by Donald J. Roberts II

In theory, sealing off Southern seaports was supposed to cause economic ruin in the South, which in turn would diminish the Confederacy’s ability to wage war. However, gaining control of the Mississippi River was to have more of a direct impact on military strategy. If Union forces in the West were to penetrate into Confederate territory as planned, it was critical that they obtain control of the river. If the North could not, it would be forced to defend extended lines of land communication.

As the war progressed, Confederate guerrillas became skilled at destroying Union road and rail communications. Consequently, it became increasingly important for the Union to capture the Mississippi River. At the same time, securing the river would sever the Southern states into two parts, making it difficult for Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas to supply the eastern portion of the Confederacy with men, food, and other materials of war.

Winfield Scott’s Plan

Union General Winfield Scott wanted to build an army of at least 60,000 troops, plus a flotilla of gunboats, and then establish a line of depots along the Mississippi as he pushed his forces south down the river. He hoped that by using the river to outflank enemy positions, it would be easier to eliminate them from the struggle. Scott’s plan envisioned this northern Union force eventually linking up with the Union squadrons blockading the Gulf Coast, thus severing the Confederacy and enveloping the two parts.

[text_ad use_post=”455″]

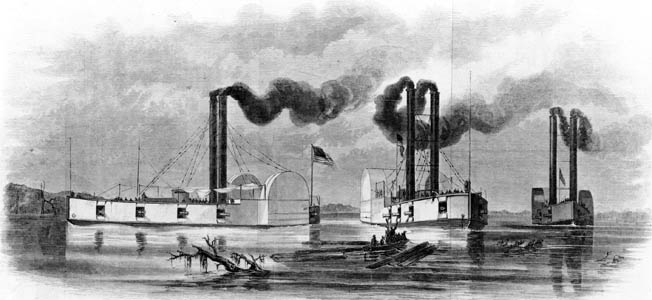

President Lincoln authorized the construction of ironclad gunboats for Scott’s offensive. Scott, however, did not want to delay his attacks any longer than necessary. As a result, Scott had to settle for gunboats converted from steamboats to support his combined operations along the western waterways. Commander John Rodgers bought three side-wheelers; by the time of Grant’s attack on Belmont, they had been transformed into river gunboats. These were the Tyler, Lexington, and Carondolet.

These newly converted gunboats averaged 180 feet in length, 42 feet in the beam, and six feet of draft when fully loaded. Each could reach a speed of 7 to 10 knots. As for armament, they were a heterogeneous lot. The Lexington had two 32-pounders and four 8-inch guns; the Tyler was armed with one 32-pounder and six 8-inch guns, and the Carondolet had only four 32-pounders. All were smoothbore.

Retroffitng the Defenses

These early gunboats were constructed of wood. For added protection, slabs of five-inch-thick oak were added during the conversion. But this only proved to be protection against musketballs. When possible, barges were tied to the sides of each gunboat in order to protect the hull and paddlewheels.

To serve as crewmembers on these early gunboats as well as on some of the newer models, the Department of the Navy ordered some five hundred seamen from eastern seaports to serve along the western waterways. These experienced sailors from Boston and Philadelphia gave commanders like Walke a huge advantage on the rivers.

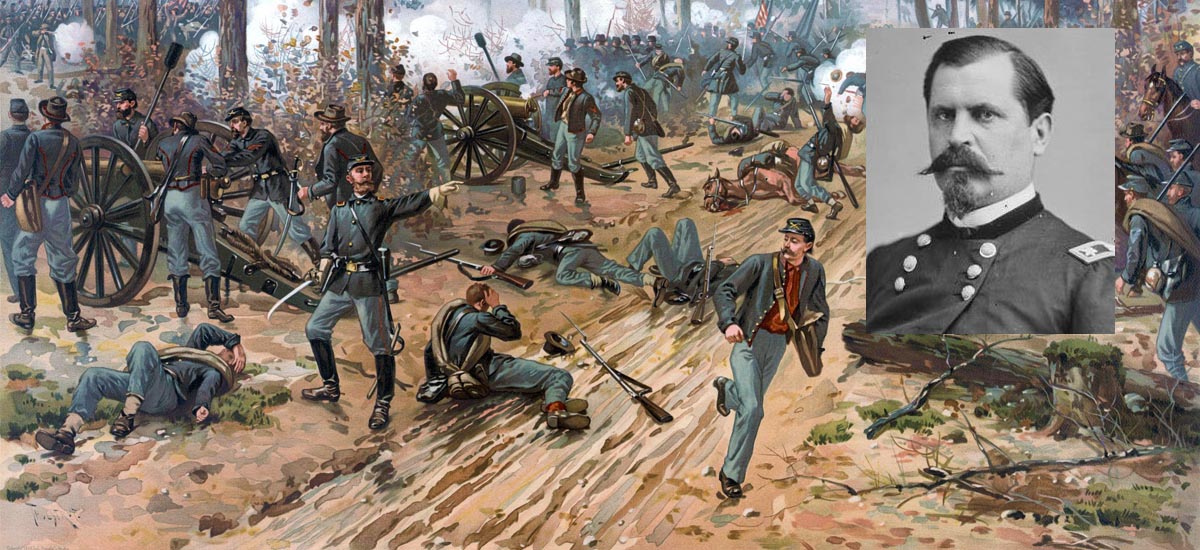

When campaigns along the western waterways required the use of combined operations, and most of them did, the gunboats came under the direct command of army officers in the field. The most difficult aspect of this arrangement was, as in the case in the Battle of Belmont, the failure of effective communication between the army general and naval commander. However, as the war progressed, communications between each branch improved. Possibly the biggest reason for this improvement was that army commanders came to realize how decisive riverboats could be if used effectively in battle.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments