By Mike Phifer

Two guns flashed and boomed from a British schooner, signaling the long-awaited invasion to end the rebellion in the American colonies. It was June 20, 1777 and the massive British and German army rowed their two hundred bateaux from Cumberland Head, near the Canada-New York border, out onto Lake Champlain. The flotilla, on that bright, clear morning, was an awesome spectacle to behold. Thousands of red- and blue-coated soldiers, their musket barrels glittering in the sun, moved down the lake, careful to keep their boats in formation. The Rebel watch boats that eyed the flotilla quickly scurried out of the British way and headed south to warn the American forces of the coming trouble.

Over a month previous, on May 6, the commander of the expedition, Lt. Gen. John Burgoyne, arrived at Quebec, with a plan that would sever the obnoxious New Englanders from the rest of the colonies and shower him with glory. The Grand Strategy to bring the uprising to a swift conclusion called for Burgoyne to lead an army from Montreal, up Lake Champlain (that is, south), capture Fort Ticonderoga then force his way down to capture Albany. There Burgoyne would rendezvous with a diversionary force under Colonel Barry St. Leger fighting its way east through the Mohawk Valley, and a third force under General William Howe pushing north up the Hudson Valley from New York City. With this conjunction completed and a line of strong posts secured from Montreal to New York City, New England would be isolated and the rebellion could be ended where it began.

Burgoyne’s Armada

Leading this backwater armada were four hundred native warriors in their birchbark canoes. Behind them came the Advanced Corps under Brigadier Simon Fraser: regulars from the 24th Regiment; light infantrymen and grenadiers from the other regiments accompanying the expedition, as well as three regiments remaining in Canada; two Loyalist units—the King’s Loyal Americans and the Queen’s Loyal Rangers; a company of marksmen under Captain Alexander Fraser; and 150 Canadian woodsmen.

Next came two tall-masted ships, Royal George and Inflexible, two schooners and the five other vessels, and 24 gunboats that made up the fleet. Rowing behind them was the British 1st Brigade under Brig. Gen. Henry Watsons, made up of the 9th, 47th and 53rd regiments. The brass came next in three pinnaces, or light sailing vessels: Burgoyne, Maj. Gen. William Philips—who commanded the right wing of the army, made up of the British Advanced Corps, 1st and 2nd brigades—and Maj. Gen. Friedrich Adolph Baron von Riedesel, who commanded the left wing of the army, made up the German Advanced Corps, 1st and 2nd brigades.

The British 2nd Brigade, composed of the 20th, 21st and 62nd regiments, under Brig. Gen. James Hamilton, rowed next.

Then came the Germans, contracted for the war from their feudal rulers back in their homeland. These were the Advanced Corps, consisting of grenadiers, dismounted dragoons, and jägers(riflemen) under Lt. Col. Heinrich Breymann; the 1st Brigade made up of the von Riedesel, von Rhetz and Specht regiments under Brig. Gen. Johann Friedrich Specht; and the 2nd Brigade composed of the Prinz Friedrich and Hesse-Hanau regiments led by Brig. Gen. W. von Gall.

Well trained and professional, the army numbered over seven thousand men, almost half of them German. Burgoyne’s army also had a large artillery assortment of 138 guns varying in size from 4.4-inch mortars to heavy 24-pounders. Lagging in the rear of the army were the sutlers and camp followers—soldiers’ wives, children and laundresses.

That night, encamped along the banks of the Bouquet River, Burgoyne penned an overly dramatic proclamation to be widely circulated in New England. Besides his military career, which started at the age of 15 as a junior officer and would see him rise through the ranks, taking him on active duty to Europe and America, Burgoyne also dabbled in writing plays for the theater. It was with this skill that he promised protection to the Loyalists and warned “the harden’d Enemies of Great Britain and America” of the Indian forces at his disposal and the vengeance they could wreck on those persisting in “the phrenzy of hostility.” The proclamation only brought anger and ridicule, in America and later in London. While at the same time threatening to set the natives loose on the Rebels, Burgoyne forbade the native allies from using bloodshed against old men, women, children or prisoners. The order fell on deaf ears.

The British Surround Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga, the “Gibraltar of the North” which played such a prominent role in the French and Indian War, would halt the British invasion from the north—or so hoped the Americans. Since 1776, the Americans had been repairing the star-shaped fort and fortifying Mount Independence, a rocky bluff a quarter of a mile on the opposite shore of the lake. With control of both these points and a boom of heavy timbers riveted together by bolts and reinforced with a double iron chain that spanned this narrow waterway, traffic on the lakes could be controlled. But to properly garrison the fortifications 10,000 men were needed—and the Americans had about 2,500.

The commander of Fort Ticonderoga, Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair, a former British officer, knew the enemy was on the move, but to what purpose he could not tell. Burgoyne’s Indians were successfully keeping American scouting parties from venturing too far into the woods. In frustration, St. Clair would write to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, commander of the American Northern Department, “No army was ever in a more critical situation than we now are.” St. Clair wrote too soon, for the situation was to get even more critical.

Three miles north of Fort Ticonderoga, on July 1, Burgoyne landed his forces. The German left wing disembarked on the east side of Lake Champlain, the British right wing on the west. There the soldiers pitched their tents for the night.

The next morning, Burgoyne set out to entrap the Rebels. Fraser’s Advanced Corps was to take the Rebel position at Mount Hope, located northwest of the fort, cutting off escape by Lake George. Riedesel was ordered to circle around Mount Independence and block “the Great Road” that ran from southeast of the Mount to Hubbardton, in what was then called the New Hampshire Grants and is now Vermont, and from which reinforcements might arrive. By 1 pm, Mount Hope was in British hands, after the Americans abandoned it and fell back to the “old French lines,” which consisted of log fortifications half a mile northwest of the fort. There would be no escape for the Rebels in that direction.

The Germans on the other side of the lake were having considerably more trouble in reaching their objectives. East Creek, which is more of a bog in places than a creek, blocked passage to Mount Independence. Forced to slog through a mosquito-infested marsh, Breymann’s Corps managed only to make 1,200 paces the first day.

Hacking a Road Up Mount Defiance

The next day cannons blasted from the fort, harassing the British, who were busy landing supplies and preparing for a siege. Dodging cannonballs, General Fraser surveyed the Rebel lines and noticed a glaring weakness. A mile southwest of the fort was Mount Defiance, which commanded both Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence. In 1776, some American officers had warned that this hill should be fortified, but nothing was done. A scouting party was immediately dispatched to reconnoiter the hill. It was found to be “very commanding ground,” which offered an excellent view of the Rebel positions.

The following day an engineering officer, Lieutenant William Twiss, determined a road could be built up the hill, allowing artillery to be brought up within 24 hours. General Phillips, who had 30 years’ experience as a gunner, took charge of the operation saying, “Where a goat can go, a man can go and where a man can go he can drag a gun.”

Hacking a road out of the “almost perpendicular ascent” of Mount Defiance, British soldiers and artillerymen, employing the army’s cattle, dragged two 12-pounders to the top of the hill. The Rebels were unaware of this threat, until the Indians built a fire on the hill, revealing the British position.

The Rebels Retreat

St. Clair immediately called a council of war. The jig was up. If the army was to be saved, they would have to abandon the fort and retreat south as soon as possible. At this point, the German troops, still laboring through the marshes, had yet to block the Great Road cutting off retreat to or reinforcements from the east. South Bay, the only water route available to reach Skenesborough located on the east side of the lake, was still open as well. It was decided that once darkness fell, the guns, supplies and wounded would be sent by water under Colonel Pierce Long to Skenesborough. St. Clair and the main body of the army would retreat along the road to Hubbardton, onto Castle Town, then west to Skenesborough to rejoin Long. Together, they would head south approximately 35 miles along Wood Creek to Fort Edward on the Hudson River south of Lake George.

All night, heavy guns from the fort opened up on the British lines to divert their attention. Sullen troops, angry over the idea of retreating, loaded two hundred boats with military supplies and baggage. Also climbing aboard the boats were wounded troops and camp followers. At 3 am, Long, with his New Hampshire Regiment manning the boats, slipped away from the fort.

St. Clair was doing his best to organize his army for the retreat. The militia companies would be placed between the Continentals to keep them from running off. The very capable Colonel Ebenezer Francis and his men would act as the rear guard. The plan for an organized withdrawal went up in smoke—literally, when General Roche de Fermoy, disobeying orders not to light fires, torched his headquarters on Mount Independence. The soldiers, fearing their retreat had been discovered, turned into a mob, pressing to get clear of the fort. The Continentals, better disciplined than the militia, were ordered by St. Clair to start the retreat single file.

British and German officers couldn’t help but see Fermoy’s headquarters burning in the early-morning light of July 6. The Rebels were up to something, but what? Three American deserters brought the answer to General Fraser. Quickly, Fraser dispatched a message to Burgoyne, then set off with a few men to investigate if the Rebels had really retreated. When he saw they had, Fraser ordered up his Advanced Corps.

The Advanced Corps Pursues the Retreating Rebels

They set out across the partially burned bridge that spanned the waterway between Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence. On the other side, they found a cannon loaded with grapeshot, ready to blast the British crossing the bridge. Fortunately for the British, the Rebel artillerymen decided to get dead drunk and lay passed out by the gun.

Setting out in pursuit, Fraser’s Advanced Corps struggled along the Great Road south. The road was no more than a narrow wagon track, plagued with potholes, ruts and stumps, hacked out of the forest that carpeted the rolling hills. The heat and mosquitoes made the march unbearable for the British troops, who sweltered in their wool uniforms and heavy packs. Conditions were no better for the Americans up ahead.

At about 1 pm St. Clair reached Hubbardton, which consisted of nine farmsteads. His bone-weary army had come 20 miles from Mount Independence and needed rest. For two hours St. Clair waited, hoping his rear guard would show up. Deciding he could wait no longer, he ordered Colonel Seth Warner to remain behind with his men and wait for the rear guard as well as Colonel Hale’s 2nd New Hampshire Regiment, who were still lagging behind. When they arrived, Warner was to take command and follow the main army south to Castle Town, stopping a mile-and-a-half short of the village for the night.

Three hours later, Francis and Hale, with a thousand men, many of whom were stragglers and walking wounded, stumbled into Hubbardton. Instead of following after St. Clair, Warner and Francis decided they would stay where they were for the night. Hale’s unit and the stragglers encamped along Sucker Brook, which crossed the Great Road, northwest of where Warner’s men bivouacked at Selleck house on the high ground. Francis’s men took cover in the woods north and right of Warner.

Miles behind the Rebels, Fraser and his men rested along a stream. They had been all day without food, but now butchered two bulls they found in the woods. While they were eating, General Riedesel rode into camp with some jägers, announcing that his corps, which was trudging along somewhere to the rear, had been ordered by Burgoyne to support Fraser. After a short conference, the two officers decided Fraser would push on for another three miles, while the played-out Germans rested for the night. The next morning, at 3 am, Fraser would move out to engage the enemy, and Riedesel would move out at the same time to aid him.

Fraser Decides to Engage the Rebels

Gunfire broke the silence at 5 am on July 7, as two American pickets fired on Loyalist and Indian scouts reconnoitering ahead of the main body of Fraser’s force. For two hours, the Advanced Corps had been on the road, but now they halted on the western slope of Sargent Hill. The Rebel camp was near and Fraser, a veteran of wilderness fighting in the French and Indian War, had no intention of marching into an ambush. An hour later, his Loyalist and Indian scouts reported there was a large number of Rebels over the hill.

Deciding he had to act now instead of waiting for the slow-marching German Brunswickers, Fraser moved over the hill. Major Robert Grant, leading two companies of the 24th Regiment, would slam into the Rebels, while Major Lindsay, the Earl of Balcarres, with 10 companies of the light infantry, would move along Grant’s left flank. Ten companies of the grenadiers would be held in reserve.

Despite the gunfire and reports from their pickets, the Americans seemed oblivious to the British presence. Warner’s and Francis’s men were formed into a column along the road that led south to Castle Town. Most of the 2nd New Hampshire was forming up for the march, while Captain Carr’s company of the 2nd New Hampshire and stragglers leisurely cooked their breakfast along Sucker Brook. Suddenly someone shouted, “The enemy are upon us!”

The British Regulars had just finished deploying in line and were struggling to make their way through the thick underbrush. Major Grant climbed up on a stump to get a better look at the Rebel position when he was instantly killed by a musket ball. Another Rebel volley brought down 21 Redcoats. But the disciplined Regulars charged, overrunning Carr’s company and stragglers, scattering them in the woods.

Warner and Francis immediately ordered their men to form on the crest of Monument Hill behind a stone wall. The 2nd New Hampshire took up position on the right flank of the eight-hundred-yard American line. The Rebels repulsed a British charge and then threatened their left flank.

Fraser was now in trouble. Outnumbered and with the Americans holding the high ground, Fraser brought up his reserves and attempted a risky move. Major John Acland, with a detachment of grenadiers and light infantry, swung around the Rebel’s left flank and, clinging to branches and bushes, climbed over Zion Hill. They now commanded the Castle Town road. The Rebel left flank, thus exposed, was forced to fall back east of the road to Castle Town, behind a log fence.

Meanwhile fighting intensified, as the Americans attempted to turn the British left flank. The situation was quickly becoming serious for Fraser, who had no more reserves, when help arrived. Riedesel, with his jägersand grenadiers, had moved ahead of the rest of his corps and saved the day. The Americans held for a while under the renewed British-German attack, but when Francis was killed the Rebels took to the woods running for their lives. The bloody little battle had raged for 45 minutes inflicting about two hundred casualties for the British and roughly 390 for the Americans, including those captured.

Long’s Forces are Caught Off Guard

While Fraser pursued St. Clair, Long and his escaping flotilla leisurely made their way to Skenesborough. There was no hurry, for they were confident the boom that stretched across the narrow waterways between Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence would halt the British for a considerable time. It was a dangerous delusion.

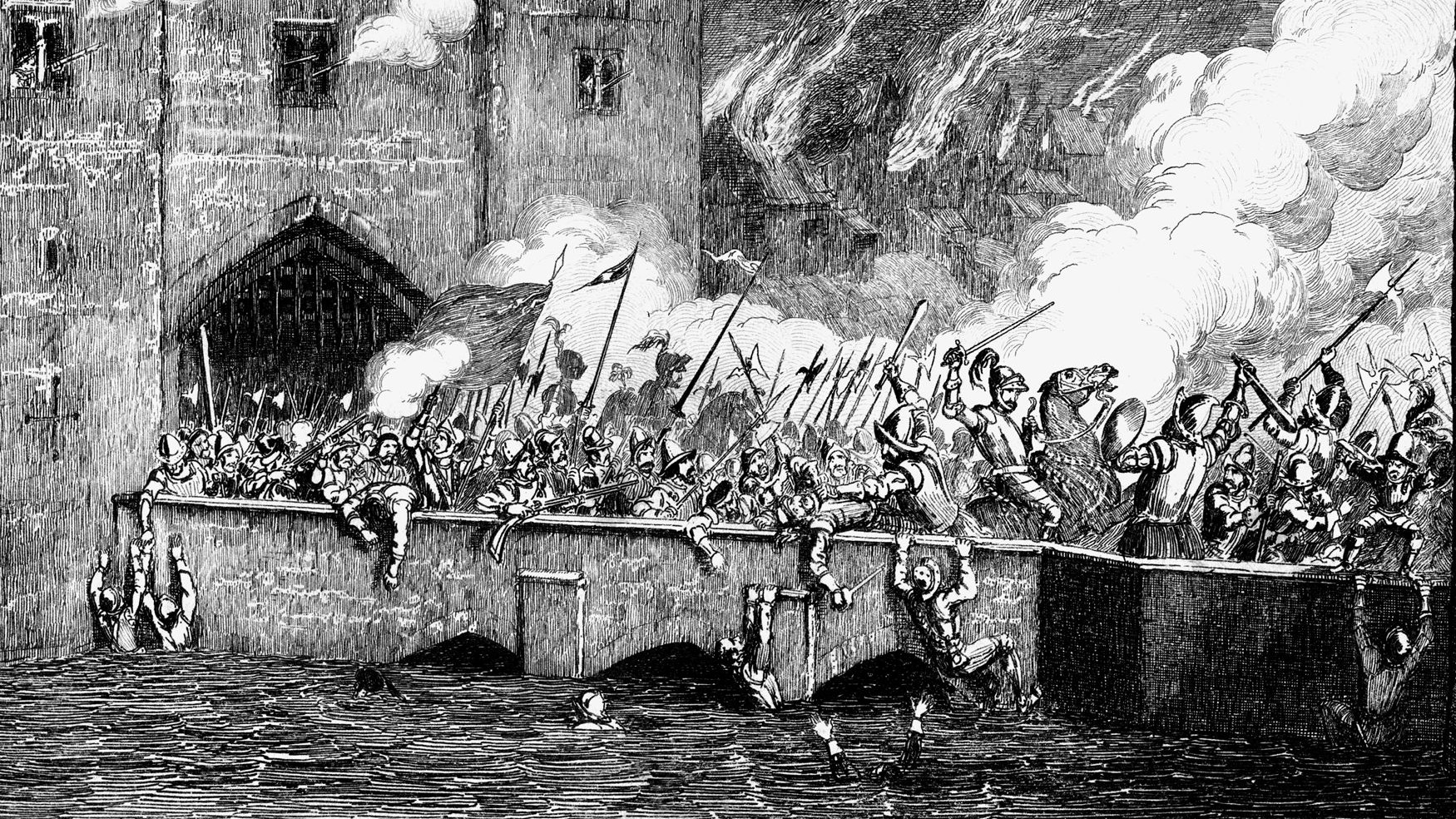

A few well-aimed shots from British gunboats smashed the boom, chain and bridge and within half an hour Burgoyne and his armada were in pursuit. By 3 pm on July 6, the British were within three miles of Skenesborough. Here three regiments, the 9th, 20th and 21st, were landed with orders to get across Wood Creek, a shallow watercourse that led to Fort Anne, and a road that led to the fort as well.

The Rebels were caught totally off guard when Burgoyne’s gunboats and ships opened up on Skenesborough. Three Rebel craft were destroyed, while two more surrendered. The provisions and military supplies laboriously hauled from Ticonderoga either went up in flames or were captured. After sending the wounded and camp followers up Wood Creek in bateaux and setting the blockhouse on fire, which soon spread to envelop surrounding buildings and trees, Long and his men retreated south. Lucky for them the Redcoats sent to block this avenue of retreat were delayed because of the thick forest.

The following day, July 7, while British troops portaged 50 bateaux onto Wood Creek, Lt. Col. John Hill followed after the Rebels with the 9th Regiment. After making 10 miles on a rugged road, Hill encamped for the night a mile from Fort Anne. A deserter the next morning informed Hill that the Rebels had a thousand men at the fort. Hill, who had only 190 men, sent for help.

The Rebel deserter turned out to be a spy, and after sizing up Hill’s force, slipped back to Fort Anne. Long, who had received reinforcements, quickly moved out and attacked Hill. In a wild two-hour firefight, the Redcoats, low on ammunition, prepared to make their last stand on a steep slope. Then, suddenly, an Indian war cry pierced the air over the roar of gunfire. The Rebels retreated, thinking British reinforcements had arrived. The “reinforcements” were in fact one British officer, who was leading a party of native warriors to relieve Hill. The officer had run on ahead of the Indians, who “either stood still or advanced very slow” when they heard battle raging ahead, and did his best imitation of a war cry. At Fort Anne, the Rebels torched the fort and retreated 16 miles to Fort Edward. There they would be joined by the rest of the army and St. Clair, who was forced to change his plan when he heard of the capture of Skenesborough.

Burgoyne Gets Bogged Down

For “Gentleman Johnny,” as Burgoyne was nicknamed by his men for his fair treatment of them, the campaign had reached its high point. With his forces at Skenesborough, he could continue south in one of two ways. He could return to Fort Ticonderoga and head by water over Lake George, then march to Fort George and thence to the Hudson River just above Fort Edward. This was the route he had recommended when he planned the campaign in London, but now he changed his mind. He did not like the idea of falling back—it would hurt the morale of the men. The day before the army set off for Fort Ticonderoga, he announced, “This Army must not Retreat.” Thus he would instead march to Fort Edward on the 16-mile path that was plagued with creeks and swamps. His gunboats, heavy baggage and 33 guns, however, would travel by Lake George.

For the next two weeks, Burgoyne remained at Skenesborough. What had been a rapid advance since leaving St. John, Quebec, in June was now bogged down. The farther south the British Army advanced, the farther its supply line was stretched. To keep provisions coming from Canada took men, bateaux and horses, the latter of which Burgoyne was short on. The situation was quickly becoming a quartermaster’s nightmare that would only get worse.

A thousand Rebel troops were also doing their best to make life miserable for the British. Trading their muskets for axes, they choked the road to Fort Anne and Fort Edward with fallen trees, destroyed bridges and swamps created by digging ditches from bogs. They plugged Wood Creek with boulders and ordered the inhabitants to drive their cattle out of the reach of the Redcoats.

When Canadian axeman, battling mosquitoes and the sultry heat, finally cleared the way, Burgoyne got his army moving from Skenesborough on July 24, reaching Fort Anne two days later. The journey was unbelievably rugged. Packhorses and wagons could not travel with loads or else they would get stuck in the mud.

Problems with Indians

Before leaving Skenesborough, Burgoyne’s native force was reinforced by five hundred western Indians on July 17. Shortly afterward Burgoyne had a diplomatic conference with them, reminding those present that it was acceptable to scalp enemy killed in battle, but prisoners, women and children must be left alone. Once they recovered from the feast that was held afterward, the warriors set out on business.

War parties spread out taking the war to the Rebel soldiers and, despite Burgoyne’s orders to the contrary, the civilian population. Warriors began returning to British camp with prisoners and scalps. At Fort Anne two warriors arrived with a blonde scalp. A Loyalist officer immediately recognized it to be that of his fiancée, Jane McCrea. The Indians had been sent out to bring her in safely and for some reason had killed her instead. Burgoyne demanded the culprits be executed, but his Indian agents warned that to do so would cause the natives to desert. Instead Burgoyne insisted British officers accompany every raiding party heading out.

When the British finally limped into Fort Edward—the Rebels had abandoned it for farther retreat south—glad to be out of the wilderness, Burgoyne had another conference with his Indian allies. He reminded them about killing innocent people. The Indians agreed. The next day, laden with plunder, the western Indians packed up and headed home.

This was not the only piece of bad news to confront Burgoyne at Fort Edward. Word reached him from Howe that he would not be joining him at Albany. Instead Howe was heading for Pennsylvania. The campaign to sever New England was quickly coming apart. The first major setback was only days away.

Baum’s Disastrous Foray

The German dragoons needed mounts and it was reported there were lots of horses in the Connecticut Valley. On August 4, Burgoyne ordered Lt. Col. Friedrich Baum to take 1,200 men, Germans, Loyalists and Indians, and march into Vermont “to try the affections of the people, to disconcert the councils of the enemy, to mount Riedesel’s dragoons, to complete Peter’s Corps and to obtain large supplies of cattle, horses and carriages.” Baum may not have been the best choice to lead such a mission, because he had no experience in fighting in North America, and he could not speak English. Nevertheless on August 9, Baum’s force marched from Fort Edward headed for Manchester, Vermont. Not long afterward Burgoyne countermanded the order and directed Baum to head to Bennington, where Captain Justus Sherwood of the Queen’s Loyal Rangers and a handful of his men scouted the area earlier and reported there was a huge stockpile of supplies guarded by only four hundred men.

While the Germans advanced at a snail’s pace toward Bennington, the Rebels mobilized to stop them. Under the command of Brig. Gen. John Stark, fifteen hundred men took up their muskets and fowling pieces and headed for Bennington, spoiling for a fight. They wouldn’t have to wait long.

From prisoners Sherwood and his men captured, Baum learned of the increase of Rebels at Bennington. Despite this he pushed on and after driving away Rebel resistance, captured a grist mill nine miles from Bennington. Baum then dispatched two letters to Burgoyne. One informed the commander of capturing the mill and the supplies there and of his intentions to attack the large Rebel force the next day, August 15. His second letter, sent after a skirmish with the Americans, asked Burgoyne for reinforcements.

Heavy rains the following day delayed any chance for a battle. Baum, however, did not remain idle. By this time he was becoming concerned over the growing Rebel forces and decided to dig in and wait for reinforcements. The mainly German/Loyalist force was spread out: 170 dragoons and 20 of Fraser’s marksmen, a small party of Indians and a 3-pounder gun took up position in a log redoubt on a steep hill; a detachment of Germans, another gun and the rest of the marksmen guarded the bridge across the Walloomsac River; a Loyalist force took up position 250 yards south of the bridge behind log breastworks; another force of Germans and Loyalists was posted at the bottom of the hill to guard the road and bridge from the rear; and a small detachment of jägerswas positioned southeast of the hill.

Stark, who had received reinforcements on the morning of the 16th, prepared to encircle Baum and attack him on all sides. At noon the American troops moved out to get in position. Two hundred New Hampshire men under Colonel Moses Nichols moved around Baum’s left, while Colonel Samuel Herrick and three hundred rangers and militia moved on the German right. Colonels Thomas Stickney and David Hobart were to take out the Loyalist position south of the bridge. A hundred troops were to draw the attention of Baum’s position, while Stark, with the rest of the soldiers, waited for the main frontal attack.

At 3 pm, with the American troops in position, Nichols’ men fired, followed by Herrick’s men. This was the signal to begin the attack. “We’ll beat them before night, or Molly Stark will be a widow,” Stark cried as the frontal assault began.

The Loyalist position south of the bridge was overrun, forcing its defenders to retreat across the river. The attack on Baum’s position was a bloody fight that lasted two hours. Then as Baum’s men’s ammunition was running low, the wagon containing the rest of the powder and lead caught fire and exploded. Baum, with only his dragoons remaining, the rest either dead or deserted, attempted to cut through the Rebels with their broadswords. The breakout failed as the Americans quickly encircled them. They surrendered after Baum was mortally wounded. But still the day’s fighting was not over.

Breymann’s Turn to be Routed

Lumbering at half a mile an hour came the 642 German reinforcements sent by Burgoyne. Under the command of Lt. Col. Heinrich Breymann, the Germans reached Sancoick’s Mill, six miles from the battlefield, at 4:30 pm. From then on the Germans pushed their way through Rebel skirmishers sent by Stark to delay them.

The Rebels, after defeating Baum, were in no condition for another fight. They were scattered around the battlefield plundering the enemy. Then Breymann appeared. Stark managed to rally enough militiamen to oppose the new threat, but if he was to defeat the Germans, he desperately needed more. Fortunately reinforcements from Manchester arrived just in time. Both sides poured a heavy fire into each other. Running low on ammunition and with more Rebels joining the fight, the Germans retreated. The Rebels pursued, causing the German retreat to turn into a rout. Some Germans attempted to surrender, their drummers beating a parley. The Rebels, not knowing the meaning of the signal, shot them down.

Breymann and less than two-thirds of the force remaining were left to retreat into the darkness. “Had the day lasted any longer, we should have taken the whole body of them,” Stark would later say. In all, it had been a bloody day for the Germans and Loyalists. Over nine hundred of them were captured, killed or wounded, while the Americans suffered about 70 casualties.

News of the disaster was brought back to Burgoyne by the escaping Loyalists and Indians. The German prisoners were being treated well enough, they informed the commander, but the Loyalist prisoners were being dealt with cruelly. Any hopes of obtaining fresh horses and provisions were dashed. One-seventh of is army had been lost, and, to make matters worse, the majority of the Indians after the defeat decided they had had enough and left. Despite these setbacks, Burgoyne, with 25 days of supplies, decided to fight his way to Albany and wait cooperation from New York.

Gates Takes Command of a Growing Rebel Force

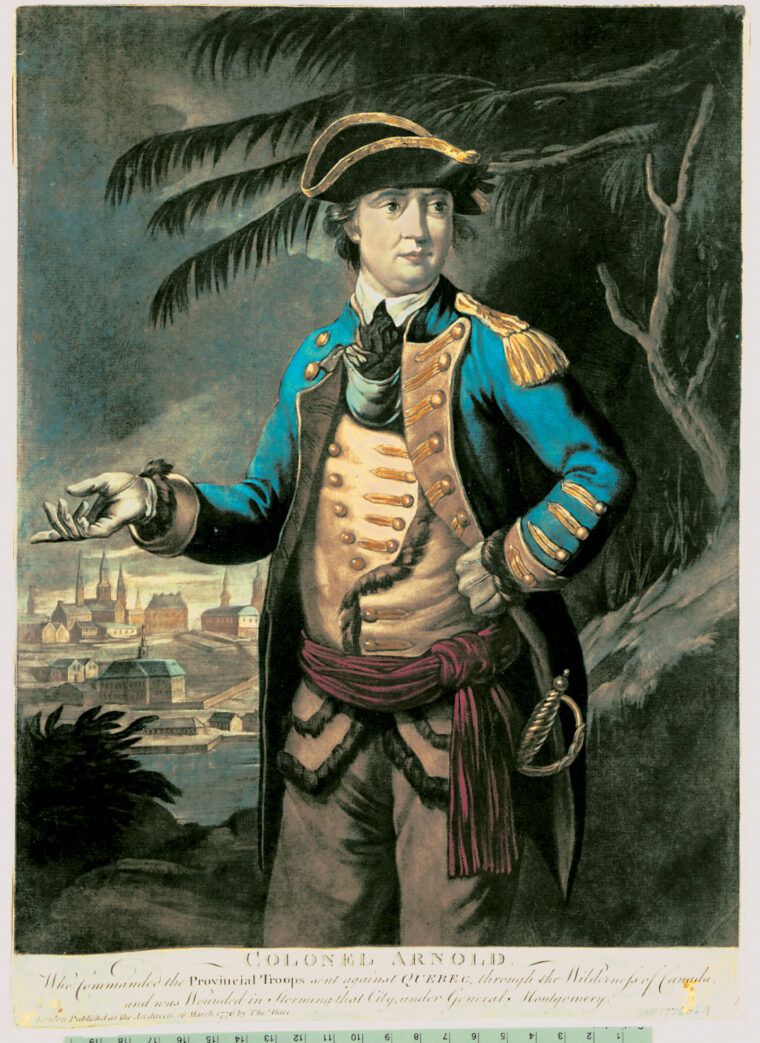

On August 19, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, an ex-British officer, arrived in the American camp where the Mohawk River flows into the Hudson north of Albany and took over command from Maj. Gen. Schuyler. The 4,500-man army Gates found was plagued with sickness and low morale. It was, however, growing daily. Twelve hundred men arrived under Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold. George Washington dispatched a corps of riflemen, under the command of the big, raw-boned frontiersman Colonel Daniel Morgan, to join Gates. Militia companies began pouring into the camp. By early September, the American army numbered seven thousand men.

Gates and his army moved north, arriving at Stillwater on September 9. They began digging trenches but later decided this was not a defendable position. They then moved three miles north to Bemis Heights. This wooded plateau, besides offering visibility in every direction, commanded the only road to Albany, which ran along the west side of the Hudson River. It was here the Americans built their fortifications and awaited the British.

It was not until September 13 that the British set out for Albany. Burgoyne had decided he would cross the Hudson and travel down the west side of the river, knowing he would have to fight his way through the Rebels. The east side would offer less Rebel resistance, but the army would have to cross the Hudson at Albany, where it was wider and deeper and would offer greater advantage to Rebel troops who would be waiting there. After the Germans crossed the temporary bridge across the Hudson two days after the British, the bridge was dismantled, severing communication with Canada.

Burgoyne was now really on his own. Earlier he received intelligence that St. Leger’s diversionary force moving up the Mohawk Valley had been stopped at Fort Stanwix and been forced to give up the campaign.

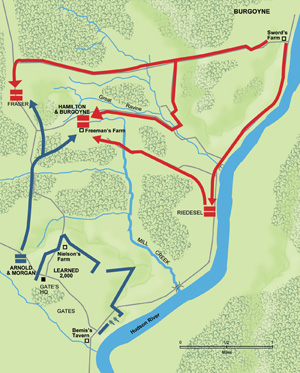

The Battle of Freeman’s Farm

A heavy fog blinded the countryside on the early morning of September 19. It was 10 o’clock before the sun burned off enough fog for the army to get moving. The bellowing of cannon shots signaled the start. Burgoyne’s army advanced as usual in three divisions: Fraser’s Advanced Corps on the right, the British in the center, and the Germans on the left. Scouts had reported a weakness in the Rebel position at Bemis Heights. High ground two miles west of Gates’ position was undefended. Fraser was ordered to capture this ridge, forcing the Rebel left flank to be turned, driving the Americans to the river where they would be surrounded by the rest of the British and Germans. The plan was risky, because several of Burgoyne’s divisions would be separated from each other should the Americans attack.

American scouts reported that the British were on the move, yet Gates did nothing. Arnold, on the other hand, was anxious to move out and engage the enemy before they brought up their guns and bombarded the American fortifications. Reluctantly, Gates allowed Morgan’s Rifle Corps and Major Henry Dearborn’s Light Infantry to harass the enemy moving against their left flank.

Forming his riflemen in two thin lines, Morgan and his men moved through the woods, taking position along a rail fence on the southern edge of Freeman’s Farm. British skirmishers from the center division were searching around the farm buildings when the crack of rifle fire dropped every officer and many of the men. The skirmishers fled, with Morgan’s riflemen hot on their tail.

Musket fire from light infantrymen under Captain Fraser smashed into the charging riflemen’s left flank, sending them scurrying back into the forest. Colonel Morgan, tears streaming down his cheeks thinking his corps was ruined, let out turkey gobbles in an attempt to regroup his men. They rallied and the fight was on.

New Hampshire Continentals from Arnold’s division appeared on the scene and fell into the left of Morgan and Dearborn. British artillerymen quickly rolled their guns into position along the northern edge of the 20-acre clearing. Red-coated Regulars from the 21st, 62nd and 20th hurried into position along the northern edge as well. As more American reinforcements arrived throughout the day they witnessed furious fighting.

The clearing became piled with bodies as fighting see-sawed back and forth across the blood-soaked battlefield. Arnold, noticing how the 21st was separated from Fraser’s Advanced Corps, attempted to cut the British in two. His plan failed and the battle turned into a slug fest as both sides struggled for the British guns. Riflemen took their toll on British artillerymen, killing 36 of the 48.

The 62nd Regiment, taking heavy casualties throughout the fight, at one point would have been routed had not the 20th come to their rescue. Burgoyne, who was in the thick of the fighting, knew the situation was desperate. The center division was barely holding on.

Arnold was aware of the weakening British position and requested more reinforcements to break the enemy. Gates, safe at his headquarters, refused, deeming “it not prudent to weaken” his position on Bemis Heights. He did eventually send General Learned’s Brigade late in the day, which headed in the wrong direction and struck Fraser’s men on the right wing, only to be repulsed.

Riedesel, moving slowly along the river, heard the escalating battle up ahead. He dispatched an officer to find out what was happening and to get Burgoyne’s instructions. Burgoyne’s instructions were that the artillery and baggage were to be protected, while Riedesel was to move with as many troops as possible to aid the British center. Taking his own regiment and two companies from von Rhetz’s brigade, plus two 6-pounders, Riedesel headed to the rescue.

They arrived just in time, with the British on the point of collapse. With their drums beating and the troops shouting, the Germans slammed into the Rebel right flank. Musketry and grapeshot ended the battle. The Rebels retreated back to their camp on Bemics Heights in the growing darkness. The British, too tired to pursue, bivouacked where they were.

It had been a bloody day, later known as the Battle of Freeman’s Farm. The British suffered almost six hundred killed, wounded or captured. The 62nd received the worst drubbing. They started the day with 350 men but by nightfall had been reduced to 60. The Americans had a little over three hundred casualties. The British won the battle, but their losses were irreplaceable, while the American forces would continue to grow, as the days ahead would show.

Burgoyne’s Fateful Decision to Wait for Clinton

The following day, Burgoyne was tempted to attack the Rebels. He might have been successful, too, for the American troops were exhausted and low on ammunition. But the three British regiments that slugged it out with the Rebels the day before were in too poor a condition to engage in another battle. Burgoyne decided he would give his troops a day of rest and attack the following day.

The attack never materialized. A message arrived from General Clinton, the British commander of troops in New York, written on September 12, informing Burgoyne that Clinton planned to move on Fort Montgomery along the Hudson River in 10 days. Such a move by Clinton might draw troops from Gates and pull him from the fire. Burgoyne made the fateful decision to build fortifications where he was and wait for Clinton.

For the next couple of weeks, both armies remained where they were. American skirmishers harassed British pickets and foraging parties, keeping them on constant alarm. Soldiers and officers slept in their clothes, ready for instant action.

On October 4, Burgoyne called a council of war with his top officers. He was running low on food, desertion was high, the troops were on constant alert, and no word had arrived from Clinton—something had to be done to alleviate the growing problems. Burgoyne proposed to leave eight hundred men to defend the army’s boats and supplies by the river and attack Gates’ left flank with the rest of the troops.

Others thought this was too risky. No one knew for sure the layout of the Rebel position and by the time the troops made the slow march around the American left, their supplies would be open to attack. The floating bridge earlier constructed across the Hudson would fall into American hands and the army would be forced to surrender. Riedesel thought a retreat north to a camp of mid-September where the Batten Kill flowed into the Hudson would be a better idea. Communication with Lake George could be reopened and they could wait there for Clinton’s arrival.

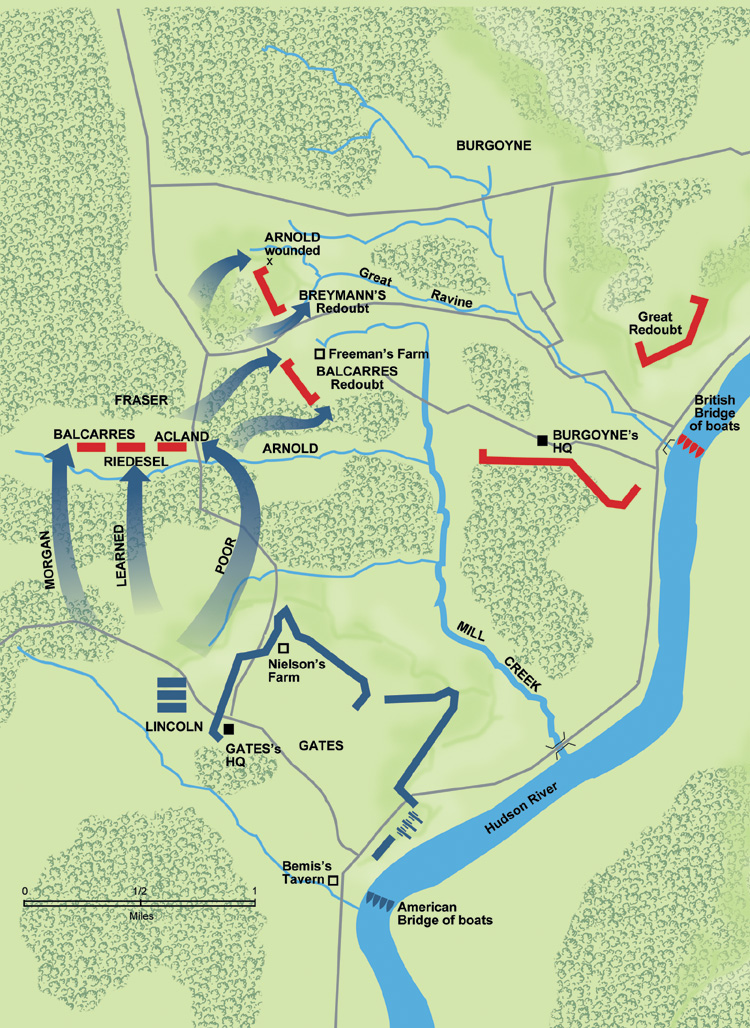

No retreat, argued Burgoyne. At least not yet. Instead he proposed to send a “reconnaissance in force” of 1,500 men to check out the Rebel position and determine its strength. If the Rebels could be attacked, he would do so the next day. If not, they would retreat to Batten Kill.

Three days later, the reconnaissance in force set out in three columns. The British light infantry took the right, while a detachment of Brunswickers and jägers took the center, and finally British grenadiers covered the left flank. Making a long route to the west were Captain Fraser and his men, plus some Indians, Loyalists and Canadians who were attempting to divert the Rebels.

Three quarters of a mile southwest of Freeman’s Farm, the troops held up in a field while foragers cut wheat. Burgoyne, Riedesel, and Philips climbed up on the roof of a log cabin and attempted to spot the enemy with their telescopes. They saw nothing but trees. Concealed from them, an American officer a thousand yards away observed everything. Rebel pickets earlier had reported British troops on the move and the officer was sent to investigate. He got an eyeful.

After 15 minutes of observing the Redcoats, the Rebel officer was back reporting what he had seen to Gates. “Well then, order Morgan to begin the game,” ordered Gates. Morgan’s Corps slipped out of camp, quietly circling their way around the British right, with orders to strike. At the same time Brig. Gen. Enock Poor’s Brigade would hit the British left. Learned’s Brigade, meanwhile, would be held in reserve, ready to attack the British center.

Around 3 pm Poor’s Brigade was spotted by John Acland’s Grenadiers positioned on the high ground. They opened up on the Rebels with their artillery, which proved ineffective because the thick woods absorbed many of the cannonballs. The Rebels endured musketry and grapeshot as they advanced on the British. They loosened a volley, then exploded on the Redcoats, overrunning their guns and driving the grenadiers back. Acland went down, shot in both legs, and was captured.

At the same time, Morgan’s Corps “poured down like a torrent” on the British right. The light infantry, under Alexander Balcarres, attempted to change front, when Dearborn’s Light Infantry (which was supporting Morgan) drove them from the cover of a rail fence. Balcarres attempted to rally his men behind another rail fence, when Morgan and Dearborn routed them. The light infantry headed for the safety of their own lines.

The Germans, in the center, were now without support. Learned’s Brigade, commanded by Benedict Arnold, headed straight for them. During the lull after the battle of Freeman’s Farm, Arnold and Gates had been feuding. Gates had failed to mention Arnold’s name in his report of the battle, much to the dismay of Arnold. Relations continued to get worse, finally culminating in a heated argument in which Arnold was relieved of command. Arnold stayed in camp as a hanger-on, waiting for the coming battle. Now with a major engagement under way, Arnold galloped to the battlefield and, although he had no authority to do it, urged Learned’s Brigade to follow him. Apparently Learned did not mind. The Rebels smashed into the Germans and were repulsed. With their right flank now open, with the collapse of the light infantry, the stubborn Brunswickers soon were ordered to fall back when they saw they were almost surrounded.

Astride his horse, Brig. Gen. Simon Fraser attempted to rally his regiment, the 24th and the light infantry into a second line. “That officer upon a grey horse is of himself a host, and must be disposed of …,” commented Arnold to Morgan. Morgan ordered his riflemen to take him out. Tim Murphy climbed a tree and after two near hits, gut-shot Fraser on the third. Fraser was a brave and energetic officer and he was a great loss. The battered “reconnaissance in force” sought the shelter of its breastworks.

But the battle was far from over. Arnold, with part of two brigades, attempted to break through the part of the breastworks held by Balcarres’ light infantry. Musket balls and grapeshot drove the Rebels back. The best they could do was to blast away at the British from the cover of trees.

Meanwhile, Learned’s Brigade was moving on the British right. After Arnold’s attack failed against the light infantry, he spotted Learned’s movement and galloped through enemy fire to be in on the attack. The Rebels quickly overran two stockaded cabins, situated between two German redoubts. The Americans then pushed on and struck the open rear of the German redoubt commanded by Breymann. It fell, but not before Breymann was killed and Arnold was wounded in the leg.

With the loss of this redoubt on Burgoyne’s right, his position was open to attack from the right and rear. The growing darkness ended the fight for the day, and just as well for the British and Germans—they had suffered almost nine hundred killed, wounded and captured. The Rebels suffered about 150 casualties.

Under the cover of darkness, bone-tired soldiers filed out of the British fortifications at Freeman’s Farm and headed to the redoubts closer to the river protecting the artillery, supplies, hospital and bateaux. Despite the fact that Gates’ army numbered 12,000 men, he did not press an attack on the British the following day.

The British Retreat

Nevertheless, Burgoyne knew he was in calamitous trouble. In a last-ditch effort to save his army, Burgoyne ordered a retreat for Ticonderoga, 60 miles to the north. On the night of the 8th the troops plodded north, while supply wagons and the artillery train creaked and rolled along with them. In the river, the bateaux rowed alongside the army.

It was an agonizingly slow retreat. Heavy rains turned the roads into a quagmire on the first day, causing the wagons to get stuck. Some of the baggage was abandoned. A large number of the bateaux fell into American hands. Finally, in the late evening of the 9th, the weary army stumbled up the heights of Saratoga and stopped. There were already fortifications here, built by Burgoyne almost a month earlier, then further strengthened.

American troops began to encircle Burgoyne’s position, attempting to cut off any chance of retreat. In their haste, the Rebels almost attacked blindly into Burgoyne’s camp on the 11th, thinking it was only the rear guard. Earlier, Burgoyne had sent a force north to Fort Edward in an attempt to build a bridge across the Hudson River. It was this force that Gates thought was the main British army retreating. Lucky for the Rebels, this mistaken belief was discovered before an attack commenced into the waiting guns of the British, an event that would almost certainly have been an American defeat.

By the 12th, an escape route to the north was still open for the British. Burgoyne called a council with his principal officers to determine what should be done. After weighing their options it was decided they would retreat without the baggage and artillery. But it was never to happen. For some reason, Burgoyne postponed the retreat, thus allowing General Stark and his New Hampshire militia time to seal the northern escape route. The game was just about up.

Surrender

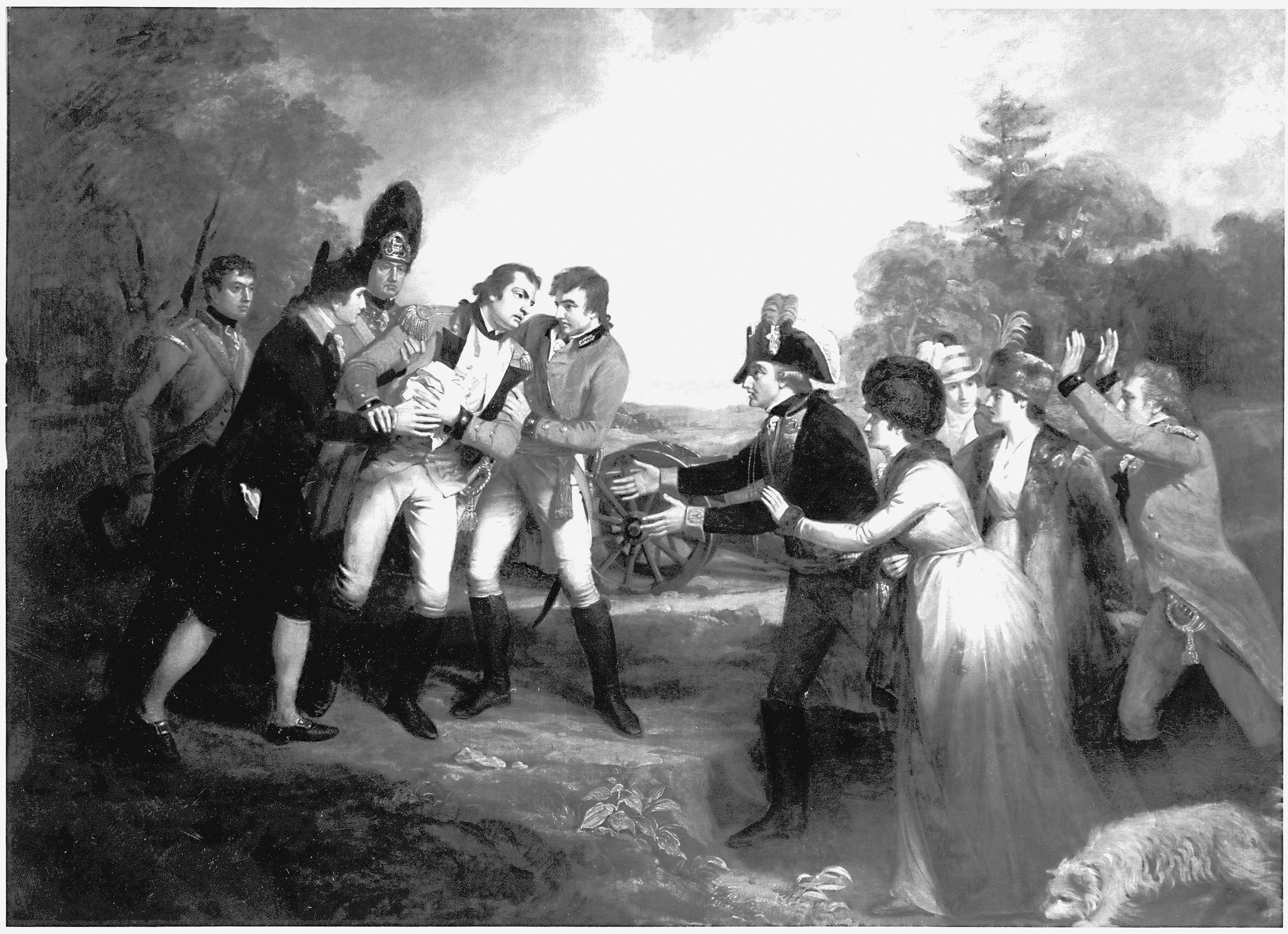

On the morning of the 14th, Burgoyne began talking surrender terms with Gates. There was haggling on the terms and wording of the surrender. It was finally agreed that Burgoyne’s troops would march out and ground their arms; the troops, who were not to be considered prisoners of war, would be allowed to return to England from Boston on British ships agreeing not to fight in North America during the present war (this term would not be honored by Congress); the troops would be fed and quartered at American expense, officers would be allowed to keep their carriages and horses; the Canadians would be allowed to return to Canada; and the agreement must be called a convention rather than a capitulation.

A Loyalist made his way into the British camp on the 15th with news that soldiers had been moving from Gates’ camp. Clinton was reported to be in Albany. Believing that Clinton would rescue him, Burgoyne wanted to scrap the surrender terms and hold until help came. His officers argued against the idea, pointing out that the army was worn out, low on food and if the treaty was not signed the Loyalists, Canadians and civilians’ lives would be in jeopardy. Burgoyne sent a letter to Gates on the morning of the 16th mentioning that he heard a large part of Gates’ force had been detached, and wanted two of his officers to inspect the American army to determine their strength. Gates refused, telling Burgoyne it was time “to ratify or dissolve the treaty.” Burgoyne agreed. It was just as well, because Clinton was not on his way. He had moved up to the Highlands of Hudson Valley 40 miles above New York and taken Fort Montgomery and Fort Clinton. But that was all—at best he was hoping to create a diversion, but had no intention of fighting all the way through to Albany.

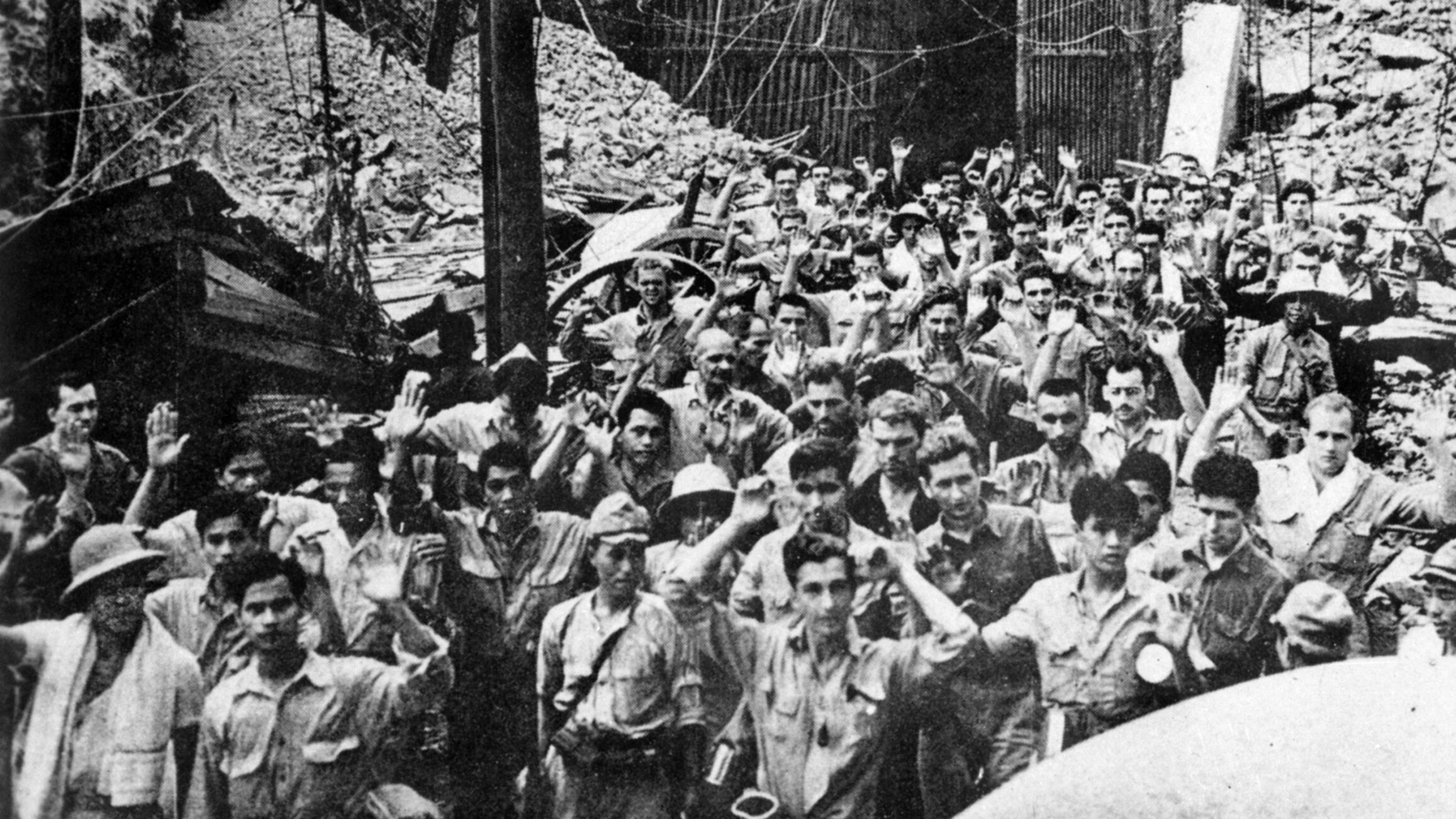

With flags flapping in the wind, drums beating and fifes playing, the British, German and remaining Loyalist troop (Burgoyne, before he signed the treaty, had urged his Loyalist troops to slip through the American lines and escape to Canada, for he feared for their safety once in Rebel hands) marched to an appointed place by the river, piled their arms and then marched through the American camp where the Rebel troops were lined in two rows. The American soldiers showed no disrespect for their enemies. Burgoyne, in his best uniform, surrendered his sword to Gates who handed it back to him. The great campaign was over.

It was a momentous victory for the Americans. They had captured an army of five thousand men, along with such military supplies as their cannon and muskets.

But this was the lesser part of the American victory and the British woe. The greater part was the impact of the victory on the French, who had been secretly aiding the Rebels. On February 6, 1778 France formed a treaty with the United States making the powerful European nation—and its tremendous fleet—an ally of the Americans. The alliance proved to be the cornerstone in the ultimate American victory in its struggle to free itself of Great Britain. Saratoga was the turning point of the Revolution.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments