by Glenn Barnett

No class of ship in World War II saw more service than the destroyers of the Royal Navy. While capital ships might rest at anchor for months at a time, the destroyer fleet was always busy. From the moment the war started in September 1939, destroyers were at sea performing convoy duty, antisubmarine patrols, rescue operations, minelaying and minesweeping, escort duty for the big ships, shore bombardment, and whatever additional tasks might be required of them. Their work was dirty and dangerous.

[text_ad]

As a testament to their perilous duties, by war’s end 139 of the Royal Navy’s destroyers were lost to enemy action, storms, or accidents. In the early days of Great Britain’s lonely vigil, they were being sunk faster than they could be built. The 50 vintage destroyers given to Britain by the United States in exchange for bases could hardly stem the losses.

The destroyers that participated in the Battle of Cape Matapan were not exempt from harm. Although there were no British naval losses that day, over half of the participating destroyers would soon be lost.

What They Lacked in Size the Destroyers of the British Fleet Made up for in Aggressiveness. They Showed No Fear in Attacking, Even When Outnumbered or Outgunned.

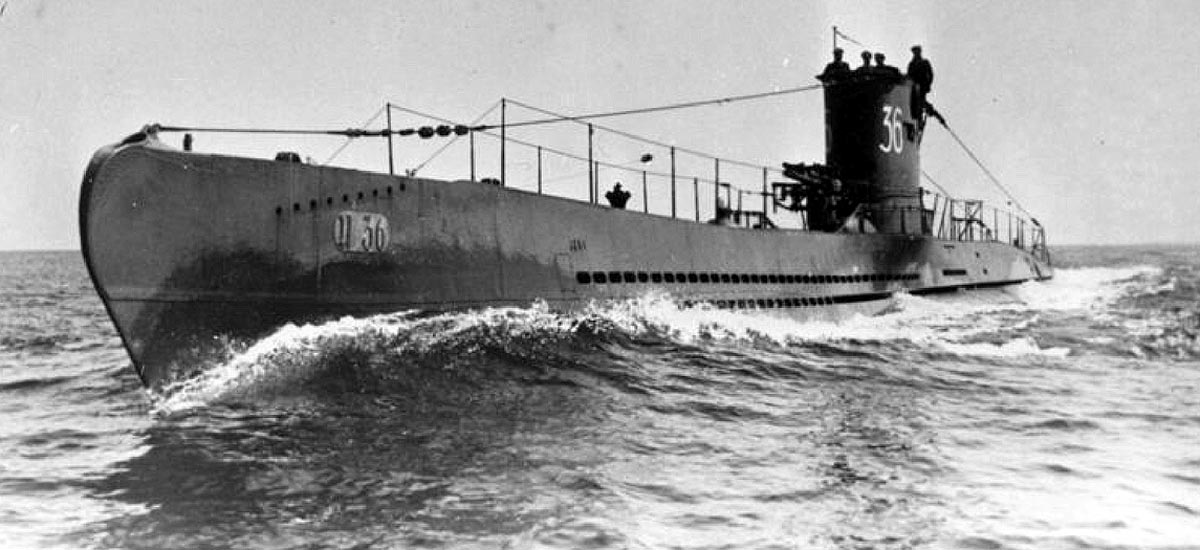

Many of the destroyers at Matapan were already veterans of other fights. Several of them had been at Narvik in Norway. Some had been pressed into service to evacuate British troops at Dunkirk, while others had done escort duty across the Atlantic. Assigned to the Mediterranean, the destroyer fleet was augmented by World War I-era ships of the Royal Australian Navy and convoyed tankers, freighters, and capital ships the length and breadth of the sea. The destroyers attacked Italian shipping and German U-boats and defended against them. It was not easy duty. The crew of one ship, HMAS Vendetta, estimated that they were attacked by bombers 80 times while on assignment in the Mediterranean.

British ship designs of the 1930s called for a destroyer between 1,400 and 1,600 tons. At the same time, German, Italian, Japanese, and American destroyers were larger, faster, and more heavily armed and armored than the diminutive ships of the Royal Navy.

What they lacked in size the destroyers of the British fleet made up for in aggressiveness. They showed no fear in attacking, even when outnumbered or outgunned. At Cape Matapan, Italian Admiral Iachino rightly feared a trap when British cruisers and destroyers fled before him rather than fight it out.

Of the destroyers victorious at Matapan, less than half would survive the war. The German presence in the Mediterranean would grow, and the menace to Allied shipping would increase. During the evacuation of Crete, Hereward and Greyhound were sunk by Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers. In April 1941, Mohawk attacked a German-Italian convoy and was struck by two torpedoes. She sank with the loss of 41 men. In April 1942, Havock ran aground off Tunisia and was scuttled by her crew.

Janus was lost to a German torpedo during the amphibious operation at Anzio after firing over 500 rounds in support of the landings. German radio-controlled bombs struck Jervis at Anzio, causing heavy damage. Jaguar was sunk by torpedoes from U-652. Defender was rendered dead in the water by Italian bombs and sunk by friendly fire rather than abandoned afloat.

Although the fighter planes of the Royal Air Force won the popular imagination and fame for the defense of Britain, the plucky little destroyers bore an equal if unheralded burden.

One of the critical differences between the German and Italian navies and the British navy was the latter’s willingness to lose ships in combat. This in turn allowed for the aggressive tactics which has always been the hallmark of the British Navy. This was all made possible by a large ship building industry that could often replace losses and a culture of Sea Control that enabled many sailors from sunken ships to be rescued. Italy and Germany lacked the ship building capacity to replace losses and this in turn engendered a timidity caused by reluctance to lose ships that could not be replaced.