By Frank A. O’Reilly

American Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott captured the port city of Vera Cruz on March 27, 1847, and immediately prepared to leave it behind. Scott had seized the port as a base of operations for his daring campaign against Mexico City during the ongoing war with Mexico. Springtime along the Gulf Coast of Mexico, however, brought with it the seasonal scourge of yellow fever. The disease, referred to colorfully if accurately as “King Death in his yellow robe,” was considered “frightfully destructive” at that time of year. Scott needed to move inland 75 miles to escape the pestilent region. General Antonio López de Santa Anna had a genuine opportunity to hem the American army into the danger zone, using the mountains of the Sierra Madre Oriental to block the route inland to Mexico City. Bermúdez de Castro, the Spanish minister to Mexico, wrote, “Without great labor and preparation an invading force can be destroyed.” If the Mexicans could stall Scott’s drive, the American army would be trapped in the tierra caliente with no ready means of escape.

Scott suffered an embarrassing shortage of transportation and draft animals. He struggled to find adequate resources near the coast but thought the chances would be “much better” inland at the city of Jalapa. The city reportedly had everything Scott needed, and the people allegedly harbored some sympathy for the Americans. “Jalapa,” Scott wrote, “is the first point, from the coast, which combines healthiness, with the reasonable prospect of obtaining some of the heavier articles of consumption for the army.” He reasoned that the Mexicans could not mobilize or interfere with his advance before he reached Perote. The American vanguard started inland on April 2. Brig. Gen. David E. Twiggs’s 2nd Division started for Jalapa on April 8. Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson’s division, minus Brig. Gen. John A. Quitman’s brigade, followed the next day. Brevet Maj. Gen. William J. Worth’s division remained behind to garrison Vera Cruz and await additional transportation.

The mountains to the west could be a significant deterrent to Scott’s advance. The Mexican minister of war bragged that the mountains formed “almost insuperable obstacles against any audacious invader.” Mexicans had started fortifying the passes as early as October 11, 1846, but they made little progress before March 20, 1847. Santa Anna was surprised by the sudden surrender of Vera Cruz. He had banked on the citadel lasting much longer, but he adjusted quickly. He rushed south following his defeat at the Battle of Buena Vista, quelled an incipient rebellion in Mexico City, rallied the nation, and hurried reinforcements east to confront Scott’s invading army.

“At All Cost”

Major General Valentín Canalizo, commanding the Army of the East, looked for a suitable point to defeat Scott’s thrust inland. He focused on the National Highway—or Jalapa Road—as the most likely avenue of advance. It offered the only road surface sturdy enough to accommodate Scott’s heavy cannon. Initially, Canalizo prepared to dispute the Americans “at all costs” at Puente Nacional—the National Bridge over the Río Antigua. The hills dominated the river, but Canalizo had no defenses and his men fled when Twiggs’s Americans approached. The Mexicans fell back to Cerro Gordo, or “Fat Mountain.” Lt. Col. Manuel Robles Pezuela, a Mexican engineer, thought Cerro Gordo had some merit, but it was “not the best point to dispute [Scott’s] passage or attempt a decisive battle.” He recommended Corral Falso, six miles farther west. Santa Anna left the capital on April 2 and reached his ranch at El Encero three days later. Surveying the area east of Jalapa, he determined to fight at Cerro Gordo.

Santa Anna liked how the hills east of Cerro Gordo formed a “narrow, craggy defile that could not be turned.” By halting the Americans there, he reasoned, Scott’s army would “remain within reach of the yellow fever.” An American officer agreed, confessing that “yellow fever appearing in their camp would paralyze the invading army and prove his best ally.” The gorge ran for a mile between Cerro Gordo and the village of Plan del Río. Locals had nicknamed the pass “the Devil’s Jaws.” Three hills formed fingers that dominated the National Highway from the south. Two large round hills, El Telégrafo and La Atalaya, commanded the highway from the north.

Santa Anna concentrated close to 12,000 troops at Cerro Gordo and fortified the three southern hills on April 12. He put Brig. Gen. Luís Pinzón on the far right with 500 men and six guns. Brig. Gen. José María Jarero held the middle ridge with 1,000 troops and eight guns. Colonel Badillo commanded the ridge adjacent to the National Highway with 300 men and five guns. Brig. Gen. Rómulo Díaz de la Vega formed a reserve of 500 grenadiers, 900 members of the 6th Regiment, and six or seven guns.

On April 17, Santa Anna shifted his laborers north of the highway to entrench El Telégrafo. He erected a breastwork on the hilltop, surrounding a stone telegraph station. The 3rd Regiment and four guns occupied El Telégrafo. The hill had a 600-foot escarpment facing east that was considered unassailable. “No army could pass,” Santa Anna reported proudly, “not even a goat could pick his way over them.” The rest of the army was not so sure. Many of them had fought and lost to the Americans before, and overall morale was poor. Numerous officers and men, one observer worried, “represented the enemy as invincible.” Santa Anna’s overweening confidence only exacerbated their fear, and many officers whispered among themselves about an impending disaster.

Reviewing the Mexican Defense

On the American side, Twiggs, nicknamed variously “Old Davey,” “Horse,” and “Bengal Tiger,” reached the defile on April 11 and reconnoitered Santa Anna’s defenses. Lt. Col. Joseph E. Johnston fell seriously wounded while scouting the Mexican right. Captain William J. Hardee and Lieutenant William T.H. “Bully” Brooks finished the mission, reporting somewhat pessimistically that the Mexican front could not be breached. A newspaper correspondent accompanying the army concurred. “The positions,” he wrote, “looked impregnable as Gibraltar.”

Twiggs, never an imaginative commander, ordered a frontal assault for April 12. A critic complained of Twiggs: “His brains were, in fact, merely what happened to be left over from the making of his spinal cord.” Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson’s volunteer division arrived on April 12, and Patterson begged for a day to rest before making the attack. Although senior to Twiggs, Patterson had taken ill and yielded his right to command. When he learned of Twiggs’s plans, however, he recovered enough to resume command and postpone the attack until Scott arrived.

The army commander arrived on April 14 and undertook a careful study of Santa Anna’s defenses. Brooks had discovered a crude trail that led toward the Mexican left flank. Engineer Lieutenant Pierre G.T. Beauregard and Captain Romeyn B. Ayres, of the artillery, investigated, climbing to the top of La Atalaya without being detected. One of Scott’s staff engineers, Captain Robert E. Lee, joined Beauregard on April 15 and 16. Lee was almost captured when he ventured too close to a Mexican post west of El Telégrafo. He hid beneath a log for hours, scarcely daring to breathe, before Mexican scouts moved on elsewhere.

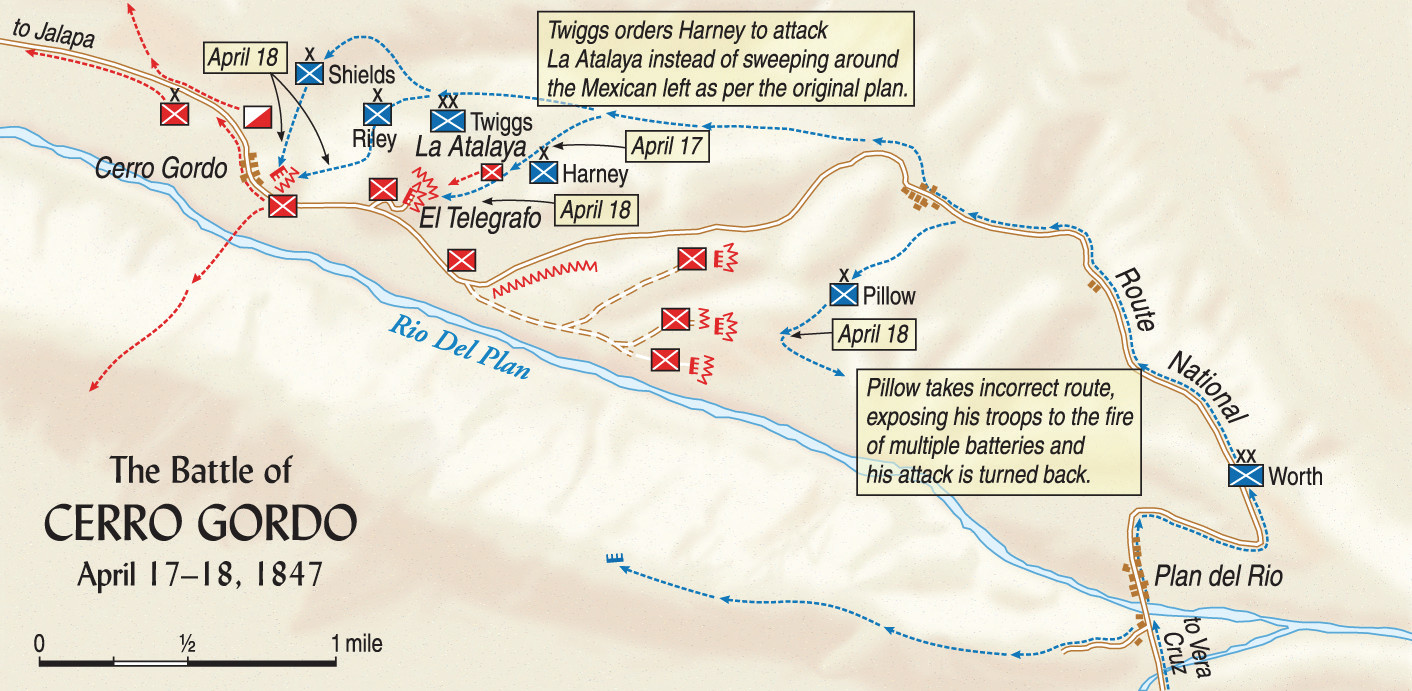

Although the engineers failed to reach the road to Jalapa, they thought an American column could use the rough trail to cut Santa Anna’s line of retreat. Scott agreed. On the evening of April 16, he ordered Twiggs’s division to capture the Jalapa Road in Santa Anna’s rear. Patterson’s division would demonstrate against the Mexican front while Twiggs attacked the rear and Worth’s division would close up in support. Scott’s army of 8,500 prepared to take on a Mexican army of 12,000 men.

“Charge ’em to Hell!”

Twiggs started marching at 7 am on April 17. His division left the National Highway, one mile east of the Mexican defenses, and started down a rough road through the chaparral. Lee feared that Mexican observers might see part of the trail and wanted to screen it with shrubs. Twiggs, however, dismissed the idea as unnecessary. Just as Lee had feared, General Pinzón alertly spotted the column and warned Santa Anna. The Mexican leader sent a small detachment under General Lino José Alcorta to occupy La Atalaya.

Twiggs reached the base of La Atalaya by noon. Brevet First Lieutenant Franklin Gardner of the 7th U.S. Infantry Regiment ran into Alcorta’s skirmishers near the hill. Colonel William S. Harney, temporarily commanding Persifor F. Smith’s brigade, backed Gardner with elements of the U.S. Mounted Rifles and 1st U.S. Artillery Regiment. As Alcorta began to give ground, a captain in the Mounted Rifles asked Twiggs how far they should drive the enemy. “Charge ‘em to hell!” the general bellowed in exuberance. Harney’s men obediently seized La Atalaya and headed for El Telégrafo. The Mexican 4th Regiment blistered the attackers from the brow of the larger hill, pinning down the Americans on the slope. Lt. Col. Thomas Childs’s 1st Artillery Regiment, acting as infantry, had only 60 men on the hill. Within minutes, eight of them were dead and another 23 wounded. Major Edwin V. Sumner rushed to Harney’s rescue, but Sumner was shot in the head and his column bogged down as well. Surprisingly, Sumner survived—the musket ball had failed to penetrate his cranium. Friends immediately nicknamed Sumner “Bull” in honor of his impressively thick skull.

The battle escalated, and Santa Anna counterattacked into the valley between El Telégrafo and La Atalaya. The general, garbed in civilian dress and mounted on a superb gray horse, led his troops down the slope at 3 pm. American Lieutenant Jesse L. Reno planted a mountain howitzer on top of La Atalaya and quickly discouraged Santa Anna from pressing the attack. “The enemy made a demonstration,” wrote an American observer, “but it all ended in their marching down the hill, blowing a most terrific charge on their trumpets, firing a few shots, and then retiring.” The Mexicans withdrew to the top of El Telégrafo, and Harney managed to extricate his forces from the valley after dark. The Americans had lost 90 men, including Sumner. Mexican casualties were estimated at close to 200. “It was a shocking sight to behold,” wrote a private in the engineers, “the poor wounded riflemen with legs shot off, arms gone, and cut in every part … some just alive.” Rain added to the men’s misery during the night.

Pursuit or Defense?

Twiggs’s rash attack upset Scott’s plans for a surprise turning movement. The American presence on La Atalaya gave Santa Anna ample warning of Scott’s intentions—and plenty of time to counter them. Unfortunately for the Mexicans, Santa Anna wrongly assumed that Twiggs’s assault marked the Americans’ principal attack; its failure meant that the crisis had passed. Mexican morale improved with the seemingly easy victory. “Much enthusiasm prevailed among the troops,” wrote a soldier, noting that the Mexicans drew additional inspiration from the fact that they had defeated a Spanish army on the exact same ground during their war of independence.

As a matter of precaution, Santa Anna ordered breastworks built near the base of El Telégrafo. He also summoned reinforcements from the west, including General Manuel Arteaga’s brigade and Canalizo’s cavalry. Brig. Gen. Ciriaco Vásquez assumed command of the El Telégrafo sector. Despite the build-up, most of Santa Anna’s preparations hinted at pursuit rather than strengthening his defenses. It would prove to be a crucial distinction.

Winfield Scott bolstered Twiggs’s force with Worth’s division and Brig. Gen. James Shields’s brigade and ordered another attack before daylight on April 18. He wanted Twiggs to cut the Jalapa Road and seize El Telégrafo. The sound of Shields’s attack would be the signal for Brig. Gen. Gideon J. Pillow’s brigade to engage the Mexican right. Twiggs’s soldiers dragged two 24-pounder cannons and a couple of 24-pounder howitzers to the summit of La Atalaya. The steep slope made it a backbreaking ordeal that required shifts of 500 volunteers to heft each gun to the top. It was “grinding toil and persevering labor for six successive hours,” complained an officer in Captain Edward J. Steptoe’s battery.

Engineers under Lee and Lieutenant Gustavus W. Smith erected earthworks on La Atalaya for the smoothbore guns. The howitzers, however, went into position on the crest “without the slightest protection.” Gunners finally arranged their pieces by 3 am. Meanwhile, four companies of New York volunteers, under Major James C. Burnham, hauled an 8-inch howitzer across the Río del Plan and planted it opposite the Mexican right flank. Lieutenant Theodore T.S. Laidley supervised the placement of the gun. Lieutenant Roswell S. Ripley took charge of the gun and sited it on the end of Santa Anna’s supposedly impregnable defenses.

“That’s the way to murder men!”

American artillery on La Atalaya opened fire at dawn on April 18, blanketing El Telégrafo’s summit at 80 yards’ distance. Their fire proved to be very effective. The surprised Mexicans answered with a sporadic fire that inflicted little damage. “Canister flew over our heads like hail-stones,” recalled an American engineer private, “tearing up the ground and cutting down the bushes, and throwing the stones into the air in every direction.” A rocket battery joined the Americans on the crest and turned its fire on the Mexican encampment at the western base of El Telégrafo. The guns barked for 45 minutes, and then the infantry moved to the attack.

Brevet Colonel Bennet Riley, guided by Robert E. Lee, moved the 2nd Infantry and 4th Artillery Regiments toward Santa Anna’s rear to cut the Jalapa Road. Shields’s brigade followed in close support. Vásquez responded by shifting Colonel José López Uraga’s 4th Infantry Regiment and a 4-pounder gun to a minor crest or shelf on the western face of El Telégrafo. Uraga fired point-blank into Riley’s flank and forced the American officer to detach four companies of the 2nd U.S. Regulars, under Captain James W. Penrose, to take the shelf. Twiggs altered Scott’s orders and directed Riley to attack El Telégrafo with his entire command. Lee protested, but Riley dutifully diverted his troops up the hillside. Lee continued toward the Jalapa Road with Shields’s command.

Colonel William S. Harney concealed his brigade behind La Atalaya until the artillery duel ended at 7 am. “As soon as the firing upon the hill from our guns went silent,” recalled an American artillerist, “the colonel took off his coat, rolled up his shirt sleeves, drew his saber” and ordered his men forward. As Harney charged over the hill, he spotted Mexican reinforcements hurrying to El Telégrafo from his left. He detached part of the Rifle regiment, under Major William W. Loring, to intercept them at the base of El Telégrafo. Loring blocked the Mexican 6th Regiment from reaching the hill, but suffered a punishing crossfire from the Jalapa Road and El Telégrafo. The colonel admired how Loring’s men braved “a most galling fire from the enemy’s entrenchments and from the musketry in front.” Watching Americans cried in horror, “That’s the way to murder men!”

“Roaring Like a Bull”

Harney hurried his attack against El Telégrafo. “I deemed it prudent,” Harney reported, “to advance at once, and immediately ordered the charge.” The 7th U.S. Infantry Regiment led the assault on the right, with the 3rd Infantry Regiment to its left. The 1st Artillery Regiment followed behind. The Mexicans opened fire on the attackers as they cascaded down the slope of La Atalaya. “The shots fell around us,” wrote one soldier, “cutting down the low bushes, and passing through the clothes of some, and cutting down others of the brave fellows that were on to the charge.”

Harney’s men assaulted Santa Anna’s breastworks around the base of El Telégrafo. “About sixty yards from the foot, there was a breastwork of stone,” Harney reported, “which was filled with Mexican troops, who offered an obstinate resistance.” Captain Benjamin S. Roberts of the Rifle regiment wrote, “When dangers thickened and death talked more familiarly face to face, the men seemed to rise above every terror.” Brief hand-to-hand combat drove the Mexicans out of their defenses. Harney’s men chased them up the steep incline of El Telégrafo. “We pushed on, excited and maddened to a complete frenzy,” one soldier reported. The climb, however, took its toll. “The officers were obliged to use their swords for canes to help them up the hill,” recalled an engineer, “as did the soldiers their muskets.” The Americans stopped 75 yards from the crest to catch their breath.

Harney stormed to the front, “roaring like a bull,” to get the attackers moving again. Officers screamed at their men to “Charge! charge!” The soldiers responded with a cheer and a lunge for the hilltop. Americans spilled over the fortifications guarding the summit, and another hand-to-hand battle erupted around the Mexican cannon. “The Mexican loss upon the heights was awful!” related a newspaper correspondent, “the ground in places [was] covered with the dead.” Santa Anna sent two regiments to reinforce Vásquez’s defenders. Vásquez himself soon fell dead, and his chief of artillery, Colonel Palacio, collapsed mortally wounded. General Juan Baneneli assumed command and threw the 3rd Light Infantry into the fray. The Mexicans, however, were outnumbered and nearly surrounded. They broke and fled from the hilltop, carrying Baneneli with them. Sergeant Thomas Henry dashed ahead and planted the colors of the 7th U.S. Infantry on top of the telegraph station.

The Mexican Rout

Santa Anna vented his rage on the officers who had lost their positions, immediately ordering Arteaga’s brigade to retake the hill. Baneneli’s routed command, falling back, disrupted Arteaga’s brigade, which recoiled in confusion. Riley’s regulars, meanwhile, had wrested the spur from Uraga and joined Harney’s command on top of El Telégrafo. Worth’s troops also helped secure the hilltop. Captain John B. Magruder and Lieutenant Israel B. Richardson turned the captured Mexican cannons on the fleeing masses jamming the Jalapa Road below them. A witness wrote of the Mexican panic: “Their loss in retreat was severe—every by-path was strewn with the dead.” An American officer reported seeing “headless bodies, bodies cut in twain, and horribly mangled arms and legs lying about detached from bodies.” Santa Anna tried to counterattack with the 11th Infantry and his grenadiers, but they fell back quickly under American fire.

Shields’s brigade emerged from the chaparral at this time. Lee had led Shields to a point opposite the Mexican left flank and encampment. Santa Anna had posted five cannons on a knoll by his headquarters near the camp. He turned three of these guns on Riley’s force as it climbed El Telégrafo, while the other two opened fire on Shields’s volunteers at a range of 150 to 200 yards. A canister ball pierced Shields’s chest and right lung. The brigade commander appeared to be mortally wounded, but an Irish surgeon with the Mexican Army saved his life by threading a silk handkerchief through the wound to keep it clean. Colonel Edward D. Baker of the 4th Illinois Volunteers assumed command and led Shields’s 300 troops against the battery.

Canalizo’s fresh cavalry, 2,000 strong, stood nearby in support of the guns. Santa Anna ordered Canalizo to charge, but the officer protested that the woods near the road rendered such a mounted attack impossible. Instead, the horsemen panicked and abandoned the field. Baker’s volunteers charged the battery just as Riley and Harney’s men swarmed the guns from the rear. Lieutenant Nathaniel Lyons of the 2nd U.S. Infantry Regiment captured three guns while Baker took the remainder.

Baker’s men linked up with Riley’s and Harney’s troops on the knoll, and together they overran the Jalapa Road. Twiggs’s force had severed Santa Anna’s line of retreat. The Mexican commander, accompanied by generals and staff officers, blundered headlong into Baker’s force, which fired on him and forced him back. Santa Anna abandoned his coach and fled across country, riding a mule. General Juan N. Almonte joined him. The 4th Illinois Regiment captured Santa Anna’s carriage, along with a chest filled with $20,000 in coin and the general’s prized wooden leg. Santa Anna disappeared across the Río del Plan, heading south. The routed Mexican army looked “like a frightened flock of sheep,” according to one U.S. artillerist. A Mexican soldier reported, “Every tie of command and obedience now being broken among our troops, safety alone [is] the object” of the retreat. Officers occasionally tried to rally their troops, but the men ignored them. One Mexican soldier admitted that “badges of rank became marks of sarcasm.”

“A Burlesque of War”

Pillow heard the commotion on El Telégrafo and ineptly advanced his brigade against Santa Anna’s right wing south of the National Highway. His attack degenerated into what one critic called “a burlesque of war.” Of the three ridges commanding the road, Scott wanted Pillow to assault the one farthest to the south, abutting the Río del Plan. Ripley’s 8-inch howitzer stood poised to offer support from south of the river. Pillow inexplicably altered the plan, redirecting his troops toward a draw between the southern and middle ridges. This allowed the Mexicans on both hills to concentrate their fire on the attackers.

The American column fell into disarray and failed to form a cohesive battle line. Pillow wanted Colonel Francis M. Wynkoop’s 1st Pennsylvania Volunteers to assault the north face of the southern promontory, with Colonel William B. Campbell’s 1st Tennessee Regiment in support. At the same time, Colonel William Haskell’s 2nd Tennessee Regiment would take the southern face of the center ridge, and Colonel William Roberts’s 2nd Pennsylvania Regiment would back him up. Strangely, the column divided, and the two reserve regiments ended up ahead of the attacking units. Oblivious to the mix-up, the brigade commander grew impatient. At 9 am, Pillow bristled in anger: “Why the Hell don’t Colonel Wynkoop file to the right?” The general’s loud tirade alerted the Mexicans to his proximity and triggered a barrage of grape and canister. Pillow suffered a slight wound to his arm, “and he retired at a run,” said one less-than-impressed observer, insisting that he had been “shot all to pieces.” Colonel Campbell took over command and ordered an attack.

Pillow’s command split, with some units going forward and others bolting to the rear. The Mexicans repulsed Campbell’s attackers within three minutes. The 2nd Tennessee Regiment lost 80 men, including every field officer except Haskell. The Tennesseans suffered the heaviest loss of any American unit at Cerro Gordo. Pillow returned to the battle—however tardily—and cancelled the attack. He withdrew his brigade into the woods, unaware the Mexicans in front were surrounded. Soon afterward, the Mexicans raised the white flag and surrendered to Scott. The Battle of Cerro Gordo had lasted a little under four hours, ending just before 10 am.

A Stunning Blow to Santa Anna

Scott’s army had inflicted between 1,000 and 1,200 casualties on the Mexicans. He captured approximately 3,000 prisoners, along with 4,000 stands of arms and 40 cannons. In doing so, he netted five Mexican generals—Pinzón, Jarero, La Vega, Noriega, and Obando—and one former president—José Joaquín de Herrera. The Americans, by contrast, lost 63 killed and 368 wounded at Cerro Gordo. Scott lacked sufficient cavalry to pursue the broken Mexican army, but Harney’s dragoons, along with Captain Francis Taylor’s and Captain William Wall’s batteries, pursued the routed Mexicans to El Encero before their horses gave out.

The American army advanced on April 19 and occupied Jalapa without difficulty the next day. There Scott found a safe haven from disease and an abundance of supplies for his army. Santa Anna retreated to Orizaba, collecting only 2,500 troops along the way. Unable to prevent the Americans from seizing Jalapa or Puebla, Santa Anna withdrew to Mexico City on May 11.

The first direct clash between the two great military leaders of the Mexican War had ended in a resounding American victory. Santa Anna had staked everything on Cerro Gordo, hoping to trap the Americans inside the yellow fever zone, deprive Scott of valuable supplies, and block the only route to Mexico City that could support heavy artillery. If Scott had failed to breach the “Devil’s Jaws,” his advance would have stalled, his campaign would have stagnated, and his strength would have atrophied under the strain of yellow fever. Instead, Scott not only fought and won a decisive battle for the health and welfare of his army, but he also destroyed the best resistance Santa Anna could muster, in the best defensive position he could hope to exploit.

The Battle of Cerro Gordo forced the Mexicans to rely thereafter on unconventional warfare, conceding that they had no substantial military force to effectively confront the Americans before they reached the capital. By the time Scott approached Mexico City, the Mexicans had surrendered the initiative and lost any opportunity to maneuver to their advantage. At Cerro Gordo, Santa Anna had lost his best and only legitimate chance for defeating Scott’s American army. General Gregorio Gómez, commanding the Mexican force at La Hoya, reported the disaster at Cerro Gordo with the apt if despairing observation: “All is lost at Cerro Gordo, all, all!” The Americans concurred. Lieutenant Theodore Laidley wrote home: “A few more such victories I think will conquer a peace.”

The is really one of the best of accounts of the battle Cerro Gordo that I have read.

Would you happen to know if the 7th US Infantry was in the 1st or 2nd brigade of the 2nd Division? My sources differ.

Were the 24 pounders on La Atalaya howitzers?

Great article!

Excellent article. See many names of future Civil War generals.

I agree it’s a good read.