By Blaine Taylor

The year 1939 was one of massive military parades across Europe. On April 20, the largest ever was held in Berlin to celebrate Adolf Hitler’s birthday, complete with the paratroopers, wheeled artillery, tanks, half-tracks for motorized infantry, and overhead Luftwaffe fly-bys that would mark the coming campaigns and revolutionize warfare forever.

On May 1, Soviet dictator Josef Stalin held his own parade in Moscow’s Red Square for the Communist May Day celebration, while in June the Führer displayed his growing might once more to the visiting Yugoslavian regent, Prince Paul, his future ally. But it was the French martial march-past in Paris that garnered the lion’s share of attention in the world’s press, because it held out democracy’s best hope that the German dictator’s steady path of bloodless conquest might yet be stopped—either short of war or, if not, by it.

Thus, on Bastille Day, 1939—July 14—all eyes focused on the Champs Elysées in the shadow of the great Napoleon’s Arc de Triomphe as the might, main, and majesty of the colonial French Republican Empire paraded down the broad boulevard in the bright sunlight past delirious Parisians. In his memoirs, French statesman Georges Bonnet recalled that there were “Algerians, Moroccans, Senegalese and Indochinese, all those native regiments … which are testimony to the extent and Power of the French Empire.… Cannon of all calibers … tanks of all sizes … hammering the surface of the Champs-Elysées … squadrons, at high and low altitude, flying over Paris, from the Arc de Triomphe to the Obelisk … an impression of order, discipline, and irresistible force.”

Foes, Allies Impressed By French Military

Notes author Ernest R. May in his 2001 account, Strange Victory: Hitler’s Conquest of France: “This impression was shared by every foreign observer—every single one including officers from Germany and Italy and from Britain and other nations that would before long be France’s allies.” Indeed, among these were Stalin, who then considered the French Army the best on Earth, and Winston Churchill, who believed that his United Kingdom would be safe behind the strong shield and sharp sword of Gallic military strength. After all, hadn’t the same coalition of powers—plus the United States—defeated Imperial Germany in the Great War?

Indeed, the myth persists even to this day that the fall of France and her continental allies in a bare six weeks in 1940 was preordained, but that was simply not the case. Indeed, both the French and her Allied British generals and armies fully expected to win the war, as they had the last one.

Moreover, a myth persists that the French were dependent on horses for mobility while the Germans relied on mechanization, that the German tanks and planes were better and there were vastly more of them.

None of these things is true. Adds May, “Germany by most quantitative measurements was not nearly so well prepared for a major war as were France and Britain [with the full might of both their overseas empires and considerable navies behind them]. The Wehrmacht had many fewer vehicles and was much more reliant on horses. [German Chief of the General Staff General Franz] Halder estimated that each German infantry division needed 4,500 horses and 2,000 horse-drawn vehicles. The German Army was to commence war in September, 1939 with almost 600,000 horses and, in its Western offensive of May-June, 1940, was to be suffering a severe shortage of them.”

Continues May, “German equipment was generally inferior. French tanks were better gunned, better armored and more reliable. As many as half of Germany’s basic tanks, the Panzer Is and Panzer IIs, broke down simply propelling themselves across the level plains of Poland.”

Hilter’s Generals Warn Of Two-Front War

In fact, the Panzer IIIs and IVs, of which there were few, were the only tanks considered on par with those of the French and British. Hitler addressed these problems after the French campaign. In addition, in dogfights in the autumn of 1939, German fighters did so poorly against French fighters that German commanders ordered avoidance of one-to-one clashes.

On the other side of the Franco-German frontier, Hitler’s own generals knew all this only too well from their various intelligence services and their own war-gaming experience held each fall in Mecklenburg. They had seen firsthand the roadside breakdowns of the vaunted armored divisions of General Heinz Guderian in Austria, toured the surrendered French-designed Czech defensive bunkers that had fallen to them via the Munich Pact in 1938, and believed—correctly—that the military bombast of its ally Fascist Italy was a hollow shell (as was to be proven in both 1939 and 1940).

They did everything they could to persuade Hitler not to get Germany into a two-front war involving the Great Powers, a fight they believed heart and soul that they could not win. “Our generals in Berlin shit in their pants,” the Führer told his Minister of Propaganda Dr. Josef Goebbels after Munich.

Hitler Predicts Little Resistance From Allies On Poland

To give Hitler his due, if the defeats of 1943-1945 were his, so were the victories of 1936-1942, particularly those of that seminal year in modern warfare, 1940, on both a political and military level. As a practicing politician since 1919, he was correct in assessing that neither France nor Britain wanted another world war and would dither harmlessly while he overran Poland, which he did during September 1-27, 1939.

Notes May, “If Allied leaders had not believed France and Britain to be militarily at least a match for Germany, exasperation would not have sufficed to produce declarations of war on behalf of Poland.” In fact, and as May points out, it was their respective peoples and not the governments of the two Western Allies that demanded war with the Third Reich, so impressive had the Bastille Day Parade been on their collective psyches.

France and Great Britain declared war on Nazi Germany on September 3, but then did virtually nothing after that to effectively aid Poland. This was the first great mistake of what has come to be called the “Phony War,” or “Sitzkrieg” on the Western Front. While the blitzkrieg (Lightning War) crushed Poland, the armies of France should have invaded the German Saar and Rhineland regions, and the British Royal Air Force should have launched a full-scale air offensive against the Third Reich as later happened from 1942 on … but they did neither.

Secret Negotiations With The British

Believing they were safe behind the vaunted Maginot Line, the Allies left the striking initiative to Hitler—a fatal error. They constructed their joint strategy around a planned invasion of Germany in 1942, but Hitler struck them first. In addition, they had hoped—and not without justification—that a coup within the Reich itself might topple either Hitler alone or the entire Nazi regime on the thorny issue of the Great Power war.

On October 6, in a speech before the Reichstag, Hitler offered England a way out of the war that had been declared on behalf of a Poland that no longer existed. But First Lord of the British Admiralty Winston Churchill had already rejected that position five days earlier. He said, “Directions have been given by the government to prepare for a war of at least three years.… It was for Hitler to say when the war would begin, but it is not for him or his successors to say when it will end.”

What did Churchill mean by that last cryptic line? Behind the scenes—and either with or without Hitler’s approval—his number two Nazi and designated successor, Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring, had been secretly negotiating with the British through Swedish businessman Birger Dahlerus to stop the fighting. Göring even let it be known that he was prepared to do this if Hitler himself was overthrown.

Was this far-fetched? On November 9, a bomb exploded near the lectern of the Führer’s annual Beer Hall Putsch commemorative speech at Munich’s Burgerbraukellar. He had left early and narrowly missed death, but many of his Old Fighter supporters were killed or wounded. It is this writer’s position that Reichsführer (National Leader) SS Heinrich Himmler and his deputy, Reinhard Heydrich, either concocted or allowed this event to occur. Himmler hated the Nazi-Soviet Pact and wanted war with the Soviet Union, not the West. Neither Göring nor Goebbels wanted any war at all.

Hitler Angered About Reports Of Low Morale

On the 12th, Hitler met at the New German Reich Chancellery in Berlin with the Commander-in-Chief of the German Army, Col. Gen. Walther von Brauchitsch, whom he had appointed to office in February 1938. Now, his Army C-in-C informed him that there had been near-mutinous conditions in some German ground units over the planned winter offensive in the West, and that the general tenor of the infantry was not as good as it had been in the Kaiser’s Imperial Army of 1914-1918.

The Nazi Führer, who’d fought all during 1914-1918 as a foot soldier on the Western Front, flew into a fury, severely berating von Brauchitsch. What units was he talking about—and where? The Führer would fly there himself to address the troops—and their commanders’ heads would roll. Not for him another 1918, when the German Army had mutinied and the combined actions of the generals in the field and the republicans at home had overthrown Kaiser Wilhelm II!

Von Brauchitsch slunk back to Army Headquarters at Zossen, where he and Halder shelved their plans to overpower the Führer’s black-coated SS guards at the Reich Chancellery and arrest Hitler.

Meanwhile, the various German plans for Fall Gelb (Case Yellow) proceeded, designed for a winter offensive in the West. It would face 15 delays due to weather and not be launched until May 10, 1940 (when it actually had a better chance of success, as it turned out). Its crafting is a strange and interesting tale.

Many people would later attempt to grab credit for Case Yellow’s glorious vindication, not least of whom was the Führer. According to Albert Speer in his 1970 work Inside the Third Reich: Memoirs, “Hitler claimed total credit for the success of the campaign in the West. The plan for it came from him, he said. ‘I have again and again,’ he told us, ‘read Col. de Gaulle’s book on methods of modern warfare employing fully motorized units, and I have learned a great deal from it.’”

His reading also included the book Infantry Attacks by the future “Desert Fox” Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (who commanded the 7th Armored Division in France), as well as Achtung, Panzer! by tank theorist Guderian who, in turn, read the works of the British tank writers J.F.C. Fuller and Captain Basil H. Liddell-Hart.

Germans Run Through Several War Plans

Overall, the planning process for Case Yellow ran from October 1939 into February 1940. From their intelligence the Germans knew that the Allies planned a war of attrition. In his postwar memoirs, Lost Victories, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein wrote that the first two plans were but partial offensives for territorial gains only: “The territorial objective was the Channel coastline [not Paris, as in 1914]. What would follow this first punch we were not told.”

What he did not know at the time—or did he?—was that, as he later wrote, “the [Case Yellow] plan had come from Hitler” and “contained no clear-cut intention of fighting the campaign to a victorious conclusion. Its object, quite clearly [was] defeat of the Allied forces in northern Belgium and … possession of the Channel coast as a basis for future operations.”

The first plan was issued on October 19, but changed 10 days later to reflect, as Col. Gen. Alfred Jodl noted in his diary, Hitler’s “new idea” about having an armored and a motorized division attack Sedan via Arlon.” Thus, the Schwerpunkt (strong point of concentration) of the overall main attack was shifting from the northern wing through neutral Belgium and Holland into the heartland of France herself, but only as General Fedor von Bock’s Army Group B was well on its way to taking the French coastline ports for an expected invasion of Britain. Two more versions were issued, on November 15 and 20, with the same “new idea” of an attack through the 1870 German victory (over Napoleon III) battleground of Sedan, although the main thrust remained through Belgium in the north.

What had happened to change the military focus? Von Manstein later said the idea was his. He feared an Allied assault through the same Ardennes into the Reich. Halder, too, was coming around to the view that the thrust there was critical, but only for a single prong of the armored punch, not the main one.

Crash Landing Nearly Ruins German Plans

This was where matters stood as New Year 1940 arrived, with Case Yellow set to commence no later than January 17. But then on January 10, an event occurred that almost wrecked the entire German offensive and very nearly resulted in the firing of Göring by an enraged Adolf Hitler.

A German plane flying by mistake over Belgian territory crash-landed. A Luftwaffe officer had with him General Order of Operations: Air Fleet 2 that detailed the German invasion plans for Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg. He attempted to burn them but failed; the Allies had the plans.

Hitler was furious. One observer called it “the greatest storm I ever saw in my life. The Führer was possessed, foaming at the mouth, pounding the wall with his fists and hurling the lowest insults at the ‘incompetents and traitors of the General Staff,’ whom he threatened with the death penalty.”

Germany Moves Attack Through The Ardennes

Two days after the aircraft incident, von Manstein intervened again, proposing “the transfer of the center of gravity of the attack to the Meuse between Dinant and Sedan.” Manstein wrote that Hitler received the idea with delight. “With astonishing speed he grasped the points of view which the Army Group (A) had been defending for months. He gave my idea full approval.”

Meanwhile, as winter gave way to spring, the Supreme Commander of Allied Ground Forces French General Maurice Gamelin believed that the German attack would come on May 8, 9, or 10 and that he was ready for it. The Allied idea was that once the Germans attacked and Belgium was actually in the war they would utilize their Dyle Plan, which called for advancing against von Bock’s Army Group B in Belgium. Unfortunately, this was just what the Germans wanted them to do. It would make it far easier to get into their rear with an advance through the Ardennes.

The Allies believed they could hold the German attack into Belgium and that German divisions would merely break their teeth on the Maginot Line, if they dared attack it. Their fatal miscalculation concerned the thickly forested Ardennes. Believing that no German force of great strength could come through this region of tangled trees and poor roads, Gamelin placed his thinnest defenses there.

Doubts from Hitler’s Commanders

Ironically, no Wehrmacht commander (except von Manstein) believed that the main effort should be here, and the man who actually would command it, von Rundstedt, didn’t believe it could succeed. Overall, the only man who steadfastly believed that the entire German offensive would be a resounding success was Adolf Hitler.

On the night of May 9, as the Führer’s special campaign headquarters train (code-named Amerika) sped north and west to launch what was now code-named Danzig, he toasted his staff with the words, “Gentlemen, you are about to witness the most famous victory in history!”

At first, the Führer settled in about 30 kilometers behind the frontier. Later he would move his command headquarters to the Belgian village of Brûly-de-Pesche. There was no doubt who was in charge, or from whence flowed the chain of command.

This was in sharp contrast to the manner in which the Allied forces were operating. First, Churchill was in London with Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) Sir William Edmund Ironside. Premier Paul Reynaud was in Paris and by some accounts overly influenced by his increasingly dictatorial mistress, Countess Helene de Portes, who made—and would continue to make—critical military and political decisions.

Allies Faced Command Unity Challenges

The situation between Allied ground forces chief Gamelin and his subordinate General Alphonse Georges was poor. According to historian Alistaire Horne, “Georges was responsible for fighting a battle according to plans drawn up by Gamelin with an army which Gamelin had moulded to his own concepts. As a result, once the Germans launched their offensive … no one was certain who was actually controlling the battle, and this confusion was compounded by the proliferation of headquarters and an inadequate communications system. (Gamelin had his command post at Vincennes on the outskirts of Paris, while Georges had his main headquarters at La Ferte-sous-Joarre some 40 miles east of the capital, but spent much of his time at his command post—and residence—at Bondons, 12 miles away. A third, Grand General Headquarters, commanded by a major general [chief of staff] was situated at Montry, 20 miles east of Vincennes and southwest of La Ferte, and the C-in-C of the Air Force … had his Headquarters at a fourth place.”)

As for communications, the Germans used the very latest in radio, radio-telephone, and teletype—even in the command vehicles of both Guderian and Rommel. Such was not the case with the French. Writes Horne: “The telephone network was totally inadequate and there was no teletype service between these HQ or any of them and the armies in the field. Most dispatches were sent by motorbike, but as several riders were killed in accidents or ended up in a ditch, this must have proved as unreliable as the telephone. Consequently, it took the Army six hours to tell the Air Force which targets it wanted attacked and Gamelin later calculated that it took 48 hours for one of his orders to arrive and be executed by those in the field.”

Germans Outnumbered, But Had Other Advantages

Nevertheless, the Allies were confident as could be. In fact, they held no war games during the “Phony War,” only awards ceremonies. In the Ardennes, moreover, while the citizen-soldiers should have been practicing firing their rifles, they were instead filling sandbags and digging foxholes. Thus both sides prepared, in their way, for the approaching conflict.

Pallud says the Germans fielded 157 divisions. The total for the Allies, he believed, was 242 divisions, namely 202 French, 20 Belgian, 10 British, and 10 Dutch. Thus, although the Germans could put fewer divisions into the fight, they enjoyed unity of command, common language, and common weapons, ammunition, and vehicles; the Allies enjoyed none of these.

As for armor, the best comparison for the campaign appears in British author Len Deighton’s 1979 work Blitzkrieg. In 1939, he states that France had 260 20-ton Somua S-35s, 950 9.8-ton Renault R-35s, 311 32-ton Char B-1 tanks (considered the best), 545 Hotchkiss H-35 11.5-ton tanks, and 276 Hotchkiss H-39 12-ton tanks. He credits the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) with 75 26.5-ton Matilda Mark II A-12 infantry tanks, 126 14-ton A-10 tanks, and 30 14-ton A-13s.

Against these Deighton says the Germans boasted 1,095 nine-ton PzKw IIs, 388 19.3-ton PzKw IIIS, 410 9.7-ton Czech-built PzKw 38s, an unknown number of Czech-built 10.5-ton PzKw 35s, and 278 17.3-ton PzKw IVs.

“Allied Bombs Could Have Sent Group Kleist Scattering”

A veritable storm of Teutonic armor converged on the forests of the Ardennes on May 10. The immediate result was a terrific traffic jam. It was then that Gamelin could have seized the initiative and blasted the German offensive to a halt. May attests: “At any moment during daylight on May 10th, 11th or 12th, well-aimed Allied bombs could have sent Group Kleist scattering and clogged its advance. In openings between areas of forest, the slow-moving German tanks would have made easy targets. … The weather was perfect for such attacks—clear, almost cloudless, and with only light winds. … Nearly all German aircraft were committed to covering Bock’s movements into the Netherlands and Northern Belgium and helping to create the impression that this was the focus of the German offensive.”

But Gamelin did nothing of the sort. He believed that the aim of the German thrust was to be through Belgium to Paris. In any case, he had very poor coordination with his air chief General Joseph Vuillemin, an irascible man. (Later, Vuillemin would refuse to send planes to aid the RAF in the skies over Britain or to bomb targets in then-belligerent Fascist Italy.)

States Pallud, “While the French fighter pilots were well-trained and motivated, their mounts, though not obsolete, were no real match for the Luftwaffe’s Messerschmitt 109 [just as Colonel Charles Lindbergh had said in 1938-1939]. The most numerous fighters were the Morane MS 406, of which 296 were in service, and the Curtiss H-75, 99 being on strength.… Without doubt the best of the French fighters was the Dewoitine D 520, which could fight on equal terms with the Bf 109, but there were only two fighter groups operational with the type. … Three more groups would be equipped with the aircraft before the Armistice, and the Dewoitine was to be credited with 147 victories in just over a month against the loss of 85 aircraft and 44 pilots.”

Army, Air Force Failed To Use Equipment Properly

Oddly, Vuillemin ended the campaign with more first-line fighters than he had at the start. The French aircraft industry in late 1938 produced 30 planes a month, a year later 300 a month, and made a heroic effort in May 1940 by producing 500 aircraft. Unfortunately, the French did not have enough pilots to fly them.

The same muddled thinking of the French Army infected its air force. Noted World War II observer William Shirer wrote, “As in the case of tanks, the FAF would suffer from the failure to use its aircraft properly. Again as with the tanks, too many machines were assigned to the land armies, each of which had its own fighters, reconnaissance and observation planes, over which the Air Command had no control. There was confusion in the Air Command itself. Its chief, Gen. Vuillemin, would never really control operations. No one would…. Timely air operations [were] almost impossible.” In general, the French did not appreciate the role aviation could play in modern war.

Altered Route Gives Germany A Victory

In any event, the weather was excellent for air operations. Ju-87 Stukas bombed troop concentrations, pillboxes, supply lines, airfields, and other strongholds, setting onto the French highways about 15 percent of the population—five million people. The clogged roads hurt the Allied forces heading east more than the German formations heading west. The skies were also kind to German paratroopers and glider forces—more new weapons. These captured key Belgian forts and bridges. What bridges the Allies did manage to blow up did not stall the Germans for long. They forded rivers and canals with individual rubber pontoons, and later larger footbridge pontoons for artillery and vehicular traffic.

True to their plan, the British and French armies advanced into Belgium believing they would there fight the fateful battle against Germany’s main effort. It would have been had not the Germans changed the thrust following the plane crash of January 10. Instead, the Germans emerged through the unguarded back door of the Ardennes, north of the Maginot Line.

Thus, by the 13th, the Maginot Line was outflanked. The Battle of Sedan was fought on the 13th and 14th. Von Rundstedt won his breakthrough and sent armor streaming behind the French lines to the north. The next day, Holland surrendered, and a plaintive Reynaud telephoned Churchill in London to cry, “We are beaten!”

Belgium Falls, But Hitler Still Nervous

Churchill flew to France to survey the rapidly changing scene for himself. At a meeting with Reynaud, Minister of Defense Edouard Daladier, and Gamelin, Churchill was shown the German breakthrough at Sedan. He asked the French about reserves with which to crush the incursion and was shocked to learn that the French had none; the whole French force was committed to places on the Front Line. On the 17th the Germans took Louvain and the Belgian capital of Brussels. Churchill returned to London believing, at the least, Paris was lost. De Gaulle, however, attacked briefly with his tanks, and would later cause even Guderian some anxious moments.

That same day Hitler drove to von Rund-stedt’s headquarters at Bastogne in Belgium. He put on a brave and smiling face as he gaily saluted his cheering soldiers in the streets, but back at FHQ, Halder wrote in his private diary, “2100 hours. A rather disagreeable day. The Führer is terribly nervous. Frightened by his own success, he fears to take risks and would prefer to curb our initiative.”

Hitler needn’t have worried. There was panic and consternation in the Allied Supreme War Council. Gamelin’s response to the thrusts of German armor over the period of May 12-17 was to redeploy 20 divisions by 500 trains and 30,000 vehicles to plug the gaps in the pierced Allied lines, as had been done in 1914-1918. But, unlike then, the French did not have Göring’s aircraft ranging at will behind their lines creating havoc.

“Yes, This Means The Destruction Of The French Army”

Before he surrendered his office to Reynaud on the 15th, Daladier learned from Gamelin some grim truths in a telephone conversation from Vincennes that was overheard by the American Ambassador, William C. Bullitt, who wrote of it, “The Supreme Commander was calling the Minister. Suddenly Daladier shouted, ‘No! That’s not possible! You are mistaken!’ Gamelin had told him that an armored column had smashed through everything in its path and was at large between Rethel and Laon.

“Daladier was panting. He found the strength to shout: ‘You must attack!’ ‘Attack? With what?’ replied Gamelin. ‘I have no more reserves.’ .… ‘So this means the destruction of the French Army?’ ‘Yes, this means the destruction of the French Army,’” answered the Supreme Commander, in what must have been a mortifying moment for both men.

Churchill’s response was to send 10 more Hurricane squadrons (no Spitfires were sent to France during the battle; they were retained for the defense of Britain) to stem the onrushing Teutonic tide.

The 18th was another critical day, as BEF Commander General Lord Gort began to discover, too, the growing Gallic pessimism over the eventual outcome of the conflict. Marshal Henri-Philippe Pétain was recalled from his post as ambassador to Madrid to become Vice Premier and Minister of State under Reynaud, and Gamelin was replaced outright by General Maxime Weygand from his post as commander of French forces in Syria and Lebanon.

Aging Warriors Return, One With An Agenda

The two aging warriors had been brought back to buck up the flagging faith in the war effort. Pétain, however, returned with a hidden agenda in mind: to seek an armistice with Hitler and purge France of its native Communist elements.

On the 19th, General Giraud of the 9th French Army was captured by the Germans. With his loss the fate of his army began to be sealed, even as de Gaulle launched a second (but ineffective) armored thrust. Gort began thinking of the classic British Army evacuation by sea (rather than continuing a lost land battle) that had been accomplished by Sir John Moore in Portugal during the Napoleonic Wars and that Wellington was prepared to undertake had he been defeated by Napoleon at Waterloo.

De Gaulle engaged Guderian on the 19th, but the German tank theorist brushed him aside and reached Abbeville on the Channel coast. Weygand began establishing the defensive line that would bear his name along the Somme and Aisne Rivers.

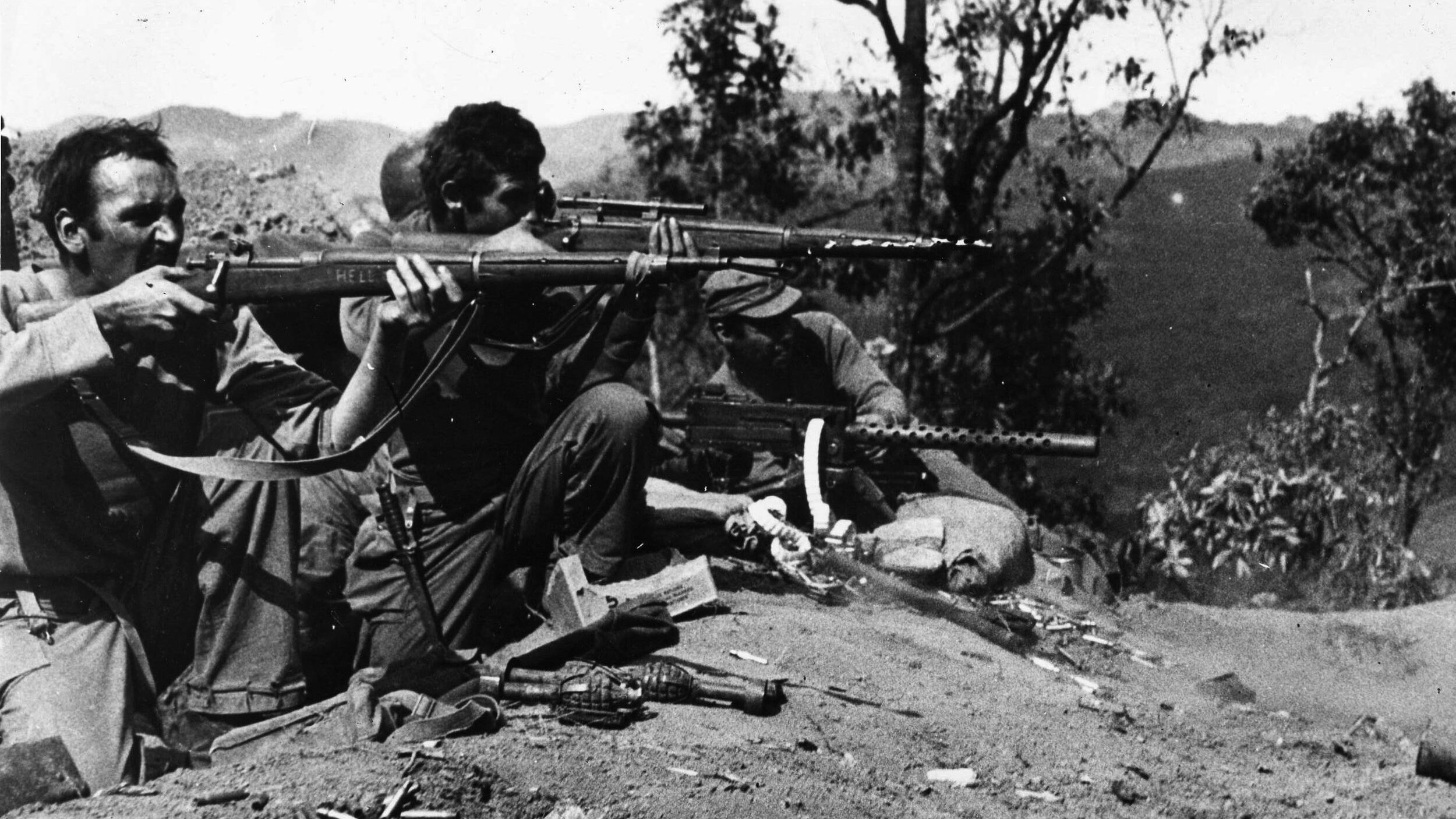

On the 21st, the Germans won the fight at the Mormal Forest and crossed the Somme River, having advanced 250 miles in 11 days. Meanwhile, Gort’s BEF briefly stopped both Rommel’s 7th Armored Division and Himmler’s Waffen SS. The fighting was vicious. Men of the SS Lifeguard Division Adolf Hitler under General Josef “Sepp” Dietrich shot unarmed British POWs of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. Pallud quotes one SS trooper as shouting, “Fellow Englishmen, there will be plenty of room where you’re going!” He also asserts that men of Rommel’s 7th Armored may have massacred French Senegalese soldiers from Dakar for “resisting too long.”

British Soldiers In France Evacuate

By then Gort had decided to effect an evacuation by sea, and convinced his subordinates and superiors that this was the best policy in face of the expected German invasion of Britain when France fell. The French—who later felt betrayed—were misled by their ally to believe that they were regrouping to fight yet another land battle against the common foe, not preparing for a seaborne evacuation to England.

On the 23rd, the BEF evacuated Boulogne and began Operation Dynamo, the evacuation from Dunkirk via the Royal Navy and all manner of private vessels. From then until June 3 and under a rain of Luftwaffe bombs that were largely muffled in the sand, 338,226 BEF, French, and other Allied soldiers were taken on board. All of their heavy guns and transports were lost, but the men, including such later general officer luminaries as Bernard Montgomery, survived to fight another day.

Reasons Behind Hitler’s “Halt Order”

Hitler met with von Rundstedt the following day and enforced his controversial “halt order” that prevented German armored units from advancing into Dunkirk and finishing off the BEF. Many reasons for this puzzling order have been offered over the years: (1) politically, Hitler wanted England to survive, either as an active ally in the coming Eastern Front war or as a passive nonbelligerent that could control its empire while Germany ruled Europe; or (2) von Rundstedt told fellow World War I veteran Hitler that the sandy soil would not support tanks; or (3) Göring boastfully asserted that his Luftwaffe could tackle the destruction of the BEF alone. As it turned out, the Air Force lost 240 aircraft against the RAF in the first nine days of Dynamo, a harbinger of things to come in August.

On the 25th, the French made their last stand at Boulogne, and the next day the Germans took Calais. On the 27th, General Ironside resigned from CIGS and was appointed head of the Home Army to prepare for an invasion of Britain, Rommel got the Knight’s Cross from Hitler, and the Death’s Head Division crossed the Canal d’Aire.

It was at this point, say many armchair historians, that Hitler should have immediately launched Operation Sea Lion against England, instead of turning to annihilate the French Army. Had he done this, though, he would have attempted an invasion such as had not been successful since 1066, all the while leaving a potent Weygand and de Gaulle in his rear.

Belgium surrendered on the 28th, threatening the whole left of the BEF at Dunkirk. During the next two days, the BEF was defeated at Cassel.

On the 31st, Churchill flew to Paris once more to consider the situation with the Supreme War Council. Discussed was the Reynaud-de Gaulle idea of a gradual retreat to Brittany, where a fortified “Breton Redoubt” in the peninsula could be used as a jumping-off point to North Africa. The plan hit a snag, however, when it was pointed out that the French Army no longer had the requisite 12 divisions to man it.

Germans Close In On Paris

On June 1, Rommel arrived in Lille and the 1st French Army surrendered, while de Gaulle proposed to Weygand the formation of two, large, armored formations from the 500 tanks left to France. It came to little. On the 3rd, Paris received slight bombing damage, but this was enough to revive memories of the bombardment from the huge Krupp cannon “Big Bertha” in 1918. What would happen when the Luftwaffe arrived in force—another terror bombing like Warsaw and Rotterdam?

The Dunkirk evacuation ended on the 4th. France fought on virtually alone against the German onslaught. The second phase of the Battle of France, known as Case Red to the German High Command, began the next day with an assault on the new Weygand Line that now ran from the sea at Le Havre to the western end of the Maginot Line.

Weygand had about 64 divisions and used nearly 100,000 troops evacuated from Dunkirk that were quickly relanded in France. Against this force were 143 German divisions, twice the French number and with the added momentum of victory behind them. Despite this, as the overall campaign was being lost, the French fought harder, just as they had in 1814 and as the Germans would do in 1945. Even the Germans noted and commended this stiffening resistance.

Italy Joins Axis Powers, Government Flees Paris

The next day, the Germans reached Soissons on the Aisne River and won the Battle of the Somme. Rommel crossed the Somme on the 7th. On the 9th, Army Group A crossed the Aisne and reached the Seine. Rommel entered Rôuen on the Seine north of Paris.

On the 10th, Italy at last entered the war on Germany’s side (and Franklin Roosevelt condemned it in his famous “hand-that-held-the-dagger” speech at the University of Virginia), Reims fell, Rommel reached the coast, the Germans roamed west of Paris, and the French government fled the fabled “City of Lights.”

While Churchill met with Reynaud at Briare during June 11 and 12, the Germans established bridgeheads across the Marne. As Churchill returned to London, Rommel was accepting the surrender of an entire French corps at St. Valéry, and Guderian reached Châlons-sur-Marne. On the 13th, the Germans broadcast surrender terms for the French, General Hermann Hoth drove on Normandy, von Kleist headed for the Massif and Central Burgundy, Guderian thrust eastward, and von Leeb sent von Witzleben to attack the Maginot Line at last.

That same day, the Germans unleashed Operation Bear across the Rhine River in Alsace and the next day what had eluded the Germans in 1914-1918 became a reality under the Nazis: Paris was declared an open city (and was thus undefended) by its absent government. On the 14th, the Germans took control of the city.

Churchill’s “Franco-British Union” Rejected

Verdun and Bar-le-Duc—scenes of terrible fighting in the previous war—fell to the Germans, “heavy water” necessary to make an atomic bomb was secretly shipped out of France, and FDR signed the Manhattan Project papers that would result in Hiroshima and Nagasaki five years later.

Both Dijon and Besançon west of Switzerland were taken on June 16, and Churchill proposed his “Franco-British Union” idea that would have allowed the two colonial empires to fight on as one even if Metropolitan France fell—Reynaud’s cabinet rejected it. Weygand convinced Pétain that England would soon be defeated; someone at the French High Command said that, “In three weeks, England will have her neck wrung like a chicken.” The last phrase was especially relished and repeated by Churchill during a wartime visit to America when he announced to policymakers: “Some chicken! Some neck!”

On the 17th, Guderian reached the Swiss border, Belfort surrendered, and a second BEF “Dunkirk” was conducted from Cherbourg in Normandy. Pétain took over from Reynaud as premier and broadcast both the reality of France’s defeat and his willingness to seek an armistice with Hitler.

“The Battle Of Britain Is About To Begin”

The next day, Rommel entered Cherbourg, de Gaulle broadcast from London that he and the “Free French” would fight on, and Churchill also took to the airwaves to state: “What General Weygand has called the Battle of France is over. The Battle of Britain is about to begin. … Hitler knows that he must break us in this island or lose the war.” No truer words were ever spoken.

On the 19th, French General Henri Daille took his 45th Corps across the Swiss border into internment, while German General Hoth reached Bordeaux. The German 5th Division took Brest and the 11th Brigade seized Nantes and St. Nazaire—though not before the French battleship Jean Bart escaped.

German General Sigmund List headed down the Rhône Valley toward the French Alps, and von Kleist’s troops reached the Spanish frontier at Hendaye, both events taking place on June 20.

During the period June 20-25, the Battle of the Maritime Alps was fought between the mountain troops of France and Italy, with five French divisions opposing 32 Italian. States Pallud, “The Italians suffered badly with over 2,000 cases of frostbite and more than 600 men reported missing or captured.… In contrast to the Italian losses of 631 men killed and 2,631 wounded, French casualty figures were incredibly light: only 40 killed, 84 wounded and 150 missing or captured.… The French commander, Gen. Olry, had been outnumbered seven-to-one, and thus brought home the only glorious French triumph of the campaign.”

France Signs Armistice

On the 21st, the French lost the Battle of Faulquemont along the Maginot Line—the same day that the Armistice was signed in the famous French railway dining car at Compiégne. On the 23rd, French General Charles-Marie Condé surrendered with 50,000 men, while Hitler and Speer went sightseeing in Paris for the Führer’s sole visit. On the 24th Orléans fell and the cease-fire took effect the next day—when the 220,000 fortress troops of the Maginot Line—unconquered and thus indignant—marched out and into captivity.

Hitler toured the Maginot Line a few days later. Its formal hand-over from the French to the Germans took place on July 1, and today it is a popular tourist attraction. Notes Anthony Kemp of history’s most famous field fortification: “By pinning their hopes on a partial fortification, [the French] placed all their eggs in one basket, to the detriment of the field army. When the time came, the shield was there, but the sword was blunt.”

French Military Was Campaign’s Big Loser

And what of the losses on both sides? According to Pallud, the victorious Germans lost 27,704 men killed, 111,034, wounded, and 18,384 missing and considered probably killed (which Dr. Goebbels compared favorably to German World War I losses at Verdun alone of 310,000 men). The BEF—with 250,000 men at the outset on May 10—lost a comparatively light figure of 3,457 killed and 13,602 wounded. Predictably—despite André Maginot’s best efforts—the French were again the campaign’s big losers, with 92,000 killed, 250,000 wounded, and 1,450,000 prisoners-of-war, whom the Germans held politically over the head of Marshal Pétain until the Liberation in 1944.

At 1:35 am on June 25, Hitler and his staff observed the beginning of the cease-fire in a darkened room by means of a short, silent ceremony, at which Speer was present. “Outside,” Speer wrote, “a bugler blew the traditional signal for the end of fighting. A thunderstorm must have been brewing in the distance, for as in a bad novel occasional flashes of heat lightning shimmered through the dark room.”

This 1940 battle in the West was indeed finished, but the great whirlwind and horror were yet to come.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments