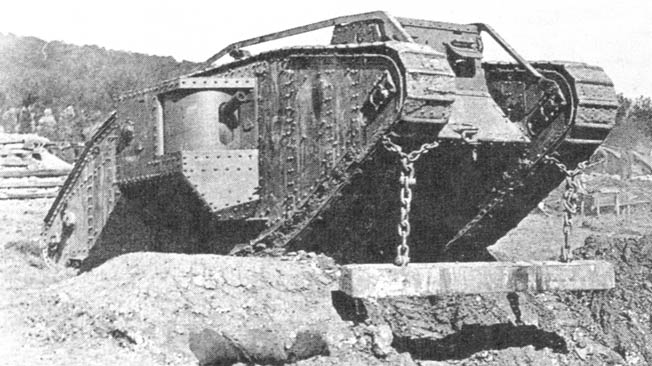

The “Mark IV” tank of World War I was rhomboidal in shape and came in two basic versions: male and female. The male version featured four machine guns and two 6-pounder (57mm) guns that were mounted on side extensions called sponsons. By contrast, the female version had only machine guns. Each vehicle was given a name corresponding to the letter designation of the battalion. For example, D Battalion tanks were named Deborah, Dominie, Devil May Care, Demon, and so on.

The tanks had a crew of eight, including a driver, commander, two gearsmen, two gunners, and two loaders. The crews were protected by armor that was up to 12mm thick—about a half an inch. Steel plates used for armor were cut and drilled before being hardened. They were then riveted to an iron frame. Crews developed real affection for their metal beasts, insisting that each machine had its own unique ways and personality. If a tank was badly damaged, a crew would be reluctant to transfer to another machine.

When Armored Warfare Was In Its Infancy

By 1917 standards, the Mark IV was a marvel of modern technology. It proved to be a very effective weapon when the ground was good, surprise was achieved, and infantry support was available. But armored warfare was still in its infancy, and the Mark IV was not without serious flaws. It was found that the male’s 6-pounder guns could only be used effectively if the tank was not moving. The vibration from the tracks—among other things—prevented accurate use of the gun’s sighting telescope.

What Made Life Inside a Mark IV Tank so Difficult

The 12mm armor was proof against most ordinary bullets, although sometimes the Germans had deadly armor-piercing rounds. The real danger was artillery shells, which could turn a tank into a flaming coffin within seconds. At 28 tons, the Mark IV’s great weight was too much for its engine, transmission, and suspension.

In action, a tank was its own self-contained hell. The noise was so great that commanders had to scream at the top of their lungs, and temperatures often reached over 100 degrees, regardless of the outside weather. The Germans learned to fire machine guns at a tank’s vision slits. Ricochets and molten pieces of bullet fragments—including white-hot pieces of the copper jackets—would spray particles into the tank, an effect crews mordantly called a “splash.”

Crews sat beside the engine and transmission. There were no firewalls or any kind of protection. In practice, that meant inhaling a nauseating cloud of vapors, a stench that included gasoline, carbon monoxide, oil smoke, and cordite from shells. Crews had to endure such conditions for as long as seven or eight hours at a time during a major battle. Sometimes crew members would pass out or become violently ill.

“Clan Leslie”, the tank shown in the photograph above, was a Mark I, not a Mark IV. The photo and caption should be replaced or removed.