by Michael D. Hull

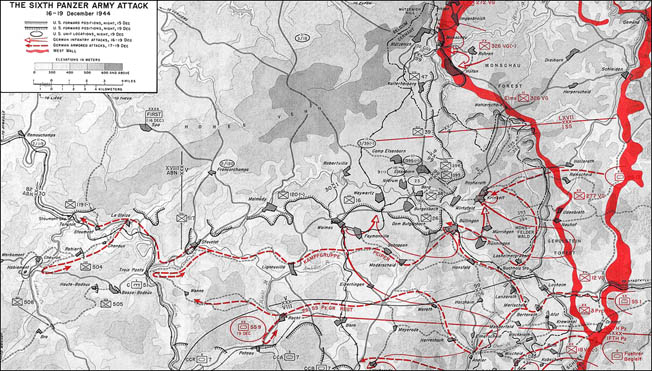

When Adolf Hitler’s last major World War II offensive burst through the chill Ardennes Forest early on December 16, 1944, it scattered American frontline units and caused many anxious hours in the Allied high command.

[text_ad]

How could three great panzer armies, marshaled in tight secrecy in the Schnee Eifel, trigger such chaos and initial inertia after senior Allied field commanders had been assured by their intelligence chiefs that the Germans were no longer capable of mounting a large-scale attack? Signs of an enemy buildup had been disregarded, and the victory euphoria that had gripped the Allied armies as they pushed toward the Siegfried Line and the Rhine River was rudely shattered.

Initial Setbacks & Spotty Resistance

Although the British, American, and Canadian leaders did not know it at the time, the enemy threat to split their armies and seize the strategic port of Antwerp was based on a shaky premise concocted by the unbalanced Nazi führer. And his offensive was not about to alter the course of the war. It swiftly fell behind schedule because of spotty but staunch U.S. resistance and logistical setbacks.

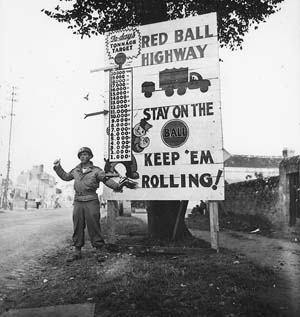

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt’s panzer, artillery, and infantry formations started out with only enough fuel for six days’ operations, and Hitler had said they would have to rely on capturing Allied dumps during their push westward. They failed because U.S. Transportation Corps truck drivers of the legendary Red Ball Express, most of them black soldiers, raced through Belgium to evacuate thousands of gallons of gasoline and oil from depots near Spa, Stavelot, and Malmedy that were in the path of the German thrust. Quick-thinking Belgians also helped to ensure that fuel did not fall into enemy hands.

The Gasoline Shortages That Crippled German Offensive

Gasoline shortages crimped German operations everywhere in the Bulge, attributable partly to the failure to capture American stockpiles and also to lengthy traffic jams on steep, twisting, icy roads behind the lines in the Eifel. General Josef “Sepp” Dietrich’s panzers used up their fuel battering against Elsenborn Ridge for two days, a lack of gasoline abruptly halted the 2nd SS Panzer Division once it had crossed the Ourthe River, and as early as December 19, all of General Hasso von Manteuffel’s tank units were crying for fuel. The 1,500 tanks Hitler had committed to the counteroffensive could not go far.

The enemy’s lack of gasoline and diesel fuel led to transportation deficiencies, which, in turn, resulted in ammunition shortages and more failures all the way down the logistical line. Relentless British and American bombing raids had paralyzed the German transportation system, raw material deliveries had sagged, and the production of tanks, guns, shells, and all types of weapons had subsequently tumbled.

The German Army was running out of serviceable trucks, and production could not make up for those destroyed in the Bulge. Also, the Wehrmacht was still heavily dependent on horse-drawn transport. Some enemy formations in the Ardennes in late 1944 had more horses than German infantry divisions in 1918. Horse-drawn artillery and supply columns got tangled up with the motorized transport during the first days of Rundstedt’s offensive, and this retarded the distribution of needed materiel to forward units. The German counteroffensive ultimately failed because neither Hitler nor his army high command fully understood the importance of supply and its effective organization. This was something the U.S. Army did understand.

Hunkering Down To Wait for Deliveries

While the Americans were in control of their logistical situation during the Battle of the Bulge, they were not without problems. Denied the use of English Channel ports, the Allied supply lines were strung out 500 miles from the Normandy supply dumps. Rolling around the clock, often at reckless speed, between August 25 and November 16, 1944, thousands of two-and-a-half-ton trucks of the Red Ball Express hauled 412,193 tons of critical supplies to the advancing armies.

Nevertheless, not enough materiel was reaching the front, and the shortage of gasoline worsened, with Allied tank squadrons forced to halt, hunker down, and wait impatiently for deliveries. General George S. Patton Jr.’s hard-driving Third Army was brought to a halt because of the fuel shortage, and he was not amused. On one occasion, when a ration convoy arrived, Patton raged to General Omar Bradley, commander of the 12th Army Group, that he would “shoot the next man who brings me food. Give us gasoline; we can eat our belts.”

The other dilemma facing the U.S. Army when the Germans broke through on December 16 was a direct result of General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s controversial broad-front strategy. He had no theater reserve to commit to the battle. The only two units available were the veteran but lightly armed 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions, both still refitting near Reims, France, after their battering in the ill-fated Operation Market Garden that September.

Dazed Indecision At Allied Headquarters

Dazed indecision infected Ike’s headquarters, and inertia gripped General Bradley. “Pardon my French,” he muttered, “but where in hell has this son of a bitch gotten all his strength?” Some senior officers believed that the breakthrough was just a spoiling attack. But General Eisenhower rose to the occasion and alerted the two airborne divisions for urgent deployment to the Ardennes as a stopgap measure.

Red Ball trucks and semi-trailers were swiftly warmed up, and the paratroopers were rushed into action on December 17-18,—the 82nd Airborne to the Werbomont area on the northern flank of the Bulge and the 101st Airborne to Bastogne, a critical road junction, to join an element of the 10th Armored Division, just as the Germans were closing in. The strategic town was soon under siege.

Patton’s Brilliant Tactical Maneuver

Meanwhile, at Eisenhower’s request, General George S. Patton directed three of his divisions in eastern France to make a 90-degree turn and highball north, stem the enemy advance, and relieve the “Screaming Eagles” at Bastogne. Despite logistical nightmares, bitter weather, and icy roads, an entire corps, about 60,000 men, was moved to the left flank of the Bulge that stretched from Echternach in Luxembourg to Bastogne. It was one of the most brilliant maneuvers of World War II.

Patton, whose sound staff work was generally underrated, had devised three plans to meet any contingency. The swift response that helped to turn the tide in the Bulge was probably the finest hour in his distinguished career.

As exemplified by the Third Army’s performance, nowhere during the war was the American mastery of logistics more dramatically displayed than in the Battle of the Bulge. General Bradley later observed, “He [Hitler] had forgotten that this time he was opposed not by static troops in a Maginot Line, but by a vast mechanized U.S. Army fully mounted on wheels. In accepting the risk of enemy penetration into the Ardennes, we had counted heavily on the speed with which we could fling this mechanized strength against his flanks.”

Originally Published December 2, 2014

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments