By Kevin M. Hymel

The gunfire has receded with the tide. One of the most valuable pieces of real estate in Normandy, France, on June 6, 1944, which once crawled with American GIs and German soldiers, now welcomes peaceful visitors from around the world. Huge craters stand as a mute reminder of the firepower leveled at Pointe du Hoc, a ridge that juts out into the English Channel.

In the months before D-day, American bombers unleashed payload after payload on this strategic area. Large German guns stationed here could point east or west toward both American invasion beaches, Omaha and Utah. On June 6, American battleships and destroyers brought the Pointe under fire. When the fire lifted, American Rangers assaulted the cliffs, clawing up grappling ropes and ladders, while German fire rained down.

Almost anything that could go wrong for the Rangers did. The rocket barrage that preceded the attack fell short, men landed in the wrong area, and most of the grappling hooks, waterlogged from the storms that rocked the English Channel, fell short. Despite the mistakes and miscues, the Rangers took the Pointe, discovered that the huge guns had been pulled farther inland to escape the bombardment, found them, and destroyed them.

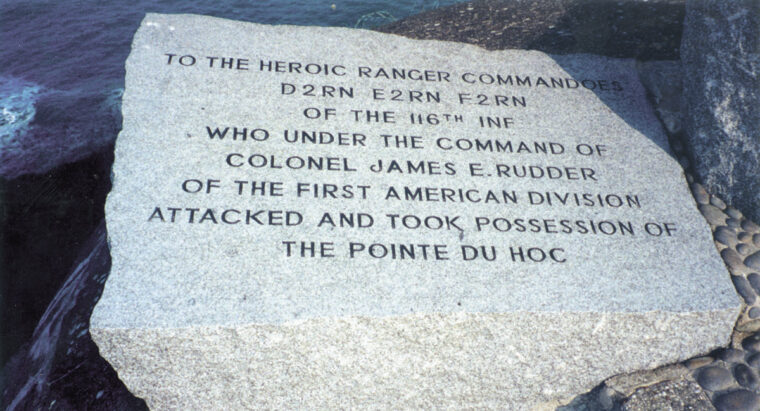

Today, the German gun ports and observation bunker still dominate the Pointe. Craters 10 meters wide and up to two meters deep give the ground a lunar look, save for the grass. The memorial to the Rangers with its obelisk and tablets stands as a simple reminder of the sacrifice a handful of men made to ensure the entire D-day operation was a success. The memorial is not easily accessible. French authorities have surrounded it with barbed wire as the area is crumbling. Tourists have to pick their way through the wire, much like the Rangers of 1944, to view it.

The base of the Pointe cannot be reached from the top. Anyone wishing to experience the herculean endeavor from the Rangers’ point of view must take a charter boat, or make the two-mile walk from the nearest town. The visit has to be timed to prevent getting washed out with the high tide.

Sixty years after the famed D-day assault, Pointe du Hoc is still a daunting geographic and man-made formation. Tourists are drawn to its impressive layout. It is easy to understand the position’s strategic importance to Allied and Axis commands. In Axis hands, it could have turned back the invasion. In Allied hands, it guaranteed victory.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments