A master of the tactical defensive posture, the Duke of Wellington, later known as the “Iron Duke” for his military prowess, chose his ground well at Waterloo. Wellington recognized the potential strength of his deployment along the Mont-Saint-Jean Ridge and planned to use the escarpment as an impediment to any frontal assault undertaken by Napoleon Bonaparte’s French Army.

[text_ad]

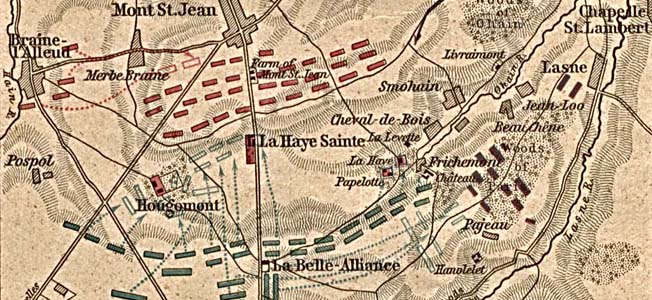

Wellington placed the bulk of his command on the reverse slope of the ridge astride the road to Brussels, offering some protection from enemy artillery bombardment while also concealing his numbers and troop movements from French eyes. On the forward slope he deployed a heavy skirmish line and sent troops to occupy key farmsteads that included, right to left, Hougoumont, La Haye Sainte, and Papelotte. These key positions consisted of orchards, country houses, stone walls, and courtyards. Their strong defense would serve as a breakwater, slowing down the progress of French assaults against the ridge and Wellington’s main line.

Reinforcing Their Position

With both his flanks securely anchored, Wellington chose to place greater strength on the right side of the Brussels road since the Prussian Army under Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher was expected to reach the battlefield to his left and offer support in that sector as the fighting progressed. With his polyglot army of roughly 68,000, Wellington was matched fairly evenly in terms of strength. Napoleon brought 72,000 troops to the field; however, he did not have to contend with language barriers or the lingering concern that haunted Wellington regarding the combat reliability of untried coalition troops.

Scarcely a half mile of wheat fields separated the contending armies at Waterloo, and Napoleon told his subordinate marshals that he intended to unleash a heavy artillery bombardment against the enemy line, order his cavalry to charge in order to fix Wellington’s positions of greatest strength, and then launch a decisive attack with the veteran infantrymen of his Old Guard, the finest troops in his army.

Two Crucial Decisions Sealed Napoleon’s Fate

Prior to firing the first shot of the Battle of Waterloo, Napoleon made two crucial decisions that undoubtedly contributed to his eventual defeat. He believed that at most only a portion of Blücher’s Prussian Army was on the march to Waterloo rather than his entire command. Therefore, Napoleon ordered a large force under Marshal Emmanuel de Grouchy to follow the Prussians closely rather than marching rapidly to Wavre to delay the Prussian advance to Wellington’s aid. Grouchy compounded the error by failing to exert his own initiative and following his orders to the letter, even after he heard the roar of cannon from the battlefield at Waterloo. Thus, Napoleon was deprived of a significant number of troops during the battle, and Grouchy contributed little or nothing to the day’s effort.

In every battle, time is of the essence, and Napoleon — probably out of necessity – postponed his main attack at Waterloo for approximately four hours. The reason was simple. Throughout the previous day, heavy rains had turned dirt roads into quagmires. Cavalry and artillery could not move easily in the mud. Horses would tire more quickly, and artillery shells might lose a measure of effectiveness, miring in the muck rather than exploding and showering the enemy with deadly shrapnel.

The delay would allow the ground to dry somewhat, but it also provided precious time for the Prussians to close the distance. Although he approached Waterloo with a reputation for winning, veteran troops, and high morale, Napoleon evened the odds with Wellington to a degree at Waterloo before the fighting began in the late morning of June 18, 1815.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments