By Harold E. Raugh, Jr.

Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo was probably born between 4 bc and ad 1. His younger half-sister was first the mistress and then the consort of Gaius Caesar Germanicus, better known as the Emperor Caligula. Not much is known of Corbulo’s early life. One source states that Caligula, hastily traveling to Upper Germany in September, ad 39 to thwart the conspiracy schemes of the army commander there, paused only long enough to replace the consuls of the year with two men he trusted, one of whom was Corbulo. We know little more until Corbulo was appointed legate (legion commander) of Germania Inferior (Lower Germany) in ad 47.

But then men took notice. The Roman historian Publius (or Gaius) Cornelius Tacitus (c.55-117) mentions Corbulo frequently in his Annals. Apparently referring to the general’s command in Germania Inferior, Tacitus records that “Corbulo’s careful methods soon won him the fame…. Bringing up warships by the main channel of the Rhine, and other warships (according to their build) by creeks and canals, he sank the enemy’s boats and ejected Gannascus.” It seems that shortly after assuming command, Corbulo wisely planned an offensive operation that included the use of naval forces and that soundly defeated the Canninefates and the Frisii.

Corbulo Restores Discipline to the Troops

Corbulo’s soldiers, stationed on the fringes of the Empire, had apparently become ill-disciplined and lazy in the performance of their duties. Corbulo found the legions “relaxed in sloth, attentive to plunder, and active for no other end.” He immediately set about restoring the “traditional standards of discipline.” Soldiers were prohibited from falling out of marches, and all tasks and duties, day and night, were required to be performed by the soldiers fully armed. Deviation from, or failure to comply with, the designated standards was not tolerated. Tacitus reports that “two of the men … were put to death as an example to the rest; one because he labored at the trenches without his sword; and the other for being armed with a dagger only.” This strict discipline had the twofold effect of increasing the morale, vigilance, and proficiency of his soldiers and of weakening the morale of the natives.

Corbulo was undoubtedly ambitious, and according to Tacitus, the general secretly set an ambush to trap and kill the leader of a warring tribe. Corbulo’s trap was successful, but gossip at Rome accused him of attempting to stir up “trouble” which would “offend the inactive emperor—and so endanger peace.” The result was that Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus, the Emperor Claudius (who ruled after Caligula), forbade Corbulo to continue any offensive operations, and ordered Roman troops and garrisons withdrawn west of the Rhine River. When Corbulo received the emperor’s orders, he is said to have exclaimed, “Happy the commanders who fought for the old republic!”—recalling the days when Roman generals operated more independently and generally free from any interference. Corbulo, however, loyally obeyed his orders and withdrew his forces.

A Threatened Claudius Recalls Corbulo to Rome

The emperor then inexplicably recalled Corbulo. But to prevent his legionnaires from regressing to an ill-disciplined state while he was in Rome, Corbulo issued orders that kept them busy digging a 23-mile canal connecting the Meuse and Rhine Rivers. Another Roman historian, Dio Cassius Cocceianus, introduces Corbulo in ad 47 as a praetor, a senior magistrate. He further attributes Corbulo’s recall to the jealousy of Claudius, “who on ascertaining [Corbulo’s] valor and his discipline would not allow him to climb to greater heights.”

Even though Claudius recalled Corbulo, depriving the general of victory and martial glory, Corbulo was granted a “triumph,” in itself a great distinction. Corbulo’s popularity was a potential threat to the emperor, and Corbulo was considered “a thorn in the side of the indolent Claudius.”

It appeared that the emperor had eclipsed Corbulo’s career. But an additional factor to consider is Claudius’s imperial policy. Claudius inherited from Caligula an empty treasury, coupled with fear and dissension among many people, but no serious problems on the frontiers. To draw public attention away from Rome and domestic problems, Claudius extended Roman power, primarily in Britain. Claudius adopted a defensive policy along the Rhine, concerned mainly with the development and “Romanization” of this area while minimizing expenditures for the legions stationed there.

In addition, other significant activities arising within the Roman Empire during this period may have had an impact on Claudius’s strategy. Herod Agrippa, a competent client-king, died in ad 44, resulting in the re-annexation of Judea as a Roman province. Two years later Claudius annexed the turbulent Thrace as an Imperial province. After suppressing a violent civil war in Mauretania in North Africa, Claudius reorganized the region into two Imperial provinces. These other distracting and expensive activities may have been factors in Claudius’s reluctance to expand the Empire’s northern frontier.

Nero Restores Corbulo’s Honor

Claudius died in ad 54 from an undetermined cause, possibly poisonous mushrooms. He was succeeded by his 17-year-old adopted son, Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, the son of his second wife, Agrippina the Younger, from her first marriage. Nero inherited from Claudius a precarious situation on the “Eastern Front” of the Empire, which stretched from eastern Anatolia through Syria to the Red Sea. The Imperial policy pertaining to this region, under the Julio-Claudian emperors, was based on a chain of client-states, the buffer of Armenia (a region south of and between the Black and Caspian Seas), and the four legions of the army of Syria.

After years of internal strife, Vologeses, King of Parthia, which was south of Armenia and east of Palestine, invaded Armenia in ad 52/53, deposing the Roman-backed ruler Radamistus and installing his brother Tiridates on the throne. After a short time, however, the Parthians withdrew, enabling Radamistus to return. Radamistus’s vengeful cruelty led to rebellion, and in its wake he fled from Armenia. An Armenian delegation traveled to Rome requesting assistance, and during its absence Tiridates returned and reseized Armenian power. Armenia was in effect no longer a buffer, but was under the direct control of the Parthians.

Nero responded energetically to this challenge on the Empire’s frontier, and decided to restore the border by force. He chose Corbulo to command the expedition. Tacitus notes that “the appointment of Domitius Corbulo to the command of the army in Armenia gave universal satisfaction. The road to preferment, men began to hope, would, from that time, be open to talents and superior merit.” Corbulo’s appointment had removed Claudius’s earlier insult, and had ostensibly shown that Nero was not afraid of military distinction and independence of mind in his subordinates. Thus Nero gained a measure of respect by his appointment of Corbulo.

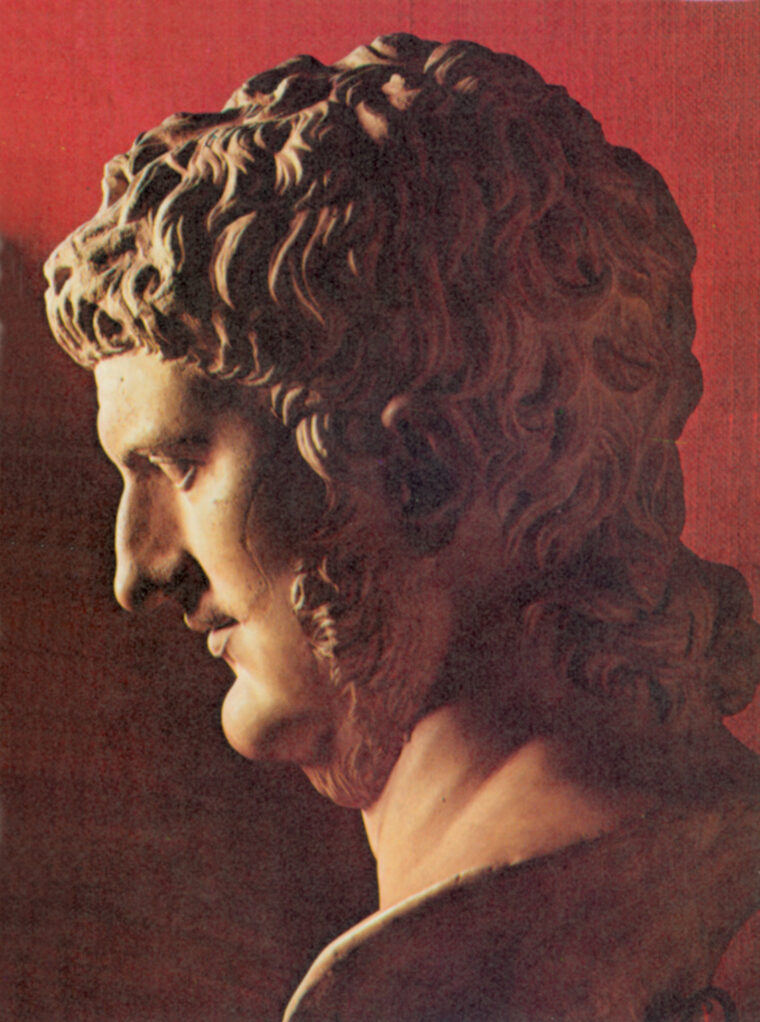

It appears Corbulo was given the special command of the province of Cappadocia-Galatia (now eastern Turkey) and of all legions formed especially for this expedition. The elderly outgoing governor of Syria, General C. Ummidius Durmius Quadratus, resented Corbulo and his authority, causing a ludicrous duplication of effort for some time. Tacitus adds, “The fact was, Corbulo possessed many advantages [over Quadratus]: in his person manly, of a remarkable stature, and in his discourse magnificent,” and that Corbulo “united with experience and consummate wisdom those exterior accomplishments, which, though in themselves of no real value, give an air of elegance even to trifles.”

Corbulo Restores His Legions to Fitness

Corbulo received two legions, III Gallica and VI Ferrata, from Quadratus; X Fretensis and XII Fulminata remained in Syria. Shortly thereafter part, if not all, of X Fretensis was reassigned to Corbulo’s command, and IV Scythica was transferred from Moesia. (A full legion normally had about 5,500 soldiers.) Corbulo found these Syrian legions demoralized and undisciplined, and he had “to struggle with the slothful disposition of his army; a mischief more embarrassing than the wily arts of the enemy.” They had been so “enervated by the languor of peace, that they could scarce support the labors of the army,” reports Tacitus.

Many of these soldiers had never served guard duty, and did not have helmets and breastplates, having served “the term prescribed in garrison-towns … thinking of nothing but the means of enriching themselves.” Corbulo realized he could not hope to win a battle with such a ragtag army, and initiated a relentless program of retraining coupled with harsh discipline. All legionnaires unfit or otherwise undesirable were quickly discharged, and the legions were brought up to full strength by local conscription.

Corbulo patiently trained his legions for over two years. He then took his reinvigorated force and they spent the winter of ad 57/58 encamped under canvas on a bleak plateau in the vicinity of Erzerum, at an altitude of over 6,000 feet above sea level. It was a dreadful winter, and “by the inclemency of the season, many lost the use of their limbs, and it often happened that the sentinel died on his post.”

Were Corbulo’s Methods Too Draconian?

Corbulo resolutely led by personal example during this winter of trials: “He was busy in every quarter, thinly clad, his head uncovered, in the ranks, at the works, commending the brave, relieving the weak, and by his own active vigor exciting the emulation of his men.” Corbulo was physically and mentally robust, but a number of his soldiers were unable to endure the same privations and deserted. This situation required immediate action, and rather than being lenient, Corbulo decreed that deserters would suffer death when caught. Tacitus relates that “the number of desertions, from that [edict, and the enforcement thereof], fell short of what happens in other camps, where too much indulgence is the practice.” It appears such severity was unusual even for this time, and Corbulo’s draconian methods attracted the attention and comment of his contemporaries.

Dio also mentions Corbulo’s strictness and other leadership abilities as reasons for his appointment to command in the East: “[Corbulo] resembled the primitive Romans in that besides coming of a brilliant family and besides possessing much strength of body he was still further gifted with a shrewd intelligence: and he behaved with great bravery, with great fairness, and with great good faith toward all, both friends and enemies. For these reasons Nero dispatched him to the scene of war in his own stead and had entrusted to him a larger force than to anyone else, being equally assured that the man would subdue the barbarians and would not revolt against him [Nero]. And Corbulo proved neither of these assumptions false.”

Tacitus further reports a severe breach of discipline by an officer named Pactius Orphitus, who disobeyed Corbulo’s orders not to engage the enemy before receiving reinforcements and was thus routed. Corbulo passed “the severest censure” on this officer, ordering “him, his subalterns, and his men, to march out of the intrenchments, and there left them in disgrace, till … he gave them the leave to return within the lines.” This appears to be the same incident mentioned by the Roman chronicler Marcus Julius Frontinus, in which Corbulo ordered units that had “given way before the enemy … to camp outside the entrenchments, until by steady and successful raids they should atone for their disgrace.”

Ready for Action

After enduring its final rites of passage in its winter camp at Erzerum, Corbulo knew his small, disciplined, and seasoned force, confident in itself and its leader, was ready for action. In coordination with other allied Roman forces, Corbulo marched against Tiridates, but neither side was able to effectively engage the other. Negotiations ensued. Tiridates then attempted to lure Corbulo to a conference, to which each leader would advance “without their breastplates and their helmets.” Corbulo suspected this to be a trap, a “stroke of eastern perfidy,” and took many of his legionnaires to the designated meeting site. Neither leader, however, was willing to approach the other, and hostilities resumed.

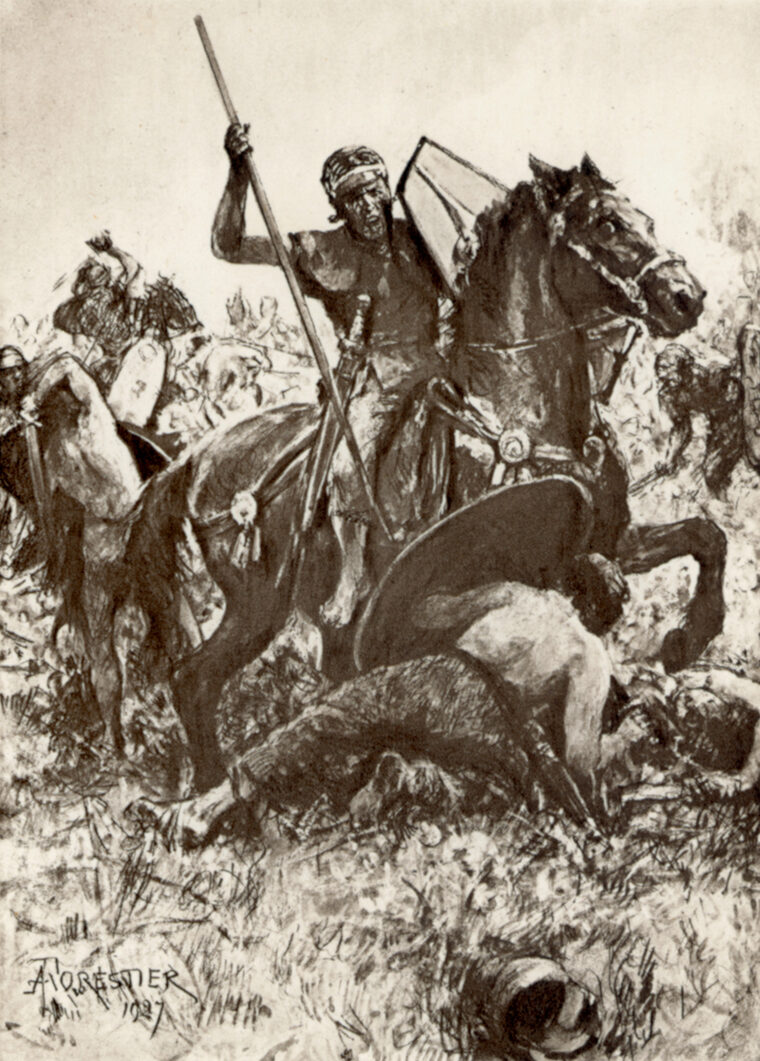

Corbulo wanted the war to end quickly, and in order to “compel the Armenians to act on the defensive,” he “resolved to level their castles to the ground.” Corbulo personally reserved the destruction of the largest fort, Volandum, for himself, and sent his two primary subordinates with their forces to demolish other fortified cities. Corbulo personally reconnoitered the fort. He roused his men with an inspiring speech. He then arrayed his soldiers into echelons, each assigned specific tasks during the assault, and attacked the fort from all sides. They captured the bastion in four hours then “put to the sword” all defenders capable of carrying weapons; the women and children were sold into slavery. Corbulo’s two other lieutenants met with similar successes, and panic and fear spread throughout the Armenian countryside.

Corbulo Sets His Sights on Artaxata

Encouraged by his victories, Corbulo decided to march on and lay siege to Artaxata, the capital of the kingdom. But rather than take the expected direct approach, he took a route by which he hoped to catch the Armenians off-guard.

It didn’t quite work out that way. Tiridates considered ambushing Corbulo while he was on the march, but ultimately lacked the audacity. When Tiridates’ forces revealed themselves, Corbulo was not alarmed because he had “prepared for all events.” Corbulo positioned his forces to repulse an attack from any direction, but the timid Tiridates failed to advance and withdrew his forces at the end of the day.

Immediately Corbulo sent his “light-armed cohorts” to Artaxata. The inhabitants threw open the gates and surrendered to Corbulo’s vanguard. Corbulo destroyed the city in about ad 59, an act that Tacitus rationalizes by stating Corbulo did not have sufficient troops to garrison the fortress, and “if the city were left unhurt, the advantage, as well as the glory of the conquest, would be lost.” For this victory, somewhat ironically, “Nero was saluted Imperator.”

Corbulo then began to march on the major fortress city of Tigranocerta. The Armenians reacted in different ways to the Roman invasion, and Corbulo responded accordingly. “To the submissive, [Corbulo] behaved with mercy … but for such as lay in subterraneous places he felt no compassion,” burning them in their caves.

The long and arduous march continued through the desolate, hot, and rugged countryside, with food and water starting to become scarce. There was “nothing to animate the drooping spirits of the army but the example of their general, who endured more than even the common soldiers.” Along the way, Tigranocerta natives attempted to assassinate Corbulo but failed and were executed.

Then, according to Frontinus, Corbulo worked his wiles. “When … the Armenians seemed likely to make an obstinate defense, Corbulo executed Vadandus, one of the nobles he had captured, shot his head out of a ballista, and sent it flying within the enemy’s fortifications. It happened to fall in the midst of a council the barbarians were holding at that very moment, and the sight of it (as though it were some portent) so filled them with consternation that they hastened to surrender.”

A Short Period of Calm

Nero, knowing the Parthians were still engaged in an insurgency, took advantage of their distraction and ordered Tigranes V anointed king of Armenia. After installing Tigranes, Corbulo left a garrison of a thousand legionnaires in support of the new ruler. Moreover, the kingdom of Armenia was reduced in size, portions being granted for “supervision” to neighboring Roman client-kings in hopes of encouraging Tigranes’ loyalty and good behavior. With the war apparently over, Corbulo withdrew his legions and returned to Syria to assume the governorship, Quadratus having recently died. This occurred about ad 60.

This placid situation was, unfortunately, ephemeral. Soon Tigranes invaded Adiabane (a Parthian dependency), and this provoked Vologeses into attacking and besieging Tigranocerta. Corbulo quickly responded by sending two legions, IV Scythica and XII Fulminata, both under able and trusted subordinates, to assist Tigranes.

Corbulo quite possibly observed that Syria, of great importance because it served as a buffer for Egypt which in turn provided one-third of the Empire’s supply of grain, was highly vulnerable to a Parthian attack. Accordingly, he requested that Rome appoint a commander for Cappadocia, the region north of Syria, while he stayed in command in Syria itself. Corbulo prepared to defend Syria by forming “a chain of posts along the banks of the Euphrates, and, having made a powerful levy of provincial forces, he secured all the passes against the inroads of the enemy.” With realism and forethought, Corbulo also established a series of strongpoints near springs and other sources of water, with the intent of depriving the enemy of this all-important resource.

The Parthians were unable to force Tigranocerta into submission. Corbulo, “not of a temper to be elated with success,” sent an emissary to Vologeses recommending the Parthian king open negotiations with Rome or face the prospect of a two-pronged attack into the Parthian kingdom. While these discussions were taking place, Nero withdrew his support of Tigranes, apparently believing the puppet ruler unsatisfactory and that Armenia needed to be directly annexed.

The Disastrous Appointment of Paetus

Rome sent Lucius Caesannius Paetus, “a catastrophically incompetent man,” to command in Cappadocia. He arrived in ad 62. Tacitus notes the jealousy between Corbulo and Paetus, and the latter “despised the fame acquired by Corbulo.”

Vologeses’ representatives, meanwhile, returned from Rome without a treaty or agreement. The war inevitably resumed. Paetus then had three legions under his command, and failed to take Tigranocerta. He retired to winter quarters, a half-built camp not fully provisioned, near Rhandeia.

As these events were taking place, Tacitus relates, “Corbulo never neglected [his defensive preparations] on the banks of the Euphrates,” and lauds him for his ingenious engineering techniques in successfully building a bridge over the Euphrates—while under fire from the Parthians.

An overconfident Paetus considered the campaigning season over, and permitted many of his soldiers to go on leave. In such a weakened state, Paetus’s encampment was surrounded by the Parthians. Paetus requested help from Corbulo, who led the relief force himself. Corbulo marched his men day and night, but he arrived too late. Paetus had surrendered three days before. He had agreed to an ignominious and humiliating surrender, which included Roman evacuation from Armenia. He also hastily evacuated his camp, disgracefully leaving behind his wounded.

Corbulo the Negotiator

Vologeses was smart enough to realize that Corbulo was no Paetus, and the Parthian king agreed to send envoys to Rome to negotiate a peace agreement.

Shortly thereafter, Paetus was recalled to Rome. Then in the spring of ad 63, Corbulo was granted Imperial, veritably vice-regal, power in the East, “little short of what the Roman people committed to Pompey in the war against the pirates.” Corbulo was also reinforced with a seventh legion, the outstanding XV Apollinaris, which had been transferred from Pannonia (a region near the Danube River).

Vologeses’ envoys were unsuccessful, but after witnessing Corbulo’s immense show of force, Vologeses agreed to meet with him. A compromise was reached by which Vologeses’ brother would receive his crown in Rome from the hands of Nero, thus acknowledging his position as a Roman vassal. An important factor in the success of these talks was Corbulo’s immense personal prestige: “The name of Corbulo was not, as is usual among adverse nations, hated by the enemy. He was, on the contrary, held in high esteem, and, by consequence, his advice had great weight with the Barbarians,” writes Tacitus. Moreover, Corbulo’s moderation, skill, and displays of fairness and good faith, in addition to his “graceful qualities of affability and condescension,” helped ensure the success of these negotiations.

Dio also briefly relates these negotiations, adding that “Corbulo, in spite of the large force that he enjoyed, did not rebel and was never accused of rebellion. He might easily have been made emperor, since men thoroughly detested Nero but all admired him [Corbulo] in every way.” Corbulo was definitely loyal—perhaps too loyal, if that can be said. Tiridates, when in Rome, is reported to have said to Nero, “Master, you have in Corbulo a good slave,” a remark generally interpreted to mean that Tiridates was surprised at Corbulo’s continued loyalty.

Nero’s Suspicions Prove Fatal for Corbulo

Corbulo remained in command in the East. In ad 65 there arose a conspiracy against the Imperial throne that involved many noblemen and senators. Nero’s retribution was swift and merciless. A second plot was known as the “Vinician conspiracy,” apparently led by Annius Vinicianus, Corbulo’s son-in-law, who was also one of his legion commanders. It is probable that the leaders of both conspiracies wanted to replace Nero with Corbulo, but it is unknown whether Corbulo had direct knowledge of these plots.

Nero, however, probably suspected Corbulo. When Nero was on a tour in Greece, he summoned Corbulo, as well as two brothers who were the governors of Upper and Lower Germany, to meet him in Greece for “consultations.” When Corbulo and the other two generals arrived in Greece, in late ad 66 or early 67, Corbulo was greeted with the order to commit suicide. Loyal and honorable to the end, the Roman general uttered one word, the Greek “axios,” a term used in the acclamation of winners in athletic games, meaning “you deserved it.” He then seized a sword and killed himself. Dio interprets Corbulo’s last remark as meaning, “Now for the first time in his [Corbulo’s] career was he ready to believe that he had done ill both in sparing the zither-player [Nero] and in going to him unarmed.” Perhaps.

Thus ended the days of Corbulo, a magnanimous and charismatic warrior, the epitome of a Roman general, and one of the most competent during the time of the early emperors. He held Imperial power in the East for 12 years and had won glory, prestige, and the respect of his troops. In the process, perhaps unwittingly, he had become a formidable threat to and perceived adversary of the Emperor Nero. Corbulo was rewarded for his loyalty, sense of honor, and services by being ordered to fall on his sword and end his own life.

Harold E. Raugh, Jr., is a retired U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel of Infantry. He received his Ph.D. from UCLA and is currently an Adjunct Professor of Military History at the American Military University. He is the author of the forthcoming Victoria Goes to War: An Encyclopedia of British Military History, 1815-1914 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2003).

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments