By John E. Spindler

Aboard one of two LCIs carrying French commandos approaching the Normandy coast, Lieutenant-Commander (Capitaine de Corvette) Philippe Kieffer looked at his watch. Its face showed 7:30 a.m. on what would be one of the most important days in history—June 6, 1944.

These 177 Frenchmen awaited their turn to storm Sword Beach as part of Operation Overlord. Four years removed from the fall of their country, French soldiers were finally returning to stay. Kieffer and his men would be the only contingent from France to fight on land that day. Part of Britain’s No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando unit, they served in Brigadier Lord Lovat’s 1st Special Service Brigade. For the invasion, Lovat placed these French combatants in the No. 4 Commando, led by French-speaking Lieutenant Colonel Robert Dawson.

Having sailed from England, the troops eagerly anticipated the moment they would reach the soil of their home nation. At 7:32 a.m., only seven minutes after the lead wave of British troops landed, the planks of LCI 527 dropped. The first wave of the 1st Marine Rifle Battalion Commandos (1er Bataillon de Fusiliers Marins Commandos) plunged into water, wearing their standard green berets instead of steel helmets. Powered by adrenaline, they strove toward the beach. Either through skillful aim or pure luck, a German round struck the craft’s landing planks as the second wave of Frenchmen prepared to depart.

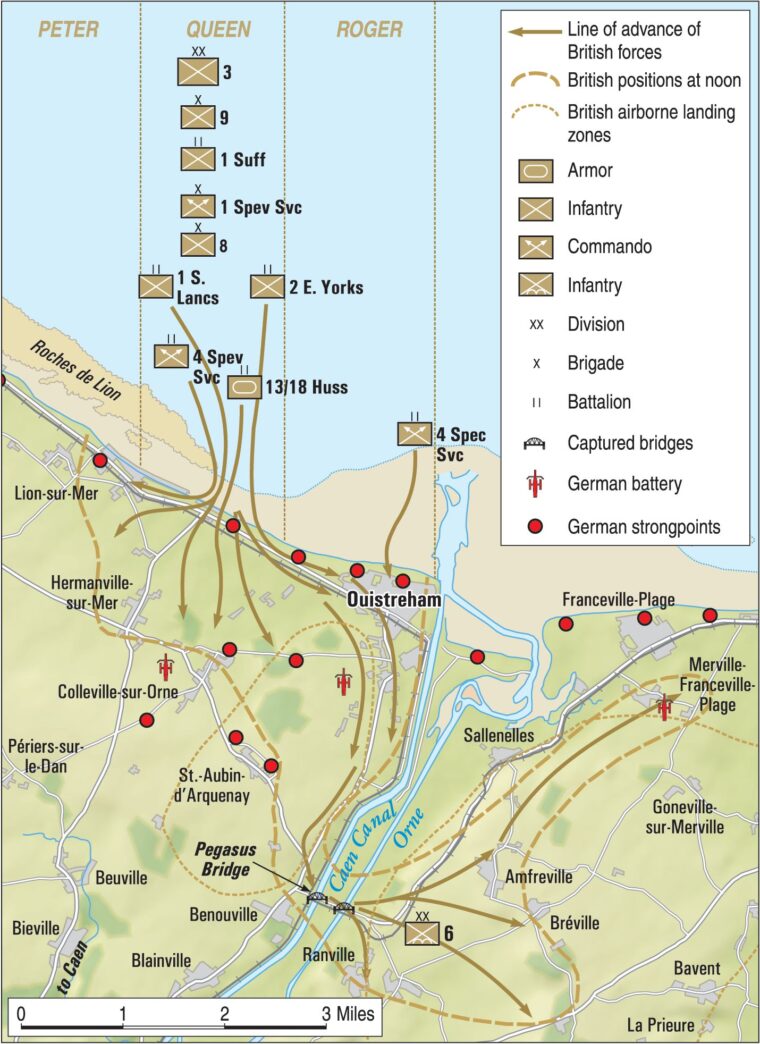

While the remaining soldiers and the LCI’s crew members dropped scaling nets so the commandos could fulfill their part in Operation Overlord, the first French troops made their way onto terra firma. As the French commander advanced, urging on his countrymen, a mortar fragment struck him in the thigh. Despite the injury, he pressed forward. Kieffer still believed in completing the task given by Dawson. No. 4 Commando was ordered to advance into the seaside town of Ouistreham, east of the beachhead. Given the honor of leading the advance, Kieffer’s unit had been assigned to eliminate a German strongpoint that had been built on the ground of a demolished casino. After completing this task and linking back up with the British, No. 4 Commando would march to a pair of key bridges held by British paratroopers. The last part of the plan was to join up with Lovat’s brigade and secure the far eastern flank of the Allied beachhead in Normandy. Since their inception in 1942, Kieffer had been dutifully preparing his men for achievement of these goals.

June 25, 1940, would go down in French history as one of the nation’s worst days with the capitulation to Nazi Germany after early fighting in World War II. One week before, a strong-willed French officer named Charles De Gaulle had issued an appeal from London for French soldiers and civilians to join his cause of continuing the fight against the Germans. Kieffer, then a 40-year-old reserve quartermaster secretary in the navy, joined de Gaulle’s Free French forces the next day. Born in Haiti to French parents and a banker in New York City when World War II began, Kieffer returned to France and enlisted into the French Navy. Along with many countrymen, he escaped to England. Pledging his support to de Gaulle, Kieffer joined the Forces Navales Francaises Libres (FNFL) or “Free French Naval Forces.”

Stationed aboard the old French battleship L’Amiral Courbet, which the British docked in Portsmouth to aid in the port city’s antiaircraft defense, sub-Lieutenant (Sous-Lieutenant) Kieffer was among the staff officers on board. He became aware of the newly formed British Commandos and learned of their operations on Norway’s Lofoten Islands. Encouraged by these daring raids, he put forth a proposal to create a similar force for the FNFL. Admiral Emile Muselier supported the idea, however he informed Kieffer a lack of funding would not permit its implementation. Muselier suggested that he convince the British to arm, equip, and train this proposed French Commando unit. Kieffer’s first attempt failed, although he had stressed the advantages of having a French unit conducting raids and operations on French soil. Later that year, Lord Louis Mountbatten took command of Combined Operations. With the strain put on English Commandos and seeing the success of foreign units serving in the Royal Air Force—such as Polish and Czech airmen during the Battle of Britain— Lord Mountbatten was open to the idea of creating a commando unit composed of troops-in-exile from the occupied countries.

Much to Kieffer’s relief and elation, authorization to create a French commando unit was granted in March, 1941. Part of the FNFL, this unit quickly possessed a core to build around with the recruitment of Lieutenant Charles Trempel, Warrant Officer Francis Vourc’h, and 16 marines, five of them released from detention upon their volunteering. Though wearing standard British battle dress, the Frenchmen retained their traditional blue berets capped with a red pompom. By summer the ranks grew to around 40 men, all with their own tales of how they arrived in Britain to volunteer for 1st Marine Company (1er Compagnie Marin). Jean Gautier, an Austrian who had changed his name from Zivohlava to avoid Gestapo attention while living in Paris, escaped France via ship heading for Canada. In mid-journey that ship sank after being torpedoed. Rescued by another ship in the convoy, safety lasted only a short time as the Germans also sank that ship. With luck or perhaps fate on his side, he was then rescued by a merchantman heading to England. Arriving with only the clothes he was wearing, Gautier was detained and screened. The Austrian eventually was allowed to join Kieffer’s fledgling unit. Another volunteer, Hebert Faure, escaped from a prison camp and arrived in England via Portugal.

Throughout 1941, the French volunteers trained and conditioned to build their stamina and health back to pre-surrender conditioning levels. At Achnacarry, Scotland, a training facility had been established for the British Commandos. In March 1942, Kieffer’s company became the first foreign unit to train there. An extensive and grueling regimen of climbing mountains, fording rivers, and running miles with full backpacks further hardened the French soldiers into a cohesive military unit. The 1er Compagnie Marin not only underwent physical training and marches, but the men attended lectures. Unfortunately, not all who began the regimen survived and an unknown number died. But motivation to one day free their homeland pushed the men to complete the training and earn their green beret (beret vert).

On July 2, 1942, Lord Mountbatten’s vision became a reality with the creation of the No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando. Its structure followed the 1940 Commando structure of a headquarters and four troops with the potential to increase the number to eight troops. By October 1942, No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando grew to six troops, all varying in size. Along with No. 1 (French) Troop, the formation initially included No. 2 (Dutch) Troop and No. 3 (X) Troop. The latter, also known as No. 3 (British) Troop, was mostly made up of Jews of German, Austrian, and Eastern European ethnicity. After the Commando’s official creation, volunteers allowed for the establishment of the No. 4 (Belgian) Troop, No. 5 (Norwegian),Troop and No. 6 (Polish) Troop.

Men from Kieffer’s No. (French) 1 Troop and the No. 3 (British) Troop saw the first official combat action for No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando on August 19, 1942. Sixteen Frenchmen from Sub-Lieutenant Guy Vourc’h’s section accompanied the Canadians and British on Operation Jubilee’s ill-fated landing at Dieppe on the French coast. Although told to remove their “Commando” and “France” shoulder titles and wear steel helmets instead of the naval berets, these instructions were ignored. Attached to British No. 3 and No. 4 Commando as well as divided between various Canadian brigades, these men were given three assignments: act as interpreters, gather intelligence, and recruit any Frenchmen willing to return to England and join Free French forces. Of those French commandos involved, one was executed when the Germans saw his “Commando” and “France” shoulder titles while another went missing for months before finding his way back to England.

Not until mid-1943 did the potential for another operation occur. The French commandos were put on alert for possible operation in Corsica or a raid on the German U-Boat pens located at Lorient. Neither operation took place as the French would soon be employed elsewhere. By the end of 1943, No. 7 (Yugoslavian) Troop and a second French Troop increased the strength of No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando. No. 8 (French) Troop consisted primarily of men from the 2nd Marine Rifle Battalion (2eme Bataillon de Fusiliers Marins). This unit had been stationed in Lebanon before being disbanded. With two troops, on October 8, 1943, the French contingent became 1er Bataillon de Fusiliers Marins Commandos (1er BFMC). Kieffer established a battalion headquarters. Sub-Lieutenant Alex Lofi took over command of No. 1 Troop while Lieutenant Charles Trempel commanded No. 8 Troop. By this time the French had been based at Criccieth in North Wales.

Between Operations Jubilee and Overlord, French commandos participated in small-scale operations along the northern coast of France. Prior to redesignation as 1er BMFC, from July to September 1943, a series of raids under the code name Operation Forfar occurred, with men from No. 1 (French) Troop involved in one of its six operations. Goals were to collect intelligence about German defenses along the coast and the capture of prisoners for interrogation. In total, the Operation Forfar raids were not very successful. No prisoners were taken, and minimal information was brought back.

At the end of December 1943, British Commando units again undertook a series of raids along the French coast as well as on the Channel Islands. Overall code named Operation Hardtack, from No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando, both French troops sent men to participate in some of the missions. As with the raids of Operation Forfar, the goals were reconnaissance of German coastal defenses and, if possible, bringing back prisoners. Weather hampered more than one of the raids by forcing the assault group to return to England. Out of all of the Hardtacks, only Hardtack 21 yielded a positive result. Led by Sous-Lieutenant Vourc’h, the six men from No. 1 (French) Troop arrived at Quineville at 11:50 p.m. on December 26. Moving inland they discovered an antitank beach obstacle known as “Element-C.” The French took detailed notes about this framework of horizontal and vertical steel rails sunk into a concrete base fitted with rollers.

Developed by the French in the early 1930s, the 2.5-ton Element-C would be used against them and the Allies in Normandy. For his successful leadership, Vourc’h earned No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando’s first Military Cross.

Misfortune struck in another recon operation along the Dutch coast on February 27-28, 1944. Lieutenant Trempel and five members of No. 8 Troop went missing during the mission. Graves discovered after the war led investigators to conclude that five men had died of exposure and one had drowned.

Six weeks later, Kieffer and men were transferred to No. 4 Commando, part of the recently formed 1st Special Service Brigade.

By early 1944, Brigadier Simon Fraser, the 15th Lord Lovat took over command of the 1st Special Service Brigade, having previously led No. 4 Commando. He was familiar with the French commandos from their participation in the Dieppe raid. With the planning of Operation Overlord underway, Lord Lovat knew his brigade, which consisted of Nos. 3, 4, 6 and 45 (Royal Marine) Commando, was assigned to Sword Beach, the furthest east of the Allied landing zones. He delegated to No. 4 Commando the task of silencing specific German coastal batteries on and near Sword Beach and then defending the far-left flank of the Allied area of control. Aware that No. 4 lacked sufficient strength as well as the fact that most troops of No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando were not being utilized, Lovat requested and received permission to transfer Nos. 1 and 8 (French) Troop to the 1st Special Service Brigade. He proceeded to offer them to No. 4 Commander Lieutenant Colonel Dawson, who as previously noted spoke French fluently. Also familiar with their capabilities from Operation Jubilee, Dawson gladly accepted the additional men. On April 16, 1944, Nos. 1 and 8 (French) Troops joined No. 4 Commando, becoming its Nos. 5 and 6 Troop, respectively. Renamed Le Franco-Britannique Commando, the French adopted Army ranks in lieu of naval ranks. Though difficult at first, a regimen was hashed out that meshed British and French training styles.

The British 3rd Infantry Division received the task of landing first at Sword Beach. Broken down into sectors, two kilometers west of Riva-Ouistreham, the specific landing sites were given the codenames Queen White and Queen Red. Its 8th Brigade’s 2nd East Yorkshire Regiment, also called the 2nd East Yorks, would be given the crucial mission of being first and securing the Queen Red beachhead. Support for the infantry came from the 13/18th Hussars and its amphibious Sherman Duplex Drive (DD) tanks. Additional armored firepower came courtesy of the Royal Marines 5th Independent Armoured Support Battery.

Employing the Centaur IV, armed with a 95mm howitzer, this unit provided close support for the infantry. Its primary mission would be eliminating hardpoints and other difficult defenses. Soldiers landing on the beach welcomed the Centaur IV’s ability to fire suppressing rounds while they were still motoring toward the beachhead in their landing craft. After arriving on Queen Red beach, Dawson’s Commando was assigned to silence the German strongpoints in Ouistreham, near the mouth of the Caen Canal.

This area was held by the 736th Grenadier Regiment of the German 716th Infantry Division. The regiment’s 2nd Company controlled the area that Dawson would assign to his French troops. As part of their Atlantic Wall defensive system, the Germans had constructed strongpoints —Wiederstandnester (WN). In addition to one that dominated the Sword Beach sector where the British were landing, a pair had been built at Ouistreham. WN-08 oversaw access to locks for the canal. This was No. 4 Commando’s D-Day objective.

To the west, on the site of a demolished casino, the Germans built WN-10, also called the Riva Bella strongpoint. Its main function was to guard access to WN-08. This would be the objective of the 177 Free French commandos.

Aerial photographs of WN-10 and other reconnaissance showed the primary armament was a 75mm Pak 40 anti-tank cannon built into a roofed casemate. A short distance from this sat a 50mm Pak L/40 anti-tank gun in a Ringstand bunker. These were circular, reinforced concrete bunkers, also known as Tobruk bunkers. Three smaller scaled Tobruks, built for machine guns, provided defense against infantry assaults. These emplacements and other weapon pits were connected via a series of trenches. According to Corporal Maurice Chauvet, at least a dozen pillboxes had been constructed along their assault path toward the strongpoint. Further complicating the French mission, anti-tank trenches and automatic flamethrowers protected the area. Overlooking the entire strongpoint, a water tower provided up-to-date information on any approaching enemy. The Germans placed what most sources reported as a 20mm antiaircraft gun atop the water tower.

Dawson felt it would be best to provide the French with their own objective due to potential language complications. To increase the unit’s firepower capability in the operation, No. 4 Commando received a version of the .303-caliber Vickers K-Gun. These defensive armaments for the Catalina flying boat used a drum magazine and fired at a rate of 1,000 rounds per minute. For infantry use, these machine guns were fitted with a bipod. Given the enormity of the French task, Dawson supplied four of these weapons to Kieffer. These probably had been supplied to the two French troops before they and the rest of the 1st Special Service Brigade arrived at Titchfield Camp by May 25. In addition, Dawson lent six men from Royal Signal for communications. Once both groups accomplished their respective tasks in Ouistreham, they were to regroup and then proceed to a pair of crucial bridges, one over the Caen Canal (Pegasus Bridge) and the other over the Orne River, that were to be captured and held by paratroopers of the British 6th Airbourne Division in a daring pre-dawn airborne mission.

In overall command of the two French Troops, Kieffer led from his small Headquarters section. Lieutenant Vourc’h commanded No. 5 Troop. In his troop served Sergeant Guy, Comte de Montlaur. Unconfirmed lore has arisen that Sergeant de Montlaur stated he looked forward to taking the Riva Bella strongpoint as he had lost a fair amount of money at the former casino. To lead Troop 6, Kieffer assigned Lieutenant Lofi, while selecting Lt. Pierre Marc Azoulay-Amaury as commander of the 32-man K-Gun Troop. Capt. Robert Lion served as the battalion’s medical officer, most likely assisted by a pair of British orderlies. Like Dr. Lion, the unit’s chaplain, Father Rene du Naurois, had escaped from Vichy France to join de Gaulle’s cause.

Kieffer and his men had known about their assignment since the beginning of May. Lofi’s troop was given the task of clearing the dunes on the beach, which included a passageway through mines and barbed wire obstructions. Although the 2nd East Yorks and supporting elements ideally would have the beachhead under sufficient control by the time the French were scheduled to land, the experienced Kieffer knew that the best laid plans are scrapped upon first contact. There stood a good chance that his men would have to assist in taking the beachhead. On the journey across the English Channel, the French commander insisted upon the English operators of the LCIs landing as far to the east on Queen Red as possible. Using aerial photographs, he and his officers outlined a detailed plan of attack upon reaching the western edge of Ouistreham. After landing, the entire No. 4 Commando would assemble at a deserted children’s holiday camp 250 yards inland. Some men recognized their target area; one commando mentioned he once worked near the canal locks. Upon learning that some French soldiers had intimate knowledge of the objective location, the British confined the contingent to the camp until they were to board the craft for the operation. On the eve of the invasion, Lovat addressed Kieffer’s men in French. He told them that tomorrow they would be the first French soldiers to fight the enemy in their homeland.

On June 5, the French took transportation to Warsash (near Southampton), the site for the loading of the LCIs. Around 3 p.m., Lofi’s No. 6 (No. 8 French) Troop plus two Vickers K-Guns boarded LCI 523. Kieffer and No. 5 (No. 1 French) Troop took their place aboard LCI 527 with the remaining pair of K-Guns. “No return ticket, please,” replied Corporal Gautier to the British officer in charge of loading LCI 523 upon the calling of his name. At 10:30 p.m., the two LCIs departed England as part of the most famous invasion force in history. Rough and stormy seas impacted the journey across the Channel. A number of the French commandos suffered seasickness on the voyage. Both Lovat and Dawson agreed to give the 1er Bataillon de Fusiliers Marins Commandos the honor of leading No. 4 Commando onto the soil of their homeland.

After walking around the LCI and talking to many of his men, Kieffer retired for the night. Before going to bed, he remembered the prayer of Sir James Astley at the 1642 English Civil War Battle of Newbury. “Lord, I shall be very busy this day. I may forget thee, but do not thou forget me.” Through the early hours of June 6, the Allied invasion fleet sailed toward its destination, the coast of Normandy. Those on deck saw or heard the air armada carrying elite paratroopers. At 5 a.m., a sailor on each of the LCIs informed the French that it was time.

Kieffer ate a small breakfast before joining Vourc’h’s men. While the men began preparing, at 5:10 a.m., the naval bombardment commenced, starting with the light cruiser HMS Orion blasting German positions on Gold Beach. Not long after that, the armada allocated to support the invasion of Sword Beach joined the onslaught. Targeting the two Wiederstandnester in Ouistreham, the heavy cruiser HMS Frobisher fired numerous shells from its 7.5” main guns. Aboard the two LCIs, the French Commandos, as with all units in the 1st Special Service Brigade, proudly wore their hard-earned beret vert. Continuing toward Queen Red, the French observed Allied bombers overhead and may have heard that Rome had been entered by the Americans. Desiring to record the details of this momentous day, Kieffer witnessed the naval bombardment of German defenses, but with increasing difficulty as smoke from Allied shells obscured his view. Many noted long trails of smoke from volleys of rockets streaking toward this area of Sword Beach, also called the “La Breche.” He recalled seeing examples of the beach obstacles implemented by German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. At 7:25 a.m., he watched as 13/18th Hussar Sherman DD tanks and the men of the 2nd East Yorks began landing under fire.

The British crews of LCI 523 and LCI 527 performed their task to perfection as they approached the far left of Queen Red Sector. Commandos armed with Bren light machine guns readied themselves to lay down support for their fellow soldiers. Others, armed with British-made PIATs (Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank) and Bangalore torpedoes to deal with barbed wire and other hardpoints, awaited the moment when their specific weapon would be needed. Despite knowing that not all would survive this day, or even the next few minutes, the men did not let fear control their actions. After all, these elite soldiers were about to take the first steps to liberate their country. Among the first to disembark when the ramps were deployed stood Troop 5 commander Vourc’h.

At 7:32 a.m., LCI 523 dropped its bow ramps, 30 yards from solid ground as remembered by Corporal Chauvet. The order to disembark was given, and out poured the first men from Lofi’s troop. Almost simultaneously and 50 yards laterally, the planks of LCI 527 splashed into the water. Lt. Vourc’h and the first group of No. 5 Troop rushed toward the beach bearing 80-lb. packs filled with four days of ammunition and rations on their backs. With machine-gun fire and mortar rounds landing all around the Allied invaders, the third Frenchman to arrive on the beach went down, seriously wounded. In his written account of his war experiences, Beret Vert, Captain Kieffer recalled that just before the second wave was to depart LCI 527 into the waist-deep waters, “…a 75mm shell swept away the gangplanks of the barge in a tearing of wood and metal.”

To continue the mission, scaling nets were dropped over the sides of the stricken LCI. After unloading No. 6 Troop and their accompanying K-Guns, the British crew of LCI 523 maneuvered their craft along LCI 527 for the French to climb aboard and stream down its ramps. Differences have arisen over the predicament of the 2nd East Yorks. Some French soldiers recall that the British had not progressed far past the waterline, a claim hotly disputed by the 2nd East Yorkshire Regiment. The formidable German strongpoint WN-20, overlooking the Queen sector beaches, could account for the progress of the British assault. Perhaps a round from its 75mm anti-tank gun destroyed LCI 527’s landing planks. Gautier remarked seeing more than a few knocked-out British tanks as he rushed up the beach.

At some point, Kieffer received the shrapnel wound in his left thigh. Though it would become a serious complication in a couple of days, the Haitian-born officer continued his mission. Shortly after the French landed, No. 4 Commando stormed ashore. Dawson took a wound to the leg almost immediately and then was hit again in the head. Both wounds were not serious enough, as he stayed with men. With Lieutenant Vourc’h wounded, Lieutenant Mazeas took over command of No.5 Troop. Few Ouistreham residents remained in their village after the Germans had evicted them in May. Yet, one who stayed behind met the Allied troops. Somewhat suspicious at first, his attitude warmed when the French troops told him that they were here to stay.

Over the next 15 minutes, the two French Troops made their way inland, steering to the abandoned holiday camp. A sergeant cut through a barbed wire obstacle barring the path. Passing through the subsequent mines, the commandos rallied at the holiday camp. Once all arrived, the men took a few minutes to inspect their weapons and reload ammunition, as well as preparing themselves mentally for what they were about to undertake. Their heavy backpacks were left behind not far from the holiday camp to be picked up after the silencing of the Riva Bella strongpoint. From the 177 Frenchmen and eight British subordinated to the unit, 16 commandos failed to arrive at the Lion-sur-Mer holiday camp, plus at least one of the British communication operators. Four of the battalion’s 13 officers had been wounded.

This included Mazeas, who was wounded performing a short recon from the holiday camp in preparation for the march to Ouistreham. Due to the high percentage of officer casualties, Kieffer disbanded the battalion’s headquarters and personally took command of No. 5 Troop with Sgt.-Maj. Herbert Faure as his second-in-command. Being a professional soldier, Kieffer knew this operation had to remain on schedule. He prepared his men to move out, leaving the second assault wave to care for his wounded and dead.

With all of No. 4 Commando at the forming-up location, the drive toward Ouistreham commenced at 8:15 a.m. Again, Dawson permitted the French the honor of leading it, Lofi’s Troop 6 on point. Once into the ruins of the seaside village, the force made its way toward Boulevard Marechal Joffre, which would take them straight at their objective. Upon reaching the crossroad of Avenue de Pasteur, Dawson’s commandos turned onto it and proceeded toward its target, WN-08, near the mouth of the Caen Canal. Following Lofi’s troop, Amaury’s K-Gun section brought their four machines. The No. 5 Troop brought up the rear with Kieffer letting Faure direct it. The lead men of Lofi’s troop turned onto the boulevard five minutes after leaving the holiday camp.

To capture and silence WN-10, the two troops, each supported by a pair of K-Guns, would maneuver to attack the German stronghold from the rear via different directions. Each of these attack formations were further broken down into smaller groups with the necessary equipment and weapons. The size of each group depended on the specific target assigned to them. Weapon-wise, each subgroup had at least two Bren guns, a soldier armed with a Thompson submachine gun, and one flamethrower. The Bangalore torpedoes were discovered to be useless, thoroughly soaked when the men stormed the beach.

By advancing this way, Kieffer felt each subgroup would be able to mutually support the other. As the squads closed in on the Riva Bella strongpoint, German resistance stiffened. Lieutenant Lofi received a minor wound but persevered. Using the remains of the buildings and mouse-holing through fences to minimize exposure to fire, the French commandos gradually made their way toward WN-10.

As aerial photographs provided a limited aspect of the subject, the advancing soldiers saw that most of the strongpoint’s emplacements sat below ground level or in fieldworks. Casualties among those scouting ahead increased. In addition to dealing with machine guns and mortar rounds striking their positions, the attackers came under fire from snipers.

The Frenchmen knew the accuracy of the German fire resulted from the tower-based observation post that radioed the French movements to the defenders. The experiences varied between the subgroups. While some got held up from previously undetected trenches, others overran sites that on the aerial photographs showed machine-gun nests but were found empty.

Though manpower decreased as the commandos battled toward their objective, firepower stayed the same with the troops exchanging their rifles for the more powerful Bren guns and Thompsons. A couple of soldiers armed with PIATs positioned themselves in a villa across a square from the casemated 75mm gun, but they only had four rounds. They used two of them to take out an antiaircraft gun employed in a ground defense role. They fired the remaining two rounds at the structure with the 75mm anti-tank cannon, inflicting little damage, and got out of the villa before it was blasted to ruins.

A pair of the K-Guns set up in a bomb crater on the right flank provided covering fire for an assault attempt. Once alerted to this fact, a small group of Germans began to outflank them. Kieffer learned that an officer overseeing the situation took a sniper round to the head while trying to alert the K-Gun crews of the impending danger. The situation worsened when both K-Guns jammed one after the other. The gun crews took refuge in a nearby building where both weapons had to be stripped down and thoroughly cleaned.

In the midst of the ongoing battle, a World War I veteran appeared among the French soldiers. A member of the French Resistance, Marcel Lefevre had a precise knowledge of German locations and he advised the commandos on the safest routes to approach the various enemy strongpoints. Lefevre also said he knew where the communication cables from the tower to WN-10 were buried. Informed of the location, Faure and another man armed with a pair of 8-lb. charges of plastic explosives went to deal with them. The demolition charges severed both the communication lines and the power cables for the automatic flamethrowers.

The French bravely approached the blockhouses, firing Bren guns, K-Guns, and PIATs that had no effect. German fire poured forth, destroying structures used by the French and inflicting casualties. The battle had been going on for only 30 minutes when Dr. Lion was killed instantly by a sniper shot through the heart as he attended a wounded soldier. As the chances of success diminished with every casualty, Kieffer concluded that his men must make one last attempt, a frontal assault, before the 1er BMFC became insufficient to eliminate their objective. As he hesitated to issue the order, Kieffer heard over the radio that six Centaur IVs from the Royal Marines 5th Independent Armoured Support Battery had landed on the beach.

Quite aware of the extremely low probability of overcoming the German strongpoint without heavy support, Kieffer decided to get the necessary assistance. He ordered his troops to dig in and not take unnecessary risks until he returned. The French commander headed back to the beach with his batman, Private Ferdinand Devager. At the beach Kieffer convinced the British that his men desperately needed support. He and Devager climbed onto the engine deck of a vehicle commanded by Sgt. E.R. Woods and directed it to the battle.

“It was 9:25 a.m. when the Centaur arrived in front of the obstacle,” wrote Kieffer. He directed the Centaur, not a 13/18th Hussars Sherman DD tank as popularly believed, into a position where it was partially covered from enemy shells and had the close support vehicle fire on the casemated 75mm. “The first two shells hit the casino dome squarely and the enemy guns fell silent immediately,” wrote Kieffer in his report. In addition to being buffeted by the blast wave from the 95mm rounds of the Centaur IV, a rifle round struck the French commander in his right forearm. Jumping off the vehicle with his batman, he repositioned the Centaur. The twice-wounded Kieffer directed Woods via hand signals to the placement of a dozen more rounds into the German defenses.

Keeping the enemy off balance, the French rushed the strongpoint, storming through trenches, machine-guns nests, and Tobruks. Directed to split into two attack sections, Faure had Sergeant de Montlaur lead the group attacking on the left and a sergeant-major attack to the right. De Montlaur’s group made good progress, but those on the right stalled in the face of fire from the antiaircraft gun atop the tower. In response, Woods had his gunner fire at the tower. After four rounds, the top portion of the tower disintegrated. Kieffer, in his report to French Rear Admiral Georges d’Argenlieu, specifically remarked on the support and conduct of the Centaur commander during the battle.

The French started mop-up operations at 9:55 a.m. With their escape route blocked, the German soldiers began to leave their bunkers and surrender. While one batch of 11 prisoners was being marched away, one of them used a grenade that injured two men. Retaliation was immediate as nearby commandos fired upon the Germans, killing three. News came in over the radio about successful captures of strongpoints throughout Sword Beach, the drive inland, and the flow of German prisoners to the holding areas established on the beach. By 11:20 a.m., fighting was winding down when Kieffer received the order from Dawson for No. 4 Commando to assemble near the holiday camp.

At 12:40 p.m., Kieffer’s two troops arrived back at the location of their stashed backpacks. Replenishing ammunition and strapping on their packs, the French were ready to move out with No. 4 Commando, which had successfully completed its objective roughly the same time as its French comrades. Twenty-five minutes later, Dawson’s unit hastily made its way to the British paratroopers and the bridges they held. This time Kieffer’s men provided rearguard duty. Dealing with hidden mines along the path and the occasional sniper, the trek passed with little difficulty. The last members of Lovat’s 1st Special Service Brigade to reach the bridges, No. 4 Commando, arrived in Benouville. Fighting still raged in the area, though the paratroopers controlled the bridges over the Caen Canal and the Orne River. But the constant sniper fire, along with mortar and artillery barrages, made crossing them hazardous. For cover, the British employed a smoke screen covering the bridge and opposite bank. The French loaded their K-Guns onto jeeps for the crossing. With a mad dash at 4:15 p.m., British and French soldiers crossed the two waterways. The smoke was thinning when the last group went across the Orne River and three French commandos were wounded.

No. 4 Commando marched eastward to set up a defensive perimeter. Dawson ordered the 1er BFMC to hold the area between Amfreville and Le Plein. As night fell at 8 p.m., the French soldiers built up a defensive perimeter through digging trenches, setting up camouflaged machine-gun pits, and positioning PIATs. Despite a long and exhausting day, the inevitable German counterattack necessitated this essential labor. The French and fellow British commandos could then look back on the day in which all objectives assigned had been successfully completed. For his action on June 6, the British awarded Lieutenant Commander Kieffer the Military Cross. The first day of the retaking of Western Europe from Nazi Germany was not without cost. From their landing on Sword Beach to securing a bridgehead east of the Orne River, the battalion suffered 10 killed in action and 31 wounded on the first day of the Normandy Campaign.

With his thigh wound seriously inflamed, Kieffer was ordered into medical treatment on June 8. Under Lofi’s command, the French fought hard to hold their sector. A week later Kieffer returned from treatment and led the men in the drive for the Seine River, during which they assisted in the liberation of a number of towns. Withdrawn to England on September 5, only 40 of the original 177 soldiers remained unscathed.

In November, the French participated in Operation Infatuate I alongside No. 2 (Dutch) Troop from No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando. The French and Dutch part of this operation took the form of a seaborne landing on the western end of the Netherlands’ Walcheren Island with the objective of capturing the port of Flushing, while at the same time to the east, a Canadian brigade forced a crossing from the mainland. The last action of now three French troops took place in March 1945, conducting raids against the island of Schouwen. After the war, The French Armed Forces absorbed the three French troops as their own commandos.

John E. Spindler is a regular contributor to Military Heritage. This is his first article for WWII History.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments