By Phil Zimmer

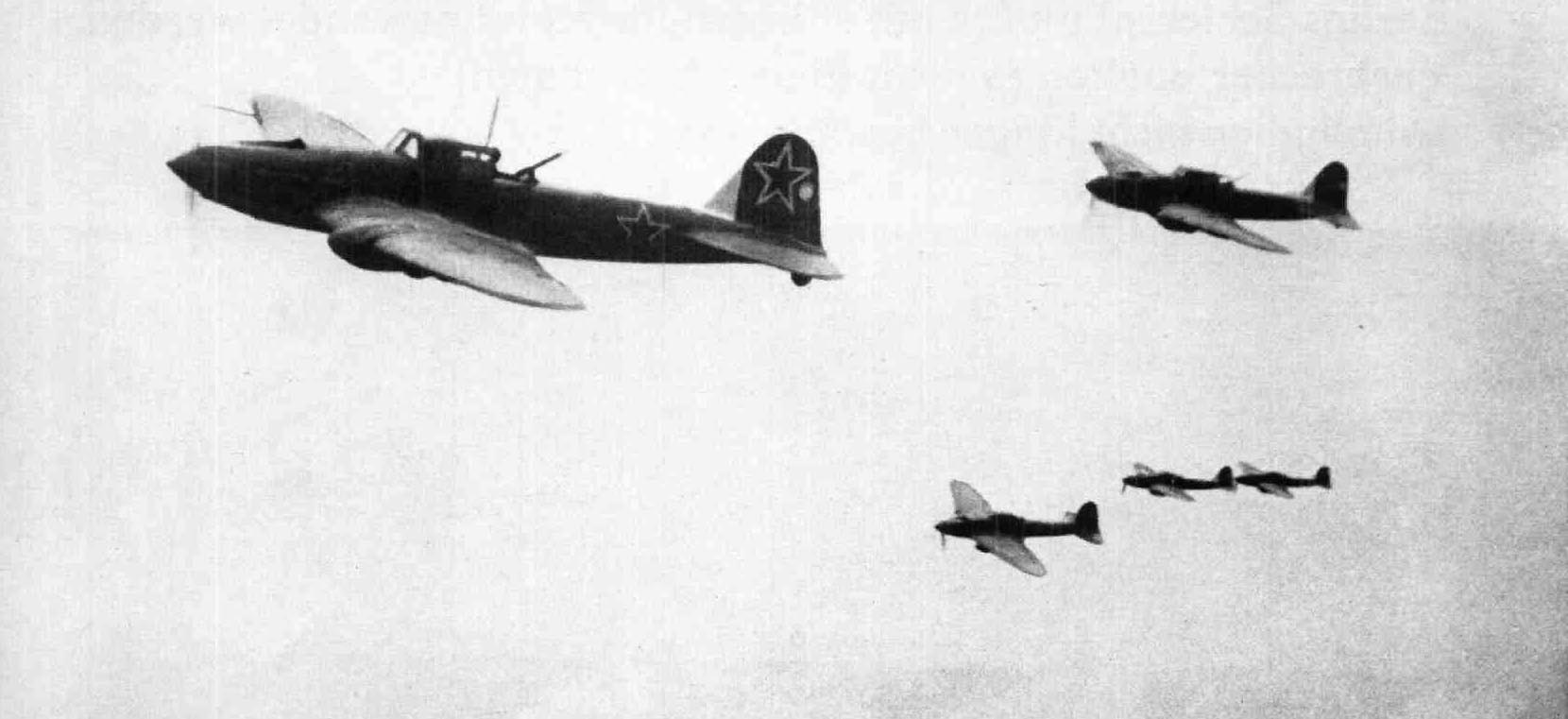

Vasily Emelianenko led an Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmovik, or “Storm Bird,” flight in late June 1942 against a German-held airfield near Artemovsk in eastern Ukraine, flying low up a deep ravine to avoid detection.

The Il-2 planes banked slightly to rise above the hill to their front, and the ground gave way as they spotted two rows of German bombers lined up neatly on the airfield ahead. Emelianenko had lowered the nose of his plane for the attack when he heard a deafening sound and the craft jolted suddenly as a large hole burst open in his right wing. He worked swiftly, straightening the plane and firing a salvo of rockets into the parked enemy aircraft. Emelianenko’s machine guns then erupted, and the bombers caught fire. His wingmen dropped their granular phosphorous, which spread the flames that roared even higher into the sky.

Emelianenko worked desperately to pull his plane above the wall of tall pines located beyond the airfield, but the plane was hit in the engine. The oil pressure plummeted toward zero, and the water temperature soared. The experienced pilot knew he had five minutes at best before the engine seized as he frantically maneuvered toward the safety of the Soviet lines.

The pilot skimmed the terrain, and every spin of the propeller pulled him ever closer to the safety of the Soviet lines. The engine finally seized up, and Emelianenko released the robust landing gear and came roaring down on the rocky soil at more than 60 miles per hour. He was miraculously still alert as the dust settled around him. He looked about to get his bearings as a burst of machine-gun fire struck the plane’s heavy armor plating. There was another burst, and when that ended Emelianenko jumped from the cockpit and fell flat on the ground as German machine pistols opened up.

The enemy soldiers seemed almost to be toying with him, firing anytime he moved yet not advancing or showing themselves. It took the pilot more than two harrowing hours to crawl some 200 yards from the plane and to the safety of a Soviet comrade who had carefully edged forward to rescue the downed veteran.

That would not be Emelianenko’s last brush with death flying a famed “Ilyusha,” the feminine nickname the Soviet pilots affectionately gave their stout attack aircraft. Before the war was over he had flown 92 sorties on the Eastern Front, was proclaimed a Hero of the Soviet Union, and had been shot down three times with the sturdy, armor hardened plane saving his life in each brush with death.

The Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmovik proved deadly throughout the war. For example, as the Battle of Stalingrad was nearing its fateful conclusion, two feared Soviet Sturmovik ground attack planes appeared over the crucial German-held train station at Malorossiyskaya to the south in the Tikhoretsk region.

The Germans scrambled that January 26, 1943, but it was too late. A series of deafening explosions rocked the four trains that sat exposed on the tracks, and a large black plume rose high into the sky as the station itself was obstructed from view in the wake of the destructive attack.

All four trains were destroyed by just the two Soviet “Storm Birds,” with a substantial loss of German personnel, fuel, tanks, and ammunition vital to the continued war effort. The tracks themselves were so badly damaged that they could not be readily repaired, and many stranded trains were captured by the advancing Red Army.

The Ilyushin Il-2 was built for business and could deal deadly blows to ground-based forces and equipment, even when located in hardened bunkers. By the midway point in World War II, the planes came equipped with two 37mm cannons, two 7.62mm machine guns, one 12.7mm Berezin machine gun for the rear-facing gunner, and up to 1,300 pounds of bombs or a number of deadly RS-82 or RS-132 rockets.

The rockets, especially the RS-132s, were powerful but were not overly accurate. However, they did prove particularly destructive, especially when fired in volleys from several planes. The aircraft also could carry upward of 216 bottles of incendiary liquid, which proved effective against armor and flak batteries as well.

The success of the train station mission and others like it, executed with considerable heroism by the Sturmovik pilots, prompted Soviet Premier Josef Stalin to issue an order calling for the continued attack of trains and convoys to disrupt German preparations for the upcoming Battle of Kursk, the famed tank battle that led to a near continuous German backpedaling toward Berlin over the next 21/2 years in the face of growing Soviet military prowess.

Why the Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmovik Was Known as a “Flying Tank”

The Sturmovik was both respected and loathed by German pilots, infantrymen, and tankers. The Luftwaffe took to calling it the “Flying Tank,” “Concrete Plane,” or even “Iron Gustav” because of its highly effective armor protection, while German tankers and infantrymen referred to it as the “Butcher” or even the “Black Death” because of the destruction left in the wake of an Il-2 attack. The robust plane proved that it could more than hold its own against the vaunted Luftwaffe, especially as Soviet tactics improved and pilots gained experience against German flyers who became younger and the veterans fewer as the bloody “Great Patriotic War” pushed ever westward.

The plane was so detested that it became a fairly common practice on the Eastern Front for frustrated and battle-weary Wehrmacht soldiers to simply open the canopy of a downed Sturmovik and fire point blank into the head of an injured pilot.

The Il-2s themselves also improved over time, moving from somewhat underpowered single-seaters to two-seaters with a more robust powerplant and a machine gunner added behind the pilot to provide better protection against attacks from German fighters, particularly from above and behind.

In many ways the Sturmovik was a forerunner of today’s A-10 “Warthog,” developed by Fairchild Republic for the U.S. Air Force and used for close air support, which is capable of providing punishing damage to hardened ground targets while protecting its pilot with its toughened shell. The A-10 Thunderbolt Hog can spew 30mm high-explosive rounds from a seven-barreled, high-speed cannon protruding from its nose and can carry a deadly array of rockets and other weapons under its wings.

The “Storm Bird” was the right plane developed at the right time by the Soviets. It was designed for survival in the hostile, flak- and fighter-filled skies of the Eastern Front, where the Germans risked so much and suffered more than 70 percent of their causalities during World War II.

The Il-2 had a sturdy undercarriage that enabled often quickly trained pilots to take off and land on comparatively primitive airfields. And it was praised for being easier than bombers to operate in adverse weather conditions. It was also relatively easy and inexpensive to produce, with more than 36,150 of all variants rolled out during the war, making it the most produced combat aircraft of all time.

Evolution of the Sturmovik

Like most aircraft, the Sturmovik evolved from previously designed planes to meet a specific need, in this case close air support. The 1939 Mongolian-Manchurian border conflict with Japan, the Spanish Civil War, and the early Winter War with Finland all demonstrated the need for such an aircraft. Various designs were attempted, most employing Soviet RS-82 rockets for air-to-air attacks and later for air-to-ground attacks as well.

Soviet lack of success in using such bombers as the Tupolev SB in the Spanish Civil War had caused the Red Air Force to shy away from the concept of strategic bombing in favor of fast-moving fighters to first gain air superiority and then to be employed in close air support. The decision to move toward a dedicated armored ground attack aircraft led in 1938 to the development of the TsKB-55, which was later called the Ilyushin after Sergey Ilyushin, the project director.

The plane first flew on October 2, 1939, a month after Germany, then the Soviet Union’s ally, invaded Poland and ignited World War II in Europe. The craft at that trial stage was a two-seater, single-engine monoplane. Vital components, including the engine and the entire crew compartment, were heavily armored, and the plane was equipped with five 7.62mm machine guns, one for defense and four in the wings for offensive fire capability. Armor plating of varying thicknesses was used rather than just a layering of armor over existing structures as was then most often done.

Designer Ilyushin sought solid performance for the aircraft, which necessitated the selection of a more powerful and available liquid-cooled engine over an air-cooled radial option. He believed the armor plating would provide the necessary protection for the potentially vulnerable cooling system. Ilyushin selected the Mikulin AM-35 engine, which provided 1,350 horsepower on takeoff, and gave the go-ahead for the development of even more powerful engines.

Further engine improvements were made along with a modification of the glazing where the rear gunner was initially placed, giving rise to the nickname of “Gorbatiy,” or “hunchback” in Russian. The plane at that stage had two 20mm cannons (later replaced with two 23mm cannons) and machine guns in the wings. Trials continued, and the go-ahead for production was given in early March 1941, some three months before Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22 of that year.

The Soviets came to appreciate the plane that the Germans described as the “Butcher” or “Meat Grinder” or even the “Slaughterer.”

Some of the Ilyushin Il-2s had nearly full metal fuselages, including metal wings, but because of wartime shortages of metal other variations had wooden wings and still others wooden rear fuselages. Those with rear wooden fuselages needed additional reinforcement, with four metal strengthening ribs added in the field to the exterior of the fuselage. Field modifications occasionally included ski-equipped versions and the cutting of a hole behind the canopy for the addition of a rear gunner position, the plane’s second occupant using a commandeered machine gun attached to a swivel mount.

All types of Sturmoviks were exceptionally hardy, and all were well armored. Even when one was shot down or heavily damaged, Soviet forces would retrieve and repair the plane or at least salvage parts for later use. A rather astounding 90 percent of the damaged Ilyushas that were recovered were repaired and sent back into the air, according to Soviet estimates.

Operations in 1941-1942 had shown the need for a rear gunner to provide protection against fighter attacks from above and behind the pilot, especially once the Germans discovered the inherent weakness in the unprotected rear wooden fuselage. The problem was exacerbated by the lack of effective, if any, fighter escort for the close air support planes during this initial period of the war.

By September 1942, the Soviets began modifying the Il-2 on the assembly lines to accommodate a rear gunner. The protective armor plating was extended, a semi-enclosed glass covering was added, and a rather crude strap seat was initially tossed in for the machine gunner. By the end of that year, some 1,450 two-seaters had been produced, and all the airplane factories were producing the two-seaters by February 1943. The more powerful AM-38F boosted engine was installed, giving the craft more than 1,750 horsepower on takeoff to offset the added weight.

The two-seater was also upgunned with two 37mm cannons mounted in streamlined pods under each wing. This gave the Soviet craft twice the cannon power of the American Bell P-39 Airacobra with its single 37mm cannon that the United States provided to the Soviet Union under the Lend-Lease Act.

A Sturmovik’s cannon could certainly take out a light tank and had a decent chance of doing the same with a medium tank. The Soviets found that they reportedly could take out a PzKpfw. V Panther medium tank and even a heavy PzKpfw. VI Tiger with a well-placed hit with an armorpiercing shell on the more thinly clad rear of the vehicle. Aiming the guns, though, was difficult, and the heavy recoil necessitated re-aiming the cannon after only a few shots.

As it turned out, by late 1943 the use of 37mm cannons on the Sturmoviks was largely being phased out with the introduction of antitank bomblets (PTABs), which proved exceptionally effective against tanks, artillery, and hardened encasements.

The PTABs were small 5.5-pound armorpiercing shaped bomblets capable of penetrating the top armor of any of the German tanks then in the field. The PTABs were dropped from altitudes as low as 320 feet and had a destructive zone of some 50 by 230 feet. They were first used in the Battle of Kursk and were found to be effective because the bomblets were much easier for inexperienced pilots to use that other antitank weapons. They also eliminated the down time needed to re-aim the cannon.

The initial use of the PTABs proved to be a tactical surprise, reportedly dumbfounding the Germans and undermining their morale. The PTABs were soon put into mass production and widely used from then on against German ground units, railway cars, bridges, and artillery units. For their part, the Germans responded to the new weapon by spreading out their tank formations, which in turn lessened their effectiveness and substantially compounded command and control issues for the Nazi tankers.

The Soviets did not completely give up on the 37mm-armed Sturmoviks, and they were employed in a number of circumstances, including against enemy naval forces. Other Il-2s were modified to become torpedo bombers.

The two-seater did undergo additional changes as the war progressed, including the use of swept back wings to offset the change in the center of gravity caused by the addition of the rear gunner. This led to much better control and stability and eliminated a complicated bungee spring and counterweight system on the elevator controls. The swept wing version went into production in late 1943, and the straight winged Il-2s were completely phased out of the production lines early the following year. By the end of the war, some 17,000 of the two-seater swept wing planes had been built, or 47 percent of the total produced.

The “Wheel of Death”

Not only did the plane evolve over time, but Soviet tactics did as well. Early war tactics involved a handful of Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmoviks flying often unescorted against strong German defenses only to suffer significant losses from both enemy planes and flak. Early in the war the experienced German pilots found it relatively easy to take down inexperienced Soviet pilots flying without fighter escort. Attempts to have the Il-2s dive on targets from altitudes of 2,000 to 3,000 feet did result in increased efficiency but with increased losses from enemy planes and ground fire.

The Soviets resorted to having the ground attack aircraft fly in larger groups of eight to 12 planes, enabling the Il-2s to better protect each other by flying in a defensive circle, which the Germans called the “Wheel of Death.” Attacking in such groups also helped assure that the volleys of the somewhat inaccurate rockets would strike vital components of the German defenses. The changes also included having a few of the Il-2s initially attack German artillery positions to help lessen flak damage in subsequent attacks. The pilots also developed a zig-zag system of attack that reduced chances of being hit. Studies conducted on a Soviet test range revealed that it was more effective if rockets were used on the first run, followed by secondary runs with bombs and following runs with guns.

Soviet flyers also discovered that while the Ilyusha was slower in a turn than German fighters it could outturn them in a half-turn maneuver, which enabled them to become the attackers. They also learned to suddenly slow the Sturmovik so the German fighters would zip past and then become victims of the Soviet planes’ heavy cannon and machine-gun fire. They also learned to sideslip the Il-2 in a 20-degree bank, creating aiming problems for the Germans.

By late 1943, Soviet tactics had evolved to the point where the Sturmovik had become a much feared weapon. Pilots had gained significant experience, and the Germans were forced to rely on fewer pilots with often inadequate training because of attrition in the East and escalated Allied pressure in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy. With fewer enemy fighters in the air, the Wheel of Death was modified from a defensive mode to a nearly purely offensive one as Soviet attackers circled a target with round after round of blistering fire until the targets were obliterated or the Il-2s ran out of ammunition.

These attacks would sometimes last more than 90 minutes, and as the war progressed even more Il-2s were added to the deadly wheels, often resulting in elongated formations of planes. The addition of radio sets also simplified and greatly improved aerial communications in the increasingly crowded skies.

After the war, the rear wooden fuselages were replaced with metal, which extended the useful life of many Il-2s. A large number were used by foreign countries well through the mid-1950s.

Author Phil Zimmer is a U.S. Army veteran and a former newspaper reporter. He has written on a number of World War II topics.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments