By William F. Floyd, Jr.

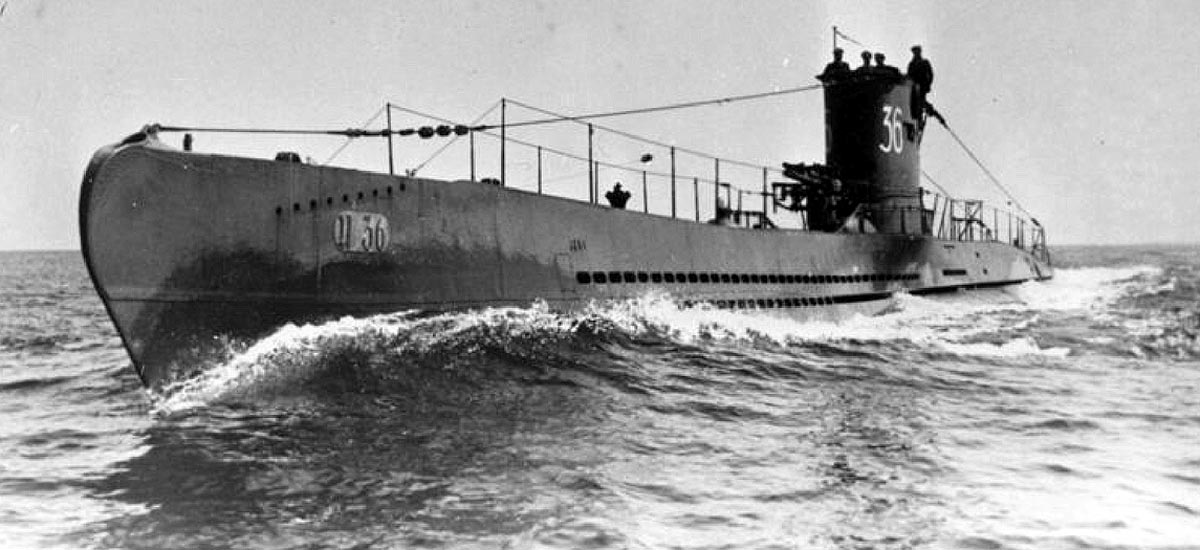

On the evening of October 13, 1939, the German submarine surfaced off the Orkney Islands in the North Sea. Lt. Cmdr. Gunther Prien, a promising U-boat commander, pulled himself up on the bridge. He soon discovered that, although weather conditions were near perfect, the Aurora Borealis had made its appearance, illuminating half of the horizon and threatening to make the boat’s presence known. This was the first command for the 31-year-old Prien, who had been chosen by Rear Admiral Karl Dönitz, head of the German submarine force. Prien was to carry out the first special U-boat operation of the war, an attack on the British fleet at its home base of Scapa Flow.

This story was first published in Military Heritage. Order your subscription here!

On October 8, U-47 had left her mooring in northern Germany bound for the North Sea. After Prien revealed the mission to the crew, the U-47 slipped into Holm Sound, one of the entrances to Scapa Flow. By 12:30 AM, October 14, the boat was inside Scapa Flow. At first Prien was able to make out the shapes of several destroyers, but then he spotted the battleship HMS Royal Oak and the seaplane carrier HMS Pegasus. U-47 was now about 4,000 yards from her intended target and was in position to attack.

A Cold Victory

The bow torpedo tubes were aimed, and the order to fire was given. Three minutes later, one of the torpedoes exploded harmlessly against either the bow or anchor chain of the Royal Oak. Puzzled, Prien turned his craft around and discharged a stern torpedo, which also missed its mark. Those aboard the Royal Oak thought the torpedo explosion was caused by an internal source, thus giving Prien a second chance. U-47 was again put into position to attack, and the torpedoes were fired. This time the Royal Oak was struck by a torpedo, and the harbor came to life. The Royal Oak soon sank taking 833 of her 1,234 officers and men down with her.

The submariners were exultant, but their worst ordeal still lay ahead, which was to escape unscathed. The tide was running against them, and even at full power U-47 moved along at only slightly more than one knot. A searching destroyer was drawing near, her searchlight probing the darkness but failing to locate U-47 as it made its way into Holm Sound. Soon U-47 slipped back into the North Sea. “The glow from Scapa Flow is still visible,” wrote Prien in his log. Two weeks later, Gunther Prien and his crew were the guests of Adolf Hitler in Berlin.

At the Chancellery, Prien was decorated with the Knights Cross.

Winning the German U-Boat Numbers Game

According to the terms of the Versailles Treaty, Germany was barred from having submarines. However, when Germany decided it could no longer abide by the treaty, one of the first steps it took was to rebuild its vaunted submarine force. In 1934, the greatest submarine fleet the world had ever known was reestablished.

In the end, the defeat of the U-boats really came down to a numbers game. The strategic goal of the German U-boat force was to sink more shipping than the Allies could replace and force surrender through starvation. This was a fight the Germans were sure to lose. In 1943, its U-boats destroyed 6.14 million gross registered tons of Allied shipping. Over the same period, American shipbuilders alone delivered 18 million tons of new merchant ships for the war effort, four million more tons than the Germans sank during the entire war. The gap in tonnage gained versus tonnage lost would continue in 1944 and 1945.

Although the U-boats were failing to sink as many Allied merchantmen to sustain the tonnage war, the U-boat crews were perishing in droves. The German goal of isolating Great Britain from the rest of the world, particularly the United States, was bound to fail. Even though the United States was not actually in the war when Germany started sinking merchant shipping, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had no intention of letting Nazi Germany defeat Great Britain. It would have been a disaster of major proportions in that the Allies would have been denied a staging area close to France for the invasion of Fortress Europe and would have, without question, lengthened the war and cost many more lives.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments