By Blaine Taylor

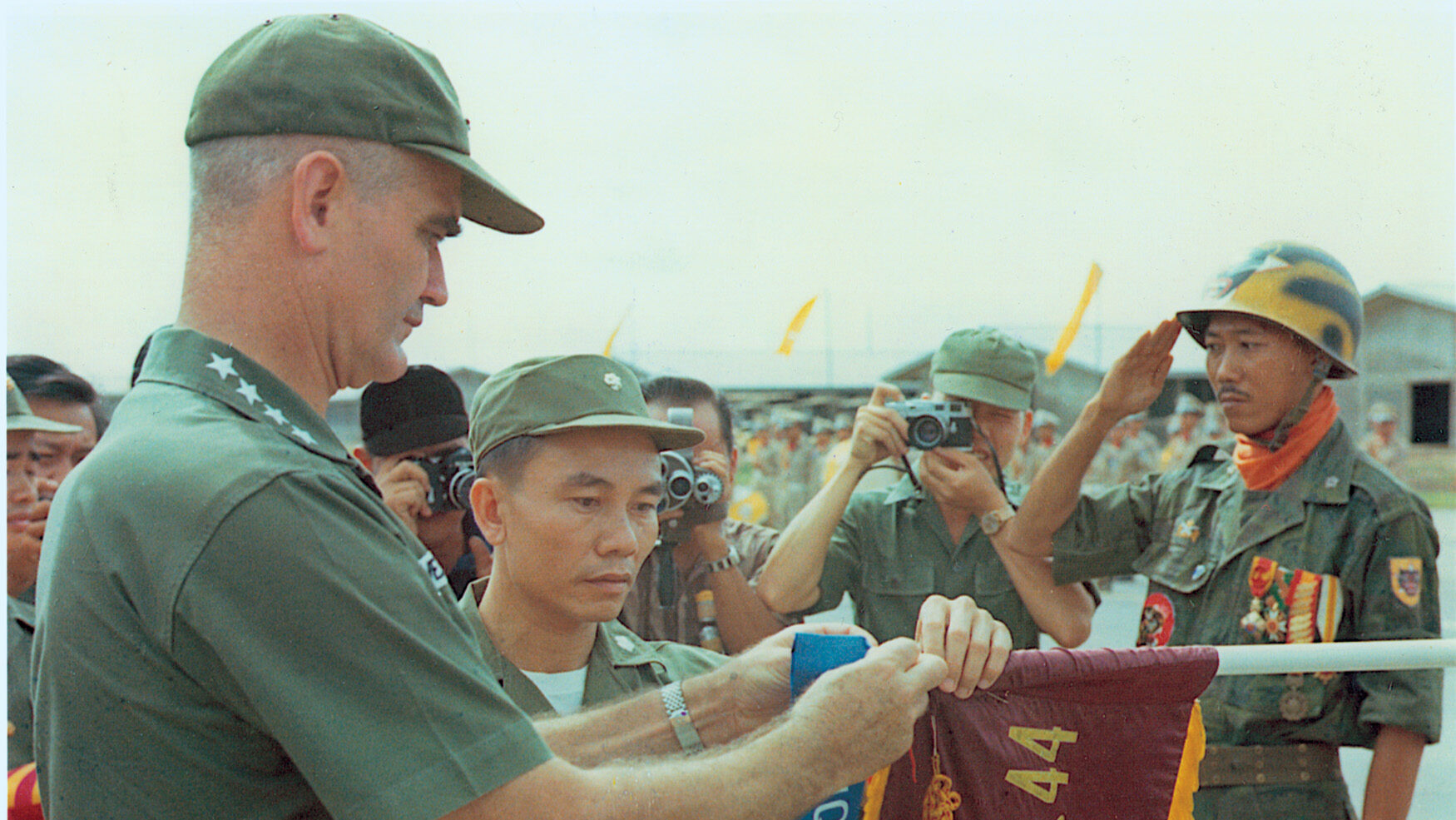

In 1989, this writer had occasion to interview four-star General William Childs Westmoreland, now 86, formerly U.S. military commander in South Vietnam and at the time of the interview a retired Chief of Staff of the Army.

Not only had I read his memoirs just a few days before our meeting, but I had also served in the Vietnam War myself as an enlisted man of the U.S. Army 199th Light Infantry Brigade during 1966-1967, and thus had my own perspective on the struggle. When I met him in 1989, the general had already been a top soldier, pilot, diplomat, warrior, and confidant of presidents. He was still the ramrod-straight imperial proconsul of my youth.

Westmoreland was the nation’s number one Vietnam vet whose wife, Kitsy, lost a brother killed in the war, LTC Frederick Van Deusen. Westmoreland is still speaking about the war and taking part in memorial marches around the United States. He told an earlier interviewer that the hardest decision of the war for him was to recommend to President Lyndon Johnson that U.S. ground combat forces be committed to Southeast Asia to shore up the flagging South Vietnamese effort there in 1965.

“LBJ,” he recalled, “always did what he said he would do.… During his first year in office, 1964, we went from 500 advisors to 15,000 military personnel.… I don’t dislike [then Secretary of Defense] Bob McNamara. He was fair to me.… We were actually operating in the unknown,” he once told veteran Vietnam writer Laura Palmer. A decade earlier, at the time of the French defeat, Westmoreland—then an army general staff officer during the Eisenhower Administration—had been in on the discussions about whether or not to send U.S. troops to aid the French Foreign Legion paratroopers and Vietnamese colonial troops to defeat the Viet Minh, the predecessors of the Viet Cong.

Westmoreland took part in the final decision in 1954 not to send U.S. forces. He later recalled: “All the negatives were exposed. Had I not been in on them, my doubts about the wisdom of committing American troops in 1964 might not have occurred to me.”

”It was Evident That America Was Not Going to Make Good its Commitment to the Vietnamese”

In early 1968, he told Palmer, “Tet was our last chance. The Tet offensive was a terrible gamble by the enemy, and they were crushed. After that defeat, I think there was a really good chance of bringing them to the conference table, but public opinion was disgusted with a war that was dragging on and on. … I object to saying that was the point when the war was lost. That was the point when it was evident that America was not going to make good its commitment to the Vietnamese.

“We had thrown away all our trump cards when we finally got them to the conference table in Paris. Their big trump card was the POWs. We didn’t have any trump cards because we were already withdrawing our troops. We’d even sanctioned letting their troops remain on South Vietnamese soil.”

By 1968 Westmoreland had come home from Vietnam to assume his new duties as Chief of Staff of the Army, the highest post a soldier can aspire to. He resigned in 1972 after a 40-year military career that spanned horse-drawn artillery to nuclear missiles. In the 1980s, he would spend $60,000 of his own money to clear his name in a controversial lawsuit against Columbia Broadcasting System television.

Westmoreland was from South Carolina; his ancestors fought for the Confederacy. His father wanted his son to become a lawyer. “Informed and well-read, he encouraged me in a broad range of activities, from studies to boxing and playing the flute,” recalled the four-star retired general in his 1976 memoirs, A Soldier Reports. Famous friend James F. Byrnes (South Carolina Senator, Secretary of State) steered him instead from South Carolina’s famous military school, The Citadel, toward West Point. He was graduated as an artillery officer in 1936 and soon had served in army bases around the country.

Mid-1941 found him stationed at Ft. Bragg, NC, with an artillery unit of the 9th Infantry Division. When the United States went to war, Westmoreland went with the army to Tunisia.

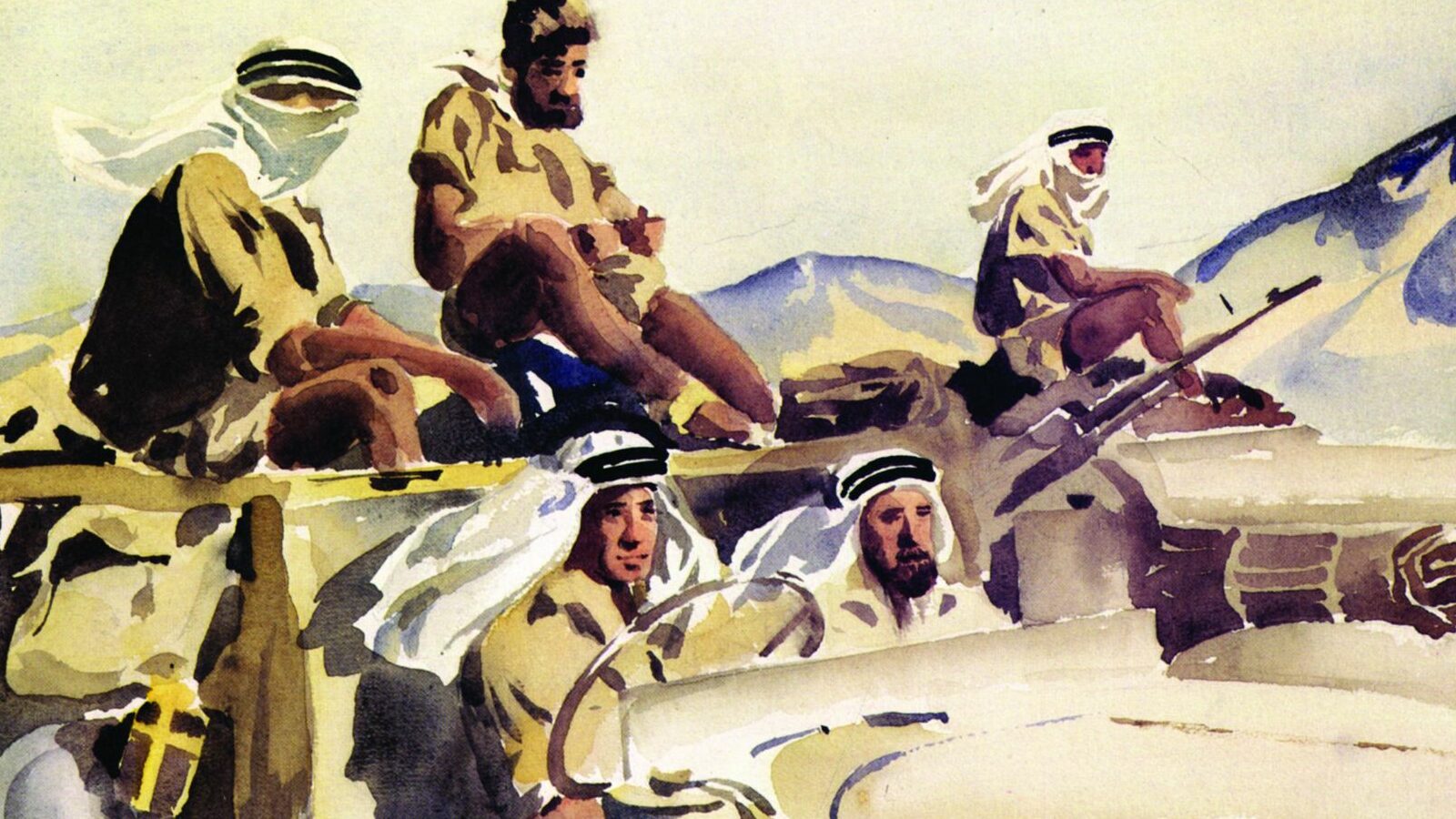

I asked him to discuss his role at the Battle of Kasserine Pass in 1943, and he recounted the following: “We made a forced march from Algeria to Tunisia in the middle of the winter. I was the first American to arrive before this beleaguered British brigadier who was in command in a CP in a basement. He just had a road map on the wall, and a German tank was burning outside. I got there about 2 am. I asked him what the situation was. He was very cool, calm, and collected and said, ‘Well, I have a few tanks left and one platoon of infantry,’ and that was about it. He said he was glad to see us!”

“Have You, Personally, Physically, Ever Killed Anybody?”

Next, we talked about his role in the invasion of Sicily in 1943. “I went in with combat troops of the 9th Infantry Division,” he recalled. “I saw quite a bit of action there. I was shot at a lot. A mine we ran over destroyed my vehicle, but it was well sandbagged, so only it was blown up. I went down to the aid station, where a doctor checked me over and gave me a shot of whiskey—but [laughing softly] no Purple Heart.”

“Have you, personally, physically, ever killed anybody?” I asked. “Not knowingly,” was his reply.

We discussed his crossing of the Remagen Bridge in March 1945, the later battles in Nazi Germany, and his view of General George S. Patton. “I was chief of staff of the 9th Infantry Division. I was one of the first persons over and led the division headquarters across in the middle of the night. At that time, we had one regiment across the Ludendorff Bridge, and finally we brought the whole division over to the German side of the Rhine. The Germans were bringing mortar fire on us. I also went through the Siegfried Line and the Battle of the Hurtgen Forest, which was a terrible mistake, one of the major mistakes of the war. It just chewed up one, two, three, four—about five divisions. My division got chewed up twice there!

“I liked Patton,” he continued. “I knew him when he was a lieutenant colonel. He visited my unit in North Africa, I saw him in Sicily, and I saw him in Germany after the war, shortly before he died. I knew Patton very well, and we had a good rapport.”

Commanding the division’s 60th Infantry Regiment during the Allied occupation of the blasted Third Reich, Westmoreland later remembered, “I had to relieve two battalion commanders for improper conduct and to prefer charges against a captain for stealing furs.”

Westmoreland Strikes the Balance of Stalwart, Yet Charming With His Troops

But if Westmoreland did things “by the book,” he was not a man without humor. He recalled a wartime visit of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to the 9th early in 1944. “When he arrived to address the assembled troops, he went at first not to the speaker’s stand, but behind a small outbuilding. He reappeared minutes later, deliberately buttoning his fly, making sure no one missed the reason for the delay. The troops loved it.”

In mid-1951, Westmoreland assumed command of 187th Airborne Combat Team as the Korean War was still raging against the Red Chinese and the North Korean armies. Almost killed by an errant mortar round from his own side, Westmoreland later found himself and his men beset by attacking Chicoms. “When a Chinese Communist attack drove a salient into the lines of two adjacent units, it left my combat team holding a critical shoulder of the salient.” Ordered to withdraw twice or be relieved of command, he did so, but only under duress and a direct order.

I asked the general to give me his impressions of the Red Chinese Communist troops he had fought in Korea. He recalled: “They were like a herd of sheep, just poor peasant boys. They didn’t know how to fire their weapons and they didn’t have too much support, either. Somebody would blow a bugle, kick them in the butts, and they’d move forward! They didn’t mind dying. They used massed manpower against our massive firepower. The carnage was terrible.”

Back in Washington, Westmoreland was assigned to Pentagon duty. By 1958 he was in command of the 101st Airborne Division based at Ft. Campbell, Kentucky. In 1960, President Eisenhower named him Superintendent of West Point.

VIP visitors to the Point during Westmoreland’s tenure included Vice President Johnson, JFK, novelist William Faulkner, and General MacArthur, who made his famous “Duty, honor, country” speech there in 1962. Trapped in an old elevator that dated back to MacArthur’s days as a cadet, the two men rode up and down until they came to the right floor. When Westy passed along a request by press photographers for the old man to remove his hat, MacArthur testily replied, “I will take off my hat when I am ready. Don’t pay any attention to them!” Later, during the review of the Corps of Cadets, Westmoreland recalled, MacArthur removed “his hat with a flourish” and “placed it over his heart.”

Westmoreland continued about MacArthur in this vein: “MacArthur was quite an unusual man, and of course had spent many years abroad in the Far East. Consequently, he had a distorted view of the world. And his knowledge was pretty much confined to war. He was very fond of Chiang Kai-shek, and felt that he personified the future of that part of the world—which was quite wrong. As a result of that, the Korean War was not as well handled as it might’ve been.”

Westmoreland also met President Kennedy. “I found him to be a good and fascinating man. If he had finished his term he would have been able to handle better the public relations aspect of Vietnam. After all, he gave that magnificent Inaugural Address in which he said there was no price too great to pay in the defense of liberty. That was rhetoric that the American people loved—and they bought it!”

Westmoreland’s next assignment, in 1963, was as commander of the 18th Airborne Corps at Ft. Bragg. He then received orders late that year to go to Vietnam as the deputy to General Paul Harkins, from whom he eventually took command.

The Ground/Air Dilemma

In November 1963 the president’s New Frontier administration had condoned the overthrow of the South Vietnamese dictator, President Ngo Dinh Diem. The fall of Diem, Westmoreland later felt, was a major factor in Saigon’s political instability and the prolongation of the war. As Westmoreland notes constantly in A Soldier Reports, the weapon most feared by the enemy was U.S. airpower, particularly the deadly U.S. Air Force B-52 bombers, and yet—right from the start—the use of this weapon was dictated by Washington and not left up to the soldiers and airmen on the spot, as in prior wars. Thus, increasingly, Westmoreland’s twin dilemma was that there would be no overall ground victory with U.S. troops, but absolute defeat without them. Rather than a massive influx of U.S. troops into South Vietnam all at one time, a gradual buildup or escalation began, a seemingly never-ending process that grated on the American public back home and was ineffective in the end.

According to his postwar A Soldier Reports, Westmoreland was already talking about invading the Red “sanctuaries” in neighboring Cambodia—five years before Nixon ordered them cleaned out by invasion in May 1970.

U.S. airpower, too, was increased in the form of more than 3,000 army choppers in the skies over South Vietnam by the end of 1967. That same year, U.S. Army General Creighton Abrams—a tanker under Patton at the Battle of the Bulge in 1944-1945—was picked as Westy’s ultimate successor. “The war was going well,” Westmoreland noted, when—unknown to him then—North Vietnam, in July 1967, decided on the Tet Offensive for the following January 1968.

32,000 Dead, 5,800 Captured

Westmoreland remarked on the breadth of the attack but noted also that it was over 12 days later with the enemy completely routed, leaving behind an estimated 32,000 dead and 5,800 captured to 1,001 Americans killed and 2,082 South Vietnamese and Allied troops killed. “Nothing remotely resembling a general uprising of the people had occurred,” he wrote in his memoirs, although this is what the Communists had both expected and predicted. “It all added up to a striking military defeat for the enemy on anybody’s terms,” but not, alas, on the U.S. political home front for the presidential election year of 1968.

Throughout the war, Westmoreland’s greatest fear had been a catastrophic land defeat of his forces by the enemy, à la the Battle of Dien Bien Phu against the French in 1954, and he was determined not to lose in this fashion. Thus, he decided to stand his ground at the post-Tet Battle of Khe Sanh, a decision for which Harvard historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. called publicly for Westmoreland’s resignation or firing.

As Schlesinger wrote in The Washington Post on March 22, 1968, “We stay because Khe Sanh is the bastion, not of the American military position, but of Gen. Westmoreland’s military strategy—his war of attrition which has been so tragic and spectacular a failure.… President Johnson likes to compare himself with Lincoln—‘sad but steady’—but he lacks one prime Lincolnian quality: that is, the courage to fire generals when they have shown they do not know how to win wars. Lincoln ran through a long string of generals before he got to Grant. It is not likely that he would have suffered Westmoreland three months.”

LBJ kept Westmoreland on, and the latter noted, in 1976, that “Khe Sanh had evolved as one of the most damaging, one-sided defeats among many that the North Vietnamese incurred, and the myth of Gen. Giap’s military genius was discredited.… Khe Sanh will stand in history, I am convinced, as a classic example of how to defeat a numerically superior besieging force by coordinated application of firepower.”

A Promotion Met With Mixed Emotions

On March 23, 1968—eight days after his own decision not to run for reelection—LBJ announced Westy’s appointment as Army Chief of Staff, and in A Soldier Reports the general noted, “I received news of the appointment with mixed emotions. I had hoped to remain in Vietnam until the fighting ended, yet I was honored by the selection.”

Of the end of the war, Westmoreland wrote in A Soldier Reports: “The defeat was attributable to a variety of factors: the cease-fire agreement of 1973 that legitimized the tactical position of the enemy, putting him in excellent position for later operations, while at the same time dictating the dispersion of South Vietnamese forces; utter disregard by the North Vietnamese of the cease-fire agreement; overwhelming North Vietnamese strength in men and weapons; appalling shortages in the South Vietnamese military forces of spare parts and ammunition; a psychological malaise among the South Vietnamese born of the knowledge that American help was at an end while the enemy’s suppliers persisted; a lack of detailed planning by South Vietnamese officials for that most difficult of all military operations, withdrawal in the face of a powerful enemy; the caution and indecision of President Thieu acting as his own field commander from Independence Palace; and the panic that feeds on panic.”

Next, we discussed his thoughts on director Oliver Stone’s controversial film Platoon. Westmoreland called it “Absolutely atrocious! It gave the impression that murder, rape and manslaughter—soldiers killing soldiers—was commonplace. The director, Oliver Stone, set out with that purpose in mind when he made the film. I court-martialed people for manslaughter in Vietnam or for improper conduct contrary to rules promulgated and given to the troops, which were based on the Geneva Convention. We did everything we could to avoid these kinds of things.

“My theory is as follows: I don’t have to tell you, because you were a young man at the time, but there were others who were running off to Canada to avoid service and doing other things, too, that was also quite commonplace. You’re also quite familiar with the educational deferment policy that was terrible. That type of movie is now very encouraging to those people who didn’t go to the battlefield, because it attempts to support their thesis that this was an evil war and they were not a party to it and they did the right thing. Now it seems to me, and I have no evidence to support this, that the entertainment people in Hollywood, and those who advertise such movies, are in the main taken from that group of people who didn’t go to Vietnam. Making movies about Vietnam as an evil war and a place of atrocities that they were not a part of, in my mind, tends to salve their consciences.”

Work for Peace, Prepare for War

Of the Rambo movies, he said, “The sad thing is that these absurd, extreme movies are also being marketed around the world and thus are the best kind of anti-American propaganda you can find!”

His reaction to American actress Jane Fonda’s controversial trip to Hanoi and later apology for it was both terse and expected: “She seems to be a phony in my book, and she’s conforming to what she perceives as the new wave of public opinion.”

When I asked him which, of all the posts he’d held over the course of his remarkable four-decade-long military career, he had enjoyed the most, I wasn’t surprised when he answered, “Superintendent of West Point. You’re dealing with such wonderful people and the environment is so great! It’s such a beautiful spot, and historically important, too. West Point is the historic personification of the raison d’être of the U.S. Army: To deter war. To deter war, you’ve got to be prepared to fight a war.”

Westmoreland worked to deter war, but he was prepared to fight in war, and he did so in three of them.

I was in Vietnam from 3/38-3/69 so I served under both Westmoreland & Abrams. I’m just one person who was in the war but it seems to me the conduct of the war was the same under both generals.

I served during the war but only stateside. We all talked about the possibility of being sent to Vietnam and were none too happy about it. Westmoreland was a warrior type from the old school and not used to being told how to fight. He had an impossible job and the end result reflected that.