By Eric Hammel

The popular conception of the struggle in the air over northern Europe during World War II is of squadrons of sleek fighters racing over the German heartland to protect contrailed streams of lumbering bombers stretching beyond sight. This is as it was during the second half of America’s air war against Germany, but it was as far from the truth as it is possible to get at the start of that great aerial crusade. It took until late 1943—nearly two years after the United States entered World War II—before the United Kingdom-based Eighth Air Force mounted strategically significant bombing missions against targets in occupied northern Europe. The fault for this lay partly in the availability and slow development of the equipment, but it is also a fact that the two men at the top of the Eighth Air Force command structure stubbornly clung to old and discredited theories that stunted the effectiveness of the strategic-bombing effort and cost thousands of their countrymen their freedom or their lives.

In the beginning, the fighter was a short-legged creature whose role of protecting the bombers was eclipsed by its role of guarding friendly territory and installations. The difference, which is crucial, was the product of technology—range and the power of aircraft engines—and intellect. Until late 1943, surprisingly late in the war, the use of the fighter as an offensive weapon was stunted by the defensive mind-set of the “pursuit” acolytes of the interwar decades.

The pursuit airplane had evolved over the fixed battlefields of Western Europe during World War I. Pursuit aircraft had been developed to prevent enemy reconnaissance airplanes from overflying friendly lines and to protect friendly observation airplanes from enemy pursuits while the observers overflew enemy lines. The pursuit was conceived as a tactical and a defensive weapon, and it was limited to these roles both by conception and by the technologies of the day.

The Army Air Corps

Between the world wars, the development of American pursuit aircraft was hobbled by budgetary restrictions that for many years slowed or obviated altogether the creation of new technologies or even methodical experimentation with new tactics. The U.S. Marine Corps did advance the use of the single-engine pursuit as a nascent close-support weapon to bolster the infantry, but the interests of various intra-Army constituencies prevented similar advances in what had come to be called the Army Air Corps. To the degree that it developed at all, the Air Corps saw increasingly heavy and longer ranged bombers in its future. And, as the limited available research-and-development dollars were expended on speedier bombers, the pursuits of the day were increasingly outranged and outrun.

Inevitably, American bombers of the late 1930s were designed to be “self-defending” because they could fly much farther and at least somewhat faster than could the pursuits of the day. The pursuits, which were being developed at a much slower pace, were relegated to a point-defense role—guarding cities, industrial targets, and air bases. When World War II began, the Air Corps—shortly to be renamed the Army Air Forces—was divided into two distinct combat arms, fighters and bombers. And, by virtue of the fighter’s stunted development, there appeared little chance that the two would spend much time working together.

As soon as the Army Air Corps was pulled into World War II it became focused on the defense of American coastal cities, several Caribbean islands, bases in Greenland and Iceland, and on the strategically indispensable Panama Canal. There were few airplanes of any type to devote to these defensive missions, and those that were deployed defensively also had to serve as on-the-job trainers for hundreds of the raw young pilots emerging from the Air Forces’ burgeoning flight schools.

Through the first half of 1942, all of the very few pilots and airplanes that could be spared from the defense of the U.S. coasts and sea lanes were rushed to defend Australia and the South Pacific. Dozens of precious airplanes and pilots were lost in the pathetic defense of Java, in the Netherlands East Indies, and many more were lost in the early defensive battles around Port Moresby, New Guinea, but Army Air Forces’ training commands were able to catch up with combat and training losses as well as with the heavy burden imposed by the formation of new fighter, bomber, and other-type groups. And better fighters with a higher probability of survival began to reach operational air groups.

Committing to American Air Power

Fortunately, the United States could afford to be a bit late off the mark in her war against Germany. German efforts in 1940 to bring Great Britain to her knees all had failed miserably and, by the end of 1941, the bulk of Germany’s air and land forces were mired in a frightful war of attrition deep inside Russia. The British had the situation in northern Europe reasonably well in hand, though they would have collapsed had not vast infusions of weapons and supplies from the United States sustained them. British forces in Egypt and Libya were teetering on the edge of defeat, but there was little the United States would be able to do for many months to influence the outcome—assuming the British held on that long.

So, while the Army Air Forces devoted the bulk of its limited expendable resources to defensive measures against Japan, new air groups were created, and new and better combat aircraft began rolling off newly created assembly lines. Finally, in the spring of 1942, it was decided in high Army Air Forces’ circles to commit American air power to northern Europe. At first, the commitment would be little more than a meager show of force masking an advanced combat-training program overseen by the Royal Air Force (RAF). Only later, when training bases and factories in the United States had caught up with the planning, would the U.S. Army Air Forces take on a strategic air campaign against the German industrial heartland.

Brigadier General Ira Eaker arrived in England on February 20, 1942 to establish the headquarters of the new VIII Bomber Command. He opened his headquarters at High Wycombe, England on February 23, 1942, but the VIII Bomber Command had no combat airplanes to its name; they would not be available for several months. Rather, it fell to Eaker to argue with his British hosts in favor of an independent role for the forthcoming Army Air Forces in Europe. The RAF and the British government wanted America’s commitment to the air war in Europe to be subordinate to or an adjunct of the British Theatre air war. The Americans, however, felt they deserved an independent role, and it was Eaker’s job to win the British over to this viewpoint.

The American notion was strongly bolstered—in argument, at least—by the fact that the Army Air Forces had developed over many years a theoretical strategic air doctrine that was quite different from the RAF’s experience-based strategic doctrine. The Americans favored and had equipped their bomber force to wage a precision daylight-bombing campaign against industrial targets hundreds of miles inside enemy territory. The RAF was the only other air force in the world that had developed long-range, four-engine, heavy bombers, but its doctrine—the result of bloody experiences early in the war—favored “area” bombing at night. Doctrinal arguments aside, the British victims of the Nazi Blitz of 1940-1941 were less squeamish than their American Allies about bombing German civilians. Besides, the RAF had few long-range heavy bombers to its name, and thus felt it needed to co-opt the promised infusion of American heavies.

For the time being, Eaker’s arguments with the RAF hierarchy were moot. There would be no American air-combat units in the United Kingdom for several months, and then there would not be enough of them to make a dent in Hitler’s Fortress Europa for many more months.

A Symbolic Commitment between Allies

The first VIII Bomber Command unit to arrive in England—on May 10, 1942—was the 97th Heavy Bombardment Group, which was equipped with Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress four-engine heavy bombers. This was a symbolic commitment, for the 97th had been activated in February 1942 and thus had not had time to be adequately trained to fly combat missions over heavily defended European targets. It would be months before the 97th saw any live action.

Around the time the 97th Heavy Bombardment Group became the first nominal combat unit to join Eaker’s VIII Bomber Command, Brig. Gen. Frank “Monk” Hunter arrived in England to establish the headquarters of his VIII Fighter Command, also at High Wycombe. Unlike Eaker, Hunter, a rather flamboyant World War I ace, quickly came to terms with British beliefs and aspirations regarding the employment of forthcoming American fighter groups. The RAF had opted for powerful, short-range, point-defense fighters that could defend friendly air bases and attack nearby enemy air bases, and its doctrine appeared to have proven itself during the Battle of Britain and the Blitz. Hunter, who had spent most of his career arguing the point-defense case for the U.S. Army’s fighters, was eager to augment the British fighter plan.

On June 10, 1942 personnel of the U.S. Army Air Forces’ 31st Fighter Group arrived in England by ship. After being outfitted with British Spitfire fighters, the green American fighter group was to begin rigorous advanced combat training overseen by a number of the RAF’s leading Battle of Britain aces. As with the 97th Heavy Bombardment Group, the 31st Fighter Group was not expected to begin combat operations for several months.

On June 18, 1942 Maj. Gen. Carl Spaatz arrived in England to establish the headquarters of the Eighth Air Force at High Wycombe. Spaatz was one of the handful of Army Air Forces officers with the moral authority to win an independent role for American air units over the forceful arguments of Britain’s top military and political leaders. Leaving the training of pilots and aircrews to Eaker and Hunter, Spaatz set out on a political path to forge an independent role for American air units. It was Spaatz’s brief from his superiors to integrate and modulate the projected American daylight air offensive with—but not subordinate it to—Britain’s night-bombing effort.

The Army Air Forces’ first combat mission against a German-held target took place on July 4, 1942. Six American-manned RAF-owned Douglas A-20 light attack bombers accompanied six RAF-manned A-20s in an attack on several German airfields in the Netherlands. Two of the American A-20s were downed by flak, seven crewmen were killed and one was captured, two failed to reach the target, and a fifth A-20 was severely damaged. The U.S. Army Air Forces could not have asked for a less auspicious or more humiliating inauguration of what would become the greatest aerial offensive in the history of the world.

The very first U.S. Army Air Forces fighter mission over Occupied Europe took place on July 26, 1942. As part of their training syllabus, six 31st Fighter Group senior pilots joined an RAF fighter sweep to Gravelines, a French town on the English Channel. German fighters challenged the American and RAF Spitfires, and the 31st Fighter Group’s deputy commander was shot down and captured.

31st Fighter Group Joins the RAF for a “Big Show”

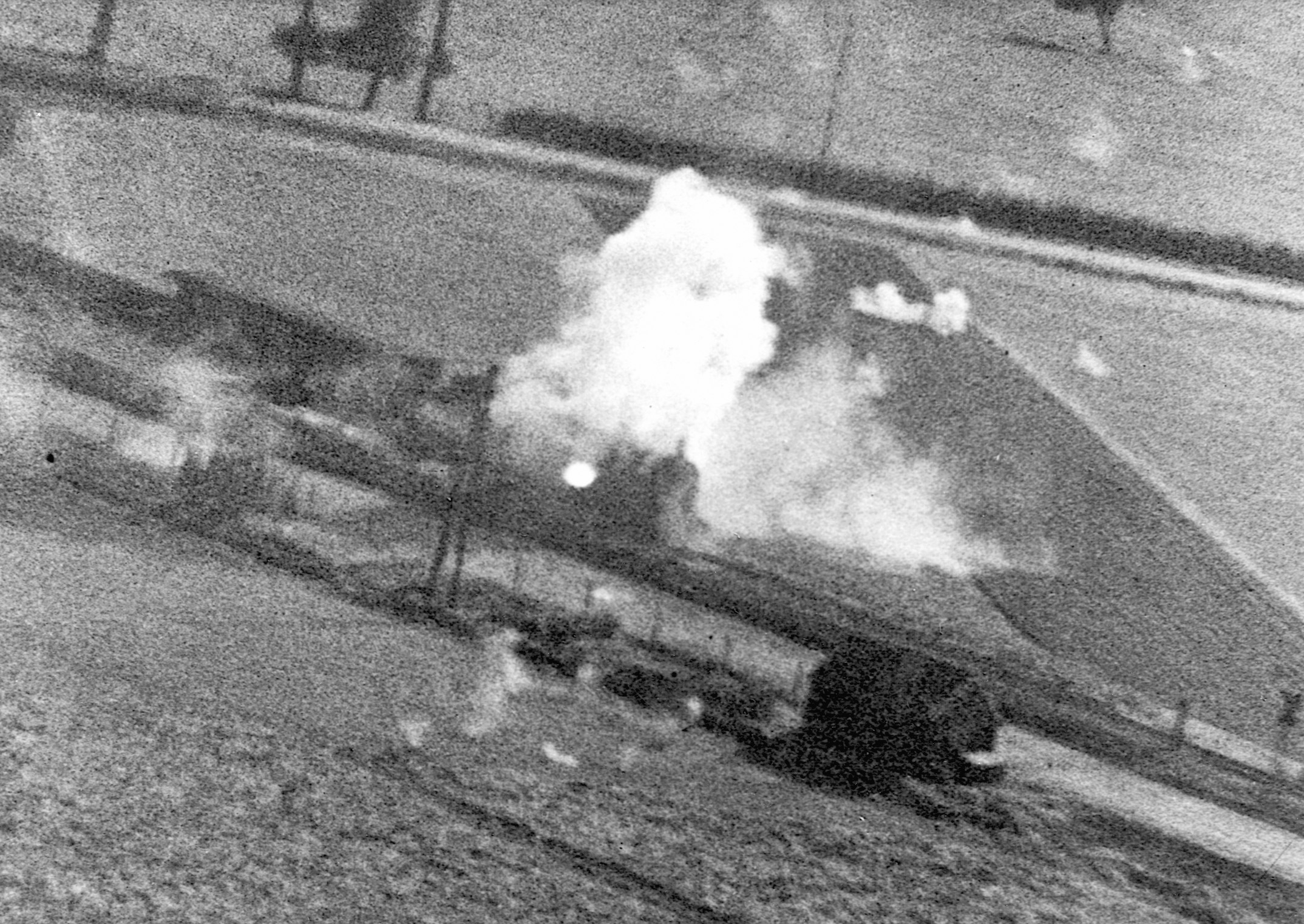

The 97th Heavy Bombardment Group had to wait until August 17, when a dozen B-17s, with General Eaker along as an observer, conducted an afternoon raid against railroad marshaling yards near Rouen, France, 35 miles from the English Channel. Escort for the bombers was provided by four RAF Spitfire squadrons. The results of the mission were negligible. One B-17 was damaged by a German fighter, but there were no losses and no injuries.

Two days later, on August 19, the entire 31st Fighter Group joined with the RAF for a “big show” across the Channel, the tragic invasion rehearsal at Dieppe. While completing four 12-plane missions over the beaches during the day, pilots from the 31st were officially awarded two confirmed and two probable air-to-air victories.

The 31st Fighter Group continued to fly fighter-sweep missions over coastal France, but it was awarded only one probable and no confirmed victories before it was withdrawn from combat operations in October to prepare for its upcoming role in the invasion of French Northwest Africa. Meanwhile, on September 12, 1942 the RAF’s three independent Eagle squadrons—fighter units composed entirely of American citizens who had enlisted in the Royal Air Force or Royal Canadian Air Force—were absorbed into the VIII Fighter Command as the new 4th Fighter Group.

Thanks to the withdrawal and diversion of other VIII Fighter Command groups for the North Africa Campaign, the 4th Fighter Group, which was outfitted with Spitfires, was the only operational American fighter unit in northern Europe until May 1943. Already endowed with experienced combat pilots, including a number of aces, from its RAF days, the 4th did about as well during its first six months of combat service as did RAF Spitfire units that took part in similar fighter-sweep missions. Between September 1942 and mid-April 1943, the 4th Fighter Group was awarded credit for 15 confirmed victories over France, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

The essence of the U.S. Army Air Forces campaign over northern Europe between October 1942 and the spring of 1943 was that, for practical purposes, there was no air campaign. The diversion of most of the small Eighth Air Force—fighters and bombers—to North Africa left the VIII Bomber Command and the VIII Fighter Command virtually no assets with which to wage any sort of offensive battle.

“The 4th Fighter Group was as Predatory a Fighter Unit as Ever Fought in a War”

From October 1942 until May 1943, only the 4th Fighter Group remained operational in the United Kingdom. The handful of other fighter groups that had reached the British Isles by October 1942 had been diverted or, in the case of the 78th Fighter Group, stripped of its airplanes, which were needed as replacements by groups in North Africa. Between early October 1942 and the end of April 1943, 4th Fighter Group pilots accounted for just 16 German airplanes. (Between mid-March and April 8, the 4th was withdrawn from combat so it could transition from Spitfires to Republic P-47 Thunderbolts. The group’s first aerial victories in the P-47—and the P-47’s first victories, ever—were scored on April 15 over the Belgian coast.)

As was to emerge in time, the paucity of aerial victories—even the paucity of aerial encounters—had less to do with the scarcity of American-manned fighters than it did with American fighter tactics. The 4th Fighter Group was as predatory a fighter unit as ever fought in a war. In better times, with better tactics, it became one of America’s premier fighter units. But during the period it flew as the only American fighter unit in operation in northern Europe—and for several months beyond—it attained negligible results because it was hobbled by idiotic tactics.

The immediate culprit was Maj. Gen. Monk Hunter, the commander of the VIII Fighter Command, but it must be said that Hunter was a product of his training and, to a degree, poor technology. Both of these factors obliged him and his eager fighter pilots—Hunter was eager, too—to work apart, virtually in a separate war, from the Eighth Air Force’s other combat arm, the VIII Bomber Command. Indeed, the doctrines that defined bomber and fighter operations were so far apart as to obviate direct cooperation.

The bombers had been built and the bomber crews had been trained to attack enemy targets without protection from fighters. Even as late as 1942, non-German air strategists honestly believed that wars could be won by bomber campaigns alone. Since the mid-1930s, Americans who accepted this outlook had developed what they called the self-defending bomber. That innovation, however, had more to do with the fighter technology of the 1930s; fighters of the day possessed neither the range nor the speed required to protect modern bombers. Fighter technology improved, but by mid-1942 the concept of the self-defending bomber had taken on a life of its own. It was believed that Germany could be bombed into submission by long-range self-defending bombers that were capable of flying—without fighter escort—to industrial targets anywhere in western or even central Europe. There was no offensive role for fighters.

As with most self-fulfilling prophecies, fact came to match belief. In 1942, American heavy bombers (and their British counterparts) had the range to strike targets in distant Berlin and beyond. The British had attempted daylight raids against Berlin early in the war, but they had been trounced by German fighter and antiaircraft-gun defenses. So they had switched to night “area” raids, nominally against industrial targets but, in reality, against whomever or whatever their bombs happened to strike.

Terror Bombings

The U.S. Army Air Forces, on the other hand, had developed qualms against “terror” bombings. And besides, America’s leading bomber enthusiasts believed strongly in the efficacy of both their precision daylight-bombing doctrine and their self-defending heavy bombers. Moreover, American fighters of the day, though powerful and powerfully armed, still lacked the range to accompany the bombers all the way to the nearest point in Germany and back.

Denied a role in escorting bombers to distant targets, and blinded by an outmoded and actually quite silly doctrine he had helped develop in the 1930s, Monk Hunter opted to send his meager fighter assets on “fighter sweeps” over those areas of France, Belgium, and the Netherlands that were within the meager operational range of the one fighter type that was then in his hands—the immensely heavy (7 ton) and short-ranged Republic P-47 Thunderbolt.

It must be said that it was not Hunter’s fault that he had inadequate airplanes (forget that there was only one group flying!), and he was not alone in his misperception of the role of fighters in World War II. The VIII Fighter Command’s failure to make a dent in the German fighter force—fewer than 20 confirmed victories in seven months—also goes to the role to which the Army Air Forces both aspired and had been relegated by 1942.

The key to every decision Allied commanders made in 1942 and 1943 was the projected invasion of France. At first, when the United States entered the war, it was hoped that the invasion would take place in mid-1943. By the late summer of 1942, however, the North Africa Campaign—and a huge number of other factors—made it clear that D-day was going to be delayed until mid-1944. As the first symbolic raids and sweeps were undertaken over northwestern Europe by Eighth Air Force fighter and bomber units in mid-1942, there were two full years to achieve preinvasion goals from the air. North Africa threw the margin into a cocked hat. If luck held, it would be mid-1943 before the strategic-bombing campaign could be resumed, and then only one year would be left for cracking the vast array of German objectives that would have to be overcome before the invasion could safely commence.

The primary role of American and British air power in Europe from mid-1942 until the invasion was to be the defeat of the Luftwaffe. Operation Pointblank, the specific plan by which the Allies were to accomplish this feat, was promulgated in May 1943 following acceptance of the common goal by the RAF and the U.S. Army Air Forces. The defeat of the Luftwaffe was of primary concern to the Allies because, at heart, it was constituted as a tactical ground-cooperation air force; it had been developed in its entirety to support German Army ground operations. Its bombers, for example, were light or medium models, and its bomber crews were trained to support ground troops at close or medium range. The Luftwaffe had no long-range capability—no strategic capability whatsoever; its role was tactical and, at most, operational. (This is precisely why the Luftwaffe alone was unable to overcome the RAF as a strategic objective during the Blitz; it was too lightly built to undertake a purely strategic mission.) As a superb tactical air force, however, the Luftwaffe was an enormous potential threat to an invasion fleet or a fledgling toehold on the soil of France.

Operation: Pointblank

In order to assure a safe landing by tens of thousands of Allied soldiers from thousands of ships, two things had to happen in the air before the invasion began—or could begin. The Luftwaffe had to be whittled down in strength and it had to be pushed as far back from the English Channel and North Sea coasts as possible. By forcing German tactical and operational air units to operate at the extremity of their ranges and in the smallest possible numbers—and only by doing so—could the mid-1944 invasion foreseen in mid-1942 be reasonably assured of success?

The goal of Operation Pointblank was to be accomplished in two ways: first, by simply shooting down German airplanes wherever they could be induced to fight and, second, by destroying Germany’s ability to build airplanes. To accomplish the latter, the destruction of the German aircraft industry and related targets, the British and Americans opened the Combined Bomber Offensive. The RAF would undertake night “area” bombing attacks against the German aircraft industry and the U.S. Army Air Forces would undertake daylight precision-bombing attacks against the same or similar targets.

Conceptually, the simultaneous Anglo-American program of aggressive (but, alas, short-range) fighter sweeps over the French, Belgian, and Dutch coasts was aimed at engaging the Luftwaffe fighter wings in a battle of attrition that over time would destroy the bulk of whatever reduced numbers of fighters the shattered German aircraft industry managed to produce. Further, by destroying German fighters, the Allies hoped to induce the German aircraft industry to switch over from the production of tactical bombers to the increased production of replacement fighters, which were less likely to hurt the invasion forces.

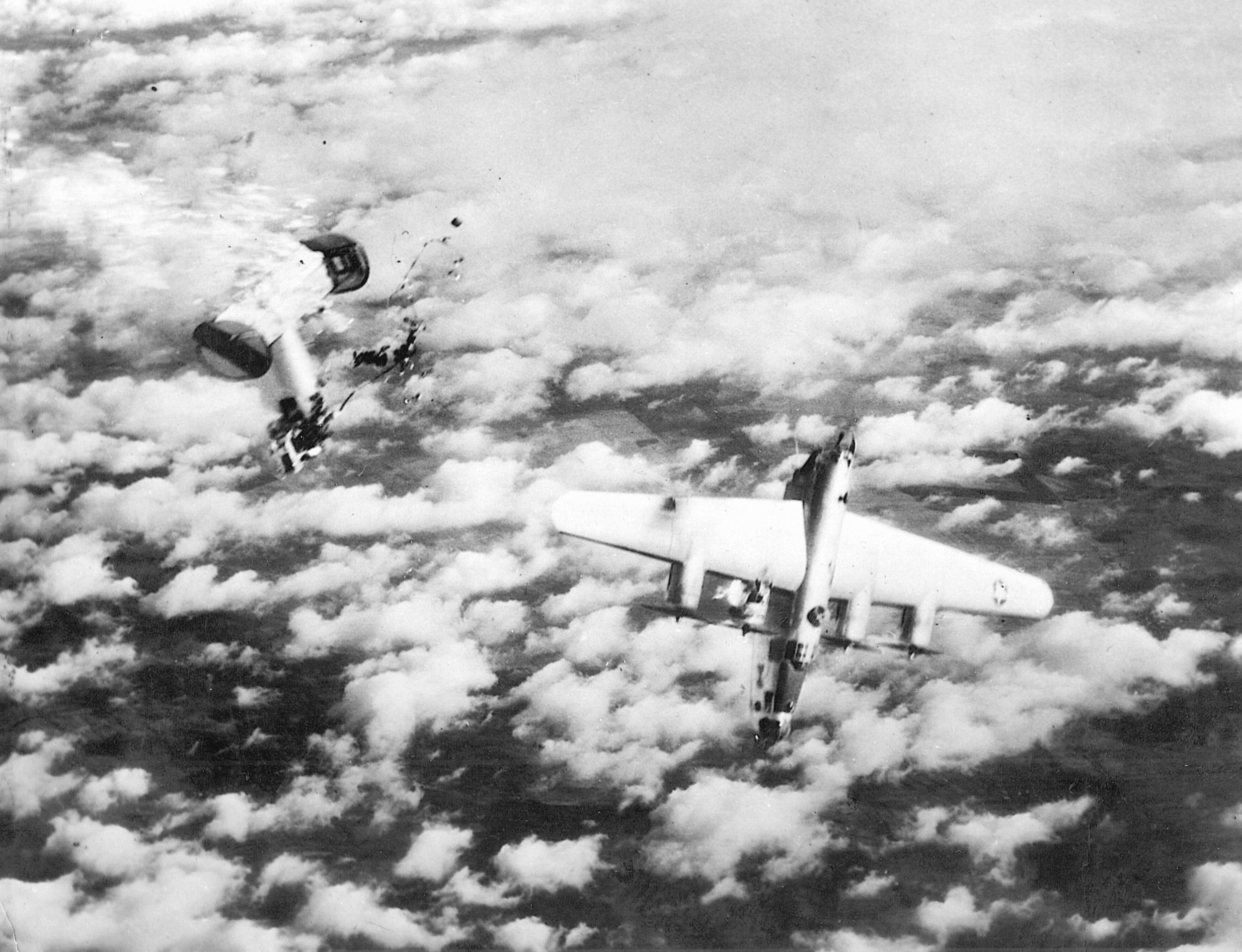

Sadly, while American fighters were being assiduously avoided by the crack Luftwaffe fighter units within their meager range, the “self-defending” daylight heavy-bomber groups charged with attacking strategic targets deeper inside France, the Netherlands, and northwestern Germany were being butchered. While the German fighters were sidestepping needless and avoidable attrition simply by ignoring the American fighter sweeps, the bombers were locked in a one-sided form of attrition that did not bode well for their survival.

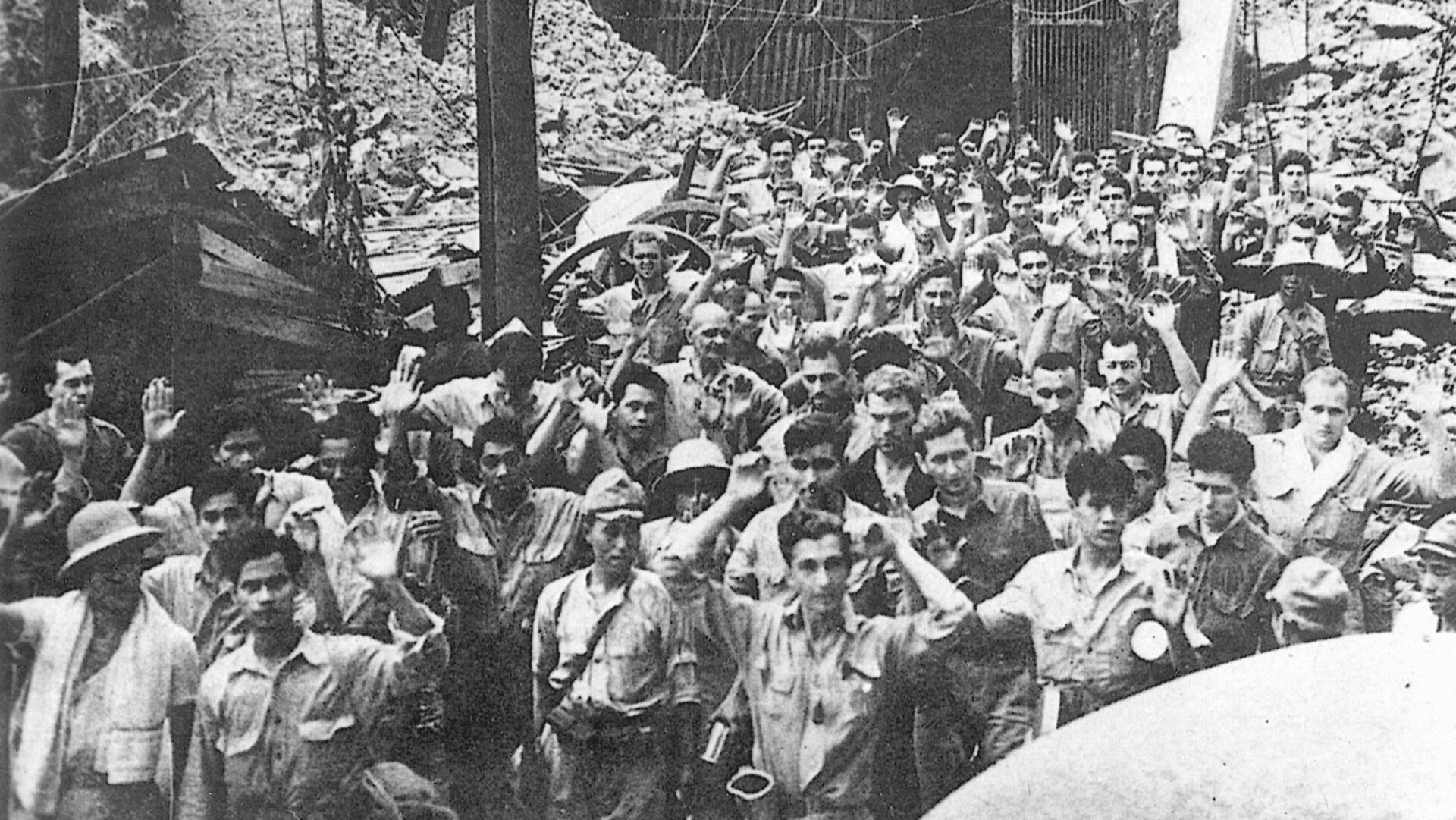

American Fighters Down 7 German Airplanes

Beginning in April 1943, the 4th Fighter Group’s new P-47 Thunderbolts were joined over the Channel and North Sea coasts by the Thunderbolts of the 78th Fighter Group—and another P-47 unit, the 56th Fighter Group, was in training in England. Despite the doubling of assets, the results remained abysmal. Meanwhile, losses of American heavy bombers continued to rise. Major General Ira Eaker, who had replaced Spaatz as Eighth Air Force commander when the latter went to North Africa, continued to champion the self-defending bomber, but he also alibied that there were not yet enough heavies available in northern Europe to make the strategy efficacious. However, in April 1943, after scores and then hundreds of unescorted “self-defending” bombers had fallen and thousands of American airmen had been killed or captured, Eaker finally did ask Monk Hunter to provide fighters for escort duty to the extremity of their range—going into the Continent (penetration), and coming out (withdrawal). The bombers would be on their own a good part of the way, but some protection at the margins apparently was deemed to be better than none at all. From May 4 onward, nearly all VIII Fighter Command sorties were devoted to escorting the bombers.

Seven German airplanes were downed by American fighters over northern Europe in May 1943, and 18 fell in June (seven in one day, June 22). Action during the first three weeks of July was sluggish, but an extremely aggressive new commander, Maj. Gen. Frederick Anderson, had just taken over the VIII Bomber Command on July 1, and he needed some time to make his aggressive new policies bite. On July 24, Anderson’s VIII Bomber Command opened “Blitz Week” with the first of hopefully daily appearances over Germany. Weather shut down bomber operations on one of seven consecutive planned mission days, but the other six days saw strikes aggregating just over a thousand bomber sorties against 15 targets all over northern and western Germany. Claims by bomber gunners were, as always, extravagant—330 victory credits were awarded—but there is no doubting that the German fighter forces were worn down somewhat, at least operationally, by the unrelenting appearances by the bombers.

The American escort fighters put in fewer claims by far, but the fact that their claims were closer to reality made them startling in their own right. In July 1943, American fighter combat produced 38 victory credits, of which 33—nine and 24, respectively—were scored during just two Blitz Week missions. Not coincidentally, the two missions in question were not only bomber-escort missions—they were the first nominally long-range bomber-escort missions ever flown by Eighth Air Force fighters.

On July 28, 1943 the 4th Fighter Group significantly increased the range of its P-47 fighters in an experiment with auxiliary fuel tanks. In so doing, its pilots took the Germans by surprise by flying much deeper into enemy territory than they ever had before. Nine German fighters were downed in what for the Germans was an unexpected melee around the American heavy-bomber stream. Two days later, on July 30, all three P-47 groups were able to use for the first time what the pilots referred to as “bathtub” belly tanks. The 115-gallon tanks—which were designed for use in long-distance ferry flights—were not pressurized, and they gave the pilots a lot of problems, but they did add 150 to 200 miles to each Thunderbolt’s operational range. Until then, the heavy fighter could barely reach Antwerp. With the tanks, the P-47s could make it well into the Netherlands. Thus, on July 30, when the target was the Focke-Wulf assembly plant in Kassel, Germany, more than two hundred VIII Bomber Command B-17s and B-24s took part in a mission that was covered to the greatest depth ever by friendly fighters.

An Incredible 24 Confirmed Victories in 1 Day

On the watershed July 30 mission, the 56th Fighter Group gave the bombers penetration support, the 78th Fighter Group provided early withdrawal support, and the 4th Fighter Group provided late withdrawal support. That meant that the 78th Fighter Group’s P-47s would be with the bombers quite soon after the heavies came off the target. The overall tactical plan was simple—protect the bombers and drive away the German fighters. The surprised German pilots either attempted to ignore the P-47s as they drove their fighters into the bomber stream, or they were sucked into dogfights at the expense of attacking their primary targets, the bombers.

There it was—24 confirmed victories in one day, on a single mission. The tactics and technology had changed, and American fighters had knocked down as many German airplanes in one mission as they had been able to in dozens of fighter-sweep and even escort missions in the preceding two months. In a short time, the large numbers of sturdy, reliable, streamlined, auxiliary fuel tanks that were shipped to or manufactured in England forever changed the tenor of the daytime air war in Europe. Indeed, the routine commitment of American long-range fighter escorts in mid-1943 changed the substance of war in the air as profoundly as the routine use of flimsy reconnaissance aircraft had transformed ground warfare in 1915.

The Germans knew there was no profit in attacking American fighters for the sake of engaging in dogfights that could go either way once they were joined. Fighters, per se, were no danger to the Third Reich. Bombers were. Bombers were a threat to everything—home, loved ones, and German morale and equanimity. American bombers, if they were allowed to get through to their targets, were an especial danger to the Luftwaffe itself, for they had shown a propensity to concentrate on the German industries from which German fighters and bombers emerged—ball bearings, machine tools, and airplane factories themselves. German fighters would never attack American or British fighters unless there was an overwhelming opportunity to win. But bombers had to be attacked, no matter where or when they appeared over Germany or her satellites. And, so, if the American fighter enthusiasts wanted to destroy the Luftwaffe at least in part through a strategy of attrition, they had to tie their fortunes to those of the bombers. To do that, better or much-improved fighters needed to emerge from the American industrial behemoth, better escort tactics needed to evolve, and better operational ranges needed to be achieved by the fighters.

The VIII Fighter Command’s three P-47 groups were credited with 58 German airplanes in August 1943, all of them during bomber-escort duty. In stark contrast, the American P-47s flew 373 fighter-sweep sorties over France on August 15 and did not see a single German airplane. Despite the numbers and mounting pressure from his superiors in Washington to adopt changes, Hunter continued to argue vehemently in favor of his discredited fighter-sweep tactic. In this, Hunter continued to be supported by the Eighth Air Force commander, Eaker, who remained a strong supporter in his own right of the self-defending bomber.

The ‘Aggressive’ William Kepner

Eaker was very close personally to the Army Air Forces chief, General Henry “Hap” Arnold, so his job was secure. But, though Hunter was also an old friend of Arnold’s, he had become an annoying relic. Hunter was replaced as head of the VIII Fighter Command on August 29 by Maj. Gen. William Kepner. A fighter pilot’s fighter pilot, Kepner was, in a word, aggressive. Moreover, his outlook was in full accord with the reality of the air war over northern Europe. He simply wanted to do whatever worked.

The VIII Fighter Command’s tally continued to rise, but the early escort tactic—stay with the bombers—quickly became ossified. Eaker eventually became an escort advocate, but next he refused the counsel of his escort commanders. As the range of their airplanes increased—especially after the introduction of the long-range Lockheed P-38 Lightning in late 1943 and the development of the North American P-51 Mustang—the fighter men thought they should range ahead of the bombers to break up Luftwaffe fighter formations before the bombers were molested—in other words, to go over to the offensive. Eaker, however, gave in to the wishes of his seriously demoralized bomber men, who wanted to see their escorts close up—an effective but nonetheless defensive mind-set. As a result, the fighters remained only marginally effective, and bombers and their crews continued to fall in record numbers.

At length, despite Eaker’s obstructionism, the Eighth Air Force forced the Luftwaffe to abandon its forward bases and defend the German heartland. This fit the preinvasion plan—move the German fighters far back from the invasion beaches—but the highly concentrated German defensive fighter effort (heavily augmented by improved antiaircraft protection) downed yet a higher percentage of bombers even while providing more fruitful hunting for the American fighters. The deadly spiral persisted until, at last, Eaker was replaced on January 6, 1944 by Maj. Gen. James Doolittle, who was brought in from the Mediterranean.

Doolittle and the new theater air commander, the redoubtable Carl Spaatz, immediately gave the Eighth Air Force fighters their offensive head. Thereafter, aggressive roving (“freelancing”) American fighters often dispersed the German fighters before the American bombers arrived on the scene. It was Bill Kepner and Fred Anderson, working together under Doolittle and Spaatz, who finally broke the back of the German fighter force, the one by shooting it down over Germany and the other by making a shambles of the German industrial base, especially the aircraft industry.

American Air Supremacy

The strategic air campaign leading up to the invasion was long and bloody. In the end, there was only one fair way to measure the success of Operation Pointblank and its many related phases and strategies: How much opposition was the Luftwaffe able to muster over the beaches and invasion fleet when Normandy was invaded on D-day, June 6, 1944?

On D-day itself two German fighters appeared over the invasion beaches. Two. No German fighters rose to challenge the hundreds of fighter-escorted transport aircraft that dropped three airborne divisions behind the Normandy beaches, and no German fighters or bombers—not one—attacked the invasion armada or landing force. On June 6, 26 German airplanes—fighters and light bombers—were destroyed over France by U.S. Army Air Forces fighters, but none of these came within sight of the Normandy coast. The Luftwaffe never meaningfully contested the invasion or any of the subsequent Allied land campaigns in Europe. By the time the invasion began, American bomber losses had dropped to negligible proportions, and the Luftwaffe had been virtually driven from the skies over its own homeland.

From mid-1944, thanks to the introduction of better fighters and the use of aggressive, realistic offensive fighter doctrines, American airmen attained—not the air superiority they sought, but—total air supremacy over the whole of western Europe.

This is a great article which finally and succinctly describes the actual history that occurred – instead of myth. This needs to become a book.

The whole air war over Germany was virtually a “make-it-up-as-you- go exercise. The fact that it finally worked is a testament to the vision of the leaders, even though not all of them performed as well as they might have.

But coming in, we had no precedent to follow, and not even the equipment to do it with, which we did ultimately receive, thanks to the brilliant minds of the plane designers, along with the input from the field, on what they needed to have, from experienced pilots who had been there, done that.

They sometimes made revisions to plane design in the field, fabricating many parts from scrap, and coming up with the multiple-gun forward firing setups, for example, such as the eight-gun .50 cal machine guns in the nose of the B-25s.

This, then, would filter back to the factories, where they would properly engineer the changes, and incorporate them into building into the design, from blueprint to finished product.

Briefly mentioned here was the failure of the Army Air Force to deploy more P-38 twin engine fighters in Europe earlier in the war despite their proven success in the Pacific. Had they arrived six months earlier, they could have been more effective and probably reduced the losses of bombers.

This is a good example of the axiom that the worst possible General is one who constantly changes his mind, never staying the course to find out if the strategy or operational doctrine is correct. The second worse General type is one who knows this and is sure he is correct and by doggedly following his strategy or doctrine he will win. Thus can ignore all proof to the contrary, Westmoreland from Vietnam being a similar example to the Bomber Mafia as listed in this very good article.