By Christopher Miskimon

Historians often compare Adolf Hitler to a gambler. He kept making risky bets that paid off time and again—until they didn’t. Poland was one example because it led to general war. What brought Hitler to take this risk? With the benefit of hindsight it is seen as enormous, but what did the situation look like to the German Führer and his closest advisers at the time? The popular modern view of Hitler is that of a raving lunatic, screaming at subordinates while pushing phantom armies around a map in his bunker. While he deserves every negative epithet given him, he did not decide all his strategic and operational decisions from mad, angry rants. In the years leading to World War II there were numerous events that took him down the road from a promise to rebuild the nation to inevitable conflict. However skewed, there was method to his madness, which came close to paying off in the early years of the fighting. The war officially began with the Nazi invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, but numerous factors led to this attack.

Logic, Planning, Revenge: Why Hitler Targeted Poland

While many of the calculations for war were based on some modicum of logic and reasoned planning, revenge, the basest of human emotions, played its part. German humiliation over the conditions placed upon the nation at the end of World War I had not abated in the two decades since the conflict ended. Over time the mass emotional reaction to the treaty stipulations became a festering sore among the population. This wound was ripe for exploitation by the Nazi propaganda machine during the party’s rise to power.

The Treaty of Versailles imposed severe restrictions on the German military. The ground forces were limited in size to 100,000 troops in 10 divisions, including 4,000 officers. The Army could be used only for the “internal maintenance of order” and defense. Also prohibited were staples of the German military system, such as a general staff, most officer training schools, and any sort of reserves or paramilitary groups. Additionally, tanks and heavy weapons were denied. Chemical weapons were expressly forbidden. Defensive positions along the east bank of the Rhine River had to be demolished for a distance of 50 kilometers from the riverbank. The west bank was similarly denuded of defenses. This left the country defenseless against attack.

The humiliation of Versailles went beyond just military limitations. Germany lost land to Poland and France. The French received Alsace-Lorraine, lost decades before during the Franco-Prussian War of 1871. The “Polish Corridor,” a strip of land given to Poland granting it access to the Baltic Sea, meant East Prussia was now physically separate from the rest of the country. The formerly German city of Danzig was made a “Free City,” controlled by the Poles despite its largely German population. All of Germany’s overseas colonies and territories were transferred to other nations. Last was a crushing debt of reparations, equivalent to billions of dollars today. (Read more about the conflicts and events that led to the Second World War inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

The cumulative effect of the treaty requirements created a sense of injustice among the German populace, which the Nazis were all too willing to use in their grab for power. The party came into power on a promise to right the wrongs of Versailles and make Germany strong again. Germany suffered many internal troubles throughout the 1920s and early 30s, something the German people remembered. Once national power was restored in the late 1930s, it became a natural, brutal progression to use that power against nations that had taken German lands. The Polish Corridor stood out in particular; regaining it meant reconnecting East Prussia to Germany proper.

With revenge in mind, the next step for Hitler was rearmament. This was the key prerequisite for any resurgence of Germany as a major power. Even before Hitler began rearmament in late 1933, the military had been secretly preparing for a fast expansion through a combination of training, liberal interpretation of the treaty restrictions, and secret weapons development projects. This allowed the Nazis to quickly create a massive military machine, faster than Germany’s opponents thought possible.

Initial steps included rebuilding the German arms industry so it could produce the necessary weapons. The plans for fast wartime expansion of the Army were instead applied to peacetime growth. The first increase was to 300,000 troops in 21 divisions. This program was to be finished by 1937, but Hitler advanced this timetable to the fall of 1934, barely a year later. During this period Hitler began to consolidate his power, moving against men like Ernst Röhm, the leader of the Nazi Party’s paramilitary arm, the Sturmabteilung (SA). He also absorbed the powers of the military commander in chief when the German President Paul von Hindenburg died in August 1934. Afterward German soldiers and sailors were required to swear an oath of allegiance to Hitler personally, a throwback to the oath given the kaiser during the imperial period. By the end of 1934, German Army strength reached 240,000.

On March 16, 1935, Hitler publicly rejected the Versailles Treaty and ordered a further expansion of the army to 36 divisions under a new defense law. Conscription was also reintroduced. Within two months another law created the Luftwaffe. The conscription program created a large pool of trained manpower, something the Germans lacked due to Versailles. Changes at the command level also made the German military more effective. The Reichswehr was renamed the Wehrmacht, with the three branches called the Heer (army), Kriegsmarine (navy), and Luftwaffe (air force). The general staff was rebuilt, and Hitler was solidly placed as the military’s supreme commander. Generals who disagreed with Hitler were retired or removed through scandal or accusations of misconduct. The Führer created a modern, powerful force completely under his control.

While this buildup was touted as smooth and organized with Teutonic efficiency, the process was difficult. German industry needed time to create modern weapons, most of which were only designs on a drawing board. Raw materials, trained labor, and factory capacity were insufficient to provide for all three services’ needs. The navy took a back seat to the Army and air force. This decision made sense because Germany’s primary opponents bordered the nation, rendering a powerful fleet unnecessary in the short term.

Making it Up as they Go: The Rapid Expansion of the Nazi German Army

Building on its secret experiments, the Army started an ambitious program for armored vehicles, but they were learning as they went. The first models were lightly armed and armored vehicles, which would later prove inferior to enemy tanks, though the Germans usually handled theirs better. Without making sacrifices elsewhere, it was impossible to build as many vehicles and artillery pieces as were needed. Hitler was unwilling to strain the peacetime German economy, so production rates were kept low.

The rapid expansion also placed a strain on personnel. There were not enough qualified officers and NCOs to fill all the required billets. Fast promotions and the recall of World War I veterans alleviated these problems, but only to a limited extent. Many of the veterans were getting too old for field service and needed refresher training. Many officers were lost to the newly formed Luftwaffe, and many staff officers for air units were ground forces men untrained and inexperienced in air operations. Another quick solution was to militarize entire police units to capitalize on the training and discipline of their NCOs and officers.

Despite these difficulties, rearmament did produce results. By October 1937, the army reached an active strength of 39 divisions in 14 corps, including three panzer and four motorized divisions. There were 29 divisions in reserve with more of their soldiers having recent training through the conscription program. In 1938, a dozen more divisions, including two panzer and four motorized, were also formed along with 22 more reserve divisions. Some of these units came from the absorption of the Austrian Army, which occurred that year. Further expansion occurred in 1939.

Possessing a powerful army gave Hitler options in the expansionist risks he took. Like many Germans, he sought revenge for perceived injustices. For the Führer the scales could only be balanced through war, and a strong military made war feasible, even desirable, as it would prove Germany was again formidable and to be respected. By 1939, the Army had 102 divisions, half of them active. Total strength was around 1.8 million troops. While there were still shortages in certain types of weapons and equipment, the Nazi propaganda machine had done its work, and these shortcomings were not apparent. Foreign observers saw a formidable modern force, and Hitler was happy to let them believe that image.

Prior to the Polish Crisis, Germany had gotten extensive practice in territorial acquisition, though without war. Instead, political maneuvering and bluff achieved Nazi goals up to that point. There was tension; war clouds loomed over Europe for several years before September 1939. However, until then each crisis had been resolved in Germany’s favor, a winning streak that increased confidence within the Reich in its own ability and the moral cowardice of its opponents. Hitler was susceptible to a gambler’s faith in a winning streak, and this was a factor in the Nazi invasion of Poland.

The Saar, 1935: Nazi Aggression Takes its First Steps

The Third Reich’s first success came in the Saar in 1935. This region of Germany was placed under Anglo-French occupation and control in 1920 for a period of 15 years. The Saar was an industrial center and contained coal fields that were given to France. A commission oversaw the territory until 1935, when a plebiscite was held to determine what would happen to the area. The situation was a reminder of German defeat in World War I and another territory stripped from the nation despite the ethnically German citizens in residence.

Once the Nazis came to power in 1933, large numbers of Germans who opposed their rule moved to the Saar precisely to escape them. Over the next two years, as the plebiscite grew near, these opponents of Hitler’s regime campaigned to have the region remain under French occupation. The Führer had other plans, as regaining the Saar would be a propaganda victory for his government. He directed Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels to conduct a media campaign aimed at swaying the populace to vote for return to the Reich. When the vote came in January 1935, over 90 percent of the voters chose to return to Germany. On March 1 the Saar became German again. With German reoccupation came the arrest of those considered to have collaborated with the French government and Nazi opponents who had fled there previously. Regaining the Saar was a first step for Nazi aggression.

The following year Hitler went further and reoccupied the Rhineland. The demilitarization of the area was stipulated in the Versailles Treaty and made permanent in the Locarno Treaty of 1925, which sought to normalize relations between various European powers. The Rhineland was occupied by Allied troops until 1935 under the terms of the treaty. In actuality these troops were withdrawn by 1930. Over the next five years, as the Nazis came to power and more openly disregarded the Versailles Treaty, German reoccupation of the Rhineland became an expected development, calculated to cause a crisis.

Hitler’s Annexation Gambles in the Rhineland, Austria, and the Sudetenland

In early 1936 Hitler gambled and sent a small force into the demilitarized zone. Hitler knew there was a possibility of war but deemed it minimal; when War Minister Field Marshal Werner Von Blomberg expressed his fears, Hitler told him German troops would be withdrawn if French forces entered the Rhineland. The Reich went ahead with the move on March 7, 1936, sending a handful of infantry battalions into the Rhineland, where they joined local police and prepared for a French counterattack, planning a fighting withdrawal if necessary. When French troops stayed on their side of the border, Hitler’s confidence was bolstered, and he ordered the troops to stay.

Two years later Hitler made more moves that consolidated his nation’s position even further and reinforced his belief in the moral cowardice of the Western powers. In March 1938, Germany annexed Austria, incorporating its military into the Reich. There was a small pro-Nazi movement within Austria that was agitating for integration with Germany. This movement was suppressed by the Austrian government, which believed most Austrians wanted nothing to do with Hitler. On March 9, Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg announced a plebiscite to allow voters to state their preference about integration with Germany.

The Nazi propaganda machine went into full swing, announcing riots in Austria and unfair rules for the vote to sway the decision against integration. It claimed the uproar was a plea by Austrians for Germany to enter Austria and restore order. On March 12, Wehrmacht troops crossed the border, meeting no opposition. Hitler himself entered Austria that evening. Within days the union of Germany and Austria, known as the Anschluss, was announced. Hitler had once again increased German power without a war.

The second Nazi move of 1938 was the annexation of the Sudetenland. This event, the result of an agreement meant to maintain peace, was a major step toward the conflict to come. After obtaining Austria with such relative ease, Hitler turned his gaze toward the north-northwestern area of Czechoslovakia, a region known as the Sudetenland. Many ethnic Germans lived in this area, making it a good target for expansion. The usual propaganda claims were made, stating the Czech government was abusing ethnic Germans within its borders.

The Czechs prepared for war, but no one else did. Hitler met with representatives of Britain, France, and Italy in Munich during late September. There, he obtained an agreement from those powers to give the Sudetenland to Germany. Without support, Czechoslovakia had little choice but to acquiesce. German troops entered the Sudetenland to the applause of its Germanic populace.

Supposedly this was Germany’s last territorial demand; returning from Munich, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain made his now infamous statement of having achieved “peace with honour” and “peace in our time.” That peace lasted less than six months; on March 15, 1939, the Wehrmacht marched into the rest of Czechoslovakia. Appeasement had failed, and Hitler had Poland in his sights. With Czech territory in German hands, a Nazi invasion of Poland could proceed from both the west and south, making that nation’s defense more difficult.

Planning the Nazi Invasion of Poland

The Polish Crisis began 10 days after the Nazis took Czechoslovakia. Hitler ordered the Wehrmacht High Command (Oberkommando Der Wehrmacht, OKW) to prepare a military campaign against Poland. He tried obtaining concessions from the Poles regarding Danzig and the Polish Corridor, including threats of military action. The efforts proved futile as the Poles refused to give in. Both sides began aggressive propaganda campaigns, with the Nazis claiming Polish atrocities against Germans in the corridor area.

Given his string of successes, Hitler was willing to gamble on Poland, although the situation in 1939 was worse than in earlier years. Unlike at Munich, there was no agreement with France and Great Britain for a resolution, and previous German actions had destroyed trust in Hitler’s word. The Third Reich’s racist policies and actions were also turning world opinion against it. Other members of Hitler’s civilian and military hierarchy were unwilling to express resistance to his plans. The Nazi leader had decided on another risky gamble, and with his absolute control there was no one to stop him.

With the decision made, a plan had to be created. During April 1939, OKW issued its annual directive to the armed forces. Within it was Fall Weiss (Case White). The plan was introduced with a statement from Hitler himself describing current relations with Poland. It required the German military to be prepared to attack by September 1. The plan stressed surprise. Mobilization would not take place until just before the actual invasion. Only regular Army units would be used at first, since calling up reserves would alert the Poles.

These active units would be secretly moved into assembly areas along the frontier before being ordered into their jumping-off points. The Army could also attack from Czech territory. There were also arrangements for defending the border with France, the Baltic Sea area, and German airspace. All this would effectively isolate Poland from her Western supporters until it was too late.

On April 28, Hitler nullified the German non-aggression treaty with Poland and demanded resolution on the Danzig issue. German operatives were sent into Danzig, where they attacked a customs house and tore down Polish flags. Polish actions against ethnic Germans were given wide press coverage. There was a Nazi faction in Danzig, and it clamored for return to Germany. This was the beginning of a months-long campaign to pave the way for German goals, with or without war.

Diplomatic Machinations and Nazi Propaganda

Over the following months further diplomatic machinations took place. On May 22, a pact was signed with Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, taking pressure off Germany’s southern flank. However, Hitler assured Mussolini there would be no war, and the Italians made no promise of military support. This kept Italy from the Allied camp and threatened France’s and Britain’s Mediterranean holdings. Hitler also received visits from the leaders of Yugoslavia, Hungary, and Bulgaria. These affairs were accompanied by extravagant displays of German military power, with scores of aircraft roaring overhead or hundreds of tanks clanking past.

A major victory for the Nazis was the rapprochement with the Soviet Union. The British and French were seeking a tacit alliance with the Soviets as a counterbalance to Germany, but this new development quashed that hope. Russia and Germany secretly negotiated an agreement for respective spheres of influence. The Soviets would have a free hand in Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia along with eastern Poland. In exchange, Germany would regain Danzig, the Polish Corridor, and western Poland.

Openly, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression treaty between the nations. This was a surprise development as the Nazis were staunchly anti-communist. Both Hitler and Stalin still expected eventual war; the Soviets expected conflict as early as 1944. While war would come much sooner with the German invasion on June 22, 1941, in August 1939 the issue seemed settled.

The Polish Crisis came to a head in August. The Germans placed more pressure on Poland over Danzig and the corridor, with civil disturbances taking place. The Poles stood firm, bolstered by assurances of support from France and Britain. On August 12-13, Italian Foreign Minister Count Galeazzo Ciano met with Hitler to discuss a diplomatic solution. Italy did not want its ally going to war; the nation was still recovering from its campaigns in Albania, Ethiopia, and Spain and was not ready to fight the French and British. The Italian military needed time to modernize its forces and did not expect to be ready until 1942. Hitler, confident in his course, would not be swayed. Ciano felt the Germans had breached their agreement, but there was little to be done.

On August 17, the Nazis enacted their scheme to justify invasion. The Wehrmacht supplied Polish Army uniforms to operatives commanded by senior SS officer Reinhard Heydrich to create incidents of Polish attacks on German soil. Hitler addressed his military leaders about the issue on August 22, admitting an incident would be “arranged.” The morality of such an act was irrelevant; only victory mattered. He thought it unlikely the British and French would intervene, and if they did they could not reinforce Poland directly. If war came, Germany would win. Hitler also mentioned the impending treaty with the Soviets, which was signed the next day. The speech ended with a statement of belief that the Wehrmacht could carry out any order successfully.

When the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact became public on August 23, it seemed war was inevitable. Hitler ordered the attack to begin on August 26. The next day the British sent Poland a written guarantee that Britain and France would come to its aid if Germany invaded. When he learned of the move, Hitler rescinded his attack order and engaged in a last-minute move to forestall the involvement of the Western Allies. He promised to respect the current borders with France and to support the British. This offer did not impress either nation, which had no reason to trust such promises. Negotiations were essentially broken off.

Nazi Germany Declares War on Poland

On August 31, Hitler signed the order for the Nazi invasion of Poland, to begin the next morning at 4:45. At 8 pm on the night before the invasion, Germans in Polish uniforms “captured” a German radio station in Silesia. A broadcast in Polish announced an attack on Germany. Soon German police subdued the “attackers.” Casualties were found dressed in Polish uniforms, but they were actually condemned German criminals. Within hours the full might of the Wehrmacht was thrown against the Poles.

When the invasion of Poland came, the Wehrmacht pursued a plan to envelop and destroy the Polish Army west of the Vistula and Narew Rivers. The main blow came from Army Group South under Generaloberst Gerd Von Rundstedt, striking northeast out of Silesia toward Warsaw. A secondary thrust would come from occupied Czechoslovakia to handle Polish troops in Galicia. Generaloberst Fedor von Bock’s Army Group North would strike east through the Polish Corridor to link with East Prussia. That done, Bock would then advance on Warsaw from the north.

Polish plans were for a forward defense in western Poland. This was required; much of the Polish Army was made up of ethnic Poles who lived in the western part of the nation. They would need time to mobilize. A quick defense would hopefully also draw Britain and France into the war sooner. It was an imperfect plan, as it allowed the Poles to be decisively engaged early in the fighting. Polish units would also have to cover more territory than was prudent. Combined with Allied underestimation of Germany’s new army and tactics, it was a recipe for defeat, though in fairness the Poles were in a bad position no matter what plans they enacted.

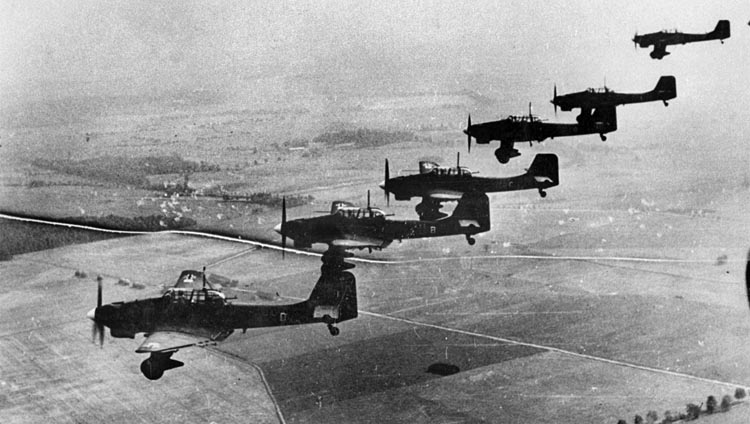

Despite all the mobilizations and signs, the attack was a tactical surprise for the Poles. The Luftwaffe commenced bombing while the old German battleship Schleswig-Holstein began shelling the Polish fortress at Westerplatte. The Polish Navy was attacked and would be effectively destroyed within a few days. The advancing ground troops swept aside a few Polish patrols and border guards and moved into Poland itself. Paramilitary troops from both sides engaged in a vicious struggle for Danzig.

The Polish Corridor was defended by two infantry divisions and a cavalry brigade. The German 4th Army attacked, and the Polish cavalry fought a series of delaying actions, including a raid that resulted in a cavalry charge against a surprised German infantry battalion. They were only beaten off with the arrival of a few armored cars. The next day Italian war correspondents were brought to the scene. They reported being told the Polish cavalrymen had been killed while charging German panzers. The story took hold of the popular imagination until it became an accepted reality, but the tale is just a myth.

As 4th Army hit the Polish Corridor, 3rd Army advanced out of East Prussia toward Warsaw. Two corps attacked but ran into the Mlawa Line, a fortified zone guarding the obvious route of attack. The Germans tried to outflank the position, but swamps secured both flanks, bogging down the effort after several assaults failed. The Polish Mazowiecka Cavalry Brigade met the German 1st Cavalry Brigade along the Ulatkowka River. Engagements between mounted patrols soon led to heavy dismounted combat. By sunset of the first day of the war, 3rd Army was stopped cold.

Making the main effort, Army Group South saw extensive action, particularly with its 8th and 10th Armies in Silesia. They intended to strike against the Polish Armies Lodz and Krakow, get over the Warta River, and cut off enemy forces in western Poland. Afterward they would advance on Warsaw. These two Wehrmacht formations contained many of the German armored and mechanized divisions.

Initially fighting was light since the Polish defenses were 20 miles behind the border. The worst fighting took place when the 4th Panzer Division attacked the Wolynska Cavalry Brigade at the village of Mokra. The horsemen were assisted by an armored train, while the Germans had trouble coordinating their tanks and infantry. A Stuka raid succeeded in destroying Polish supplies and killing many of their horses, but the cavalrymen held firm. High casualties forced them to finally retreat at sunset, with German tanks hounding them. Meanwhile, Army Krakow suffered badly, its 7th Infantry Division being cut off and overwhelmed by several German divisions. The fortified city of Katowice fared better, however, limiting German success. The rear areas were threatened by guerrilla units of ethnic Germans formed by German intelligence before the war.

Advancing from Slovakia, the 22nd Panzer Corps got around the Polish border units manning the Dunajec Line, forcing Army Krakow to deploy its 10th Mechanized Brigade. The attack was stopped only when the Polish 6th Infantry Division was also committed. Two German mountain divisions attacked across the Carpathian Mountains against Army Karpaty, but the terrain kept them from making any gains.

The Luftwaffe tried to destroy the Polish Air Force on the ground, but most of it was already dispersed to auxiliary fields. Despite more myths, only 24 Polish combat aircraft were destroyed on the ground during the entire campaign, though many trainers and unserviceable planes were destroyed. The Luftwaffe also hit railways and important roads in preplanned attacks. Also contrary to legend, the Germans were not yet capable of hasty close air support missions. In the days to come more planned targets were hit, and Polish troop movements were successfully interdicted, hampering the mobilization of reserves. A few close air support missions were attempted late in the campaign.

A bombing attack on Warsaw took heavy losses to the fighters of the Polish Pursuit Brigade on the first day of the war, but Luftwaffe numerical superiority enabled repeated strikes and by September 6 the Polish unit had lost 70 percent of its fighters, forcing its withdrawal. The rest of the Polish fighter strength was used up in the skies over the main fighting, inflicting at least 126 losses on the Germans. Polish bomber crews flew bravely against the advancing German armies but likewise suffered terribly for little effect.

Back in the north, the Wehrmacht continued advancing along the corridor while Polish forces withdrew southward, leaving the Westerplatte garrison cut off. In the Tuchola Forest, the 3rd Panzer Division managed to cross the Brda River. Two German divisions also advanced west down the corridor from East Prussia, nearly trapping the Polish units between them. Only one Polish division was able to escape the encirclement on September 3. The Germans kept up pressure on the Mlawa Line, finally starting to outflank it. The beleaguered Polish cavalry was reinforced with the 8th Infantry Division but could not hold the line any longer. By the next day the Mlawa defenders and the remaining Poles not encircled in Pomerania were ordered to withdraw to the Vistula Line.

During the night of September 2, the Polish Podlaska Cavalry Brigade conducted a raid into East Prussia, the only Polish attack on German territory. It withdrew after some skirmishes with German militia. The Polish 20th Infantry continued manning the Mlawa Line to allow their comrades to withdraw. It was soon surrounded but continued to resist. Army Modlin tried to hold at the town of the same name, but German river crossing operations threatened the Polish position. After a failed counterattack, the Poles withdrew again across the San River. Another Polish garrison tried to delay the Germans at Modlin but was also surrounded by the advancing Nazis.

The German army groups now began their encirclement of Army Poznan in western Poland. Army Poznan’s commander, General Tadeusz Kutrzeba, asked to attack the German 8th Army, the northern formation of Army Group South. He was refused permission by Marshal Edward Rydz-Smigly, supreme Polish commander, who feared the unit would be destroyed; he wanted to avoid a decisive battle west of the Vistula. Sadly, the Germans were vulnerable on this flank and feared just such an attack.

The Polish 7th Division, decimated earlier, was mauled again by the 1st Panzer Division and several infantry units as the Germans exploited the gap between the Polish Armies Lodz and Krakow. This fighting enabled the German 10th Army, with its heavy armored contingent, to move toward Warsaw. The tanks struck out across flat farmland through the heart of Poland. The Polish units south of this exploitation withdrew skillfully, delaying the 2nd Panzer Division and maintaining their cohesion.

The panzer divisions made for Warsaw directly toward the Polish Army Prusy, which had been placed there in expectation that the Germans would advance from that direction. Containing three infantry divisions and a cavalry brigade, this army also had a small force of tanks to defend against the panzers bearing down on them. The 1st and 4th Panzer Divisions quickly made for Piotrkow, where they were met by Polish infantry and the 2nd Tank Battalion with its 7TP light tanks. The Polish tankers fought well, knocking out 33 German armored vehicles, but since they were not concentrated their efforts had no lasting effect.

Meanwhile, the German 10th Army pushed back Army Krakow to Kielce by September 5, further opening the path to Warsaw. General Kutrzeba again asked to attack the German flank but was refused. That evening Marshal Rydz-Smigly ordered all four engaged Polish armies—Poznan, Prusy, Lodz and Krakow—to withdraw to the Vistula.

The Germans noticed the Polish moves; Rundstedt and other field commanders realized what was happening and asked to penetrate deeper to encircle the Poles. OKW still worried about a French attack in the west, however, and delayed. It took until September 9, when it was becoming obvious the French were not moving quickly, for the high command to change its mind. Meanwhile, the Poles continued retreating to the Vistula. Rydz-Smigly became worried that the fast-moving Germans would cut off his forces and decided to move his headquarters forward to Brzesc. This location was not able to handle the level of communications needed, and the move proved a major error as the high command could not effectively communicate with units in the field.

The fast-moving German units were easily outdistancing the Polish forces now; time and again Polish troops reached a position only to find German tanks behind them. The gap between Army Prusy and Army Lodz was the worst, with the 1st and 4th Panzer Divisions pushing ever deeper toward Warsaw. Other German forces were moving through the Polish Corridor for another offensive. General Bock was allowed to push his troops down the east bank of the Vistula to endanger the Poles defending along that line.

With the Germans closing on Warsaw, Marshal Rydz-Smigly finally began to consider the counterattack General Kutrzeba was suggesting, hoping to relieve pressure on Army Lodz and allow the Poles time to reorganize around Warsaw and the Vistula River. The counterattack came along the Bzura River on September 9; the Germans were still aware of the vulnerability of their flank but were lulled by bad intelligence reports and the lack of Polish movement up to this point. Three Polish infantry divisions (14th, 17th, and 25th) attacked the German 24th and 30th Infantry Divisions. A pair of Polish cavalry brigades guarded the flanks of the advance. The initial fighting was heavy, but the Poles threw in their reserves supported by armor and turned the tide. Both German divisions fell back; the 30th lost more than 1,500 as prisoners by September 10. The Poles were finally striking back.

Rundstedt remained calm and ordered the 1st and 4th Panzer Divisions to turn west from the outskirts of Warsaw and begin encircling Army Poznan. He hoped to cut off and destroy this large concentration of enemy troops. Other units were also rushed to the area, establishing numerical superiority. Within two days the Polish offensive was done, and Kutrzeba was ordered to break through to the south toward the Romanian border. However, his command was now badly outnumbered, nine Polish divisions with two cavalry brigades against 19 German divisions, of which five were armored or mechanized.

Kutrzeba understood his predicament and instead moved eastward. The Germans attacked, but the fighting proved difficult until air support arrived. On September 16, some 820 Luftwaffe planes attacked along with the 16th Panzer Corps on the ground. By that evening Kutrzeba ordered his troops to try and escape the pocket through a gap at Sochaczew. Elements of two divisions and two cavalry brigades made it out, but 120,000 Poles were taken prisoner when the Bzura Pocket capitulated on September 18. Both Army Poznan and Army Pomorze were destroyed. Their sacrifice had delayed the German advance on Warsaw and allowed their comrades to prepare better defenses, but the price was staggering.

The Polish command was operating in confusion as stragglers and partially mobilized units began arriving, not knowing where to go. The Polish leadership within Warsaw decided to make a stand and defend the city. Since Rundstedt’s Army Group South was still fighting at Bzura, Army Group North attacked the city on September 15. It was led by the German 3rd Army, which had troops on both banks of the Vistula. The Germans entered the suburbs of the city and engaged in heavy fighting, but since Warsaw was not yet surrounded some Polish troops were still filtering in. After September 21, the Germans finished mopping up the Bzura Pocket and redistributed divisions to surround Warsaw. Army Group South spread out along the south and west sides of the city.

The Soviet Union Moves in, Sealing Poland’s Fate

On September 17, Polish fortunes reached a new low when the Soviet Union moved into Poland with 41 divisions and 12 tank brigades totaling over 466,000 troops. Some Poles expected the Soviets might be coming to assist them, but those hopes were quickly dashed. Most of the Polish Army was fighting to the west, leaving only token border troops on the eastern frontier. On average, there was one Polish battalion against a Soviet corps. There was some fighting, mostly skirmishing, but all real hope was now lost. Marshal Rydz-Smigly ordered all Polish units to make for the Romanian border.

On September 23, the Germans began their first attempt to take Warsaw, supported by 1,000 field guns, but few gains were made. The Poles were resisting fiercely. On September 25, another attack came with both artillery and air bombardment. Known as “Black Monday,” the city was pelted with bombs and shells. Even German Junkers Ju-52 transport planes were pressed into service, dropping many incendiary bombs. There was so much smoke that target identification was almost impossible, and many Luftwaffe aircraft dropped their payloads on German troops.

The next day the Germans seized three old forts on the south side of Warsaw. To increase the suffering within the city and hopefully speed the surrender, Hitler ordered that no civilians were allowed to leave, trapping them inside the shattered capital. During the evening of September 26, Army Warsaw’s commander, General Juliusz Rommel, sent word to the Germans that he was prepared to discuss surrender. The fighting ended the next day, and more than 140,000 Polish troops became prisoners. A separate Polish force at Modlin held out for another two days, and then it too gave up, 24,000 soldiers marching into captivity.

A small Polish force, east of Warsaw and out of communication, was unaware of the city’s surrender and tried to get there to join the fighting. It ran into the German 13th Infantry Division, a motorized unit, and fought until October 6. Since by this point the Soviets had invaded eastern Poland, there was no longer anywhere for Polish troops to go, and the campaign was effectively over.

Hitler’s great gamble for a Nazi invasion of Poland had succeeded at the cost of 48,000 casualties and a nation now at war. Further gambles would bring France, Denmark, Holland, Belgium, and Norway under his control by the end of 1940. It would be to the east, on the vast unending plains of the Soviet Union, where the gambles would begin to fail, leading to the ruin of the Reich Hitler had claimed would last a millennium.