By Eric Niderost

The Battle of the Nile represents the apogee of the Age of Fighting Sail, a peak that was confirmed at Trafalgar seven years later. Nelson’s destruction of the French fleet in 1798 was the most complete naval victory of the 18th century, a testament to his genius and the accurate firepower of Britain’s Royal Navy.

[text_ad]

Ships of the line were floating batteries, end products of three hundred years of experimentation in naval artillery. Medieval ships were largely vessels of transport, used to ferry soldiers from one point to another. When they did take place, medieval sea battles were land battles on the water, with ships floating extensions of solid ground. Vessels grappled each other, coming close enough for their soldiers to engage in hand-to-hand combat.

Innovations of Shipborne Artillery

The notion of a ship as an artillery platform began to take root in the 16th century.

It is said that the first English ship to carry heavy armament, the six-gun Holy Ghost, was built in 1414, but the idea really came into its own during the reign of King Henry VIII. The Tudor monarch took a lively interest in maritime affairs, and is generally considered to be the “Father of the Royal Navy.” Under his watchful eye ships were built that carried artillery that could pulverize enemy hulls at long range.

Yet the very weight of these metal behemoths was to cause shipbuilders no end of headaches. Larger, heavier cannon had to be placed lower in a vessel, which meant gunports had to be cut into the hull. Such impromptu “holes” in the hull weakened its structure, bringing other dangers as well. Some gunports could be perilously near the waterline, and in high winds or rough seas the risk of sinking was great.

Shipbuilding was an inexact science, with master shipwrights copying successful designs as best they could. It was a process of trial and error, but errors could have fatal consequences.

In 1545 the Mary Rose, pride of England’s fleet, sank when the ship heeled too far to starboard and the sea flooded into its gunports. It seems that the Mary Rose had been refitted in 1536 with heavier guns, and it was these additional armaments that made the ship dangerously top heavy. In similar fashion the Swedish ship Vasa went to the bottom of Stockholm harbor on its maiden voyage because of instability.

By the early 18th century, shipwrights had overcome most of the problems that had plagued earlier builders. Ship design became standardized. Ironically most authorities believe French ship designs were superior to those of Britain’s Royal Navy, but British discipline and innovation offset the Gallic advantage.

Captain Sir Charles Douglas was responsible for a series of tactical innovations that were introduced after 1779, including an intricate block-and-tackle system. This arrangement allowed gun teams to move their cannons as much as 45 degrees from side to side, broadening the arc of fire.

The 32-Pounder

The largest standard gun for a ship of the line was the 32-pounder cannon, which fired a 32-pound solid shot. The 32-pounder was a monster weapon over nine feet long and 5,500 pounds—almost three tons of metal. Its massive bulk was cradled in a wheeled truck carriage and secured to the hull by means of a breeching rope that looped through a ring at the cascabel (the rear of the cannon). The breeching held the gun in place after firing by stopping the recoil, and also checked its movement when the ship rolled.

A typical 32-pounder was served by a 15-man crew and a “powder monkey.” Powder monkeys were young boys—perhaps 10 or 12 years old—whose duty it was to get powder cartridges from the magazine and transport them to the guns. In battle, these fleet-footed lads could be seen racing about the decks, arms loaded with the precious flannel bags of powder.

The Cannon in Combat

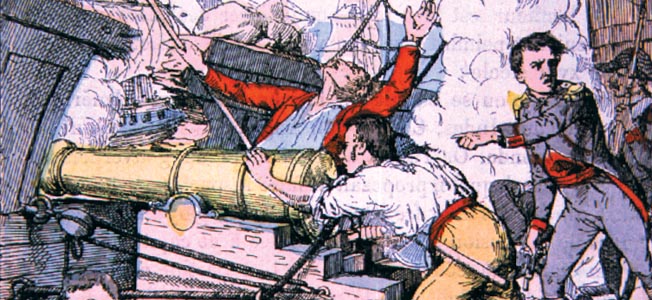

Firing a cannon in battle was a complicated procedure requiring steady nerves and the machinelike motions born of constant drill. Once a gun fired, the recoil rocked it back until restrained by the breeching rope. The cannon muzzle was now some three feet inboard from its gunport—just enough room to enable its crew to reload the squat metal tube. A corkscrew like reamer, or “worm,” was thrust down the muzzle to scrape out any burning remnants of the last charge, followed by a wet sponge to cool the barrel. Both instruments were mounted on poles called staves.

Now the cannon was ready for reloading. A flannel powder charge was rammed down the muzzle into the breech, followed by a wad, a cannonball, and another wad. The whole sequence was jammed into the cannon by a pole called a rammer. The last wad made sure no dangerous gap formed between the powder cartridge and the cannonball due to the ship’s roll. If such a gap did occur, the cannon itself might blow apart when fired.

Each cannon had a gun captain, and it was he who performed the vital last steps. He took an iron pricker and inserted it down the vent or touchhole that was located at the breech. The pricker poked a hole in the powder cartridge that was now securely wedged inside the gun. A perforated goose quill filled with powder was produced—another one of Charles Douglas’s innovations—and then placed in the vent. The goose quill provided a link between the powder cartridge and the firing mechanism, a flintlock and pan. Loose powder from a powder horn was then sprinkled in the pan.

Muscles rippling, the gun crew heaved on the side tackle ropes and ran out the gun until its snout poked out of the gunport. The gun captain cocked the flintlock, and when all was ready pulled a lanyard that brought the flintlock hammer down. The flint made a spark that ignited the pan powder, and a flash was created that traveled down the goose quill to set off the main charge and fire the gun. These maneuvers seem laborious when described, but a well-trained gun crew could fire a cannon in 90 seconds.

It was one thing to go through the motions during drill, quite another to perform them in the heat of battle. Gun crews had to be automatons, because the ear-splitting cacophony of thundering guns, coupled by the smoke and carnage all around them, precluded rational thought. That gun crews could ignore such horrors and keep up a steady rate of fire speaks volumes about the kind of men who sailed during those times.

Hey,

This is an excellent technical and pragmatic description of age of sail warfare. Thanks