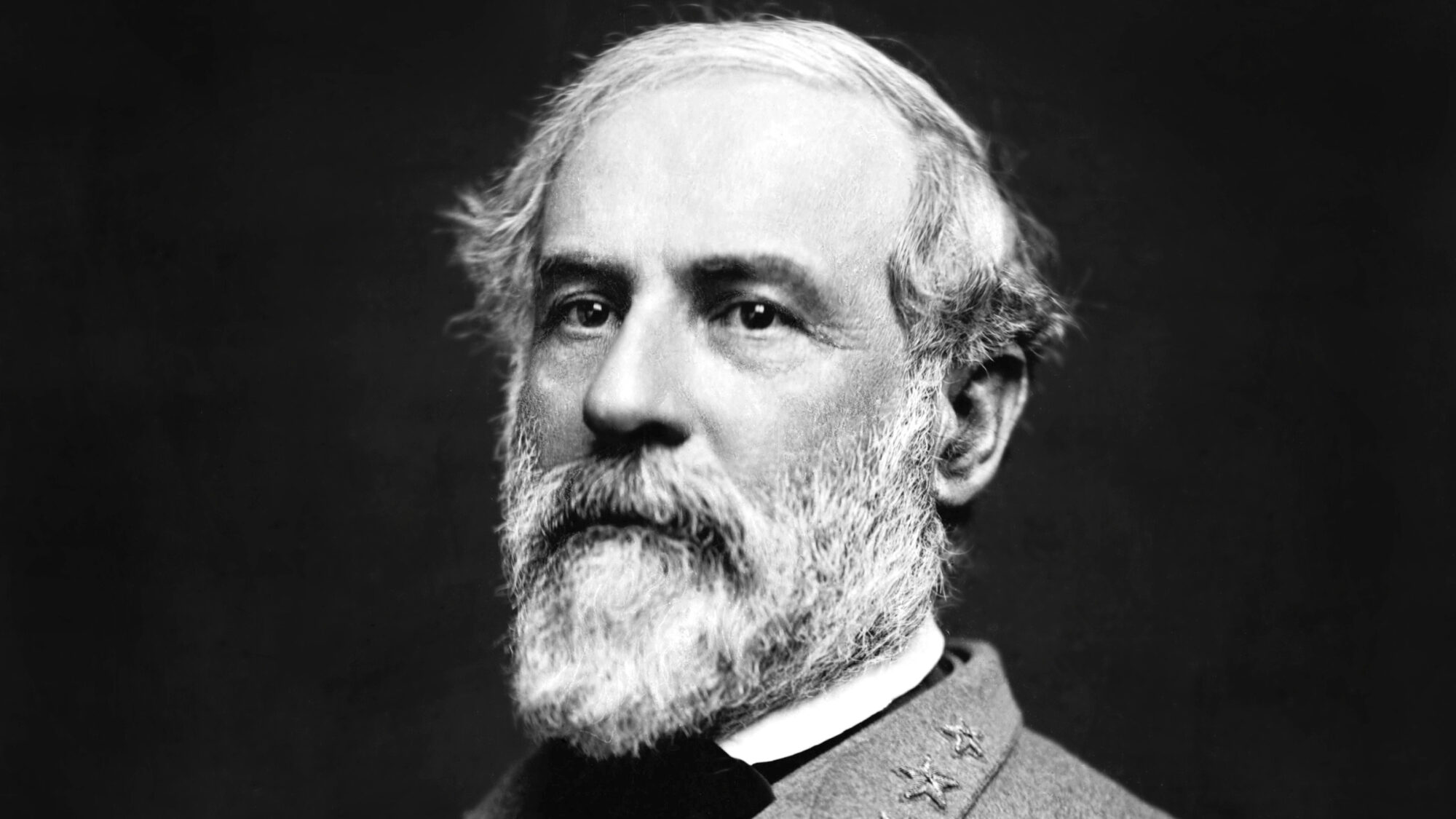

Robert E. Lee never knew his father, Revolutionary War hero “Light Horse Harry” Lee. True, he saw him a few times, on the infrequent occasions of the elder Lee’s visits to his family at their gloomy mansion, Stratford, in Westmoreland County, Virginia But Light Horse Harry, living up to his nickname, was never anywhere for very long—certainly not in the confining bosom of his family.

As his personal and political fortunes declined, Harry Lee wandered restlessly between Virginia and Washington, D.C., where he served for a time as a congressman and was the only Virginia representative to vote for Aaron Burr over fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson in the deadlocked presidential election of 1800. As usual, Harry was on the wrong side politically.

When Robert E. Lee was two years old, his father was sent to debtor’s prison in Montross, Virginia. By then, Harry had run up so many debts that he installed a chain across the front door at Stratford to bar his creditors—as if that would work. Neighbors laughingly told the story of how Lee once borrowed a friend’s horse. The friend, thinking to save Lee a trip, sent along a servant with a second horse to lead the first horse back home when Lee was done with it. Several weeks later, the now-bedraggled slave returned on foot. He told his master that Lee had sold both horses. “Why didn’t you come home?” the neighbor asked. “Because General Lee sold me, too,” said the slave.

While her husband was away serving time in the Montross jail, Robert E. Lee’s long-suffering mother, Ann, gave up the Stratford mansion and moved herself and her four children to a small house in Alexandria. Family legend said the three-year-old Robert spent a long time saying goodbye to the two iron angels molded into the fireplace in his mother’s ground-floor bedroom.

Harry Lee hoped to revive his flagging fortunes by publishing his memoirs, but the book, loaded with anti-Jefferson propaganda, did not go over well in Virginia or the rest of the country. His Federalist Party leanings ran counter to the pro-Republican sentiments of most of his fellow Virginians, and indirectly led to his death after he was seriously injured in the infamous Baltimore riot of 1812 while defending his Federalist editor-friend Alexander Hanson.

Robert E. Lee saw his roving father for the last time when he was six as Harry Lee boarded a ship at Alexandria and sailed off down the Potomac to regain his health in more temperate Barbados. Ironically, one of his political enemies, Secretary of State James Monroe, had intervened diplomatically to help Lee emigrate. He no doubt was happy to see him go.

The lingering effects of the beating he took at the hands of pro-Republican Baltimore rioters, as well as a life of profligate dissolution, caught up with Harry Lee when he was returning to America from Barbados in the spring of 1818. Going ashore at Cumberland Island, Georgia, Lee suddenly sickened and died at Dungeness, the plantation home of his late Revolutionary War comrade Nathanael Greene. He was buried on the grounds by virtual strangers.

Robert E. Lee visited his father’s grave for the first time in 1862, 44 years after Harry’s death—a revealing statistic in itself. By then, he had become a general in the Confederate Army, rebelling against the very government his father, a committed nationalist, had helped bring into being.

In contrast to his bon vivant father, the adult Robert E. Lee was a polite, reserved individual, careful with his money, his emotions, and his affections. When it came to generalship, however, Robert shared his father’s gambling nature, to the great and abiding sorrow of the Confederacy. He threw the dice twice, at Antietam and Gettysburg, invading the North and losing both wagers and, eventually, the war. Father and son, the Lees were born gamblers. Unfortunately for both, they couldn’t seem to beat the odds.

Roy Morris Jr.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments