By Peter Kross

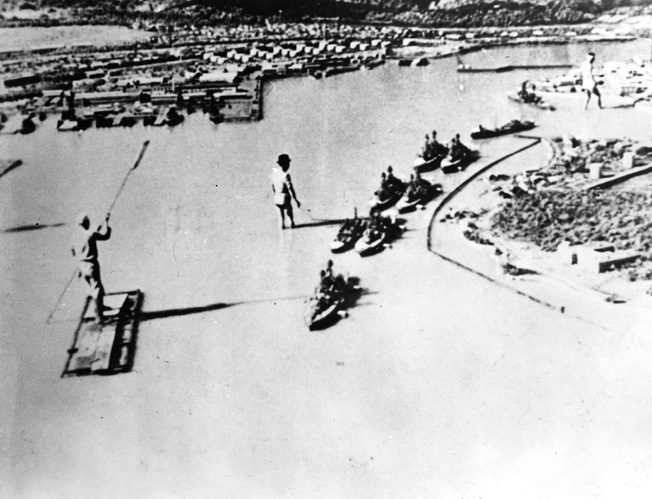

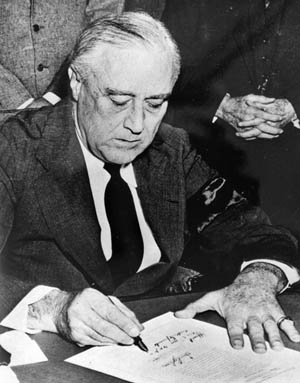

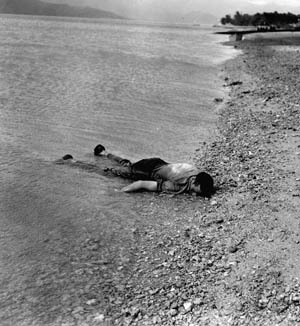

The Japanese strike on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941—a “Day of Infamy,” as President Franklin D. Roosevelt described it—left the American Pacific Fleet in almost total ruin, plunged the United States into World War II, and set off a controversy regarding the events that led up to the attack that is still being hotly debated.

[text_ad]

One of the most troublesome incidents in the pre-Pearl Harbor planning by the Japanese is the so-called “Winds Code” incident and what significance, if any, it had for the American code breakers who were monitoring Japanese diplomatic and military communications in the months leading up to the surprise attack.

Did the Navy cover up by not allowing the people who handled the Winds communication to testify before congressional committees after the war? And what happened to the Winds communications itself that was supposed to have been seen by different naval intelligence personnel in the days prior to the Pearl Harbor attack?

To understand the significance of the Winds message, we must trace the role of the U.S. military’s efforts in breaking the Japanese codes before Pearl Harbor.

Decrypting Magic

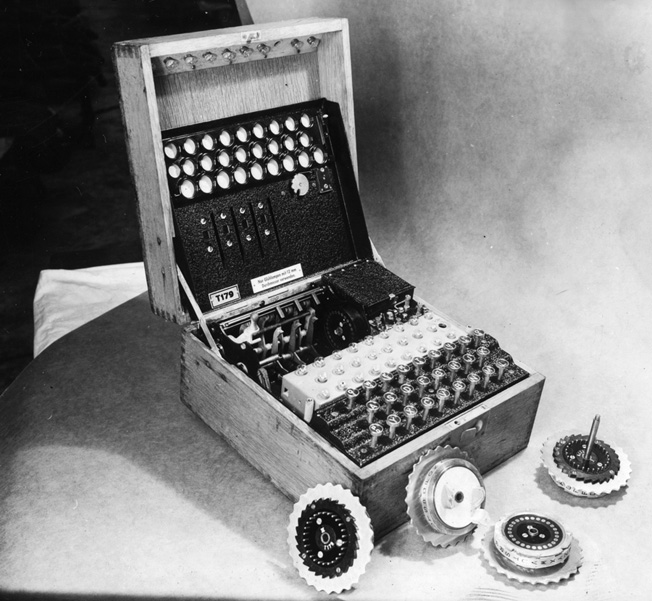

The Japanese used what they called a “Purple” machine to encode top-secret intelligence sent to their embassies around the world. The code word for American intercepts of Japanese diplomatic and military messages coming into the United States was “Magic.” The United States designated all the information collected from Purple as “Magic”—the highest-classified intelligence collected by the United States during the war.

The success of Magic allowed the United States to follow Japan’s route to war, keeping a detailed record of their every move. During the summer of 1940, the United States began sharing intelligence with the British who had their own secret communications vis a vis Germany called “Enigma.” In a move that would later prove disastrous in the pre-Pearl Harbor scenario, one of the Purple machines that went to the British was originally supposed to be given to the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor.

Another U.S. military organization doing cryptographic work that involved both Magic and the Winds communication was the Navy’s code-breaking group called OP-20G, led by Commander Laurance Safford.

The Magic information collected by the Navy was sent to various top military and civilian leaders in the American government. Unfortunately, Magic was not shared with all of the top military commanders including, most importantly, Navy Admiral Husband Kimmel and Army General Walter Short, the two commanding officers at Pearl Harbor.

Another unfortunate side of Magic was that the men who were apprised of its content could not agree among themselves as to which information was relevant or not. It was this lack of communication that led to the controversy over what the Winds message really meant.

Uncovering Japan’s Intentions

By the fall of 1941, U.S. code breakers had a pretty good idea as to what the Japanese government was thinking and planning regarding a potential conflict with the United States. Japan was still committed to its participation in the Tripartite Pact with Italy and Germany and refused to remove its troops from China. From the intercepts of Japanese communications that were picked up by U.S. code breakers, it was obvious that Japan was disinclined to tone down its harsh rhetoric regarding a possible war with either the United States or Great Britain.

More importantly, as far as the United States was concerned, a November 5, 1941, message from Tokyo to Washington setting a date of November 25, 1941, as a deadline for the completion of diplomatic negotiations with the United States, should have been a warning sign that trouble lay ahead.

Other intercepted communications from Tokyo gave instructions for the destruction of its code machines; a November 20 message from Tokyo stated that the current conditions would not “permit any further conciliation by us [Japan];” a November 22 note said if a diplomatic agreement was not reached by November 29 “that things are automatically going to happen.” Also important to the prewar scenario was a November 27 war warning message broadcast from Tokyo, along with a November 19 message from Tokyo giving details of the “Winds Execute” message that would be added to the end of the Japanese news broadcasts in case war between the United States, England, and Russia was imminent, and a November 19 note giving further instructions for Japanese diplomats in Washington to listen for Winds messages that would be read five times at the beginning and end of each transmission.

Uncovering the Winds Code Words

On December 4, 1941, American listening posts in various parts of the world decoded two communications sent from Tokyo to its Washington embassy on November 19 that carried information on the so-called Winds message to which naval intelligence officials had been alerted.

The first message, Circular No. 2353, said: “Regarding the broadcast of a special message in an emergency. In case of emergency (danger of cutting off our diplomatic relations), and the cutting off of international communications, the following will be added in the middle of the daily Japanese language short wave news broadcast:

In case of a Japan-US relations in danger HIGASHI NO KAZEAME––East Wind Rain.

Japan-USSR relations: KITANOKAZE KUMORI––North Wind Cloudy.

Japan-British relations: NISHI NO KAZE HARE––West Wind Clear.”

The second circular, No. 2354, came later:

“If it is Japan-US relations: HIGASHI.

Japan-Russia relations: KITA.

Japanese-British relations (including Thai, Malaya, and Netherlands East Indies): NISHI.

The above will be repeated five times and included at beginning and end. Relay to Rio de Janeiro, Mexico City, San Francisco.”

The Winds message was also picked up by a variety of Allied listening posts across the globe. The British Singapore station seized the message on November 28 and transmitted it to the U.S. Asiatic Fleet headquarters where Admiral Thomas Hart, the commander in chief, Asiatic Fleet, sent it to the headquarters commanders of both the 14th Naval District and the 16th Naval District. On December 4, the message was sent by Consul General Walter Foote at Batavia to the State Department in Washington. In his message regarding the broadcast, Consul General Foote said, “I attach little or no importance and view it with some suspicion. Such have been common since 1936.”

The same low-key reaction to the Winds message came on December 3, when a top U.S. Army officer stationed in Java cabled the message to Brig. Gen. Sherman Miles, the acting ACS/Intelligence head, War Department. It was broadcast in a low-grade designation called “deferred,” and was subsequently not decoded until 1:45 am on December 5.

These two messages were sent from Tokyo on their J-19 diplomatic code, not the more significant Purple code that U.S. naval intelligence had been privy to for months. On the Navy’s part, they alerted all their stations to be on the lookout for the next phase of the Winds code––the so called “Execute” stage of the plan.

Station “M” Finds the Smoking Gun

Subsequently, a full-court press inside the United States was ordered to listen for the “Execute” phase. Naval code-breaking stations in San Francisco and Fort Hunt in Virginia had Japanese-language translators sent in on an emergency basis. The Federal Communications Commission, one of whose jobs was the monitoring of Japanese weather broadcasts, was put on alert. If they picked up an “Execute” broadcast, they were to call Colonel Rufus Bratton, commander of the G-2 (Army Intelligence) Far

Eastern Section.

In Hawaii, the Navy’s top intelligence code breaker, Joseph Rochefort—head of the Combat Intelligence Unit of the 14th Naval District in Pearl Harbor and Station Hypo, a U.S. monitoring unit that watched Japanese naval movements—was alerted to the Winds message.

During this tense time, the FCC picked up a false message from Japan at 10 pm on December 4 which said, “Tokyo today north wind slightly stronger may become cloudy tonight. Tomorrow slightly cloudy and fine weather. Kanagawa Prefecture today north wind cloudy from afternoon more clouds. Chiba Prefecture today north wind clear, may become slightly cloudy. Ocean surface calm.”

One of the U.S. listening posts that played a huge role in the Winds Affair was Station “M,” located at Cheltenham, Maryland. Early on December 4, 1941, 27-year-old senior radio operator Ralph Briggs picked up a cryptic message in a weather forecast being broadcast from Japan. Warned to listen for any unusual weather broadcasts attached to messages from Japan, Briggs heard the words he’d been alerted to. It was “East Wind Rain––HIGASHI NO KAZEAME [a possible disruption of Japan-U.S. relations].” It now seemed that the “smoking gun” from Tokyo had just been received.

Briggs began the process of transmitting his find to the other intelligence agencies and government officials. He sent one copy to the Army Signals Intelligence Unit and another to the White House. The Navy’s OP-20G got their own copy by 9 am on December 4.

The Winds message was then translated by Lt. Cmdr. Alvin Kramer, who was in command of the Translation Section of the Navy Department Communications Unit. According to extemporaneous accounts, Kramer, upon seeing the Winds message, said, “This is it.” By noon on December 4, multiple copies of the Winds message had been circulated among the Army and Navy’s intelligence divisions, their senior officers, the State Department, and the White House. As some conspiracy theorists believe regarding the significance of the Winds message, the Roosevelt administration had three days to read and digest its contents and prepare the country for war with Japan. Yet, nothing was done to alert the fleet at Pearl Harbor or any other branch of the military.

Debate Over the Winds Message

It is at this point in the debate where differences of opinion regarding the significance of the Winds message among its many participants come into play. In his extensive testimony before the Joint Congressional Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor attack, Navy Captain Laurance Safford, who was head of the Navy’s OP-20G Code and Signal Section, told the attentive congressmen that in his opinion, the Winds message was a genuine “signal of execute” that war between the United States and Japan was imminent.

Safford pointed out that on December 4, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy changed its “Operations Code,” which was picked up by Allied listening stations on Corregidor Island in Manila Bay and reported up the chain of command nine hours after it was decoded. Safford said that this change in Japan’s code, as well as the “Execute” message, was the final step in Japan’s preparations for war with the United States.

Safford testified that it was his belief that the Navy had a three-day advance warning about an impending Japanese attack and did nothing to stop it. It is worth noting that despite Captain Safford’s validation of the Winds message, there was no definite proof to back up his assertion that the intercepted message, “East Wind Rain,” was anything more than part of the regular communications traffic that was intercepted on December 4, 1941.

Army chief of staff George Marshall discredited Captain Stafford’s testimony regarding the Winds message, saying that he did not see the message in question. Also, Joseph Rochefort was adamant that he had seen no “Execute” message, despite assertions by others that he had. Another person who had a differing view of the Winds traffic was George Linn, a naval officer attached to OP-20G in 1941. In material provided by Linn, and released by the National Security Agency in November 1980, Linn, who was a good friend of Captain Safford, said that, “Safford’s obsession with the idea that an ‘Execute’ had been received and suppressed had caused him [Safford], to go ‘out on a limb, for there had been no “Execute.” Linn summed up his testimony by saying, “I found nothing, and therefore concluded that an execute had not been received prior to 2400 hours on December 6.”

The Disappearing Winds Message

Adding to the seemingly never-ending debate over the veracity of the Winds message is the fact that the original message had somehow disappeared from all official Navy files just when the Roberts Commission was conducting hearings into the whole Pearl Harbor matter shortly after the attack. What happened to the official Winds message paperwork is still a mystery and its loss has only deepened the skepticism of those who believe that an official cover-up by the Navy or other government agencies took place.

After the war ended, various congressional committees were established to debate the Pearl Harbor attack and try to attach blame where possible. The testimony took on a national scope and many of the top newspapers of the day covered it, sending their best reporters to the hearings. The Winds Execute phase of the hearings took on a circus-like atmosphere with debate and counterdebate swirling like a prairie fire. In 1946, the New York Times said that the Winds message was a “bitter microcosm” of the investigation into American preparations leading up to the attack on December 7, 1941. The Times further noted that, “If there was such a message, the Washington military establishment would have been gravely at fault in not having passed it along to military commanders in Hawaii. If there was not, then the supporters of those commanders would have lost an important prop to their case.”

In later testimony before the Army board regarding the missing Winds message, a number of people who were intimately involved in the affair gave their insights into what might have happened. Captain Safford said that the last time he saw the Winds message it was in the hands of OP-20G. He tasked a Captain Stone to see if he could locate the message but to no avail. When questioned by Maj. Gen. Henry Russell, Stafford said that the Winds message was filed in the Navy’s 7001 file. The following exchange took place between Safford and General Russell:

General Russell: “Well, is JD 7000 in that file now?”

Captain Safford: “JD 7000 is there, and 7002.”

Russell: “But 7001 just isn’t there?”

Safford: “The whole file for the month of December 1941 is present or accounted for except 7001.”

Safford further said that when a thorough check of the 7000 series was made, “That is the only one that is missing or unaccounted for.”

Years later, Ralph Briggs, the radioman at Station M who picked up the Winds message, broke his silence. In 1960, when Briggs was in charge of a unit that contained naval archives from World War II, he stated that, “All transmissions intercepted by me between 0500 thru 1300 on the above date [December 5, 1960] are missing from these files and these intercepts contained the Winds message warning code.”

However, Briggs contradicted himself as to the date he intercepted the Winds execute message. He said that he intercepted it on the evening of December 4, while Safford said it came in at night on December 3. Nevertheless, to make matters more complicated, Briggs’s log relating to the Winds Execute message is dated December 2.

Lieutenant Commander Alvin Kramer gave yet another version of events relating to the Winds affair. He said that the “Execute” message was dated December 5, and that the message only had three lines of text. He testified that, in his estimation, the Winds message concerned a possible war between England and Japan. He further said that he thought the message was “a false alarm of this Winds system. It was, nevertheless, definitely my conception at the time that it was an authentic broadcast of that nature.”

Reviving the Controversy

As the events of the Pearl Harbor attack faded into memory, it seemed that the controversy would finally end; however, that was not the case. The event had so many divergent players, each offering up their own different scenarios, that it would not melt away.

In 2009, two historians, Robert J. Hanyok and the late David P. Mowry of the National Security’s Center for Cryptologic History, wrote a 327-page book called West Wind Clear: Cryptology and the Winds Message Controversy. This little-known book seemed to debunk the view that a clear warning was being monitored before the Pearl Harbor attack.

The institution that wrote the report, the super-secret National Security Agency (NSA) is an interesting place from which to issue such a narrative. Until a few years ago, the NSA’s very existence was shrouded in secrecy. It was dubbed in the media as “No Such Agency” or “Never Say Anything,” even though a public sign on the highway alerted visitors and employees that it, indeed, was there for all to see.

The NSA: Evolution of the Signals Intelligence Service

The NSA evolved out of the World War II Signals Intelligence Service and the Armed Forces Security Agency. The NSA was formally charted in October 1952 via a memorandum that was issued by President Harry Truman.

The main job of the NSA is to collect and analyze all signal intelligence (SIGINT), such as radio intercepts, telephone calls, electronic communications, and faxes coming in from around the world. The other job the agency performs is the cracking of other nation’s secret codes that may contain information that might harm the security of the United States. The headquarters of the NSA is located at Fort George Mead, Maryland, halfway between Washington and Baltimore. From its headquarters, the analysts of the NSA use a number of high-tech platforms such as ships at sea and satellites hovering in space to monitor communications on a global basis.

The NSA has a checkered past, with its veil of secrecy paramount in all its work. The work of the NSA came crashing down in September 1960 when two of its cryptographers, William Martin and Bernon Mitchell, defected to Russia and held a press conference detailing their NSA affiliation. In later years, the agency was caught up in the Bush administration’s war on terror. Some of its tactics—like the reading of American citizens e-mails and the tapping of phone calls, which the agency said it was searching for any links to foreign terrorists—brought a new call for the overhaul of the NSA.

No Actionable Intelligence From Winds

The paper written by Hanyok and Mowry was given little publicity outside of the intelligence community and it has only recently been declassified. In their writing, both Hanyok and Mowry lay to rest any cry of conspiracy in the Winds message as it related to the Pearl Harbor attack. One of the authors told an interviewer, “Some conspiracy buffs might change their minds if they read my book.”

Using previously classified documents relating to the Pearl Harbor attack, the two scholars note, “A Winds Execute message was sent on 7 December, 1941 [and] the weight of the evidence indicates that one coded phrase, ‘West Wind Clear,’ was broadcast according to previous instructions some six to seven hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor.” They write that it is possible that a British listening post might have picked up the broadcast one to two hours after the attack, “but this only substantiates the anticlimactic nature of the broadcast.”

Hanyok and Mowry note, “From a military standpoint, the Winds coded message contained no actionable intelligence either about the Japanese operations in Southeast Asia and absolutely nothing about Pearl Harbor. In reality, the Japanese broadcast the coded phrases long after hostilities began––useless, in fact, to all who might have heard it.”

The authors cite the failures of the memories of so many people who were in the loop at the time for the possible misinterpretations of what they believed happened during that hectic time prior to December 7, 1941.

Hanyok and Mowry are adamant when they assert, “There simply was not one shred of actionable intelligence in any of the messages or transmissions that pointed to the attack on Pearl Harbor.”

Was Captain Laurance Safford to Blame?

They pin most of the blame on Captain Laurance Safford for the 50-plus-year misunderstanding of the Winds message. “Put to the test, though, Safford’s narrative about the Execute message simply failed to stand up to cross-examination. The Joint Congressional Committee shredded Safford’s story. The committee reduced it to the collection of unsubstantiated charges that all along had been its foundation. The documentary evidence [Safford] said was available simply did not, nor did it ever, exist. In truth, Safford produced nothing upon which any further investigation could proceed.”

The two historians also take a shot at the various conspiracy writers and bloggers who believe in Safford and his faith that the Winds Execute message was a genuine war warning. Talking about the various conspiracy writers, they say that “the writers inverted the normal rules of evidentiary argument,” stating that Safford’s testimony has not been officially rebuffed by the government all these many years later.

“The scholars and researchers who championed Safford’s version of the controversy abandoned the rigorous evidentiary requirements of the historical profession in order to advance their own thesis,” they say. “Safford’s case was built on mistaken deductions, reconstructed, nonexistent documents, a mutable version of events, as well as a cast of witnesses that Safford conjured up in his imagination.”

Why the authors have put most of the blame on the shoulders of Laurance Safford, a distinguished Naval officer, a 1916 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, the officer who established the Navy’s communications intelligence unit, is not known, but they must have their reasons.

In an interview with the New York Times, both Hanyok and Mowry say that when the naval officers who had a stake in the use of radio intelligence could not find a copy of the Winds message, they immediately charged a cover up by some people in the naval hierarchy. They also pointed out that when it was learned that the Japanese government began ordering their diplomats to begin destroying their code machines in early December 1941, they did so because it “was possible that they viewed the Japanese actions as ominous, but also contradictory and perhaps even confusing. More importantly, though, the binge of code destructions was occurring without the transmittal of the Winds execute message.”

A Controversy Without Answers

After reading both sides of the historical argument, it is nearly impossible, 65-plus years after the events that took place, to say who was right or wrong. It seems that the Winds Execute message will be debated as long as people have an interest in what took place before America was drawn into World War II. Neither the historical community nor the conspiracy buffs will be happy with the outcome, even with all the new information that has come into the public domain since the original investigations began in 1946.

What the historical record can attest to is that the Winds Execute message was so fraught with differing opinions, false leads, calls of a cover up on the part of the Navy for failing to locate the original documents (which might, or might not settle the matter once and for all), that any logical assumptions as to its authenticity is still in doubt, despite the passage of time.

The National Cryptologic Museum has all the records on the Pearl Harbor attack of December 7. They have all the lead up to the Japanese prior to the attack as we as many other records.

If we look at Roosevelts Record going back to 1940 he provided aid to Great Britain and Russia to keep them in the was against Hitler. He had 160 tons of gold retrieved from war purchase from South Africa to keep the UK in payments prior to Lend Lease being enacted by the US. He financed Russia for over a Billion dollars to pay for war materials until he could he could work with Lend Lease.

Another factor is that the Battleships in Pearl Harbor were basically obsolete well over 20 years old. There were two classes of battleships just completed, and another 4 ships of the South Dakota in construction. These were all modern and capable meeting the Japanese.

So is the insinuation the President wasn’t concerned about obsolete ships the correct interpetation of events leading up to the attack. The naval personnel were not obsolete, so was the decision basically to sacrafice the military personnel up to a certain point. Prior to the attack; on the morning of the 7th, Admiral Stark had ample oppotunity to alert Pearl Harbor but did not; the congressional hearings after the war made this very clear.

John, It is a myth that the battleships at Pearl Harbor were obsolete. Yes, they were 20-25 years old. However if you look at their upgrades & refits history before & after the attack, then you will see that the US Navy spent alot of money to keep them from becoming obsolete. Their slow speed was intentional, to maximize armor protection & reduce target size. They were fairly maneuverable and had good endurance, although they were fuel hogs. They were kept much more up to date than their peers in the Royal Navy.