By Richard Rule

In May 1941, General Kurt Student’s elite paratrooper forces descended like an anvil on the British garrison defending Crete. Instead of winning a quick and decisive victory, the airborne troops found themselves locked in brutal battle against some of the toughest veterans in the British Army. Here, on the sun-parched Mediterranean island of Crete, the Germans appeared to be on the brink of their first military defeat of the war.

As part of Germany’s peripheral strategy against the British Empire in the Mediterranean, Hitler invaded Greece in early April 1941, with a provision for General Kurt Student’s airborne troops to seize the Greek island of Crete. Within weeks, Hitler’s panzer columns had decisively smashed all opposition in their path and were relentlessly streaming toward central Greece. Allied forces sent to the mainland had been completely outclassed and were soon left contemplating the prospect of another Dunkirk.

While German troops were enjoying incredible success in the Balkans, General Student feared that Hitler had changed his mind regarding the deployment of airborne forces in the Greek campaign. Desperate to get his men into the fight, Student decided to present the case for an air invasion of Crete directly to Hitler.

On April 21, he expansively outlined the many threats that Britain’s advanced air bases on Crete posed to German interests in the Balkans. Not the least of these were bombing raids against the vital Romanian oil fields at Ploesti, the German Army’s main source of oil. Hitler, immersed in the planning of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, reluctantly agreed to the invasion of Crete on the provision that he be delivered a swift and decisive victory.

Fearing Hitler might once again change his mind if preparations stalled, Student and his staff pulled off a logistical miracle by quickly procuring the 1,200 aircraft needed for the attack, code-named Operation Mercury. While brilliantly conceived, Student’s planning for the invasion was in many ways compromised by an unrealistic time frame. The Greek airfields, for example, were ill suited to accommodating so many aircraft and no ships were yet available to carry out additional seaborne landings. The tight schedule allowed little time to accumulate accurate intelligence about the enemy.

Based on air reconnaissance that had detected very few prepared defenses or troop deployments, the Germans believed the Allies were undermanned and totally unprepared. It was a bold assumption. For Student to launch a major operation of this kind without solid, detailed intelligence was deemed an acceptable risk. For the men going into battle, however, it was a matter of life or death.

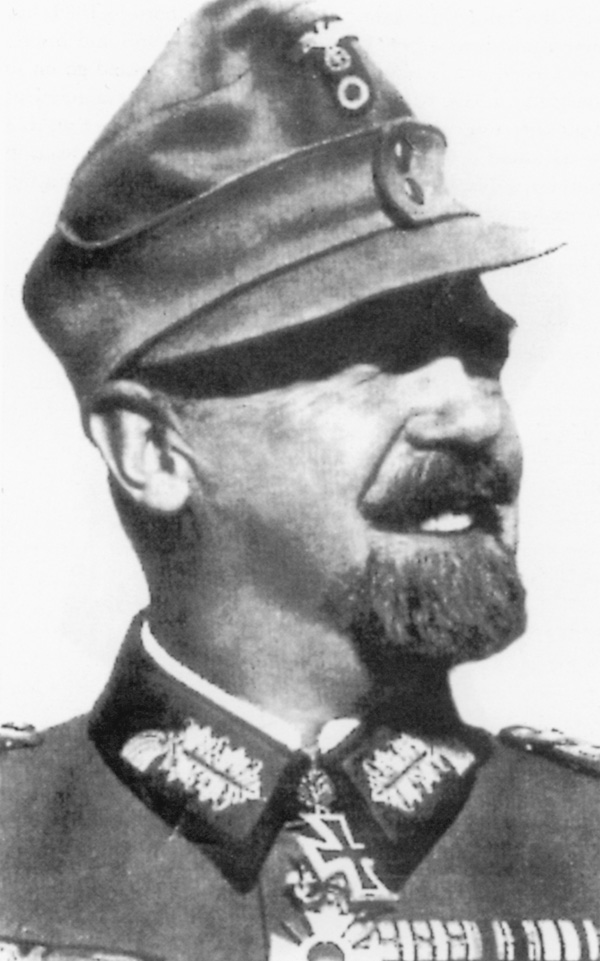

For Operation Mercury, General Student would use his one parachute division, a glider regiment, and Maj. Gen. Julius Ringel’s tough 5th Gebirgsjager (Mountain) Division, part of which would be flown in when a suitable airfield had been captured, the rest ferried across by sea.

The 22,000 troops to be deployed were deemed sufficient to deal with the Allied garrison, estimated to be fewer than 5,000 disorganized, ill-equipped troops likely to surrender at the first opportunity. The reality would be far different.

It was a bold and tactically simple plan that would involve two waves of airborne landings in four locations along the north coast of the island. The first wave of paratroopers and gliderborne troops of the crack Air Assault Regiment, designated Group West, would secure the vital Maleme Airfield and clear the way for sea landings by the mountain troops. Simultaneously, the 3rd Paratrooper Regiment, Group Center, would land and take control of Galatas and the island capital, Canea. The German forces would then link up and push eastward to overwhelm the defenders at Suda Bay, allowing tanks to be shipped across to help roll up the defenders from the west.

During the afternoon, the second wave, Group East, comprising two more paratrooper regiments, would descend on Retimo and Heraklion to seize their airfields and Heraklion’s harbor.

It was a daring undertaking that would see the elite of the German Army launch the first massed airborne invasion in history; Student’s vision of war from the air was about to be realized. When it was over, however, a visibly shaken Hitler would never allow another.

Crete lies in the Eastern Mediterranean between the isles of the Grecian archipelago and the coastline of North Africa and Western Egypt. It is a rugged island approximately 65 kilometers north to south and 265 km east to west. Behind the island’s northern lowland coastal plain rises a narrow mountain range with steep, rugged cliffs overshadowing a labyrinth of defiles, ravines, rock, and scrub that are passable by only a few tracks and rudimentary roads.

The northern half of the island contained the only defensible harbor, Suda Bay, along with Crete’s three operational airfields at Maleme, Retimo, and Heraklion. British Middle East Command had always recognized the strategic importance of Crete, but was stretched too thinly to act on recommendations to upgrade its airfields or reinforce the garrison. It was not until the impending fall of Greece placed Crete as the most forward British position facing the Axis in the Mediterranean that Allied command would take a greater interest in the island.

The question of defending Crete left many senior officers, fresh from the mainland Greece fiasco, harboring grave reservations. They argued that Crete’s physical makeup played directly into the hands of the Axis. All the key airfields, cities, and harbors were located in the north closer to German bases in Greece than British bases in Egypt. In any case, it appeared unlikely that Crete could receive enough equipment and aircraft to defend itself against an invasion.

However, with the swastika now flying triumphantly above the Parthenon, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill dismissed these concerns, gambling heavily on the edge he had secretly attained through the codebreakers at Bletchley Park. As Student forged ahead with his plans at breakneck speed, he was unaware that almost the entire operation had been fatally compromised. For the first time in the war, the Ultra intercepts had given the British almost complete knowledge of what was to come. It was a priceless advantage upon which Churchill was determined to extract maximum value, and in a blunt cable to Middle East Command he made it clear that Crete was to be held at all costs.

The Harbor at Suda Bay was Swamped with a Massive Influx of Exhausted Soldiers, Many of Whom had Arrived with Nothing but Their Rifles.

The upcoming battle would need a fearless commander, and Churchill chose a New Zealander, General Bernard Freyberg, for the job. Not everyone agreed with this decision. Despite his legendary fighting reputation, there were those who felt the 50-year-old Freyberg had neither the training nor intellectual capability for an independent command of such difficulty and complexity. The British Prime Minister, however, would hear none of it, for in Freyberg, Churchill believed he had a fighting general who would inspire the garrison and defend the island to the last.

Toward the end of April, with the Greek campaign in its death throes, the Royal Navy was heroically evacuating as many troops as it could from the mainland. For the sake of expediency many of these men found themselves on Crete instead of in the relative safety of Egypt some 650 kilometers farther south. The harbor at Suda Bay was soon swamped with a massive influx of exhausted soldiers, many of whom had arrived with nothing but their rifles.

General Freyberg, one of the last to be evacuated, was landed at Suda Bay on April 29, expecting only a brief stay before moving on to Egypt. Soon after his arrival the matter of commanding Crete was placed squarely in his lap like a poisoned chalice. He was completely taken aback by the proposal, and the subsequent briefing he received did little to endear him to the task. The island, he was told, could expect air attacks almost immediately, followed up within weeks by major airborne landings supported by a seaborne invasion carrying tanks. His forces, numbering over 41,000 men, were gravely short of equipment, particularly artillery and antiaircraft guns, and could count on little help from the Royal Air Force or Royal Navy. Freyberg, who could not understand why Crete was being defended at all, felt that with most of his New Zealand command already on Crete he had no alternative but to take the assignment.

From his new headquarters outside Canea, the stouthearted Freyberg faced formidable difficulties. In spite of knowing little about Crete, he set to work bringing order to the confusion, processing and organizing the thousands of demoralized troops he now commanded. Recognizing that the close-combat encounter that loomed would be for fighting men only, he saw to it that the wounded and most of the non-essential personnel were evacuated to Egypt. Those that remained amounted to approximately 17,000 British, 7,750 New Zealanders, 6,500 Australians, and 10,200 poorly equipped Greek troops.

The Cretan population, shaped by a tradition of guerrilla warfare, was determined to fight alongside the Allies. Freyberg, not opposed to the idea, wanted them incorporated into a formation similar to the British Home Guard, but nothing was organized before the invasion. Without the protection of military law, many hundreds were to be executed as partisans by the Germans.

Due to the geographical makeup of the island and his prior knowledge of German plans, Freyberg planned his defense around four self-contained fighting groups deployed in the regions where the airborne invaders would most likely seek a foothold. These areas would form the focal points of the Crete defense plan.

The first of these, at Heraklion, would be defended by an 8,000-man garrison comprising Australian, British, and Greek troops under the command of Brigadier B.H. Chappell. The second, in the Retimo-Georgioupolis sector, would have Brigadier G. Vasey commanding Australian and Greek units totaling 7,500 men. The third, in the Suda Bay-Canea sector, was under the command of Maj. Gen. E.C. Weston with a force of 8,000 men, while the fourth, under Brigadier E. Puttick, covered the Maleme-Galatas sector just west of Canea. The New Zealanders in this region were responsible for defending the airfield, the coast, and Prison Valley against the Germans.

Maleme’s airfield was vital to both sides, and its defense fell to Colonel L.W. Andrews’ 22nd New Zealand Battalion which, supported by two dug-in tanks and two artillery pieces, took up positions on the slopes of Hill 107 overlooking the airfield runway. It was a precarious deployment, for the nearest supporting troops would be over two miles away.

Brigadier Puttick’s forces covered the airfield and the coast as Freyberg had ordered, but his defensive lines were very thinly spread, punctuated by yawning gaps that could not be sealed. Effective command coordination under these conditions would be difficult.

Freyberg, who emphasized camouflage and concealment, saw to it that each sector had a sprinkling of field artillery, a few antiaircraft guns, and a couple of tanks. The lack of short-range radios on the island would make communication a problem, leaving Freyberg to rely heavily on the initiative of his local commanders. In public, at least, he adopted a positive outlook, confidant that his men would give an excellent account of themselves. Privately, he had grave concerns.

As predicted, the Luftwaffe was soon launching round-the-clock raids against ships and installations in Suda Bay. To add potency to the attack, Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bomber pilots had been provided with a basic proximity fuse that detonated their bombs just before impact, resulting in a more lethal spread of shrapnel. The harbor was a nightmare of exploding bombs and choking black smoke, but with only a couple of fighters and precious few AA guns, there was little Freyberg could do to help the men on the docks.

Ships that had avoided the Stukas soon found themselves maneuvering through a waterway cluttered with the debris of war to be unloaded by troops who often worked as bombs fell around them.

As the invasion drew closer, the intensity of the air raids increased sharply. The island’s three airdromes at Maleme, Heraklion, and Retimo were given special attention, forcing the Allied command to withdraw Crete’s six remaining fighters to Egypt and leaving the troops with no air cover at all. With raids pushing men at all levels of command to the breaking point, many bitterly observed that “RAF” should stand for “Rare as Fairies.”

At 7:30 am on May 20, an enormous air armada launched fierce strikes around Suda Bay and the vital airfields. The New Zealanders at Maleme were singled out for one of the most concentrated local air attacks of World War II. Their positions were inundated with high explosive and machine-gun fire.

Half an hour later, the main invasion commenced as nearly 600 Junkers Ju-52 troop transports surged slowly toward the island, disgorging paratroopers over the target areas. Brigadier Puttick’s New Zealanders around Maleme bore the brunt of the first attack as troop-carrying gliders and paratroopers of the Air Assault Regiment descended into their midst.

Having lost the element of surprise, the Germans were in trouble almost immediately. Many of the gliders were systematically shredded by intense machine-gun fire while others crashed on the rocky terrain, wounding and killing many of the occupants. Those troops that scrambled to safety quickly rallied to overrun the AA guns south of the airfield, but most found themselves isolated and pinned down by heavy and accurate ground fire.

The men of the Air Assault Regiment fared little better, descending helplessly into a hail of bullets from strong New Zealand defensive positions beneath them. Hundreds of paratroopers, killed before they hit the ground, were paying the ultimate price for inadequate intelligence.

The Paratroopers Found Themselves in a Parched, Dusty Hell Pitted Against Battle-Hardened Veterans Clearly Capable of Holding Their Own.

The airborne forces that had landed near the village of Kastelli encountered an even more hostile reception when they were mercilessly set upon by Cretan villagers as they struggled in their harnesses or while caught in the olive trees. Incidents such as these were repeated at all the drop zones as the population took up arms against the invaders. The Germans had not anticipated this type of determined civilian resistance, but would quickly retaliate with unbridled savagery of their own.

Meanwhile, at Maleme the paratroopers that landed unscathed regrouped in a dried-up riverbed near the western edge of the airfield and provided covering fire for other survivors to link up with them. Instead of quickly subduing a disorganized rabble, they found themselves in a parched, dusty hell pitted against battle-hardened veterans clearly capable of holding their own.

From their foothold near the riverbed, the superbly led paratroopers immediately began assaults on both the airfield itself and the New Zealanders occupying the vital Hill 107 that dominated the sector. In rugged, sun-bleached terrain, battered by searing heat and tortured by thirst, both sides were quickly locked in savage fighting that raged unabated throughout the morning. The Germans were unable to make inroads, so, in a desperate attempt to regain the initiative, they advanced up Hill 107 behind a group of RAF prisoners forced to act as a human shield.

Tragically, many of the airmen were cut down by friendly fire before the defenders realized what was happening. With cries of “shame” ringing in their ears, the Germans were once again forced back.

With most of the senior German officers already casualties, the operation at Maleme was in turmoil. The situation worsened as reinforcements in the Air Regiment’s 3rd Battalion were slaughtered by ground fire within moments of jumping. The few survivors who managed to link up with forces near the airfield were too dazed to offer much fight.

Confronting the dreadful realities of war with all its unimaginable horrors had left many Germans too traumatized to function at all, while scores would surrender at the first opportunity. Crete was not proving to be the glorious adventure these young men had envisioned.

In the face of stubborn resistance, the Germans were unable to push the New Zealanders off Hill 107. By late morning, Freyberg’s forces around Maleme had every reason to be satisfied, for despite mounting German pressure, they had prevented the men of Group West from achieving a decisive breakthrough.

While the troops at Maleme Airfield were paying a heavy price, the men of Group Center in the Canea-Suda Bay sector suffered a similar fate as airborne and gliderborne troops descended into the muzzles of the defenders. Hundreds were killed in the air or captured soon after landing, while many others were dragged to the bottom of a nearby reservoir. The survivors who had landed outside the New Zealand defensive areas quickly converted a prison into a strongpoint to which stragglers from other landing sites soon converged.

The troops who had expected to land on a gently sloping valley found themselves corralled into a funnel-shaped depression surrounded on all sides by the enemy. The only course open to them was to seize the heights around Galatas and from there break through to Canea; the alternative was to be slaughtered where they stood. Once again the New Zealanders were in the thick of the fighting and eager to hit back after weeks of constant air attack.

The Germans pushed toward the village of Galatas, but casualties were high and by late afternoon they disengaged to consolidate for the night in anticipation of a counterattack. Group Center, which failed to take any of its objectives on day one of the invasion, now faced the prospect of being overrun altogether. Here, as in Maleme, the Germans had lost the initiative; any thought of taking the Maleme-Canea sector in the first attack had been completely dismissed.

News of the crushing German losses gave rise to optimism among senior Allied commanders that the situation on Crete was well in hand. Their spirits were lifted further with reports that an attempted German seaborne operation had been thwarted by the Royal Navy. Elements of General Julius Ringel’s 5th Mountain Division, en route to Crete aboard a fleet of commandeered Greek fishing boats, were intercepted by British warships during the night. In a one-sided engagement, the Navy sank many of the small vessels and scattered the rest. Ringel, who had been skeptical about the whole operation on Crete, was seething when he learned two entire battalions had been lost in the ill-fated expedition.

While Freyberg’s defensive sectors had thus far weathered the storm and maintained their lines, the men were low on supplies and feeling the effects of the intense fighting. The warning signs were ominous. Freyberg was frustrated by a totally inadequate communications network that quickly put him out of touch with the developing battles, affording him little opportunity to decisively influence events. The battle was effectively left in the hands of the four sector commanders who, due to a lack of radios, rarely knew what was happening outside their own areas.

In the meantime, an air of crisis pervaded Student’s headquarters in Athens. Reports of the losses at Maleme and Canea had stunned the entire command. The man who had arrogantly anticipated a quick and glorious victory now found himself desperately trying to stave off Germany’s first defeat of the war. Acutely aware of the rumblings of dissatisfaction from Berlin, Student banked heavily that the second series of landings by Group East at Retimo and Heraklion would capture one of the airfields.

horrendous and prompted Hitler to forbid their use in future airborne operations.

The operation at Retimo depended on tight coordination between the air strikes and the parachute drops. Due to hasty planning, however, Student had not allowed an adequate turnaround time for the aircraft from the morning’s landings. As a consequence, the second wave of paratroopers was delayed and did not begin their drop until around 5 pm, nearly an hour after the Luftwaffe raids had ended. The two battalions of the 2nd Parachute Regiment, believing the Retimo Airfield was virtually undefended, were given a hot reception from Australian and Greek battalions under Lt. Col. I. Campbell, who occupied the dominant features on Hills A and B to the east and west of the airfield.

As the transport craft slowly flew in at 400 feet, the Australians opened fire. Within minutes, seven aircraft were shot down. In the chaos that followed, paratroopers spilled out over the ocean and drowned. Some had parachutes that did not open at all, while those who fell among the Australians were killed or captured.

A sizable force had still managed to regroup outside the defensive zone and immediately started to fight its way toward the summit of Hill A. It was a savage engagement in which Australian gunners on the hilltop defended themselves with picks and shovels and fired their artillery into the advancing Germans at point-blank range. Both sides were paying a terrible price, but by nightfall the exhausted Germans had captured the hill at a cost of nearly 400 men. Their attempts to capture the town of Retimo, however, were thrown back by Cretan police and armed civilians who put up violent resistance.

For the landings at Heraklion, Student had gathered his strongest force with the objective of capturing the airfield and harbor. The Germans, expecting fewer than 400 defenders, would in fact be facing close to 8,000 men supported by tanks and deployed in a horseshoe defense around the airfield, town, and harbor.

“The Planes Burst into Flames, [the Men] Leapt out Like Plumbs Spilt from a Burst Bag.”

The air assault commenced late in the afternoon of May 20 with 250 Ju-52s dropping thousands of men into battle. The strong Allied antiaircraft defenses, forewarned of what was coming, quickly went into action and sent 15 transports plummeting to earth. Some artillery on the high ground was able to fire virtually straight through the side doors as the Ju-52s flew past, blowing them to pieces.

One Australian machine gunner recalled, “The planes burst into flames, [the men] leapt out like plumbs spilt from a burst bag. [One aircraft flew] out to sea with six men trailing from the cords of their parachutes which were tangled to the fuselage. The pilot was bucketing the plane about in an effort to dislodge them.”

The intense ground fire forced the air transports to fly higher than normal, which in turn increased the time of the descent; hundreds were killed as they hung helplessly beneath their parachutes. Many who made it to the ground alive were cut down by machine-gun fire or set upon by Cretan civilians. Others were scattered all over the countryside and would take most of the night to regroup.

These tough, resourceful troops gained their bearings and managed to force their way into Heraklion itself. Throughout the night, the ancient town echoed with the sounds of automatic gunfire as running battles raged up and down the narrow streets and lanes.

As at Retimo, the Germans found themselves battling hard against Cretan police and civilians, who eventually forced the paratroops to fall back with heavy losses.

The action at Heraklion descended into a bitter and bloody engagement with the Luftwaffe bombing the town itself and German troops shooting civilians in reprisal for atrocities committed by partisans. The Cretans counterclaimed that their actions were revenge against German troops who had deliberately set alight buildings with people still inside. This vicious cycle of partisan resistance and Nazi reprisal would continue without respite until the end of the war.

The Heraklion landings were a disaster from the beginning. By nightfall the following day, the Allied defenders had collected 1,250 enemy dead on top of the 200 killed during the initial landing. The remaining 500 troops desperately fought on.

Operation Mercury appeared to be coming apart at the seams, but Student would not allow a withdrawal. With his career and the reputation of the airborne forces hanging in the balance, he decided to concentrate all his efforts on Maleme’s airfield, where his troops had at least established a tenuous foothold. He was a desperate man staking everything on one card.

The situation at Maleme, however, was far from encouraging; a serious New Zealand counterattack would have easily overwhelmed the exhausted paratroopers there, spelling the end of Operation Mercury. Student planned to reinforce Maleme with paratroopers and General Ringel’s mountain troops the following morning, but everything hinged on his forces holding until then. Student spent a fitful night with a pistol by his bed, ready to use on himself if the situation collapsed.

With the Germans seemingly in disarray, Freyberg sent a cautiously optimistic cable to headquarters in Cairo: “We have been hard pressed. I believe that so far we hold the aerodromes at Maleme, Heraklion and Retimo and the two harbors. The margin by which we hold them is a bare one and it would be wrong of me to paint an optimistic picture.”

In reality, the battle was about to slip from Freyberg’s grasp as Student’s gamble at Maleme lay the foundations for an unlikely German victory. Preceded by a massive combination of dive-bomber and artillery bombardment, the Germans pressed the attack at Maleme in the early hours of May 21. Boosted by fresh troops and supplies, the paratroopers launched a surprise attack that drove the New Zealand forces off Hill 107.

The Germans then turned the captured guns against Allied positions around the airfield. The New Zealanders, already stretched to the limit of endurance, attempted a belated counterattack at 3:30 am on May 22. With typical ferocity, they launched fierce grenade and bayonet assaults but could not get near the airfield until after daylight. By then it was too late; the Germans were firmly entrenched and could not be dislodged.

Colonel Andrews’ men had put up a stirring defense, but by the third day of fighting nearly half the force around Maleme was either dead or wounded. With communication to his outlying positions lost and little hope of reinforcement, Andrews saw no alternative but to pull his decimated units back from the airfield. It was a fateful decision that altered the balance of force on Crete.

At Maleme, Student now had possession of the vital airfield that the operation so desperately needed, and he wasted no time reinforcing his foothold. Ignoring the intense Allied artillery and mortar fire sweeping the runway, German pilots began flying missions to replace the men and equipment lost in earlier fighting. In retaliation, RAF bombers from Egypt launched aggressive bombing raids on the airfield, but these would have little impact.

As paratroopers began cautiously pushing forward beyond the airfield perimeter to secure Maleme, Student flew in General Ringel’s mountain troops, many of whom had never flown before. Arriving at dusk they found themselves descending into a terrifying inferno of exploding and burning planes. Many were killed as they scrambled from their aircraft. The airstrip at Maleme was not designed to cope with such a large volume of air traffic, and accidents and collisions were commonplace. With burning wreckage piled up on the airstrip, pilots began landing on any open space they could find to deliver the men to the battlefield. The arrival of these additional troops and heavy weapons would allow Student to weather the storm on Crete, but the general found himself losing a political battle in Berlin.

The slaughter of the first day had shocked and angered Hitler. Furious at the prospect of a drawn-out campaign on Crete, he had Student unceremoniously removed from command and replaced by General Julius Ringel. Student was devastated. There was no love lost between the pair, for Ringel thought Student was a dreamer, while Student viewed Ringel as a plodder, blinded by the dust of the infantry.

In spite of Student’s damning assessment, Ringel was a very capable, no-nonsense commander determined to finish the battle on Crete as quickly as possible. Upon assuming control at Maleme, Ringel wasted no time forming three battle groups to get the ground fight firmly in hand. The first would advance west and south to capture Kastelli and clear the way for the landing of tanks. The second was to cover Maleme from the east and push along the coastal road toward Canea, while the third group was to swing south on a wide outflanking move over the hills, forcing the New Zealanders to withdraw their guns, which were shelling the airfield. The ultimate aim was to join up with the survivors of Group Center and drive on to Suda Bay.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the island at Retimo, elements of the 2nd Parachute Regiment were still heavily engaged in a bitter struggle with Australian troops over the hill features that dominated the sector. In a seesawing battle, fighting for control of Retimo Airfield would continue without respite until May 23, when both sides agreed to a three-hour truce to bury the dead and collect the wounded.

With Each Passing Day it Became Clearer to Freyberg That His Forces Were Being Bled White with no way of Making up the Losses.

A joint hospital out of harm’s way was established where German and Australian doctors, working side by side, could share supplies and medicines. With the completion of this humanitarian task, the fight resumed, but the Germans adopted a different strategy. With the capture of Maleme Airfield, the paratroopers concentrated on pinning down the Allied garrison until the situation at Canea and Suda Bay had stabilized.

Ringel’s flanking drive had successfully forced the withdrawal of Allied troops at Maleme, leaving the airfield out of the reach of their artillery. The loss of the airfield severely dented Freyberg’s confidence. Neither an encouraging cable from Churchill nor the fact that the Germans had lost so many men could lift his spirits. All over the island the hard-fighting defenders battled gamely, but their isolated victories were no longer enough to stem the tide now that the Germans had a supply route onto Crete. With each passing day it became clearer to Freyberg that his forces were being bled white with no way of making up the losses. No matter how many German troops they killed, more would quickly arrive to take their place.

Freyberg later remarked, “At this stage … the troops would not be able to last much longer against a continuation of the air attacks which they had during the previous five days … it was only a question of time before our now shaken troops must be driven out of the positions they occupied.”

Having committed practically all his men and running desperately short of ammunition and supplies, he would have no alternative but to order a retreat to a shorter line.

Ringel’s aggressive thrusts around Maleme forced Brigadier Puttick to order a general retreat from the west of Crete to form a new line running from the sea west of the Kladiso River through the Daratsos Ridge to the Australian positions at the base of Prison Valley. With two airborne and one mountain regiment concentrated against his weary men and a second mountain regiment pushing toward Suda Bay from the south, Puttick’s 4th New Zealand Brigade was withdrawn even farther to new positions outside Canea.

After four days of fighting, Ringel’s battle groups, pushing along the coast toward Palanias and through the hills to the south, finally joined with the third group at Stalos. With Groups West and Center finally linked up, Ringel prepared a major drive to overwhelm the Allied troops grimly holding the last defenses before Suda Bay. With Luftwaffe support, he wanted to crash through this line and then drive eastward to relieve the parachute troops at Retimo and Heraklion.

At this time a tragic chapter in the battle of Crete unfolded as German troops probed toward Kastelli. Among the olive groves and vineyards they came across the bloated corpses of paratroopers who had been attacked by Cretans and left lying where they had fallen on May 20. The bodies showed signs of mutilation and torture. The discovery enraged Ringel, who ordered that any civilian caught with a weapon was to be immediately shot and that 10 hostages would be executed for every hostile act against the German Army.

The first to suffer under this harsh policy would be the civilians who had fought alongside Greek troops defending Kastelli. Despite protests from German POWs in the captured town, 200 male hostages were rounded up and shot. Brutal reprisals were carried out in other villages as the Germans exacted savage revenge for the atrocities they claimed had been committed against them.

With the west of the island under German control and assured of a constant flow of reinforcements, morale was again high. On May 25, with 15,000 troops in the Maleme sector alone and the battle now in hand, Berlin Radio belatedly broadcast news of the invasion. It was a clear indication to all that Hitler believed the operation was now going well.

The same day the German public learned of the invasion, a gaunt Student arrived at Maleme to see his men. He was now a mere spectator, only permitted to offer advice and make suggestions; for the dynamic Student it was a depressing experience. With his career in tatters, he had to endure the indignity of watching the operation, which he alone had believed in, being led to victory by a fierce rival. It was a bitter pill to swallow.

As the Germans steadily advanced across Crete, the Allied command in Cairo could see the writing on the wall and ordered Freyberg to pull his forces back to Retimo and make a stand on the eastern part of the island. But it was too late; the road to Retimo had already been cut, the Canea front had collapsed, and Suda Bay was only a day away from being captured. There were really only two alternatives: surrender or evacuation.

Ringel, sensing that the overall Allied effort on Crete was near collapse, urged his men to crush the Allies as quickly as possible and prevent them from falling back toward Heraklion and joining with the forces there. As a result, he neglected the route to the south and concentrated his pursuit along the coast with his mountain troops, leaving the surviving paratroopers in reserve around Canea.

Freyberg had done his best to defend the island, but now it was time to save his men. With the battle all but lost, he saw no other alternative but to order evacuation preparations to proceed. Rumors of a withdrawal quickly caused the roads into the mountains to be crowded with leaderless men and deserters eager to escape the fighting. Freyberg tried unsuccessfully for two days to get orders to withdraw through to the Australians still fighting at Retimo.

By May 29, however, the men there were effectively isolated and too closely pinned down to have any chance of disengaging as a formed body. Utterly exhausted and with barely any food, water, or ammunition and with no hope of relief, the Australians had no alternative but to surrender. It had been a stirring defense that had cost them 120 dead and 200 wounded, but the action at Retimo had cost the Germans over 800 men.

Brigadier Chappell’s forces at Heraklion were confident they could continue to hold the Germans at bay. Despite relentless pressure, Chappell had thrown up such a stiff and spirited defense that the German High Command in Athens had abandoned any hope of a landing in the harbor. However, days of continuous and brutal fighting saw the men, low on ammunition and supplies, nearing the end of their tether.

“Roads Were Wet and Running from Burst Water Pipes, Hungry Dogs were Scavenging Among the Dead.”

With the road south cut by the Germans and reinforcements being dropped out of range, the Allied position had become untenable. The Germans could not get into Heraklion, but Chappell and his men could not get out. Unable to communicate with Freyberg, Chappell was taking orders directly from Cairo, which informed him that the Royal Navy would evacuate his men from the Heraklion harbor on the night of May 28-29, but they would have to leave their seriously wounded behind. As they had done in mainland Greece, the British and Australian troops once again destroyed their equipment and at dusk made their way silently through the stinking wreckage of Heraklion to the harbor.

An Australian officer recalled the destruction they were leaving behind: “Roads were wet and running from burst water pipes, hungry dogs were scavenging among the dead. There was the stench of sulfur, smoldering fires and … broken sewer pipes but over everything hung [the] stench of decomposing bodies.”

The resistance at Heraklion had achieved all its objectives, preventing the Germans from using either the airfield or the harbor. The men had fought magnificently, yet tragically a further 800 would subsequently be killed, wounded, or captured as a result of enemy air attacks en route to Egypt.

While thousands of troops had been successfully evacuated from Heraklion, escape for the troops still engaged in heavy fighting on the main battlefields around Suda Bay, Canea, and Maleme would prove far more difficult. Freyberg wanted to conduct an orderly retreat, but with Allied ships unable to approach Suda Bay these troops faced a 30-mile trek along a narrow road winding across the mountainous backbone of Crete to the southern shore town of Sfakia. With a rear guard comprising Australians, New Zealanders, Royal Marines, and commandos forming a protective screen, the weary men trudged south through vile weather to the beaches from which they might be collected by waiting ships.

Initially, Ringel had disregarded reports that the Allies were heading south; he could not believe that his enemy would contemplate a mass escape from a fishing village. Ringel’s misunderstanding of the situation eased Freyberg’s problems, as did the Luftwaffe’s beginning its delayed move to Poland for Barbarossa. The troops on the road south would therefore be spared the kind of crushing attacks they had experienced earlier, as would the Royal Navy coming to evacuate them. It also meant that air reconnaissance failed to detect the Allied movement southward, affording Freyberg’s men a valuable head start.

The main body initially made solid progress, but likened themselves to “souls marching into Purgatory.” The arduous journey soon began to take its toll as many collapsed, completely exhausted or totally lame. The Germans soon realized what was happening and swung south in a hot pursuit punctuated by several violent clashes with the defiant rear guard.

Braving grave hazards to reach Sfakia, rescue ships would eventually evacuate over 15,000 men from Crete, but for many in the rear guard there was no escape. The sands had run out of the hourglass before they could get to the beach. Sadly, their reward for such a magnificent effort would be years in captivity.

After 12 days of what had been regarded as the fiercest fighting of the war, the Allies had once again been defeated, but it had been a pyrrhic victory for the Germans. Of the 22,000 German soldiers involved, 6,698 were casualties including 3,352 killed. Allied losses were equally grim, with the Army and Navy suffering a combined loss of over 3,500 dead and nearly 2,000 wounded, while 11,835 became prisoners.

Student’s career and reputation had been dealt a terrible blow. He was not decorated for his role in the battle and had no personal contact with either Hitler or Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring for nearly a year. His forces would never undertake another major airborne operation, and for the rest of the war they would fight with distinction alongside the infantry.

Within a short time, Crete’s strategic importance had diminished; the airfields that had cost the lives of so many were rarely used for offensive action. The Nazi policy of terror instigated by Ringel continued unabated during the occupation, with over 3,500 Cretans shot in reprisal for partisan operations.

In 1944, when German forces abandoned Greece, the garrison on Crete was left besieged by local forces until it was, ironically, rescued by the British after the surrender in May 1945.

Richard Rule writes from his home in Heathmont, Victoria, Australia. A veteran of the Australian Army, he works in sales management, enjoys fly fishing, and has written several books.

Students should have issued his troops with stronger parachutes enabling them to jump with weapons and a night time drop or early dawn. Also why didn’t he jump with them.