By Patrick J. Chaisson

As a late summer sun finally dipped below the horizon, Captain William L. Koob, Jr., came to realize that his unit had been abandoned on the battlefield. The infantrymen assigned to help defend Koob’s 57mm antitank guns against German infiltrators were no longer in position, leaving his lightly-armed cannoneers to fend for themselves.

Worse still, all communication links with higher headquarters had been severed. Captain Koob, commanding Antitank Company, 317th Infantry Regiment, 80th Infantry Division, could not request reinforcements or learn what was going on. He and his men were, quite literally, alone in the dark.

Koob dispatched several contact patrols, but these detachments all failed to locate friendly troops. The 24-year-old captain even went out himself in search of help, but after walking 400 yards in this unfamiliar but definitely hostile terrain he “suddenly felt extremely naked” and returned to the relative safety of the Antitank Company’s perimeter.

Unbeknownst to Captain Koob, thousands of soldiers were in motion all around his lonely outpost that night. Some men, wearing the U.S. 80th Infantry Division’s “Blue Ridge” shoulder patch, advanced warily toward high ground that dominated the surrounding countryside. Other combatants, clothed in German Army, Air Force, or Waffen-SS uniforms, set off in a desperate attempt to escape the massive Allied trap that was rapidly closing around them.

These adversaries would collide with one another along a roadway north of Argentan, France, shortly after dawn on August 20, 1944. The chaotic melee that followed led to a decisive win for the 80th Infantry Division, then fighting its first major action of World War II.

Yet the men of the Blue Ridge Division paid a steep price for their battlefield victory. Enlisted soldiers quickly discovered that no amount of training could fully prepare them for the terrifying realities of combat. Officers learned hard lessons too, as their failure to properly utilize armor, artillery, and engineer bridging assets caused many unnecessary casualties.

Infantry leaders repeatedly ordered riflemen forward in a series of futile assaults, only to have them mowed down by dug-in German tanks and machine guns. Furthermore, these officers stubbornly refused to consider other schemes of maneuver better suited to the terrain and enemy laydown. The situation required a confident, self-assured division commander to take charge; that man, however, was also struggling to learn his job.

Major General Horace L. McBride served as the 80th’s commanding general during its bloody baptism by fire at Argentan, and throughout the war in Europe. A 1916 graduate of West Point, McBride first saw action as an artilleryman in World War I. His interwar career included assignments to Panama and the Philippines, as well as instructor duty at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He assumed command of the Blue Ridge in March 1943, taking his outfit overseas the following summer.

McBride’s division crossed the English Channel into Normandy during the first week of August 1944. Now under the command of XII Corps, Third U.S. Army, the unit spent several days in a forward assembly area, preparing itself for battle.

The 80th consisted of approximately 14,600 soldiers. Its primary maneuver force, three infantry regiments numbered the 317th, 318th, and 319th, was supported by four field artillery battalions (FABs). The 314th, 315th, and 905th FABs all employed 105mm towed howitzers, while the 313th FAB fielded larger 155mm cannon. The 305th Engineer Combat Battalion and 305th Medical Battalion, along with several smaller signal, cavalry, and service support formations, rounded out the division’s wartime organization.

While in bivouac, McBride’s outfit was joined by the 702nd Tank Battalion (TB), 633rd Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion, and 610th Tank Destroyer (TD) Battalion. These attachments were made to increase the division’s lethality, especially against German aircraft and armored fighting vehicles.

The Blue Ridge next reconfigured itself into three combat teams, each centered on an infantry regiment. Combat Team (CT) 317 included the 317th Infantry Regiment and its 3,000 riflemen, the 315th Field Artillery Battalion (FAB), as well as a company each of tanks, engineers, medical aidmen, and TDs. Built around the 318th Infantry Regiment, CT 318 employed the 314th FAB together with armor, TD, and combat support elements. The 905th FAB (105mm towed) provided artillery support for CT 319, while the 313th FAB’s powerful 155mm howitzers remained under division control.

On August 7, McBride’s command was reassigned to XX Corps along with orders directing it to occupy the city of Le Mans. This change of mission came in response to a surprise German counterattack that struck U.S. formations well to the west at Mortain. The 80th Division was needed immediately to help shore up a suddenly vulnerable segment of the front line.

August 8 saw the Blue Ridge Division conduct a 40-mile motor march to the outskirts of Le Mans. It also received assignment to XV Corps, thus beginning a dizzying series of transfer orders that would shift control of McBride’s unit almost daily between the four corps comprising Third Army. It was a necessary but confusing means of coping with the extraordinarily fluid situation that confronted Allied commanders in Normandy during early August 1944.

This was a time of great opportunity for Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, commanding all Allied land forces in France. During the eight weeks following D-Day, his British-led armies in the north captured the city of Caen while simultaneously crushing their foe’s most capable combat formations (albeit at great cost to themselves in men and equipment). Meanwhile, G.I.s under Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley finally broke out of Normandy’s bocage region and began a wide, sweeping thrust to the south and east.

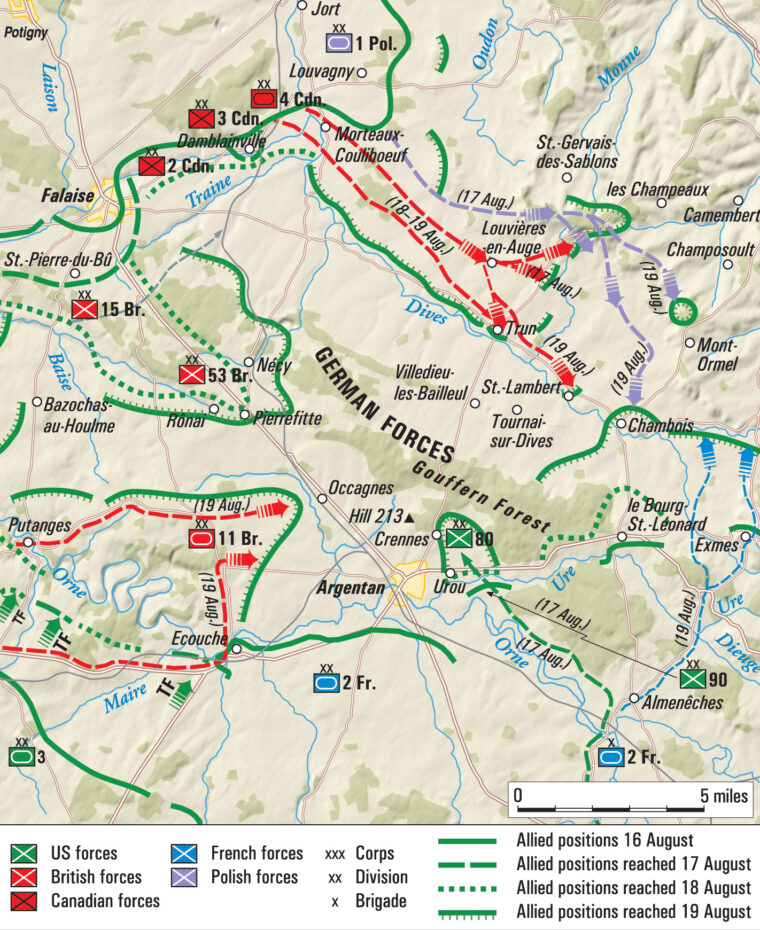

Leading the charge across France was Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s Third U.S. Army. Operational only since August 1, Third Army already had a full list of missions to accomplish. One element (VIII Corps) turned south to capture several port cities along the Brittany peninsula. Patton’s other three corps (XII, XV, and XX Corps) moved east, paralleling the British frontline trace to their north. This maneuver was meant to create a “pocket,” inside which would be trapped the German Fifth Panzer and Seventh Armies.

Montgomery and his American subordinates disagreed on how best to defeat these crippled but still dangerous adversaries. Bradley and Patton wanted to “go long,” advancing well eastward to cut their foes off from all escape routes across the Seine River. Monty preferred a safer option, sending forward British, Canadian, and Polish outfits then at Falaise south toward Argentan in a pincers maneuver designed to encircle most (but not all) of the German combat formations still fighting in Normandy. Relentless pressure applied by ground and air units within this so-called “Falaise Gap,” insisted the field marshal, would result in complete victory with less attendant risk to Allied troops.

Montgomery’s plan won out, much to the disgust of Generals Bradley and Patton. Orders issued on August 11 formally assigned the capture of Argentan to General Harry Crerar’s First Canadian Army. This obliged Third U.S. Army, its lead elements already marching on the city, to cancel all attack plans.

Frustrated, Patton sought to maintain the initiative by sliding elements of his XV Corps eastward toward the Seine bridges starting on August 13. While Bradley authorized the maneuver, he did express concern about a 25-mile hole in the lines that had developed between Patton’s thinly-spread XV Corps near Argentan and other American commands to the west. This breach needed to be sealed, and the force ordered to do so would include Maj. Gen. Horace McBride’s Blue Ridge Boys.

At 0400 hours on August 13, CT 317, CT 318, and division troops started off on a tactical road march toward Argentan. Combat Team 319 stayed behind in Le Mans, however, as it had been detached for outpost duty. This command would not rejoin its parent division until after the battle of Argentan concluded.

On August 15, McBride reported that his outfit had closed on its assembly areas as of 0700 hours and stood ready to act as Third Army’s reserve. Meanwhile, Patton – under pressure from Bradley to plug that hole in his battle zone – created a Provisional Corps comprised of the 80th and 90th Infantry Divisions, as well as the 2nd French Armored Division, with orders to firm up the Americans’ shoulder near Argentan.

It so happened that on August 16, Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow’s V Corps headquarters, a First Army organization, had become available for assignment. General Bradley, unaware of Patton’s plans, directed Gerow to take charge of those three divisions comprising Third Army’s Provisional Corps and continue the advance. That same day, Montgomery called down to Bradley’s HQ and suggested a new linkup point be established between Crerar’s men and the Americans. This meant Argentan once again fell within the U.S. area of operations.

Gerow, however, needed time to relocate his command post, orient himself to the situation, and issue a proper operations order. Furthermore, the 13 battalions comprising V Corps Artillery had to move into and establish firing positions within their new zone. To allow for these necessary measures to occur, V Corps postponed all coordinated attacks until August 18.

On V Corps’ right flank, the 90th Division would take and hold Chambois, newly-designated as the meet-up point between British and American forces. To the left, French tankers of the 2nd Armored Division were to establish a strong position near Ecouche and prevent German troops from breaking out of the Allies’ trap in that direction.

In the center, McBride’s division would advance in a northerly direction, keeping east of Argentan, to seize high ground overlooking the city. This maneuver was intended to cut off Argentan’s garrison and compel it to either evacuate or surrender, permitting the Blue Ridge Boys to dash in without resorting to a costly frontal assault. Three battalions from V Corps Artillery were to serve as general support for the 80th’s attack, which was now set to kick off after dawn on August 18.

Defending Argentan and its approaches was a scratch force of foot soldiers, tankers, Luftwaffe anti-aircraft gunners, paratroops, and Waffen SS men. Hastily cobbled together from the remnants of several once-proud formations, this ad-hoc kampfgruppe (task force) served as a rear guard for SS Oberst Gruppenführer (General) Paul Hausser’s rapidly retreating Seventh Army.

American commanders believed an estimated 2,000-2,500 German soldiers and 35 PzKpfw. V Panther tanks occupied the Argentan sector. These men mostly belonged to the 9th and 116th Panzer Divisions, fighting alongside a number of Luftwaffe flak crews. Battle-wise and determined to avoid capture, they were, as an 80th Division intelligence analyst described, “…well dug in in the finest defensive positions, protected by tanks, artillery, anti-aircraft guns, automatic weapons, barbed wire entanglements, and well-placed mine fields.”

“The terrain was also tough,” another Blue Ridge Division officer wrote, “favoring the enemy in defense with its hedgerows and sufficient open spaces to permit good fields of fire for tanks, and mutually supporting automatic weapons. In addition to this, the enemy had cleverly zeroed in every key avenue of approach to his positions for accurate artillery fire.”

Weather conditions were typical for Normandy in late August. The daytime high temperature averaged 71 degrees, while nighttime lows dropped into the mid-50s. Intermittent thundershowers gave way to partly cloudy skies after sunrise on August 18; the rain would not return for two days. This left most roads muddy but trafficable by tactical vehicles.

Acknowledging his soldiers’ near total lack of combat experience, Maj. Gen. McBride devised as straightforward an assault plan as possible. A narrow axis of advance permitted the passage of only one infantry regiment at a time, which suited McBride since he had only one combat team (CT 318, commanded by Colonel Harry D. McHugh) available for use. Colonel A. Donald Cameron’s CT 317 could not be employed, as Maj. Gen. Gerow had previously designated it as V Corps Reserve.

The infantrymen of CT 318 were to jump off from attack positions near the hamlet of Urou, moving in a northerly direction to cross their line of departure (the main road running east-west from Argentan to Le Bourg-St. Leonard) not later than 0800 hours on August 18. The G.I.s’ final objective, a prominence known as Hill 213, sat about 3.3 miles from their start point. From this hilltop, situated on the edge of the Gouffern Forest, they could then look down into Argentan and take that city if the opportunity presented itself.

First Battalion, led by Lt. Col. Gustof A. Lindell, would go in first, followed closely by Lt. Col. John C. Golden’s 2nd Battalion. Third Battalion (Lt. Col. John B. Snowden II, commanding) remained in reserve. The G.I.s were to maneuver in a tactical formation known as “column of battalions.” which allowed for rapid movement and ease of control but made them vulnerable to flanking fires.

First, though, CT 318’s riflemen had to reach the battlefield. An unexpected swampy area hindered their approach, while supporting tactical vehicles were held up by a “natural anti-tank ditch” known as the Ure River. Failure to conduct proper reconnaissance prevented U.S. armor from lending its weight to the fight until combat engineers could find a fording site, a process that took most of the morning.

Following a one-hour artillery preparation, the Blue Ridge Boys commenced their assault. Sometime between 0730 and 0800 hours, Lindell’s 1st Battalion crossed the main highway north of Urou and turned east, heading for a fortified farmhouse complex. There, in the words of an 80th Division historian, “…very heavy fighting was encountered.” By 0905 hours, however, this strongpoint had been reduced and the G.I.s began their movement north toward Hill 213.

Yet after covering a few hundred yards Lindell’s men came scurrying back, forced to seek cover by ferocious tank, artillery, and small-arms fire. Well-sited German defenders, firing from strong positions on the outskirts of Argentan, quickly unhinged 1st Battalion’s attack. Those gunners then turned their wrath on 2nd Battalion, caught on the flank while still in column formation.

Lieutenant Colonel Daniel J. Minahan, an artillery battalion commander, witnessed this slaughter. “While heading to the front,” he wrote, “I came across elements of the 2nd Battalion 318th near the village of Urou. They had tried to cross the road in order to achieve their objective. Losses were heavy, inflicted by enemy machine guns and 40mm mobile antiaircraft cannons whose position nobody had been able to fix.”

Second Battalion’s plight worried Maj. Gen. McBride, who was observing the day’s action from CT 318’s command post (CP). Desperate to destroy the hidden German guns then wreaking havoc on his men, McBride ordered a platoon of supporting M4 Sherman tanks to push forward and seize an enemy-occupied hedgerow. Five M4s, led by 2nd Lt. William B. Miller, set off on this assignment at around 1000 hours.

Within minutes, four of Miller’s Shermans were destroyed by unseen 75mm antitank guns. Corporal Jack Weaver, a gunner in the fifth vehicle, described what happened: “We started to turn to the road on the left and follow the other tanks. Through my periscope I saw flashes of fire, huge clouds of black billowing smoke, and guys I knew jumping from burning tanks. The 3rd Platoon was wiped out, except for us.”

One tanker perished in this brief encounter, while two more were listed as missing in action and 10 men wounded. Weaver later remembered seeing “a hole left by a German armor-piercing shell” in the center of each white recognition star painted on the Shermans’ hulls. Miller believed enemy gunners tracked his M4s by watching for the identification pennants attached to their tall radio antennas. It was a sudden and shocking introduction to combat for the men of the 702nd Tank Battalion.

Vicious German automatic weapons and artillery fire had stopped CT 318’s assault cold just yards from its jump-off point. Worse, these G.I.s were now under direct enemy observation where even the slightest movement could provoke a violent response. That afternoon, Lt. Col. Lindell and Major Robert B. Norris were issuing orders from behind a haystack when enemy shells struck and killed both men.

At 1700 hours, 3rd Battalion passed through the remnants of 1st Battalion and entered the fray. Its commanding officer, Lt. Col. John Snowden, recalled what happened next: “At the moment when we began the attack, K Company was on the left and L Company on the right. We had crossed a road and ahead of us lay an immense field of clover that sloped down for 500 yards and then rose up again for another 500 yards toward the edge of the forest. When our troops launched their assault toward the edge, the Germans opened fire with everything they had: mortars, artillery, machine guns and rifles. We were totally exposed, with almost no place to hide.”

After nightfall, both sides paused to lick their wounds. As litter-bearers carried off the wounded, Maj. Gen. McBride made his way back to the 80th Division CP near Almeneches. There, he and his staff began work to better synchronize all the elements of combat power at their disposal when fighting resumed at sunrise.

This meant employing field artillery, seven battalions of it, against known and suspected German positions around Argentan. From 0400 to 0600 hours on August 19, over 80 105mm and 155mm guns pounded away in an attempt to “soften up” the objective. Then, at 0645 hours, the infantry went forward.

Second Battalion tried once more to take the main highway east of town. Its advance was again met with “a withering fire,” according to the Blue Ridge Division’s historian. No gains were made that day despite the valor of soldiers like Company F’s Pfc. Thomas E. DiMartino, who received a Bronze Star for directing artillery on a German 20mm position while wounded and in an unprotected position.

Meanwhile, 3rd Battalion’s attempt to continue moving forward also encountered fierce opposition. By 1430 hours, the Americans’ assault had ground to a halt with little to show aside from a long list of casualties. General McBride reluctantly canceled CT 318’s attack orders and had that outfit transition into a defensive posture so it could consolidate and reorganize.

By now, CT 317 was available for duty after having been released from Corps Reserve the night before. A new unit brought fresh perspectives: unit commanders saw a way to slip their troops around the 318th’s right flank through a grove of trees that concealed them from enemy observation. The maneuver worked — sometime between 1600 and 1755 hours (accounts differ) the 317th’s riflemen started moving northward “despite terrific enemy infantry, artillery, and armored resistance,” as one account described it.

Not all the shellfire directed against CT 317 was German, however. After a volley of “short rounds” fell on the infantrymen of Company F, a medic named Pfc. Hoyt T. Rowell dashed across an open field to signal some attached forward observers that they needed to shift their aim. He then returned to treat those men wounded by this errant artillery, an act that earned him the Blue Ridge Division’s first Distinguished Service Cross for valor in World War II.

Throughout August 19, U.S. forces struggled to keep up the pressure on their tenacious opponents. Thousands of soldiers and their tactical vehicles had by this time churned all crossing sites along the Ure River into a nearly-impassible quagmire, slowing the arrival of badly needed tanks and guns.

Some of those heavy weapons belonged to Lt. Col. William L. Herold’s 610th TD Battalion. At about 2030 hours, Herold and several members of his command group were working to speed traffic over the Ure when a volley of high-explosive projectiles landed among them. Severely wounded, Herold was evacuated to a clearing station where he died at 0130 hours the next morning.

In the meantime, lead elements of CT 317 had moved northward almost two miles to form a battle line along the Argentan-Crennes road. Most of these troops belonged to the 2nd Battalion, 317th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lt. Col. Russell E. Murray. As darkness began to fall, Murray’s men were joined by a number of cannoneers under Captain Koob of the 317th’s Antitank (AT) Company.

Koob controlled a powerful force. In addition to the dozen 57mm cannons comprising AT Company, he had attached to his command 12 towed 3-inch guns belonging to the 610th TD Battalion as well as eight tracked M-10 tank destroyers from the 893rd TD Battalion. Leaving the towed pieces back to cover key road junctions, he deployed his M-10s and 57mms well forward in an orchard near the hamlet of Crennes.

After sundown, Koob noticed the riflemen detailed to guard his perimeter had all vanished. Only later did he learn that Murray’s battalion had been called away (without anyone informing him) so it could conduct a night attack on Hill 213. American tactical doctrine normally discouraged such maneuvers, though, as they were difficult to synchronize and fraught with the risk of friendly fire.

General McBride, the man who ordered this assault, recognized these dangers but gambled on a night fight to help regain the initiative. His chief of staff, Colonel Max S. Johnson, set out around midnight to coordinate details with Colonel Cameron of CT 317. Curiously, Cameron could not be found anywhere, so Johnson then went on to Lt. Col. Murray’s CP bearing instructions for an immediate advance.

Beginning at 0100 hours on August 20, Murray and his men cautiously made their way up about 1,000 yards to the Argentan-Trun Road. Company E, on the right, split off to occupy Hill 213. Yet these soldiers were deep in enemy territory, without reinforcement, and still unable to contact Colonel Cameron’s HQ.

That night, the Germans defending Argentan started to evacuate. Harried by incessant American artillery barrages, a column of tactical vehicles including Panther tanks, halftracks, command cars, and trucks departed the city around 0430 hours heading up the road to Trun. Their route took them directly past Lt. Col. Murray’s “lost battalion,” now bolstered by additional infantrymen, Captain Koob’s AT guns, and a company of Sherman tanks.

As rain and fog blanketed the battlefield, weary G.I.s identified the sound of armored vehicles approaching from Argentan. First to pass through the kill zone was a motorcycle escort; Lieutenant Doug Cox of Company H opened the Americans’ ambush with one deadly shot from his carbine. Then the roadway erupted in a maelstrom of gunfire.

“Their tanks began pushing their vehicles out of the way so they could get to us,” remembered Company G’s Private Benjamin Alvarado. “One tank got as close as fifty feet ahead of us before we knocked his track off with a bazooka shell, making it immobile. They used the machine gun from their tanks and fired their [cannon] at us but couldn’t lower their barrel enough to hit us.”

Alvarado’s account continued: “Another German tank was coming. Our radioman called for help. Only one American tank was available. We could see him behind us. As the two tanks saw each other, their guns began to turn toward each other. With our tank still in motion, the German tank got the first shot off…. It ricocheted off our tank. While still on the move, our tank fired twice and made a direct hit!”

Closer into town, a platoon of gunners from Company A, 610th TD Battalion, observed five enemy armored vehicles also attempting to escape the trap. About to engage with their towed 3-inch pieces, these cannoneers were told to stop by Brig. Gen. Edmund W. Searby, 80th Division artillery commander, who stood nearby. Searby, fearing the tanks were British, changed his mind only when he saw black crosses painted on their turrets. Now free to fire, the AT crews quickly dispatched four of the five fleeing panzers.

Heavy fighting continued well into the morning as Lt. Col. Murray’s battalion continued its assault. Pfc. Earl G. Goins of Company E earned the Distinguished Service Cross when he sprinted through murderous enemy fire to singlehandedly destroy a machine gun that was pinning down his comrades. As friendly tanks, TDs and crew-served weapons finally reached Hill 213, Murray reported his objective secure at 1030 hours.

While elements of CT 317 finished mopping up to the north, its 3rd Battalion turned south to seize the ruined city of Argentan. That outfit was soon joined in town by Lt. Col. John Golden’s 2nd Battalion, 318th Infantry Regiment. At 1405 hours, the Yanks reported they had made contact with Tommies of the 11th Armoured Division advancing from Falaise. Combat Team 318’s Colonel McHugh declared Argentan secure at 1500 hours, holding a brief flag-raising ceremony alongside the city’s mayor shortly thereafter.

All across the 80th Division zone, disheartened enemy troops began to capitulate en masse. On Hill 213, Private Alvarado observed “a column of Germans, as far as you could see, with their hands on their heads, moving in our direction to surrender.” Officially, the division captured 1,009 prisoners during its three-day campaign at Argentan.

In addition, the Blue Ridge was credited with destroying 14 tanks and several dozen soft-skinned vehicles. On August 21, patrolling G.I.s discovered a munitions depot containing 27,000 tons of German war materiel. One warehouse, noted a logistics officer, was filled with 1940-dated maps of the United Kingdom. That same day, Maj. Gen. McBride formally turned over control of Argentan to the British 50th “Northumbrian” Infantry Division and moved his command into an impromptu rest area.

The 80th Infantry Division’s victory at Argentan came at great cost. Combat Team 318 suffered 416 casualties: 77 men killed, 303 wounded, and 36 missing in action. The human toll for CT 317 included nine soldiers killed and 45 wounded. The 305th Medical Battalion reported processing 432 casualties during the battle, while that organization’s Company B treated in one 24-hour period a total of 195 patients, all but three of whom required evacuation.

The Blue Ridge Boys went into battle at Argentan as untested novices, emerging three days later much wiser to the horrors of war. Combat, they learned, affected men in unique ways. “Some men were exhilarated (as I was),” said CT 317’s Major James H. Hayes. “Other men simply fell apart from fear; a few men became ‘shell-shocked’ or more euphemistically ‘battle fatigued.’”

Hayes also noted that several officers, unable to cope with the stress of battle, had to be relieved of duty. Indeed, the division’s senior leaders all struggled with their responsibilities to command effectively at Argentan. After trying and failing to press the attack using textbook tactics, Maj. Gen. McBride and his subordinates kept throwing men and machines forward without serious consideration of the situation or what they could do to change it.

The U.S. Army combined arms team that helped win World War II worked best when infantry, artillery, and armor all cooperated on the battlefield. This was not how the 80th Division fought during the battle of Argentan. McBride controlled a massive amount of field artillery, yet brought those powerful guns to bear almost too late in the fight to make a difference. He showed even less aptitude for mechanized warfare, recklessly sending Lieutenant Miller’s tank platoon forward only to be massacred by antitank gunners who were well prepared to defeat an unsupported armor assault.

Yet the Blue Ridge Division learned well from its costly baptism by fire at Argentan. Even as his men finished cleaning out the last pockets of resistance in their zone of operations, Maj. Gen. McBride started making plans to institute a rigorous training schedule for all three combat teams. His new syllabus would emphasize night fighting, tank-infantry operations, coordinated “time-on-target” procedures for artillerymen, and increased reliance on engineer support to speed the advance.

These tactical lessons, hard learned at Argentan, helped transform McBride’s unit into one of Patton’s most reliable fighting organizations. The 80th Infantry Division helped lead Third Army’s dash across France, then performed magnificently in a defensive role during the Battle of the Bulge. Horace McBride served as head of the Blue Ridge until V-E Day, distinguishing him as the only U.S. division commander in Europe who trained and fought with the same outfit throughout World War II.

Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired U.S. Army officer and historian based in Scotia, New York.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments