During the Battle of the Bulge, Adolf Hitler launched his last great counteroffensive along the Western Front. From full armored divisions running on gasoline fumes to “American schools” teaching spies how to pose as Allied soldiers, Hitler used everything in his arsenal to try to turn the tide of the war. Here are just a few of our stories on this historic battle.

Taking Down A German Fighter By Hand

Private Harry Cruse was sitting in the passenger seat of his Dodge cargo truck, manning a .50 caliber machine gun mounted on a ring turret when the plane roared up behind him at tree-top level. He quickly aimed and pushed the butterfly trigger. A stream of red tracers shot into the sky and punctured the plane’s fuselage. “I probably hit the pilot,” Cruse recalled years later.

There was no fire, but the plane nosed down and exploded on impact less than a mile away. Cruse and some of the men drove out to see his quarry. One soldier cut some of the material off the plane as a souvenir, but no one disturbed the dead Luftwaffe pilot. “He was all clean shaven and well dressed,” said Cruse. Part of the back of the pilot’s head was missing.

Battle Tanks in the Ardennes Forest

The most powerful tank of World War II, a single 67-ton Tiger II could hold up a dozen Sherman tanks, and often did. Known variously as the Tiger B, King Tiger, and Royal Tiger, the Tiger II carried a crew of five, had a 600-horsepower engine and a maximum speed of 21.74 miles an hour, and boasted a cruising range of 105.57 miles.

It could knock out with ease any Allied tank at considerable range, and its armor was so thick (1.58 inches to 7.09 inches) that few British or American weapons could destroy it. Fortunately for the Allies, production of the Tiger II behemoths was constantly disrupted by Anglo-American bombing raids and shortages of raw materials, so only 489 of them had entered service by the time the war ended.

Retrieving Artifacts from the Lausell crossroads

…He pulled a rusty American helmet from the ground. It had been an easy target for his metal detector, and the artifact proved something special. It had a hand-painted Indian head insignia—emblem of the 2nd Infantry Division.

The helmet actually had two such insignias, one on its steel shell and the other on its plastic liner. The latter also had a crudely etched rank insignia of a Technician Fifth Grade; Jean-Louis Seel had never found a helmet like it before in more than a decade of searching for battlefield relics. Best of all, the helmet came from Lausdell. Seel knew well the story of McKinley’s battalion and its defense of the crossroads.

How Colonel Creighton Abrams Made Battlefield History

On the chilly afternoon of Tuesday, December 26, 1944, a column of mud-caked Sherman tanks, halftracks, scout cars, and tank destroyers of the U.S. 37th Tank Battalion was drawn up on a roadside in southeastern Belgium. It was ten days into the Battle of the Bulge.

On that December 26, 1944, Abrams was down to 20 tanks, enough for one more assault. Should he take a chance and ask for permission to head straight for Bastogne, regardless of the strength of enemy opposition? Just then, waves of Douglas C-47 transports roared overhead and started parachuting supplies into Bastogne. Abrams’s mind was made up, and he dashed back to his Sherman, nicknamed “Thunderbolt IV,” and radioed Major General Hugh Gaffey, commander of the 4th Armored Division, for permission to move ahead. The word came a few minutes after 3 p.m.

Impassive, but with his eyes glinting, Abrams stuck a large cigar in his mouth, clambered into the turret of his tank, and radioed to his men, “We’re going in to those people now. Let ‘er roll!”

Avenging St. Vith

The 7th Armored Division fought a running battle out of St. Vith on December 23, 1944. After the destruction of the 106th Infantry Division in the first days of the Battle of the Bulge, the 7th tried to hold, but could not withstand the pressure of six German divisions bearing down on it. Unlike the 106th however, the 7th withdrew without major losses, and in good order.

In late January, with the German offensive stopped cold, The U.S. Army’s XVIII Corps was ready for revenge. General Matthew Ridgeway, the corps commander, General Robert Hasbrouck, commander of the 7th, and Brig. Gen. Bruce Clark, commander of the 7th’s Combat Command B, who had defended St. Vith and led the final retreat away from the town, all wanted it back. On January 22, after a major fight during a snowstorm at the town of Hunnage, the road to St. Vith was open. The next morning Hasbrouck called Clark and said, “You got kicked out of St. Vith. Would you like to take it back?” Clark immediately agreed and set off to organize his troops.

Mysterious Messages That Should Have Tipped Off The Allies

“On the night of July 21 my squadron had a weird experience. The usual German night intruders were overhead trying to drop their mines to interfere with our unloading operations at Omaha Beach, and our usual antiaircraft “Fourth of July” show was in full visual and sonic bloom when suddenly, Corporal Albert Gruber, monitoring his Hallicrafter intercept set, heard a panic-stricken German pilot announce, “I’ve been hit—am losing altitude—must get rid of my load.” Before Gruber had finished writing this down on his message pad he saw a blinding flash in the field adjoining his and seconds later a blast wave knocked him off his chair.”

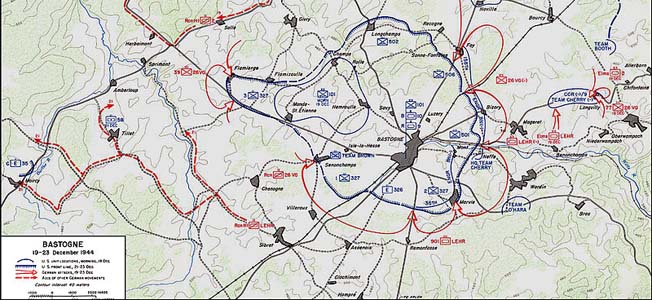

The Roads to Bastogne

“An eternal grayness created a sense of constant gloom. The short, wintry days ended quickly, giving way to endless hours of dark, monotonous cold, and ever-present clouds of ghostlike fog crept slowly over the landscape, blocking all sight. To make matters worse, the swirling winds carried sounds from every direction that bedeviled the inexperienced soldiers with visions of skulking German sharpshooters and the steady, low rumble of enemy armor on the move.”

Why Did Hitler Choose Belgium?

Belgium may have been an ideal place to hide a huge offensive, but the land did not favor such action once it began. Despite the superiority of Tiger and Panther tanks and the experience of the German Army, the numerous streams and hilly ground gave the Americans excellent defensive positions from which to slow the attack.

In the end, the advantages of Belgium could not outweigh the disadvantages. A sustained offensive on such terrain could not be given the demands of a two-front war. The German plan at the Battle of the Bulge, while excellent for providing a breakthrough, could not achieve a breakout.

Touring the Battleground Today

The Battle of the Bulge lasted an entire month, and was fought over almost the entire Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and half of Belgium, yet finding all of the battlefields and historic sights is a bit more difficult than locating the D-day beaches. While there are plaques, statues, and a few museums dedicated to the campaign, they are all privately funded and are not complementary of one another in the way they might be under a national park-type system.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments