By Charles Gutierrez

The U.S. 9th Armored Division arrived in the European Theater of Operations in late October 1944 as a reserve for Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton’s VIII Corps. On December 9, 1944, Brig. Gen. William Hoge’s Combat Command B (CCB) of the 9th was attached to V Corps to support the 2nd Infantry Division in its planned attack through the Monschau Forest as part of the U.S. Army’s strategy to capture or destroy the Roer River dams.

For this mission, CCB consisted of the 14th Tank Battalion, the 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, the 16th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, and miscellaneous smaller units vital to any major command. General Hoge set up his command post in the Belgian village of Faymonville, approximately 12 miles north of the town of St. Vith, unaware of the pivotal role his command was to play in a very different battle.

The German plan for the attack through the Ardennes, an offensive that would forever be known as the Battle of the Bulge, was to be accomplished in the conventional manner. Infantry divisions would begin the attack along the entire length of a 50-mile front, forcing a rupture along the Allied line and giving the German panzer divisions freedom of movement in the unoccupied ground beyond the front.

Since speed was the key to success of the German plan, two panzer armies would spearhead the offensive. One, the Sixth Panzer Army, was commanded by SS Obergruppenführer (brigadier general) Josef “Sepp” Dietrich, and the other, the Fifth Panzer Army, was commanded by General Hasso von Manteuffel. The Fifth and Sixth Panzer Armies were to advance abreast, cross the Meuse River, and then drive for the Belgian port city of Antwerp, a major staging and supply center for the Allied armies in western Europe. Overall operational command for the offensive fell to Field Marshal Walther Model.

The Sixth Panzer Army, with the 15th Army on its right, was to launch the main attack between Monschau in the north and Prum in the south. It was to cross the Meuse on both sides of Liege before advancing on to Antwerp. South of Sixth Panzer Army was General Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army, with the Seventh Army on its left. Fifth Panzer was to attack from Prum in the north down to Bitburg and Bastogne in the south. The village of St. Vith lay approximately 12 miles behind the front lines on December 16, 1944, the day the offensive code-named Operation Watch on the Rhine began. The town was also in Fifth Panzer Army’s area of advance.

St. Vith is built on a low hill surrounded on all sides by slightly higher rises. Its population in 1944 was about 2,000, and its citizens were very much pro-German. Six paved or macadam roads converged at St. Vith, but none of these was considered by the Germans to be a major military trunk line. The closest of the northern German armored thrust routes ran through Recht, about five miles northwest of St. Vith. The closest primary German armored thrust route to the south ran through Burg Reuland, also about five miles from St. Vith.

The capture of St. Vith was, however, important for three other reasons: to ensure the complete isolation of Allied troops that might be trapped on a nearby ridge called the Schnee Eifel; to cover the German supply lines unraveling behind the armored corps to the north and south; and to feed reinforcements laterally into the main thrusts by using the St. Vith road net. Thus, the Fifth Panzer Army commander ordered that St. Vith be taken no later than the second day of the offensive.

The job of capturing St. Vith went to the Fifth Panzer Army’s 66th Corps, commanded by General Walther Lucht. The corps consisted of two infantry divisions. One, the 18th Volksgrenadier Division, was holding the northern reaches of the Schnee Eifel. The other, the 62nd Volksgrenadier Division, bore the number of an infantry division destroyed on the Eastern Front, which had been reconstituted. It was at full strength and supplied with the latest equipment. The 62nd, like the 18th, included three regiments of two battalions each. Its mission was to break through to the south of the 18th Volksgrenadier in the Grosslangenfeld-Heckhuschied sector, advance northwest on a broad front, and seize the Our River crossing at Steinebruck, five miles southeast of St. Vith.

Once the bridge at Steinebruck was seized, the 62nd was to support the 18th Volksgrenadier Division’s drive on St. Vith by blocking the western and southern routes in and out of the town.

At approximately 0530 on December 16, eight German armored divisions and 13 infantry divisions launched their all-out attack on five divisions of the U.S. First Army. The German armored and infantry attacks were preceded by the shelling of the American positions with at least 657 light, medium, and heavy guns and howitzers and 340 multiple rocket launchers. On this day, CCB of the 9th Armored Division was still in its assembly area in the vicinity of Faymonville. Its supporting field artillery battalion was at Kalterherberg, two miles south of Monschau, engaged in firing missions for the 2nd and 99th Infantry Divisions. The American plan was that once the 2nd Infantry Division reduced the German defenses at the Wahlerscheid crossroads, CCB was to spearhead a drive to the reservoirs north of Gemund and Schleiden.

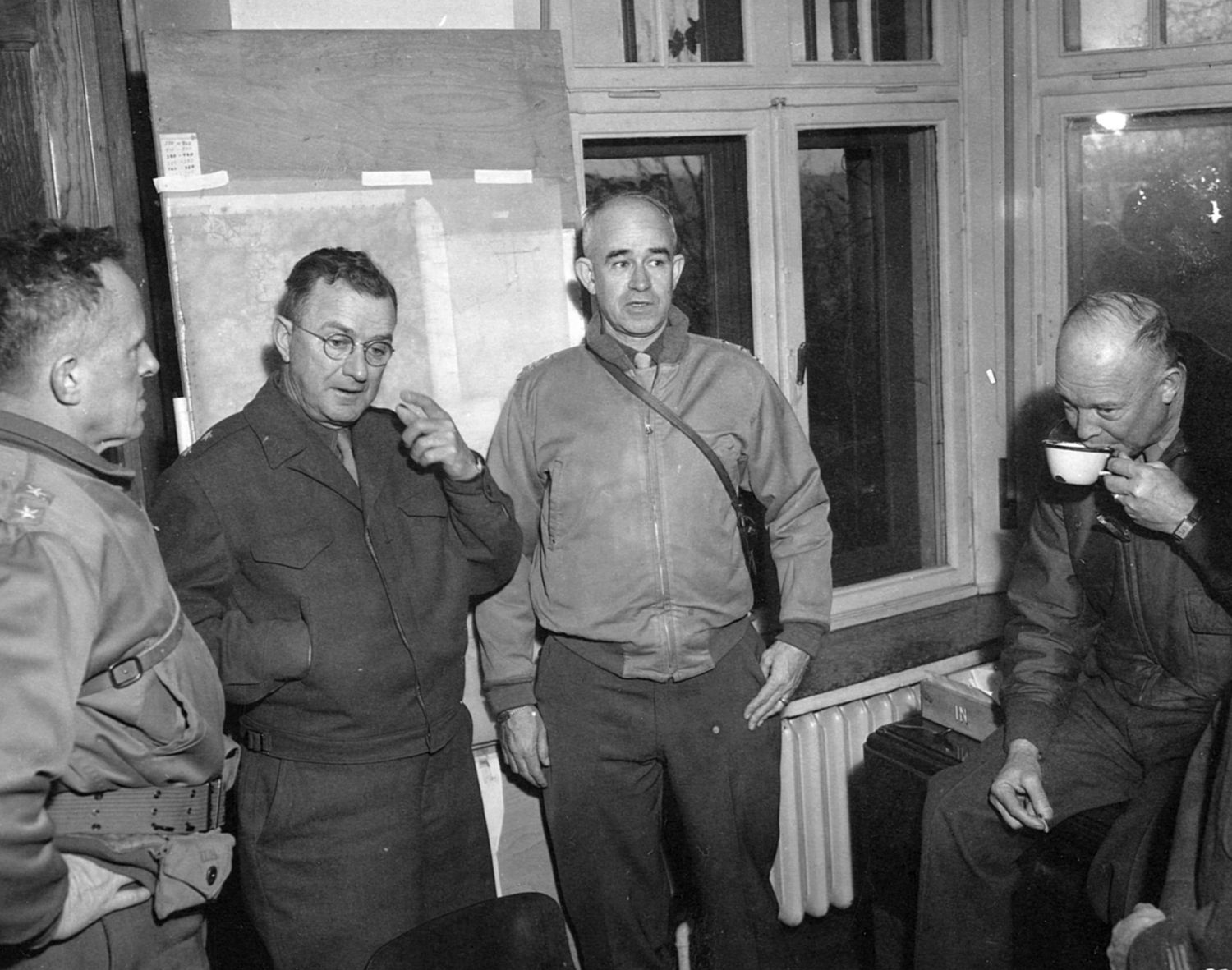

commander of the VIII Corps, and Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, commander of the 12th Army Group.

To this end, General Hoge was in the town of Monschau to check on the possibility of getting his command across in that area. While making his reconnaissance at Monschau he received an urgent message to call V Corps headquarters. The message was that his command was now back with VIII Corps and that he was to go to St. Vith and report to Maj. Gen. Alan W. Jones, commander of the newly arrived 106th Infantry Division.

On his way to St. Vith, General Hoge stopped in Faymonville to alert his command to be prepared to move immediately. Hoge departed Faymonville at approximately 1800, arriving at General Jones’s headquarters in the St. Josephs Kloster about a half hour later. Within the Kloster, General Hoge found a division headquarters staff in a state of disarray and confusion. No one knew what was happening. Clerks were running everywhere and junior staff officers were arguing among themselves; upstairs, however, Hoge found General Jones remarkably composed.

Jones explained to Hoge that his division was being attacked along its entire front and that two of his three regiments, the 422nd and the 423rd, had been partly surrounded in the Schnee Eifel area just east of Schoenberg. What Jones did not tell Hoge was that in one of those regiments his own son was serving at regimental headquarters.

Initially, General Jones wanted Hoge to move his command into the Losheim Gap at Maderfeld and arrive there at dawn on December 17 to counterattack and erase the enemy penetrations that were threatening 106th Division positions on the Schnee Eifel. Soon after General Hoge left 106th Division headquarters for the drive back to Faymonville, Jones received a call from Middleton informing him that a combat command of Brig. Gen. Robert Hasbrouck’s 7th Armored Division would be arriving at St. Vith at 0700 on the 17th. The entire division was to follow shortly thereafter.

Slayden had Serious Doubts About His Mission, but Kept Quite

Although General Jones was deeply worried about his two regiments on the Schnee Eifel, he was also highly concerned about the German advances in the Winterspelt area where his 424th Infantry Regiment was defending. Situation reports suggested that the Germans were intent on crossing the Our River at Steinebruck. Now with a new armored combat command due to arrive at 0700 hours the next day, and with the rest of the division to follow, Jones believed he would soon have the potential to deal with both the Schnee Eifel and Winterspelt emergencies. Therefore, he decided to use the 9th Armored at Winterspelt, since capture of that area by the Germans would open to the enemy a direct route to St. Vith, a route even shorter than that leading from the Schnee Eifel.

Thus, the job of rescuing the two trapped infantry regiments on the Schnee Eifel passed from the 9th to the 7th Armored Division.

At St. Vith, Lt. Col. William H. Slayden was with Jones when Jones received the call from Middleton concerning 7th Armored Division support. Slayden had been sent to Jones by Middleton as an adviser until the 106th Division could become acclimated. Slayden, knowing that the nearest units of the 7th Armored Division were at least 60 miles away in the Netherlands, had serious doubts that a whole combat command could reach St. Vith on the 17th, much less by 0700 hours. However, he kept these misgivings to himself.

At CCB, 9th Armored Division’s headquarters in Faymonville, General Hoge was just finishing up his briefing for his command’s move to the Losheim Gap and Manderfeld when the call came through from General Jones informing him of 9th Armored’s new Winterspelt mission. Since the move from Faymonville to Winterspelt involved a greater distance, Hoge decided to get his command on the road immediately. The time was approximately 1800 on Saturday, December 16, when Combat Command B of the 9th Armored Division began its move to St. Vith.

At about noon that day, the 62nd Volksgrenadier Division’s 190th Regiment had broken through north of the 424th Infantry’s Cannon Company. The Germans were now on the high ground north of Eigelscheid overlooking the road to Winterspelt. General Frederich Kittel, the division commander, ordered his mobile battalion up from his 164th Regiment reserve at Pronsfeld and into the attack along the Winterspelt road. This battalion hit the 424th’s Cannon Company at the Weissenhof crossroads. Outnumbered and in danger of encirclement, the cannoneers and their rifle support from C Company made a platoon-by-platoon withdrawal toward Winterspelt. By dark, just as General Hoge’s command was getting underway from Faymonville, Kittel’s mobile battalion and infantry from the 190th Regiment were closing in on Winterspelt.

At the close of the first day of battle, General Lucht could look with some satisfaction at the day’s events, although his 62nd Volksgrenadier Division had yet to break through the American line. Lucht anticipated that the Americans would counterattack the next day, but that their reaction would be too late to avoid complete encirclement.

At about 0115 on December 17, a platoon from 9th Armored’s D Troop, 89th Recon was detailed to proceed through St. Vith in a southeasterly direction and seize the high ground along Highway N27 south of Steinebruck. The troop was to hold until relieved by the 27th Armored Infantry Battalion (AIB) and then reconnoiter farther down the road toward Winterspelt. However, this platoon never completed its mission. While on its way, the platoon was commandeered by a colonel from the 106th Division. The colonel ordered the troop east along the road to Schoenberg to delay a German tank and infantry team approaching St. Vith from that direction. The platoon lost four men missing and two wounded in the ensuing engagement.

The Command’s main body was led by the 27th AIB with B Company in front, followed by Headquarters and C Company. Company A of the 27th AIB had been assigned to the 99th Infantry Division and was in the process of being retrieved when the march to St. Vith began. Next came B Company, 9th Armored Engineers; the 16th Armored Field Artillery; B Company, 482nd Antiaircraft Artillery; and the 14th Tank Battalion. Elements of D Company, 89th Recon screened the flanks.

General Lucht’s plan for December 17 was simple. A mobile battalion of the 18th Volksgrenadier Division was already moving on Andler to seize the Schoenberg bridge and the road to St. Vith. The southernmost battle group of the 18th Volksgrenadier would also undertake a mobile thrust and, finally, the 62nd Volksgrenadier would break loose at Heckhuscheid and drive for the Our River Valley.

The leading vehicles of General Hoge’s command entered St. Vith on Sunday morning just as dawn was breaking and halted close to the 106th Division’s command post at the St. Joseph Kloster. Inside the command post, General Hoge learned that the Germans had launched a heavy assault on Winterspelt against the men of the 424th Infantry. General Jones wanted Hoge to use the infantry of his 27th AIB to seize the series of hills near Winterspelt while the 14th Tank Battalion was to remain west of the Our River for use as the situation developed. The ultimate objective was to open an escape route for the soldiers of the 424th. An attack to the east by the 7th Armored Division could then relieve the two surrounded regiments of the 106th.

Colonel Alexander D. Reid, commander of the 424th Infantry Regiment, had reason to fear encirclement. During the early hours of December 17, the Germans laid heavy mortar and artillery fire on the front-line positions of his regiment. The situation on Reid’s left flank was unclear, and the Germans were attacking in considerable force against his right flank. Elements of the 62nd Volksgrenadier had taken the eastern half of Winterspelt during the night, and at daybreak reinforcements finally drove Colonel Reid’s 1st Battalion from the village.

The 424th Infantry had its back to the Our River, and if the Germans seized the bridge at Steinebruck and spread along the far bank his regiment would be hard pressed to effectively withdraw. Communications with division headquarters in St. Vith were limited to liaison officers running along a road now being shelled by the Germans.

Although the 62nd Volksgrenadier Division drove the American defenders from Winterspelt, all was not going well for the Germans. The 424th Infantry still blocked the road to the Our River and Steinebruck. General Lucht hurried to Winterspelt to get the 62nd Volksgrenadier moving to the Our. Although the 62nd Volksgrenadier captured Winterspelt, its losses were high and its left regiment had made little headway in the Heckhuschied sector.

On the road to Winterspelt, General Hoge soon learned that the situation there was worse than General Jones had described. The column came upon stragglers from the 424th Infantry retreating in disarray toward St. Vith. Hoge managed to stop the stragglers, and soon a provisional company of men from the 424th was formed to reinforce the 27th AIB on its march toward the Our.

With the unexplained disappearance of D Troop from the 89th Reconnaissance Platoon, Company B, 27th AIB became the leading element. At approximately 0930 on December 17, B Company was the first 9th Armored Division unit to cross the Our River. Soon after its crossing, B Company ran into German infantry dug in along the high ground overlooking the village of Elcherath.

Rather than Spill Blood Needlessly to Take Meaningless Ground, Hoge Called Off the Attack on Winterspelt

Staff Sergeant Frank Mykalo knocked out a German machine-gun position, enabling the men in the lead half-tracks to dismount and deploy along the side of the road. In the 27th AIB’s move to take the high ground, B Company advanced along the center of the road. A Company moved south under the protection of the high river bank, while C Company deployed along the left side of the road as the enveloping company. During the assault, B Company suffered about 40 casualties including its commanding officer, Captain Henry D. Wirsig.

During the 27th AIB’s assault, a call went out for the 14th Tank Battalion to join the action. In minutes, a platoon of medium tanks from A Company of the 14th rolled across the bridge at Steinebruck and placed high explosive and heavy machine-gun fire on the enemy’s position in the woods and along the draw. By noon, the 27th AIB, with the help of Company A, 14th Tank Battalion, had retaken that first stretch of high ground. By mid-afternoon, General Hoge ordered his infantry to halt and dig in. Counter to the plan laid out earlier by General Jones, Hoge had decided to launch his attack on Winterspelt with the entire 14th Tank Battalion as the lead element rather than with the more vulnerable infantry of the 27th AIB.

The 14th Tank Battalion was on its way to the Steinebruck bridge when Brig. Gen. Herbert T. Perrin, assistant commander of the 106th Infantry Division, drove up carrying a message from General Jones. Perrin told General Hoge, “You can continue this attack on towards this back country, but you must be back on this side of the river by nightfall.”

Hoge could not see much sense in making an attack, taking ground, and then turning right around and coming back, especially if the attack was successful. So, rather than spill blood needlessly to take meaningless ground, Hoge called off the attack on Winterspelt. His troops remained in place, and the pullout to the west side of the Our River began at dusk. Fortunately for Colonel Reid, word came at about 1730 that his 424th Infantry Regiment was to withdraw immediately.

By the end of the day, the 27th AIB had withdrawn through Steinebruck without casualties despite enemy shelling of the village. Both B and C Companies pulled back to the vicinity of Neidingen, near the battalion command post, while the 14th Tank Battalion established a perimeter defense around its assembly area near Breitfeld about halfway between the Our and St. Vith. Troop D, 89th Recon held the sector from Steinebruck to Weppeler while A Company, 27th AIB put up a defensive line anchored on the high ground east of Maspelt. Between these units, a place was found for the provisional company composed of the 424th Infantry stragglers.

While 9th Armored was thus engaged in the Winterspelt area during the morning hours of December 17, Brig. Gen. Bruce C. Clarke, commander of CCB, 7th Armored Division, arrived at General Jones’s command post in St. Vith at approximately 1030. By this time the Germans had essentially closed the trap on the two infantry regiments on the Schnee Eifel. Jones wanted Clarke to counterattack immediately with his combat command “and break that ring that these people have closed around the Schnee Eifel.”

It was a clear disappointment to Jones when Clarke told him that he, his operations officer, his aide, and his driver were the only representatives of the 7th Armored Division to have reached St. Vith at that time. Furthermore, General Clarke had no idea when his command would arrive.

During the rest of the day and on into the evening of December 17, CCB, 7th Armored moved into St. Vith and began a buildup that resembled a large horseshoe on the high ground to the east of the village. Although the 7th Armored Division was finally arriving, General Jones had been led to believe that the whole division would arrive in St. Vith starting at 0700. Jones had been counting on this when he sent Hoge’s 9th Armored Command to Winterspelt rather than Schoenberg. It appeared now that the fate of his two northern regiments was sealed.

Late on December 17, General Manteuffel was concerned with the lack of progress in his attack beyond the Schnee Eifel toward St. Vith. Since St. Vith should have been taken on December 16 or the 17th at the latest, he decided to leave his command post at Waxweiler and spend the night with the 18th Volksgrenadier Division at Schoenberg. While walking to avoid the traffic congestion, Manteuffel encountered his superior, Field Harshal Model.

Model informed Manteuffel that he would be given the Führer Escort Brigade, which was nearly equal in strength to an American light armored division, for the upcoming assault on St. Vith. The brigade had 9,000 men, Mark IV tanks, assault guns, 104mm and 105mm artillery, 88mm antiaircraft guns, and a number of heavy automatic weapons batteries.

Troop D, 89th Recon had positioned its troop headquarters and first platoon to cover the bridge over the Our. During the night, the troopers experienced harassing fire from light and medium artillery and could observe enemy infantry and at least four tanks moving along high ground to the south of the river. At approximately 0100 on December 18, a German force of about 30 men tried to cross the Our at Steinebruck after a brief artillery barrage. They were repulsed by machine-gun fire. A second attempt on the bridge, made by about 40 men four hours later, was also thrown back by machine-gun fire. Both assault groups suffered heavy casualties. Fire from the 16th Field Artillery broke up other enemy formations trying to assemble on the high ground to the south. One German tank was seen going up in flames.

The provisional company of 424th stragglers disappeared during the night. To cover this dangerous gap in the line C Company, 27th AIB was ordered to the Our between Troop D, 89th Recon and Company A, 27th AIB. On its way to the new position, C Company came under a sudden artillery and rocket barrage in the village of Lommersweiler. Unable to advance, it pulled back to the nearest high ground and dug in.

Sometime later that Monday morning, General Hoge sent his liaison officer to St. Vith to learn the dispositions of CCB, 7th Armored Division. En route, the officer was approached by a member of General Clarke’s staff who told him that German tanks were approaching St. Vith along the road from the north. He was also told that all that stood in their way were two troops of the 87th Recon Squadron, 7th Armored’s 87th, and a few antiaircraft half-tracks. The staff officer wanted to know if 9th Armored could spare some desperately needed help.

After listening to the information provided by General Clarke’s staff officer, General Hoge decided to go to St. Vith himself to assess the situation. Before departing, however, Hoge gave orders to Lt. Col. Leonard E. Engeman, commander of the 14th Tank Battalion, to get a strong force ready to move out to assist 7th Armored should it become necessary. Once in St. Vith, Jones explained that only the leading elements of the 7th Armored Division had arrived thus far and that St. Vith’s northern approach was under attack. Hoge immediately got on the phone and ordered Engeman to move out.

Engeman set out with two task forces to meet the enemy. One task force was made up of A and B Companies of the 14th Tank Battalion, B Company of the 482nd Antiaircraft Artillery, and another platoon of the 14th. The second task force consisted of B Company of the 811th Tank Destroyers. Both task forces reached St. Vith shortly before noon on the 18th to find not one, but two German attacks moving against the town.

One task force encountered reconnaissance probes on N27 conducted by units of the 1st SS Panzer Division approximately 1,000 yards north of St. Vith. The Sherman tanks of B Company repulsed the enemy with fire from their 76mm guns. When B Company pulled back to refuel and rearm, A Company passed through to take up the fight. The second task force hit another probe by the 1st SS Panzer and pushed it out of Hunningen.

“Why in the World When I had Only 2,500 Men Available to My Command on December 17, did You not Just Execute a Powerful Frontal Assault and Overrun Me?”

Both American units were able to drive forward, and the Shermans knocked out six German armored vehicles. The two task forces held onto their respective positions on N23 and N27, deflecting all German armored attempts to penetrate St. Vith, until they were relieved late in the afternoon by CCB, 7th Armored Division. By dark, Lt. Col. Engeman and his two task forces were back in their assembly area in the vicinity of Breitfeld.

During ceremonies observing the 20th anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge, General Clarke was able to talk to General Manteuffel and discuss German operations against St. Vith. Clarke asked, “Why in the world when I had only 2,500 men available to my command on December 17, did you not just execute a powerful frontal assault and overrun me?”

Manteuffel answered, “We estimated that we were up against a division, and perhaps against an entire corps. We made several probing attacks, and every time we went into your position, we encountered armor. Our preliminary briefings had told us that there would be no armor in our path. When you get surprised like this, you become cautious.” Undoubtedly much, if not most, of the armor encountered by Manteuffel’s probing actions during the early days of the German offensive belonged to CCB, 9th Armored Division.

South of St. Vith, even as Lt. Col. Engeman’s task forces were responding to the 7th Armored’s cry for help, Germans of the 62nd Volksgrenadier Division were trying to get across the Our River at Steinebruck and hit St. Vith from that direction. The bridge at Steinebruck was intentionally left intact by General Hoge on the outside chance that some of the American troops trapped in the vicinity of the Schnee Eifel might be able to maneuver their way there.

However, by noon on December 18 it was quite apparent to Hoge that the Germans infiltrating across the river were converging on the bridge in such numbers that it had to be blown. Under cover of automatic weapons fire from a platoon of light tanks, Sergeant Eugene Dorland and two other men from the engineers went into the cold, bullet-splattered water carrying three cases of TNT and placed their charges on the south abutment of the bridge. The resulting blast damaged the bridge to such an extent that the Germans would not be able to bring vehicles across for at least 24 hours.

Although the bridge over the Our was blown, the German presence kept growing. At about 1330, three German self-propelled guns and 19 or 20 horse-drawn artillery pieces went into position on the high ground 800 yards to the southeast of Steinebruck. After putting down a heavy concentration of artillery fire, the Germans moved their infantry across the river east of the position held by the 2nd platoon of D Troop, 89th Recon. The troop’s request for armored support was denied by General Hoge because his tank companies sent north to help the 7th Armored had not yet returned and no reserve was on hand.

However, Company B, 27th AIB was sent to help ease the situation, covering the cavalry’s left flank. With the enemy inside Steinebruck and excellent direct fire by the German artillery, what was left of 2nd Platoon, 89th Recon withdrew along the St. Vith road. All but five troopers of 2nd Platoon were lost to enemy action.

The 9th Armored Division’s position at the Our was no longer tenable. Because the Our had ceased to be a barrier anywhere else, General Hoge felt that there was little to gain in continuing to overextend his command to hold the low ground along the river. Having first conferred with General Jones, Hoge ordered a withdrawal from the river to begin after nightfall. CCB’s new position blocked the main Winterspelt-St. Vith highway and the valley of the Braunlauf Creek, a second natural corridor leading to St. Vith. CCB, 9th Armored was linked on its left with CCB, 7th Armored and what was left of the 424th Infantry Regiment on its right.

Although the Germans were quick to build up beyond the Our River after the American withdrawal, they made no immediate moves against the new American line. Rebuilding the blown bridge to get their assault guns across was their first priority.

The defense of St. Vith was now achieving some kind of order in contrast to the chaos that had reigned during the previous three days. The area being defended was beginning to take the form of a large horseshoe, its axis running approximately northeast to southeast. The northern prong of the horseshoe was composed of CCB, 7th Armored Division from Poteau and Vielsalm. The rounded portion of the horseshoe was composed of Colonel Dwight Rosebaum’s CCA, 7th Armored between Poteau and Rodt and General Clarke’s CCB, 7th Armored in the very center protecting St. Vith.

The southern prong was defended by General Hoge’s CCB, 9th Armored with the weakened 424th Infantry Regiment tied in and bent back protecting Burg Reuland. The greatest danger existed in the 424th’s position because the regiment’s flank lay vulnerable to attacks by the 116th Panzer Division to the south. The distance from Burg Reuland on the southeast to Poteau on the northwest was about 10 miles with only a single secondary road as a line of retreat for thousands of men defending the horseshoe against attack from three directions.

Early on the 19th, the Germans made reconnaissance probes. At about 0930, the enemy attacked St. Vith from Hunningen to the north, apparently in an effort to envelop Clarke’s left flank. The fight lasted for more than three hours before the Germans withdrew, leaving one burning tank and approximately 150 dead. Having failed to find a soft spot to the north, the Germans then moved against Hoge’s 9th Armored command in the south; however, even before this attack got going three German tanks were knocked out and the rest of the probing force withdrew.

Manteuffel had hoped for considerably more on the 19th. The reason for this comparative respite was due to the fact that the roads to the German rear were completely jammed. Adding to the slowdown of operations against St. Vith, the 18th Volksgrenadier Division was still using two of its three regiments and all but one of its artillery battalions against the two trapped 106th Infantry Division regiments on the Schnee Eifel. It would be unable to turn its full strength on St. Vith until the American surrender in that area.

Manteuffel met near Wallerode with Model and Lucht that day. There was little they could do other than vow to get the attack moving early on the 20th. By that time the 62nd Volksgrenadier Division should have the bridge at Steinebruck rebuilt, at least two regiments of the 18th Volksgrenadier Division should be forward, and the Führer Escort Brigade should be ready to make the principal thrust down the Ambleve highway into St. Vith. Moreover, at least a regiment from the 1st SS Panzer Division was in sporadic conflict with the American defenders in the Recht-Poteau area and, in the south, elements of the 560th Volksgrenadier Division, part of General Walter Krueger’s 58th Panzer Corps, were also identified as pushing against American forces in the St. Vith salient.

General Jones and his staff had pulled out of St. Vith on the morning of the 18th for Vielsalm. Since General Hoge was supposed to be under Jones’s command and did not understand the overall situation around St. Vith, he decided to find out exactly what was going on. ‘

Immediately After the Companies Began to Move, They Found Themselves Under Attack

During the afternoon of December 19, Hoge visited Clarke’s command post in St. Vith and expressed his frustration with the current chain of command. After Clarke and Hoge settled upon a mutually supportive command structure, Clarke noted that Hoge’s command was, for the most part, forward of a railroad track built on a high embankment. Should 7th Armored lose St. Vith, 9th Armored would be unable to withdraw on its own axis. Hoge and Clarke agreed that Hoge’s entire command should be withdrawn west of the railroad tracks. To execute this maneuver, Hoge’s entire command would have to move all the way up to St. Vith and back down again. The move would also have to be done under the cover of darkness in severe wintry conditions.

Orders for CCB, 9th Armored to move to a new defensive position were issued at 1600. The supply trains led the way north on N27 to St. Vith. They were followed in order by the half-tracks and other vehicles of the 27th AIB, the tank companies, the antiaircraft company, and the engineers. The foot elements of the 27th AIB were then to move out with Company B, 482nd Antiaircraft Artillery and some light tanks from Company D, 14th Tank Battalion following behind Company B, 27th AIB.

The move had scarcely begun when an enemy attack hit the junction between Company B, 27th AIB and Company D, 14th Tank Battalion. The guns from a platoon of Shermans, the antiaircraft company, and a mortar platoon supplied a covering barrage, which broke up the German assault and inflicted heavy casualties. The circuitous march up one road and down another led to a new line just a few hundred yards to the west of the old one and was miraculously carried out while under attack without the loss of any men or equipment.

By midnight on the 19th, the horseshoe- shaped defense of St. Vith had taken form. The sector now defended by CCB, 9th Armored extended across five miles of rugged terrain that was primarily held by the three infantry companies making up the 27th AIB. Company B was stationed east of Galhausen and maintained contact with the nearest elements of the 7th Armored Division on 9th Armored’s left flank. Situated next to B Company were Company A, 27th AIB and Company D, 14th Tank Battalion. Company B of the 9th Engineers and D Company of the 89th Recon joined the line to supplement the armored infantry. The CCB command post was moved to Neubruck, a small group of farmhouses on Braunlauf Creek about two miles southwest of St. Vith. No reinforcements were expected. The next move was up to General Lucht and his corps. Manteuffel’s operation in the St. Vith area was already three days behind schedule.

On the morning of the December 20, three tank destroyers were placed in support of Company C, 27th AIB. Approximately three hours later a German company marched out of Neidingen and along the road leading straight into C Company’s position, apparently totally unaware of 9th Armored’s recent change of position. The armored infantrymen kept themselves well hidden until the column was directly in front of them and then opened fire. The surviving Volksgrenadiers fled in disarray. That night, infantry patrols found German medics removing their wounded.

Late on the 20th, patrols of the 82nd Airborne Division, on the other side of the Salm River, established contact with patrols of the 7th Armored Division. With this contact, all units in the vicinity of St. Vith, including 9th Armored Division forces, passed to the command of Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway’s XVIII Airborne Corps.

December 20 was a day of disappointment for the Germans around St. Vith. Generals Manteuffel and Lucht had planned an all-out attack to take St. Vith starting at daylight with a three- pronged envelopment by the 62nd Volksgrenadier Division against 9th Armored positions in the south. The 18th Volksgrenadier Division was to attack along the two roads from Schoenberg, with the Führer Escort Brigade assaulting from the north. In addition, elements of the 116th Panzer Division and the 560th Volksgrenadier Division were moving against the weakly held southern flank of St. Vith defended by remnants of the 424th Infantry Regiment of the 106th Infantry Division and the 112th Infantry Regiment of the 28th Infantry Division.

However, the monumental traffic jams in the Losheim Gap and at Schoenberg continued to delay both the 18th Volksgrenadier Division and the Führer Escort Brigade, and not until after daylight on the 20th would a bridge be ready at Steinebruck for the 62nd Volksgrenadier Division. Those factors dictated that at least another 24 hours would be needed before a major assault on St. Vith could begin.

When Model released the Führer Escort Brigade to General Manteuffel, he thought that he would be able to gain quick access to the St. Vith road network. Once St. Vith was taken, Model intended to drive the brigade swiftly for the Meuse River or cut behind the opposition on the Elsenborn Ridge that was bottling up the Sixth Panzer Army. Moreover, it was expected that General Lucht’s two infantry divisions would be forwarded to the Salm River sector as right-wing cover for two panzer corps.

Such was not the case, however, and by the evening of the December 20, the Germans were feeling the growing negative effects of the St. Vith salient. The failure to capture St. Vith was preventing the linkup of the Fifth and the Sixth Panzer Armies. In addition, the massive road jam caused by the inability to pass through St. Vith was creating acute shortages of gasoline and ammunition well to the west of St. Vith. Accordingly, that evening Sixth Panzer Army commander Dietrich issued orders to the 2nd SS Panzer Corps to move to the south so that parts of that corps could assist Manteuffel in taking St. Vith. The men of the 2nd SS Panzer Corps had expected to be on the Meuse by December 19, but on the night of December 20 the Americans still denied them access to St. Vith.

At daybreak on December 21, the Germans launched their first assault of the day on CCB, 9th Armored. The Germans attacked the center of the 27th AIB. This initial thrust carried the enemy approximately 400 yards into the battalion’s sector. The guns of two platoons of Company A, 811th Tank Destroyers were overrun. A scratch force made up of one platoon of riflemen from Company A, 27th AIB and a platoon from Company B, 9th Engineers were sent to contain the Germans. A platoon of medium tanks counterattacked, and the enemy retreated. By 1245, the original line was restored, and the antitank guns of Company A, 811th Tank Destroyers were recovered.

Farther to the north, in the 7th Armored sector, the pressure exerted by the enemy was also intense. By 1300 on the 21st, the entire line was ablaze with German artillery, rockets, tanks, and infantry. When a particularly heavy onslaught was launched against 7th Armored, near 9th Armored’s left flank, Company A, 14th Tank Battalion shifted its mediums to fire directly on Breitfield in support of its armored neighbor to the north. The 16th Field Artillery also pitched in, as did a battalion of 155mm howitzers sited around Commanster. Together they broke up the attack.

Although the Germans were facing stiff resistance all along the American defensive line, they were determined to take St. Vith. Late in the day, the Germans launched three major attacks, each directed along a main road leading into the town. At about 1700, the enemy attacked along the Schoenberg road from the east; at 1830, they came down the Malmedy road from the north, and at 2000, an attack started from the southeast along the Prum road. Each attack was preceded by an intense artillery barrage lasting from 15 to 35 minutes.

At Least 900 Soldier Dead or Captured

At about 2130, General Clarke phoned General Hoge to tell him that the enemy was entering St. Vith from the north and that his forces were withdrawing to form a new line northwest of the city. Since 7th Armored’s withdrawal meant that 9th Armored’s left flank would be in danger, the two generals agreed that Hoge would have to readjust part of his line to maintain contact with Clarke’s new rearward position. The village of Bauvenn was designated the linkage point for the two combat commands. In blinding snow and on slippery roads the tanks and infantry of CCB, 9th Armored headed for Bauvenn. Confusion, darkness, and mud slowed the move, but by morning a medium tank company and a platoon of riflemen had reached the village.

The 7th Armored had taken a beating in defending St. Vith. At least 900 soldiers who had stood in front of the town were either dead or captured. The division had lost four companies of armored infantry. This left General Clarke with only one full company of armored infantrymen.

Despite the loss of St. Vith, General Ridgway believed that the American armored and infantry forces defending St. Vith since December 16 could still hold. Ridgway’s 82nd Airborne was building a fairly firm line west of the St. Vith defenders that should prevent the Germans from cutting off the salient from the rear. He also hoped the 3rd Armored Division soon might attack to remove all threat of encirclement. Based upon this fairly optimistic view, Ridgway, shortly after midnight, ordered the entire St. Vith force to withdraw from its current positions and form a defensive ring west of St. Vith and east of the Salm River.

Ridgway’s plan was premised on the assumption that that the American forces in this goose egg-shaped defense could be supplied by air; however, whoever drew up the plan was thinking in terms of supply requirements for the lighter airborne divisions, not for fuel-hungry and shell-reliant armored forces. The troops were exhausted and spread out. The fortified goose egg ran nearly 10 miles in diameter, containing a mass of forest and only one decent road running northwest to southwest. This was no place to conduct a mobile defense with armor-heavy forces.

At 0200 on December 22, the Führer Escort Brigade launched its attack against the town of Rodt, a small village west of St. Vith. As a result of 7th Armored’s earlier regrouping, Rodt was the junction point between CCA of the 7th Armored under the command of Colonel Rosebaum and General Clarke’s CCB. Rodt was garrisoned by the service company of the 48th AIB and some drivers belonging to the battalion whose vehicles were parked there. Resistance by service company personnel in Rodt was fierce with every possible man—drivers, cooks, radio operators—employed in the defense; however, after nine hours of battle against the much superior German force, Rodt fell.

The fall of Rodt effectively split 7th Armored’s CCA from General Clarke’s CCB. Clarke pulled back his left flank to protect Hinderhausen, a key position on the emergency exit route to Commanster and Vielsalm.

Not long after Rodt fell to the Führer Escort Brigade, an attack came against the 7th Armored from the direction of Recht. Although it was beaten off, the attacking Germans were identified as new to the area, soldiers of the 9th SS Panzer Division, a cause for considerable concern at this point in the battle.

After learning of the attack by the Führer Escort Brigade, Brig. Gen. Hasbrouck, commander of the 7th Armored Division, sent a message to General Ridgway urging withdrawal, which in part read, “P.S. A strong attack has just developed against Clarke again. He is being outflanked and is retiring west another 2,000 yards refusing both flanks…. Hoge has just reported an attack….” Two regiments of the 62nd Volksgrenadier Division attacked 9th Armored positions early that morning, their goal to gain the Salm River at Salmchateau.

After that morning’s enemy assaults, the line of the 27th AIB was reestablished west of Neubruck. Companies A and B held a line from Grufflingen to Hohenbusch with Company A, 14th Tank Battalion to their north. Troop D, 89th Recon and Company D, 14th Tank Battalion formed a line from Grufflingen to Thommen, and Companies B and C of the 14th Tank Battalion took up positions between Thommen and Maldange. General Hoge moved his command post to Commanster. That evening General Clarke also put his command into Commanster. The commanders were at the center of the Foret Domaniale du Grand Bois. This forest was criss-crossed only by trails.

The American armor of the 7th and 9th Armored Divisions plus supporting units were being pressed into an area in which motorized forces—tanks, half-tracks, self-propelled artillery, tank destroyers—operated with great difficulty. Despite nearly a foot of snow, the ground underneath was still soft, and with the passage of only a few heavy vehicles it was soon churned into a morass of mud. The mud had made the roads and open areas impassable for armored vehicles.

Although the American forces in the St. Vith area came under command of General Ridgway’s XVIII Airborne Corps, the Airborne Corps itself was under the command of Field Marshal Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, overall commander of the northern sector of the Bulge. Field Marshal Montgomery, believing that Ridgway’s Corps could not attack successfully toward Vielsalm and that the American forces within the goose egg could better be used in support of other forces committed to the northern shoulder defense, decided upon a general withdrawal.

Therefore, Montgomery ordered Ridgway to attack to the southeast until Vielsalm could be reached, ensuring an escape corridor for those trapped within the defense. At about midday, the field marshal sent a message to General Hasbrouck: “You have accomplished your mission—a mission well done. It is time to withdraw.”

Under the chain of the northern sector command, only General Ridgway was unsure of Field Marshal Montgomery’s decision to withdraw from the defense. In the early afternoon of the 22nd, he arrived at General Hasbrouck’s headquarters in Vielsalm to plan the withdrawal. Because Ridgway was not in total agreement with the withdrawal and to get a feel for the real situation on the ground, he and Hasbrouck made their way to General Clarke at Commanster.

After conferring with Clarke, Ridgway wanted to talk to one more man in whom he had supreme confidence—Brigadier General Hoge. Hoge and Ridgway had been on the West Point football team together when Ridgway had been the team’s manager. Ridgway knew Hoge to be calm, courageous, and imperturbable. If Hoge told him that the situation was bad, then without a doubt the situation was worse than he thought. Double-talking his identification over the radio with allusions to West Point football days, Ridgway gave Hoge a location at which to meet him.

During his meeting with Hoge, General Ridgway became convinced that defending this area any further would be futile. Although both men agreed that a withdrawal at this stage was the wiser decision, Hoge was skeptical that, given the weather and ground conditions, the defenders would be able to get out. Hoge pointedly asked Ridgway how it could be done. Ridgway answered, “Bill, we can and we will.” The withdrawal plan called for a general pullback west of the Salm River to an assembly area in the zone controlled by the 82nd Airborne Division in the vicinity of Lierneux.

Aside from the cold and mud, there was also the enemy to contend with. Before the day ended, renewed fighting broke out along the entire front. There was a bitter struggle to the south of Grufflingen, and the Germans were again active in the Neubruck area. General Clarke again called on the 9th Armored for assistance to help stiffen his line, and Hoge responded by sending the 3rd Battalion, 424th Regimental Combat Team. The two commanders agreed that even without the mud to contend with the withdrawal would have to be delayed simply because of heavy enemy pressure.

“A Miracle has Happened, General!”

At 0100 the 23rd, D Troop, 89th Recon lost an armored car and a jeep to antitank guns. At 0130 the 27th AIB was hit hard and the sector held by Company B, 9th Engineers was deeply penetrated, causing the armored infantry to fall back under the protective guns of Company A, 14th Tank Battalion. An assault on Thommen forced out the troops holding the town, and efforts to retake it failed. Another attack hit the left flank of 7th Armored.

Farther to the west, the 82nd Airborne, trying to keep a corridor open for the St. Vith defenders, was coming under intense pressure from the 2nd SS Panzer Division. In light of these circumstances, General Hasbrouck felt compelled to write to Clarke that unless the withdrawal began soon “the opportunity will be gone.”

During the night of December 22, a cold wind had begun to blow out of the east bringing what weathermen call a “Russian high.” Although both Clarke and Hoge noted it, they saw little hope that the ground might freeze in time to aid their withdrawal, but after receiving Hasbrouck’s message Clarke stepped out and tested the ground. He could not believe it. The ground was frozen solid. Shortly thereafter, Hasbrouck called and asked, “Bruce, do you think you can get out?” Clarke answered, “A miracle has happened, General! That cold snap that hit us has frozen the roads. I think we can make it now. At 0600 I’m going to start to move.”

General Hoge received his order to pull CCB, 9th Armored out at 0605 on December 23. The formations started to peel backward in succession from opposite Neubruck to Maldingen. As each unit joined the rear of the column, it took its turn being the rear guard. Company A of the 14th Tank Battalion had some trouble disengaging. Two of its tanks were mired in mud that had not frozen and had to be retrieved by a tank dozer. Then, four German antitank guns covering the Grufflingen-Maldange road were encountered. One gun, firing from the house that had been the 14th Tank’s command post an hour earlier, disabled two of the Shermans, but the other tanks managed to knock out the four antitank guns plus three German command vehicles.

Ninth Armored and its attachments traveled southwest on N26 to the junction with N33 west of Beho, then turned north on N33 to Salmchateau, and finally west on N183 through Lierneux to Malempre-Jevigne, southeast of Manhay. The tanks of the 14th Tank Battalion and the half-tracks of the 27th AIB paused to pick up the foot elements of the 424th RCT, 106th Infantry Division. Company C, 27th AIB withdrew under heavy artillery and sniper fire but managed to destroy a number of German vehicles.

The last of the St. Vith defenders to come out were Task Force Jones and the 112th Infantry Regiment. These troops were hit by the Führer Escort Brigade and driven from Rogery to Cierreux in some disarray. Fortunately, a tank destroyer from Vielsalm turned up and hit the leading two German panzers, which drove the rest for cover. Task Force Jones and the 112th Infantry eventually found their way into 82nd Airborne Division lines during the night of the 24th, but not before the units suffered heavy losses.

The losses in men and equipment for CCB, 9th Armored, as with the rest of the American units defending St. Vith, had been severe. The line companies were down to one officer apiece. Staff officers were casualties. A platoon of tank destroyers had vanished. The hardest hit, though, were the armored infantrymen of the 27th AIB with nearly 300 battle casualties. Ten tanks, numerous supply vehicles, armored cars, and jeeps were lost to enemy action.

Ninth Armored sent out billeting parties as it reached its new area. A two-day rest was planned for everyone. This break appeared to be only a dream, however, as it seemed every outfit wanted a piece of CCB, 9th Armored to help shore up its positions. The new sector assigned to CCB was on the fringe of territory the Sixth Panzer Army had mapped out for its further maneuvers. General Lucht’s 66th Corps was shifted from General Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army to the Sixth Panzer. The 27th AIB was ordered to establish a defensive position south, east, west, and southeast of Malempre. Roadblocks were set up and manned. Mines were laid. By 2300 enemy patrols tested 27th AIB’s new position and a night attack was thrown back with the help of D Troop, 89th Recon.

The heroic defense of St. Vith, though costly in men and materiél, disrupted the German timetable extensively. Rather than reaching the Meuse and driving on to Antwerp, the offensive stalled and eventually was turned back. The stubborn defenders of St. Vith played a major role in defeating the final German offensive of World War II in Western Europe.

First-time contributor Charles Gutierrez is the son of a 9th Armored Division veteran. The Pontiac, Michigan, resident also served 10 years in the U.S. Army.

It is interesting to note that the U.S 7th Armored Division suffered a moderate 425 Battle Casualties, on page 465 of “Hitler”s Last Gamble” by Trevor N. Dupuy, for December 17-23, 1944 in the Battle of Saint Vith including the 1st day of the Battle of Manhay, out of the 3,397 Battle and Non-Battle Casualties suffered during the Battle by the U.S 112th Infantry Regiment of the U.S 28th Infantry Division, the U.S 424th Infantry Regiment of the U.S 106th Infantry Division, Combat Command B of the U.S 9th Armored Division and ofcourse the U.S 14th Cavalry Group. Daniel P. Kneeland, Grafton, Ma.

What many don’t know is that Troop D, 89th Recon, was made up of former horse cavalrymen from 2d Cavalry Regiment before the regiment was mechanized and had been guarding the Mexican border on horseback following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, fearing a Japanese invasion through Mexico.

Does anyone know of any documentation of the Weather units (especially Div RR) during the Battle of the Bulge? My Dad was a U.S. Army Air Corps weatherman during that time. He spoke very little of his war experience ; I would really like to know more about what his work entailed.