the regiment was transported to the western frontier with Holland. On May 10, Steiner led his men across the border as part of General der Artillerie Albert Wodrig’s XXVI Armeekorps. The unit breached Dutch defenses along the Wilhelmina Canal and began a march through the country that ended with the capture of Walcheren Island, south of Rotterdam, on May 17.

Pushing Into France

Deutschland and the rest of the V Division then turned south and fought their way through Belgium and into France. Advancing toward Dunkirk, the division ran into heavy British resistance in the Nieppe Forest. While the two other regiments of Hausser’s division were locked in the forest battle, Steiner’s regiment was sent on a flanking attack with the 3rd Panzer Division. Breaching the enemy line, elements of the panzer division were stopped by a strong British defense at Merville. Steiner turned his regiment to bypass the enemy strongpoints and managed to reach the Lys Canal, which was also heavily defended by the British. Nevertheless, he ordered an assault across the canal and established a bridgehead on the other side, making Deutschland the lead unit in that sector of the front.

The British, determined to dislodge the Germans, sent an armored group to force Deutschland back. In the action that followed, several tanks were destroyed by the young and sometimes foolhardy SS troopers. Men were crushed in their foxholes as they flung hand grenades, trying to disable the tank’s track mechanisms, while others were shot down trying to jump onto the vehicles to pry open the hatches and disable the crews with bullets or explosives. Salvation for the bridgehead came in the form of a tank-destroyer unit from the SS Totenkopf Division, which forced the surviving British to withdraw.

Reinforced V Division Readies For Final Battles

With the evacuation of Allied forces at Dunkirk, the V Division made ready for the final battles for France. Replacements had been sent from Germany to make good the losses suffered by Deutschland and her sister regiments, and on June 5 the division entered the fray.

In the series of battles that followed, Steiner led his men through the defenses of the Weygand Line and across the Aisne River, taking position after position in sharp assaults. After crossing the Marne, the unit swept on east of Paris, crossing the Seine northwest of Troyes. Although Paris had capitulated on June 14, the French continued to resist, and from June 16-18 Deutschland took part in a fierce battle near Chatillion in which it took an estimated 5,000 prisoners.

The fall of France found Steiner’s regiment on the demarcation line with the newly formed Vichy territory. For his part in the battle for the West, Steiner became one of the first three Waffen SS recipients of the Ritterkruez (Knight’s Cross) on August 15. The 32-year-old commander of his 1st Battalion, Fritz Witt, received the award on September 4.

Reward, Promotion and Rebuke For Brash Young SS Officer

With the end of the campaign, the V Division was sent to Holland to rest and refit. Himmler, anxious to reward his SS heroes, promoted Steiner to the rank of SS Brigadeführer und Generalmajor der Waffen SS on November 9. In spite of his promotion and his well-earned decorations, Steiner made no bones about his contempt for his boss. When Himmler heard that Steiner had referred to him as a “sleazy romantic,” Himmler rebuked him by saying, “You are my most insubordinate general.” The Reichsführer was also forced to send an aide to tell Steiner to keep his mouth shut after word reached him that the East Prussian had been vocally criticizing Hitler’s strategy during the campaign in the west.

Many men would have landed in a concentration camp for Steiner’s utterances, but circumstances demanded that Himmler keep his outspoken and insubordinate general. The Waffen SS was growing, and commanders such as Steiner were needed to turn the raw recruits into fighting men.

Steiner Receives Expanded Division and Commences Training

In an order dated December 1, 1940, the SS regiments Nordland (which had contingents of Norwegians and Danes), Westland (Flemish and Dutch), and Germania were brought together to form a new division with Steiner as its commander. On January 1, 1941, the unit was officially designated the SS Division Wiking.

Steiner wasted little time in beginning the training of his new division. His three regimental commanders, Hilmar Wäckerle (Westland), Reichsritter von Oberkamp (Germania), and Fritz von Scholz (Nordland), knew what Steiner expected of them, and the division soon began to take shape as a multinational fighting force. His artillery commander, Herbert-Otto Gille, was a trusted friend from the old V Division. He, too, was an ex-army officer who shared many of his commander’s opinions, including his disdain of Himmler.

Steiner was faced with turning this multi-national division into a battle-ready unit within a matter of months. He also had to contend with the language and cultural differences that the young volunteers brought with them. After some initial difficulties with some of the more arrogant German training officers and NCOs (Steiner soon weeded them out), the men were soon doing as well or better than their German counterparts in the division.

Wiking Division Begins Fateful Campaign on Eastern Front

At the beginning of June, Steiner was ordered to transport the division to Silesia. It then marched into Poland and settled into camouflaged positions near Lublin. On June 22, as part of Generaloberst Ewald von Kleist’s Panzergruppe 1, Wiking crossed the Russian border and began what was to be a four-year struggle to the death against the Red Army.

By early July, the division had fought its way to Tarnopol, earning the respect of both friend and foe. Von Kleist praised the formation and its commander for its fighting ability and esprit de corps. A captured Soviet commander, Maj. Gen. Artemenko, told his captors that Wiking has shown greater fortitude than any unit on either side and that the Soviets “breathed a sigh of relief” when Steiner’s men were relieved in a sector by Regular Army units.

Steiner kept the division moving, crossing the Dnieper River and heading toward Dnepropetrovsk. Losses began to mount as the Soviets hit back, trying to stop the Germans, but by early October the division was still on the move across the desolate steppes east of the Dnieper. In October, however, the rains started to fall in southern Russia, turning the rich soil into a quagmire that made movement all but impossible. In November, the division repulsed several Soviet attacks that were a prelude to Stalin’s planned winter offensive.

Soviets Launch Winter Offensive; Steiner’s Division Holds

The men were exhausted, and replacements were needed by all regiments of the division. Westland, for example, had suffered a casualty rate of 50 percent killed, wounded, or missing from July 1 to November 30. Steiner saw little choice but to go on the defensive for the winter. During the next few months, Steiner’s men held positions on the Mius River against several major Soviet attacks, bleeding the Russians white as they tried to force their way through Wiking defenses.

Finally, the Soviet offensive ground to a halt. Replacements arrived to flesh out the division, and Steiner seemed to be everywhere at once, watching his regiments train and giving advice on how to improve their assault tactics. A panzer detachment, commanded by Sturmbannführer (Major) Johannes Mühlenkamp, was assigned to the division, giving it the armored muscle it would need for the coming summer offensive.

In July, Wiking took part in the storming of Rostov and then set off across the steppes toward the Caucasus. By the end of September the division had reached the southern European land bridge with Asia. Crossing the Terek River, Steiner and his men became embroiled in fighting for control of the rugged, mountainous terrain near Mosdok and Alagir. The fighting continued until late December, when the division was ordered out of the line for rest and to receive replacements.

A Promotion and New Assignment Received at Wolf’s Lair

On December 23, 1942, Steiner was awarded the oak leaves to the Ritterkreuz for his successes with the Wiking Division. The formal presentation took place on February 5, 1943, at Hitler’s Wolfsschanze (Wolf’s Lair) headquarters near Rastenberg, East Prussia. Sometime before the presentation, he learned that his days with Wiking were numbered and that he had been selected to form a new SS panzer corps.

Steiner must have been both puzzled and amused upon learning of his elevation to corps commander. His time with Wiking had done little to endear him to Himmler, who had reprimanded him on several occasions for signing his orders “Generalleutnant Steiner” instead of using his SS rank. He had also been admonished for criticizing the Reich’s policy of treating the Russians as subhumans and for greeting his men with a half-hearted “Heil” instead of the standard “Heil Hitler.”

Despite his growing reputation as a general who traveled his own course, Steiner took command of the new III(Germanisches) SS Panzerkorps, which was supposed to be built around the Wiking and Nordland SS divisions. In reality, the corps was given whatever troops were on hand, including army and Luftwaffe units.

Cracks Begin To Show

Throughout the summer and fall, Steiner worked to turn his corps into a cohesive fighting unit. His SS units’ morale was still high, but the army units that passed through his command were beginning to show the strain of the horrors of the Eastern Front. In June, an old friend, Friedrich Graf von der Schulenburg, visited with Steiner, who was due to be promoted to Obergruppenführer(Lt. Gen.) on July 1.

Schulenburg, a rabid anti-Nazi, and Steiner talked about the days when they had served together in the 1st Infantry Regiment and then switched to the current situation on the Eastern Front. As Schulenburg left, he told Steiner, “We shall have to kill Hitler before he ruins Germany.” The SS general remained silent, troubled by his friend’s parting words.

Combat for Steiner’s corps in the summer and fall consisted of actions against the partisan forces in Yugoslavia. In late November, the corps was ordered to the Front and began a long trip north to the Orianenbaum Front of Heeresgruppe (Army Group) Nord. It was a corps in name only, consisting of the Nordland Division and SS Polezei (Police) Regiment 14. Arriving at the front, the poorly trained and inadequately equipped 9th and 10th Luftwaffe field divisions were added to the corps, as was the 4th SS BrigadeNederland. Steiner hoped that he would have time to train his lackluster Luftwaffe units, but the Soviets had other ideas.

Soviets Rain Hell Fire Upon German Forces

On the night of January 13, the Soviets inside the Orianenbaum Pocket unleashed an artillery barrage of devastating proportions. More than 100,000 shells fell on the corps’ positions. The barrage was followed by an attack from the pocket by the Soviet 2nd Shock Army. Meanwhile, around Leningrad the Russians attacked German forces laying siege to the city with 42 Red Army infantry divisions and nine tank corps.

In Steiner’s sector, the 10th Luftwaffe Field Division disintegrated under the initial onslaught. The 9th soon followed, and Soviet tanks and infantry were soon in open country, hoping to encircle Steiner’s corps and the rest of the German 18th Army. The battle was not all one-sided. The commander of Nordland’s Engineer Battalion, Fritz Bunse, and Hanns-Heinrich Lohmann, commander of the Norge Regiment, were awarded the Ritterkreuz for delaying the Russian advance. The 5th Kompanie of Nordland’s reconnaissance unit, commanded by Georg Langendorf, destroyed 48 of 54 Soviet tanks in a single engagement, stopping a Russian breakthrough and allowing other units of the division time to escape.

Germans Win Race To River and Establish Bridgehead

Although these actions slowed the Russian advance, Steiner knew that the entire Leningrad Front had been shattered and that the only hope of rescue for his corps lay behind the Narva River, some 150 miles to the west. It was a close thing, but Steiner’s men won the race to the river. The SS general immediately established a bridgehead on the eastern bank and placed his artillery and support units on the western bank in the city of Narva itself.

In the months that followed, the defenders inside the Narva bridgehead held out against overwhelming odds. Augmented by remnants of some army divisions and by the newly formed 20th Estonian SS Division, Steiner moved his units like a chessmaster, containing Soviet attacks on his flanks and on the bridgehead itself. He was finally forced to withdraw from the position in late July after the Soviet summer offensive against Heeresgruppe Mitte had unhinged the entire northern front.

During the retreat through the Baltic States, the 5th SS Wallonien and 6th SS Langemarck Brigades joined the corps, making it a true European entity comprising German, Flemish, Walloon, Estonian, Norwegian, Danish, and Dutch soldiers along with a few Swiss, Swedes, and Finns.

Another Trip To Wolf’s Lair Before Mounting Retreat

On August 10, Steiner was summoned once again to the Wolfsschanze, this time to receive the coveted swords to the Ritterkreuz. He became the 86th soldier of the German armed forces to receive the award. Returning to his corps, he continued to conduct a fighting withdrawal. He remained with the corps until October 30, when he turned over command to ObergruppenführerGeorg Keppler and returned to Germany for a well-deserved rest.

At the end of January 1945, Steiner was given the task of defending Pomerania. His new command, the 11th Army, was a conglomeration of depleted army and SS divisions that stood little chance of halting the Russian advance into Germany.

“Accept My Plan Or Relieve Me!”

In mid-February, he was ordered to attack Marshal Georgi Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front and continue an advance to a point near Küstrin, where the Warthe and Oder Rivers converged. Steiner received the order with a mixture of rage and incredulity. Bypassing the chain of command, he telephoned Generaloberst (Col. Gen.) Heinz Guderian, the army chief of staff, and argued against the attack. Steiner told Guderian that with only 50,000 men and 300 tanks the operation would be a suicide mission with no expected success. He said that a more limited attack, which would leave the 11th Army less vulnerable to a certain Soviet counterattack, would put him in a better position to fulfill his mission of defending Pomerania.

As the discussion grew more heated, Steiner shouted into the telephone, “Accept my plan or relieve me!” Guderian shouted back, “Have it your own way!” and then hung up.

The attack started on February 16 and pushed the Soviet 68th Army back about eight miles on the first day. The next day saw another push by Steiner’s army that left scores of Soviet tanks burning in its wake. Steiner’s attack forced Zhukov to divert two tank armies, which were headed toward Berlin, to meet the attack. These new enemy units stopped the 11th Army, forcing it back to its original positions.

Hitler Pins Last Hopes On Steiner

Steiner’s limited victory gave Adolf Hitler hope. With his armies crumbling around him, here was a general who could still fight. In the upcoming weeks, the Führer would once again call on Steiner when all hope seemed lost.

Steiner kept command of the 11th Army until early March, when he turned it over to Army General Walter Lucht. As the Russians continued to batter their way to Berlin, Generaloberst Gotthard Heinrici, commander of Heeresgruppe Weichsel (Army Group Vistula), charged with defending the capital’s approaches, gathered a meager armored reserve and put Steiner in charge of the unit.

On April 21, Hitler was listening to a situation report describing the worsening conditions around Berlin. Soviet artillery was within range of the city, and General der PanzertruppeHasso von Manteuffel’s 3rd Panzerarmee, the only effective blocking force left in front of Berlin, was in danger of being encircled. As Hitler listened, Steiner’s armored unit was mentioned in passing. The name triggered an immediate response in Hitler, who was soon planning another fanciful mission for the SS general. This time, Steiner was ordered to attack and shatter Zhukov’s spearhead, which would prevent von Manteuffel from being encircled and would save Berlin at the same time. His command, now designated Armeegruppe Steiner, consisted of about 10,000 exhausted troops and a mere handful of tanks.

Plan To Eliminate Hitler Foiled By Bunker Retreat

For Steiner, the order seemed nothing short of lunacy. He had become more and more disillusioned with Hitler and his Reich since his conversation with von Schulenburg in the summer of 1943. Some weeks after that conversation, Steiner and Oberführer (no U.S. equivalent rank) Joachim Ziegler (his chief of staff) met with anti-Nazi elements and discussed arresting Hitler—a plan that never developed. Only a few days before receiving Hitler’s latest order, another plot was hatched by Steiner and Obergruppenführers Richard Hildebrandt and Curt von Gottberg. They planned to murder Hitler and end the war before Germany was totally destroyed, but by that time the Führer had already retreated to the relative safety of his Berlin bunker.

Hitler now waited for the attack, and Steiner did nothing. Time after time, Hitler asked his staff how the offensive was proceeding. When he found out the truth, he flew into a blind rage, sending Heinrici and Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel to Steiner’s headquarters to force him to attack.

Steiner remained firm. “I won’t do it,” he said. “This attack is nonsense—murder. Do what you want to me.”

Steiner Remains In Command and Saves Troops From Soviets

It was not until April 27 that Hitler finally gave up on Steiner. He ordered him to be relieved, but the SS general persuaded his replacement to leave him in command. It was Steiner’s final snub to the leader that he had once so gladly served. A few days later, Hitler was dead. During the final week of the war, Steiner led his unit to the west, surrendering to the Americans and saving his men from Soviet labor camps. He remained in captivity until April 27, 1948.

In the postwar years, Steiner wrote two books, The Army of Outlaws and The Volunteers, in which he described his wartime experiences. He also wrote From Clausewitz to Bulganin, a study in military history. He was active within the Waffen SS Veteran’s Association (HIAG) and kept in touch with many of his wartime comrades, attending several divisional reunions.

Trying to Set The Record Straight

Writing after the war, Steiner sought to defend his men and the Waffen SS organization. “A great deal of misunderstanding and misconception came about as to the role of SS troops, and I refer not only to other countries, but at home … let it be said that many thousands of young Germans fought and died for their country, not because of some fanatical blind faith in their Führer, but simply through patriotism. It would be naïve of me to suggest that they did not in many cases have faith in Hitler, they did, but then they did not know the ‘nature of the beast.’ By the time they learnt, it was too late.”

Steiner’s last years were spent in Munich, where he enjoyed meeting with a small company of close friends and wartime associates. On May 16, 1966, the former SS general died of heart failure. His funeral was attended by hundreds of his men who came from all over Europe to pay their last respects.

Did Felix Steiner have a wife and a son named Herbert, who lived in Syracuse, N.Y. in the 50’s and 60’s?

I knew Herbert very well. He had Hitler’s tapes, privately taped and massive amounts of pictures of his father, who knew Hitler well.

Herbert moved back to Germany in the 60’s and worked for a huge department store.

Anyone about Herbert Steiner?