By Arnold Blumberg

It had been a little over six months since Major General William S. Rosecrans and his Army of the Cumberland had checked the Confederates at the Battle of Stones River (December 31,1862–January 2,1863). Fought 30 miles southeast of Nashville, Stones River (or Murfreesboro as the Confederates called it) secured the Tennessee capital for the North as a base of supply. From there the Federal advance south could continue to the next vital strategic objective in the state—Chattanooga. Its capture would unlock the door to Georgia, thus bringing the South one step closer to ultimate defeat.

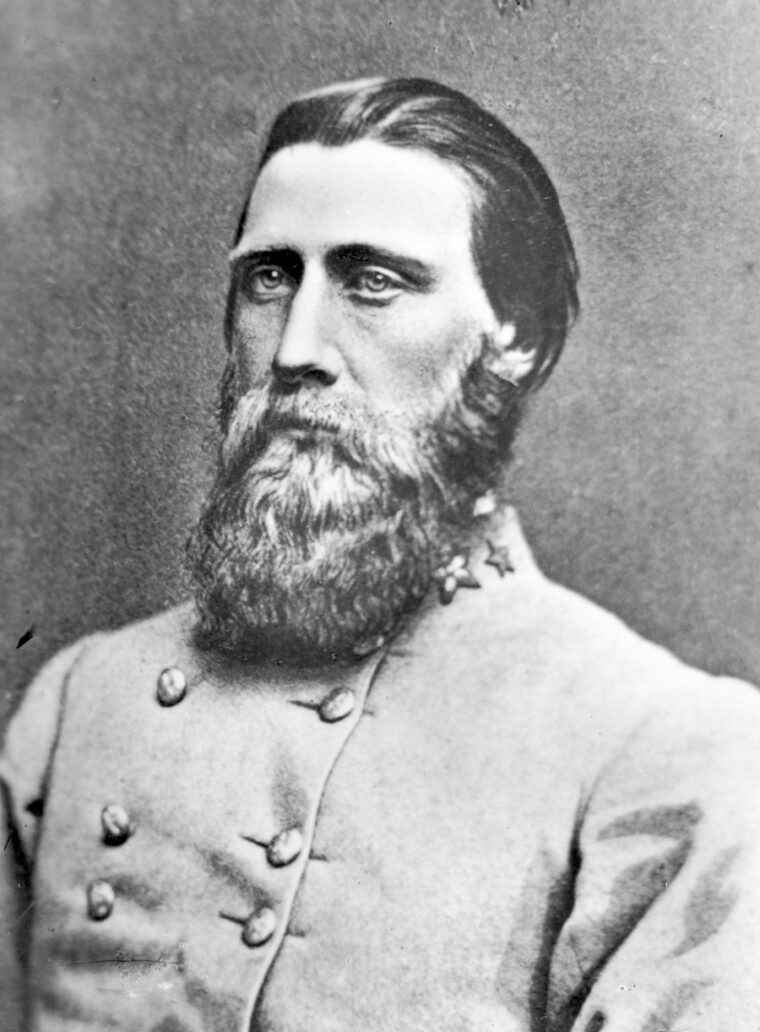

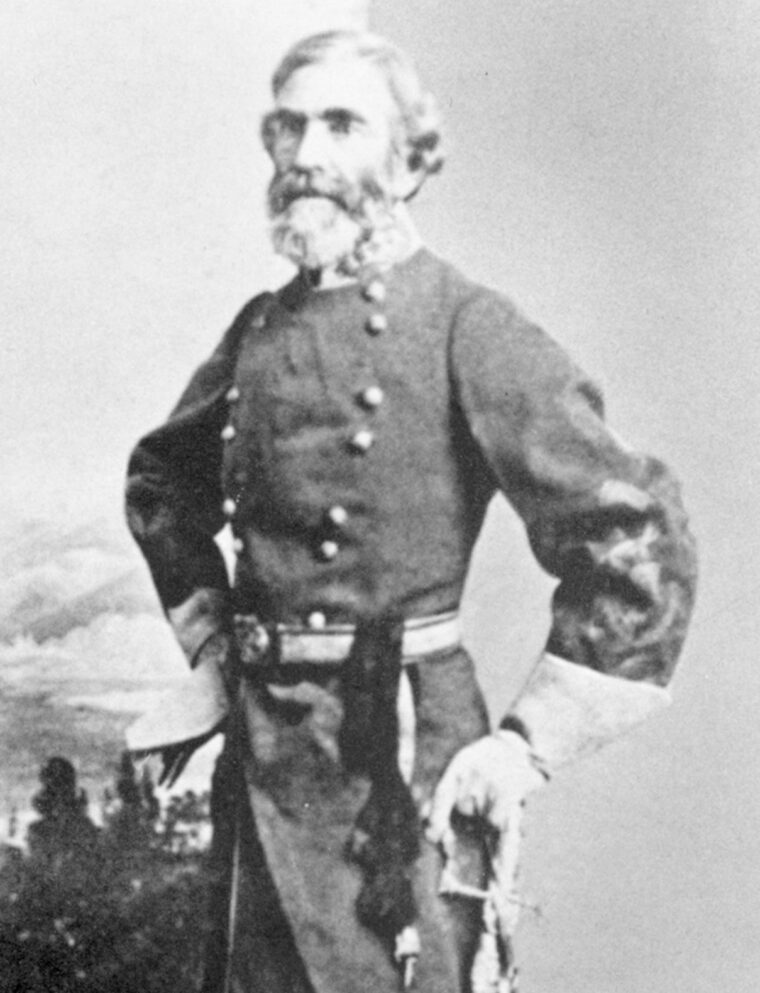

The single most important obstacle to Federal designs on Chattanooga in the summer of 1863 was the principal Rebel army in the West—the Army of Tennessee. Battle hardened and determined, the “second army of the Confederacy” was dogged by ill fortune and a lack of manpower and equipment. As telling as these problems were, they were compounded by the poor leadership of its army commander, Braxton Bragg.

Braxton Bragg: ‘A Dunghill in Disaster’

A graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, class of 1837, Bragg had acquired “a most unenviable reputation” in the western army after two years of war. Dictatorial, quarrelsome, and impatient with most of his officers, he tended to disregard sound advice when proffered, assuming it had been prompted because of ulterior motives on the part of the giver. His passion for strict discipline naturally melded with his obsessive attention to minutiae, preventing him from seeing or understanding the “big picture” regarding a battle, campaign, or the legitimate concern of a subordinate. Thus, he was unable to win the loyalty of his officers and men.

The army’s leaders and soldiers had little confidence in Bragg as a military commander. Many commentators agreed that Bragg’s most blatant shortcoming was his propensity to fall back from the enemy at the critical time when a situation demanded continuation of the battle, or a forward, not backward, step. This may have resulted from his habit of stationing himself too far to the rear and the “strange mental withdrawal that would come over him every time the course of battle would compel him to alter his original plans,”in the words of Lt. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill.

The most concise description of Bragg the military man was written by William Gale, a nephew of Confederate General Leonidas Polk, a member of Bragg’s staff. Gale concluded that “Bragg was obstinate yet without firmness, ruthless without enterprise, crafty yet without stratagem, suspicious, envious, jealous, vain, a batman in success and a dunghill in disaster.”

Combined with inadequate direction from the top, the Army of Tennessee also lacked a hard core of competent general officers to lead it and exert a moderating influence on Bragg. The Army of Tennessee started the war with but a small pool of trained military commanders. Consequently, early in the conflict many brigadier and major general slots were given to nonprofessional soldiers who owed their placement to factors other than their knowledge or experience of war. As the struggle continued this trend remained, mandated by attrition and lack of suitable replacements. Examples were Simon B. Buckner and John C. Breckinridge, political appointees, and Bragg’s senior lieutenant Leonidas Polk, a West Point graduate and Episcopal bishop who frequently treated his superiors “in a manner that smacked of insubordination” and “often chose to obey … only when it pleased him to do so.”

Shortcomings of the Army of Tennessee

In addition to the command problems, the Army of Tennessee was constantly short of manpower and the basic needs of its soldiers to make war. Replacement of lost troops was difficult because the shortfall had to be made good from the more sparsely populated states of the Confederacy such as Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee. Compounding the problem was the logistical base from which the army had to feed, clothe, and equip its members. Constantly narrowed as the war progressed, by the summer of 1863 this base was restricted to eastern Tennessee, Georgia (but only north and west of Atlanta), and northern Alabama. By the time of the Battle of Chickamauga, most of east Tennessee and all of north Alabama had been overrun by the Federals, and the rest of Alabama had been assigned away from Bragg’s army.

The persistent problems of the Army of Tennessee were manifold after the Battle of Stones River. It was apparent to all observers that this force could not, as it stood, hope to either aggressively advance against the enemy and take back Tennessee or adequately defend the vast area placed in its charge. One such “observer,” the Lincoln administration, was keen to take advantage of this military dilemma.

By late 1862 the Federal government had turned its efforts to the conquest of the Confederacy west of the Appalachians. The plan was to sever direct rail and road communications between the Atlantic coast and western portions of the rebel nation. This would then give Federal forces a straight path to the Deep South and its main areas of industry and population. All the while, the drive to literally sever the Confederacy in two by the conquest of the Mississippi River would be ongoing. Control of Tennessee would provide a shield to the Federal efforts to accomplish this. By the middle of 1863 the Union government had accepted military stalemate in the East in return for a powerful Northern concentration against its enemy in the West. The Army of the Cumberland under Major General William Rosecrans would be the instrument responsible for the implementation of this policy west of the Appalachians.

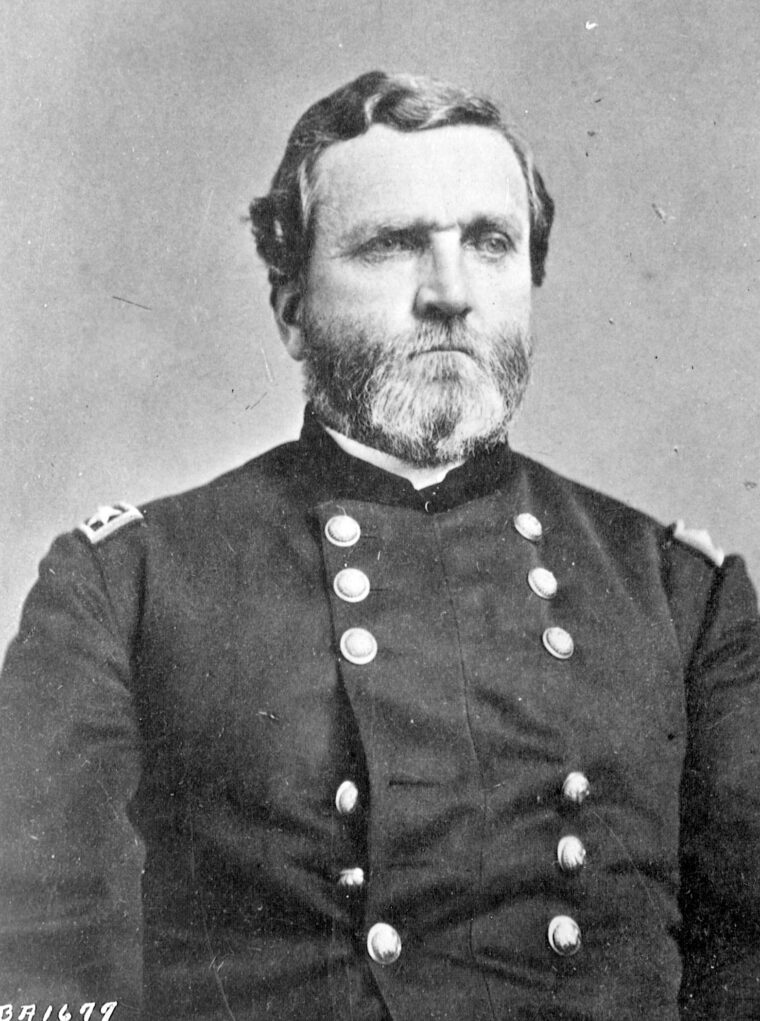

William Rosecrans: Eccentric but Likable

The 44-year-old Union officer was a graduate of West Point, class of 1842. After serving on the staff of George B. McClellan in West Virginia, the Ohioan—a Democrat but active supporter of the Lincoln administration—was transferred to the West as a brigadier general of volunteers. Prominent in the battles of Iuka and Corinth, he was made major general and given command of the Army of the Cumberland. Winning the fight at Stones River (because, unlike his opponent Braxton Bragg, he chose not to retreat from the field), Rosecrans was ordered to follow up his victory by a rapid advance to the vital rail hub at Chattanooga. This he failed to do for another six months despite the threats and pleas forthcoming from Washington. But once the general felt his requirements in men and supplies were adequate for the task, he went on to conduct one of the most spectacular campaigns of the American Civil War.

The Federal authorities back East should not have been surprised that all their cajoling failed to move Rosecrans to action. Like Braxton Bragg, he was one of the most eccentric army commanders produced in the war. But unlike his opposite in gray, he was a far more likeable fellow. His genuine feelings for the welfare of his men were rewarded by the affection they held for him. While Bragg could not elicit loyalty from his officers and soldiers, Rosecrans was showered by it. For his part, the general was loyal to a fault. His sense of obligation to his subordinate commanders prevented him from replacing those who had shown themselves unfit for their positions. Prime examples were Rosecrans’ failure to remove Alexander McCook and Thomas Crittenden, the Army of the Cumberland’s 20th and 21st Infantry Corps leaders, respectively, despite their proven record of military incompetence. When asked why he never rid himself of their dubious services, Rosecrans replied that he could not because he ”hated to injure such two good fellows.”

Unlike Bragg, Rosecrans had a genial disposition; but like his Confederate counterpart, he also possessed a hair-trigger temper. His habit of lashing out at both superiors and inferiors left wounds that did not heal. Compounding his erratic temper was a lack of a sense of humor.

Regardless of its commander’s peculiar traits, the Army of the Cumberland was relatively free from the boiling animosities that prevented the smooth operation of the Army of Tennessee. It had a record of success that bred a sense of intense pride in itself; it was well supplied and kept up to strength as far as possible. With a commander at its helm who was viewed as concerned with the enlisted men’s well-being, this Federal military machine looked forward to any task.

Initiating what would be called the Tullahoma Campaign, Rosecrans moved against Bragg’s Army of Tennessee on June 24,1863. With over 65,000 men, against 44,000 graybacks, the Federal force slipped around the enemy right flank, and for the next 17 rain- soaked days slowly but surely forced the Confederates to retreat. Bragg wanted to make a stand at Tullahoma but was deterred from doing so by Union cavalry that had penetrated into his rear supply areas. The constant contradictory demands of his two top commanders, Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk and Lt. Gen. William Joseph Hardee—the former advocating immediate retreat while the latter lobbied for a grand frontal assault—also did much to impede his judgment as how to counter the Union advance. True to form, and not surprisingly to his army, but to their bitter chagrin, Bragg resolved his dilemma by retreating toward Chattanooga.

In less than two weeks Rosecrans had advanced 100 miles and driven the Confederates out of middle Tennessee for a loss of 570 men as against 2,000 on the Rebel side. Strategically, the campaign was very important. It prevented reinforcements going from Tennessee to either John Pemberton’s or Joe Johnston’s armies at Vicksburg or Jackson, Mississippi, respectively, during the summer of 1863. As a result, the defeat of the Southern forces at those two places and the consequent control of the Mississippi River by the Union were made certain.

The Strategic Importance of Chattanooga

While Bragg and his army took shelter in Chattanooga after their withdrawal from Tullahoma, Rosecrans sat behind the rugged Cumberland Mountains a few dozen miles northwest of the city. Not until mid-August was he finally pressured by Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Army General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck to resume his advance. In the intervening time, Rosecrans’ delay and the threat to Chattanooga his close proximity signaled had caused the government at Richmond to come to a crucial decision: They would reinforce the Army of Tennessee in order to beat back the invaders.

The importance of the city of Chattanooga was apparent by a mere glance at a map. Situated on a bend of the Tennessee River, it was 300 miles south of Cincinnati, Ohio, and 150 miles southeast of Nashville, Tenn., the former being the supply source, and the latter a vast forward supply depot for any Union force operating in Tennessee. A Federal army preparing to enter Georgia would need the city (population about 5,000 in 1863) as a supply base to support its advance south. The four major railways radiating out from Chattanooga connected her to the Midwest via Nashville, the West via Memphis, the Deep South via Atlanta, and Virginia via Knoxville. The city was the gateway to Georgia and the Carolinas, and the Confederates could not afford to lose it without a major fight.

President Jefferson Davis ordered any and all reinforcements that could be found sent to Bragg’s army. The South’s Atlantic seaboard was stripped of its garrisons; forces from Mississippi (John Breckinridge’s and W.H.T. Walker’s divisions) were sent; and, most significantly, 11,000 veterans of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia (eight infantry brigades with artillery) under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet were shipped by rail to boost the numbers of the Army of Tennessee.

As the Confederacy poured whatever manpower it could into southeast Tennessee to save Chattanooga, the Army of the Cumberland finally resumed its march. On August 16, Rosecrans moved forward, separating his three army corps to both flank Bragg’s position and march more quickly through the few passes that penetrated the Lookout Mountain range. A feint up the Tennessee River, followed by the real intended advance down that waterway caught Bragg off guard and turned his position.

Rather than being trapped in the town, the Confederate leader retreated, and Chattanooga was occupied by the bluecoats on September 9. Although outfoxed by his opponent, Bragg, now reinforced, attempted to hit his enemy, who was still widely spread out, in piecemeal fashion. Opportunities to accomplish this arose on September 9, 10, and 12, but the failure of Bragg’s subordinates to follow his orders—owing to their total lack of faith in his leadership—allowed Rosecrans to pull back northward and concentrate his 62,000 men on the west bank of Chickamauga Creek.

Battle of Chickamauga Begins

From the east shore of the creek, Bragg—with a force of 65,000 and expecting additional regiments from Virginia—decided to cross and turn Rosecrans’ northern flank, thus cutting the Federals off from their base at Chattanooga. Having given his adversary four days to concentrate his forces and prepare for a vigorous defense, Bragg nevertheless went ahead with his plan. On September 18, the Rebels fought their way across the creek, but darkness halted their short advance.

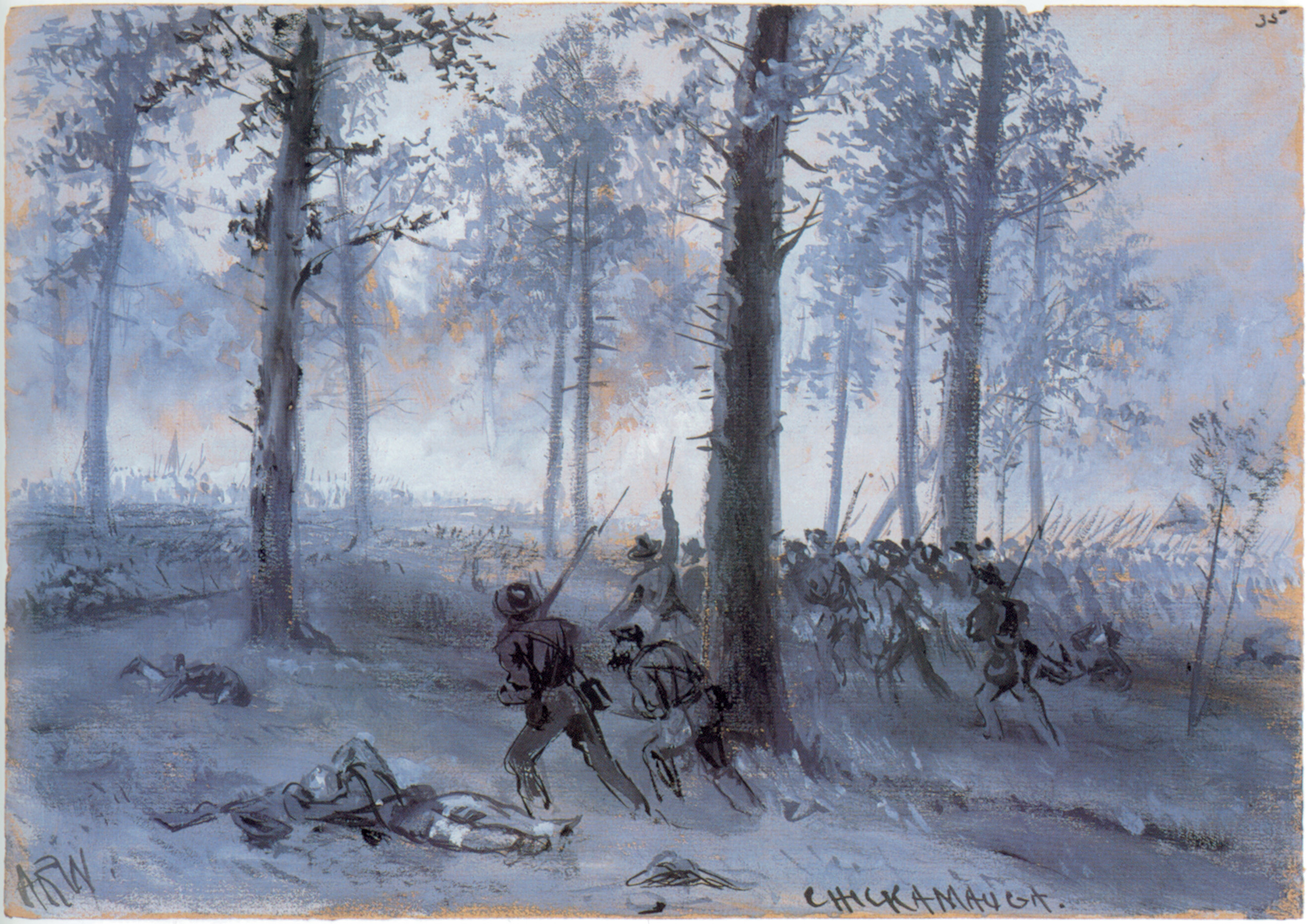

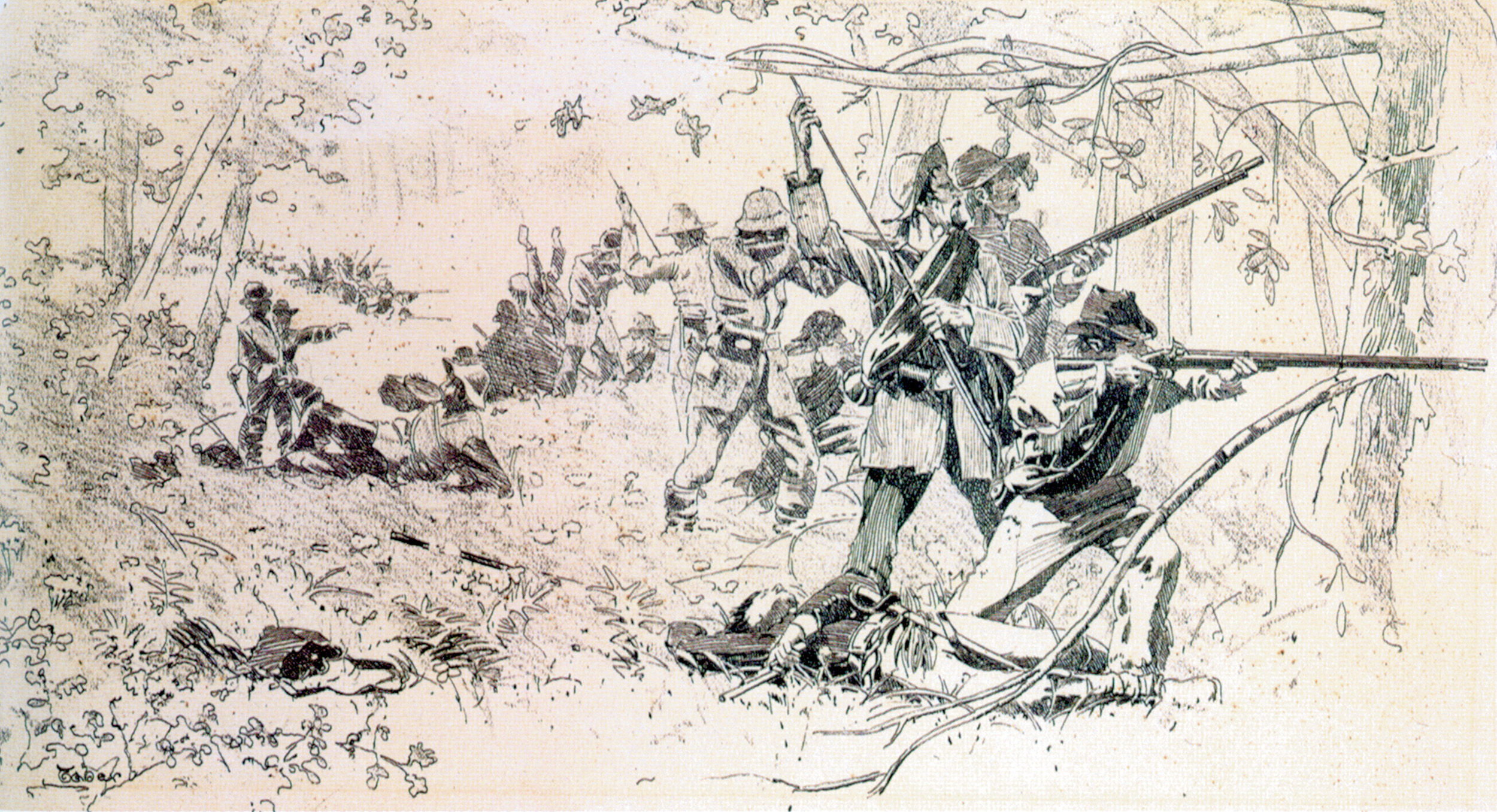

September 19, a Saturday, saw the Battle of Chickamauga commence in earnest. Bragg began the day with a drive southwestward hoping to strike the enemy’s left and drive it toward McLemore’s Cove and away from Chattanooga. But during the previous night Rosecrans had been able to extend his left flank to the north and continued this movement Saturday morning. Bragg encountered Yankees where he did not expect them and his initial plan lost its simplicity. As the day progressed, the battle spread southward. Rosecrans’ main concern was retaining control of the La Fayette Road, his main north-south communication link to Chattanooga. Having been unable to cave in his opponent’s left flank, Bragg spent most of the afternoon and evening fighting off Federal counterattacks, stabilizing his own lines, and figuring out exactly where the enemy army was positioned. A Confederate breakthrough at the Brotherton Field on the left-center of the Union line occurred in the late afternoon but was quickly contained by arriving Federal reinforcements. When darkness enveloped the battlefield the fighting petered out and the two exhausted armies drew a short distance apart.

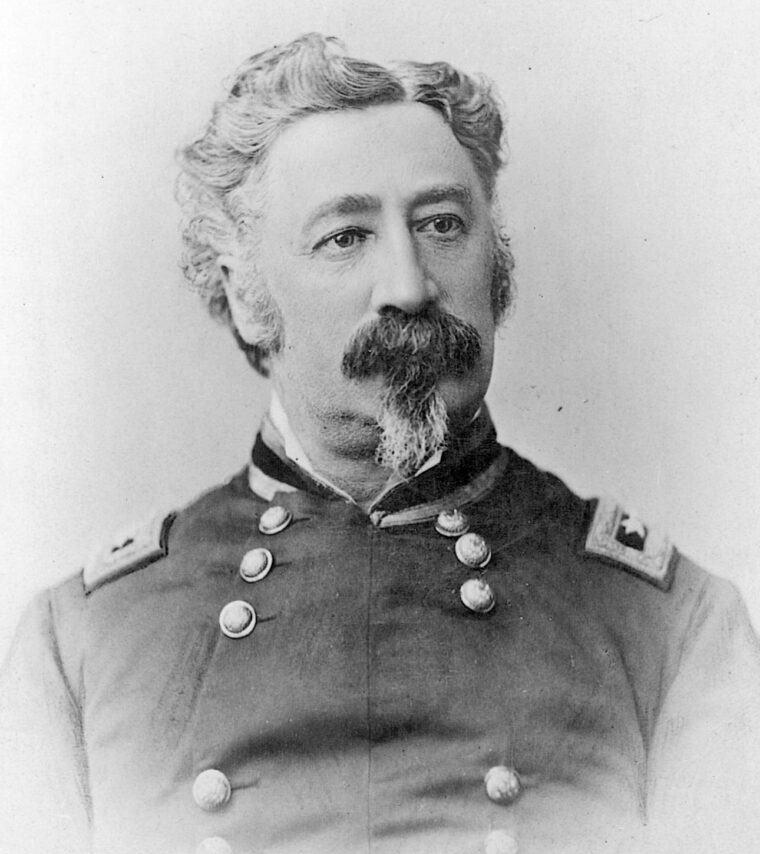

Before the sun rose over the battlefield on Sunday, September 20, both sides had made their plans for the second day’s fighting. Realizing he was outnumbered (about 50,000 Union to around 64,000 Rebels, after the losses of the day before were subtracted), Rosecrans meant to fight a defensive battle that day. He would give special attention to his left, fearing that the enemy would attack there in an attempt to cut him off from Chattanooga. The Union commander was correct: Bragg was determined to continue his effort to turn the Union left (north) flank while applying pressure to the enemy center. To accomplish these goals, the Confederate reorganized his army into a Right Wing under Polk and a Left Wing under the newly arrived Longstreet.

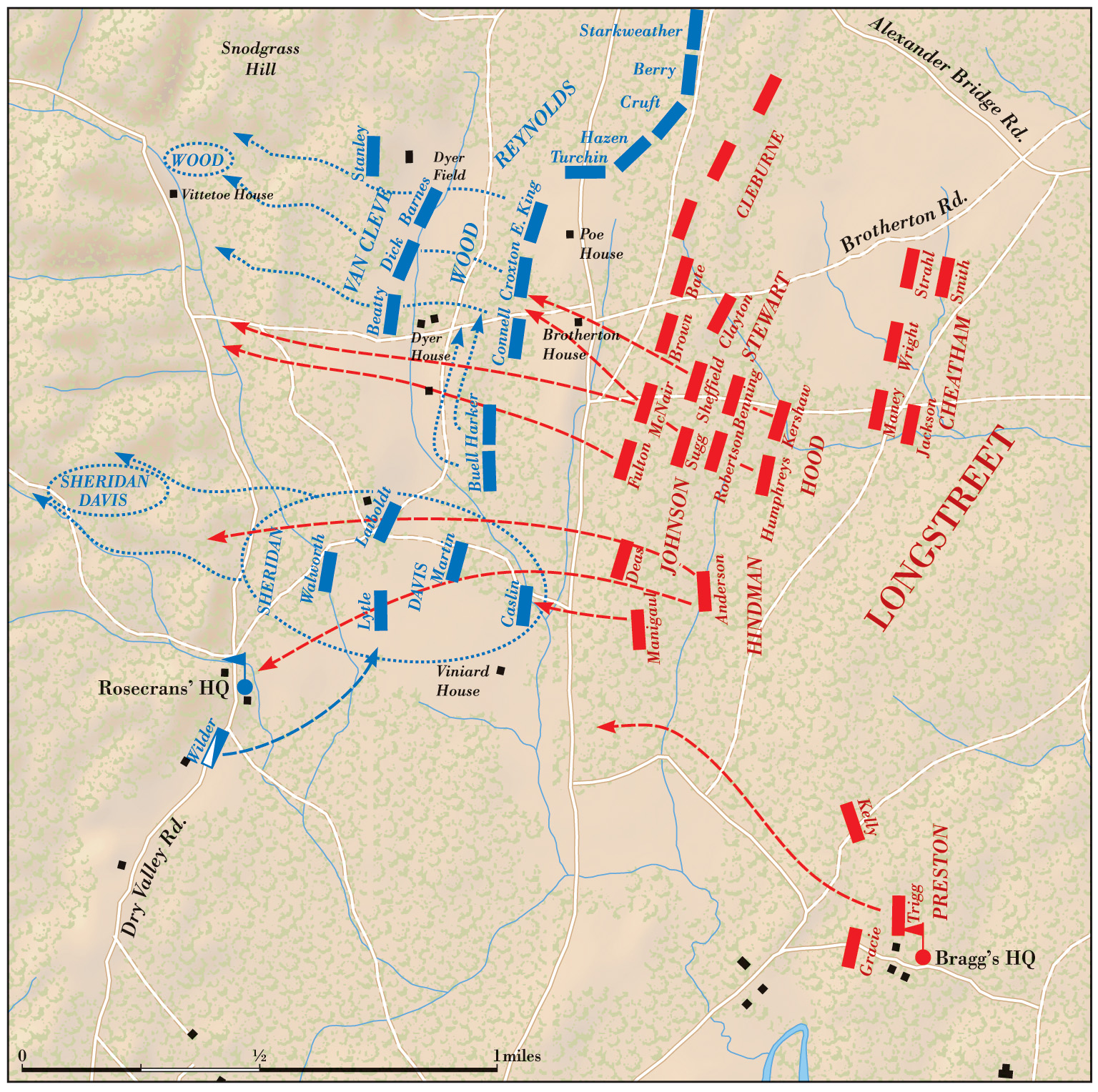

Early on Sunday, Longstreet reached the front to form up his command. Facing the center of the Union line, not more than 300 heavily forested and thicket-strewn yards away, he concentrated eight brigades, formed in a column five brigades deep occupying a frontage of about a quarter of a mile. Commanded by John B. Hood, Longstreet’s battering ram comprised Bushrod Johnson’s division of three brigades—two up front, the third in reserve—followed by Hood’s old division under Evander Law with two brigades forward and one back, and the brigades of Joseph B. Kershaw and George Humphreys directly behind Law. The Rebel phalanx consisted of about 11,000 men. To its immediate left (south) the divisions of Thomas Hindman and William Preston, totaling six brigades, stood ready to parallel Longstreet’s advance and protect his left. It would be 11 am before Longstreet was ready to start his attack.

Fumbling on the Confederate Right

While the Left Wing commander coolly ordered his units into position that morning, the Confederate Right Wing under Polk was fumbling further north. Bragg had sent orders to the prewar clergyman to attack by dawn (about 6 am). Polk did not get his men moving until 10 o’clock. After some promising advances, the planned grand sweep around Union General George H. Thomas’s 14th Corps’ rear stalled and then developed into a much narrower turning movement. This was met by intense Union musket fire. The result was stalemate. With Polk’s Right Wing checked, it would be up to Longstreet’s forces to win the battle for the Confederates.

As the struggle heightened against Polk’s Rebels, more and more Federal units were pulled away from the southern end of the Union line. Rosecrans’ fear for his lines of communication with Chattanooga, bolstered by Thomas’s repeated pleas for aid against Polk, slowly denuded the Federal center and right, already stretched thin. Before 3 am on the morning of the 20th Thomas had asked for reinforcements for his sector in the north. He specifically requested the return of Maj. Gen. James Negley’s division, which was part of Thomas’s Corps. Rosecrans immediately assented and Negley’s three-brigade outfit was ordered out of the Brotherton Field where it had helped plug the gap in the Union center the day before. But Negley was reluctant to leave his position before his relief had come up.

Just before 9:30 am Negley had yet to move even though Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood’s First Division of Crittenden’s 21st Corps was stationed only a few hundred yards west on a ridge bordering Dyer’s Field. Even after requests from Negley, Wood refused to move. Apparently his corps commander, Crittenden, had not fully explained Wood’s responsibility to replace Negley, and the division leader would not budge without definite orders. These were forthcoming when Rosecrans, learning the reason Negley had not yet departed for the north of the Federal line, rode to speak with Woods. At their brief meeting Rosecrans rejected Wood’s excuse that he was ordered by his corps leader to station his command on the ridge west of Dyer Field. With a volley of invectives, the army commander demanded that Wood take up the position Negley’s men then held “… as soon as the Lord will let you.” Without further ado Rosecrans rode away leaving Wood seething with anger. Wood proceeded to move his men the third of a mile to Negley’s site. Ominously, Wood’s skirmishers became engaged with their Southern counterparts as soon as the former entered Brotherton Field.

As Negley moved off and Wood’s three brigades moved east to take his place, Rosecrans continued his efforts to shift his units to firm up his lines prior to the expected general Confederate attack. He moved the 21st Corps’ Third Division under Brig. Gen. Horatio P. Van Cleve first to the ridge Wood had just left, then across the field to the edge of the timber range. Once there he was to deploy two of his brigades (Dick’s and Beatty’s) up front with his third brigade (Barnes’) in support. Not long after, Rosecrans further strengthened his right by putting Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis’s First Division, 20th Corps, on Wood’s right in the direction of the Viniard Farm. Seeing Davis’s position, corps commander McCook, ordered Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan to move one of his brigades, Laiboldt’s, to protect Davis’s right. Lytle’s Brigade of Sheridan’s division was instructed to stay a little back to the west on the Widow Glenn Hill. Sheridan’s third unit, under Colonel Nathan H. Walworth, extended Lytle’s right near the Dry Valley Road. The right of the Federal battle line was completed by Colonel John T. Wilder’s “Lighting Brigade”—five regiments of mounted infantry toting Spencer Repeating Rifles—and part of Maj. Gen. Joseph J. Reynolds’ Fourth Infantry Division, 14th Corps.

With the firing on Thomas’s part of the battlefield growing in volume, Rosecrans now focused on his northern wing. He decided about 10:30 am to draw even more men from his right in order to reinforce his left. To that end he directed Sheridan’s and Van Cleve’s entire divisions to be sent to aid Thomas. To compensate for these withdrawals, the Federal right was to close on its left. McCook would execute Rosecrans’ order and then take charge of the weakened Union flank which would, after the transfer, contain only Wood’s and Davis’s divisions and Wilder’s Brigade.

By 11 o’clock Wilder had received his instructions to move toward Davis. Sheridan got his marching orders about the same time and told his brigadiers, Lytle and Walworth, to form on the Glenn-Kelly Road (a dirt tract below and west of the Brotherton Field, which ran east before it entered the La Fayette Road). Once they formed on the road, they were to move north. Van Cleve was also preparing to depart for the army’s opposite flank.

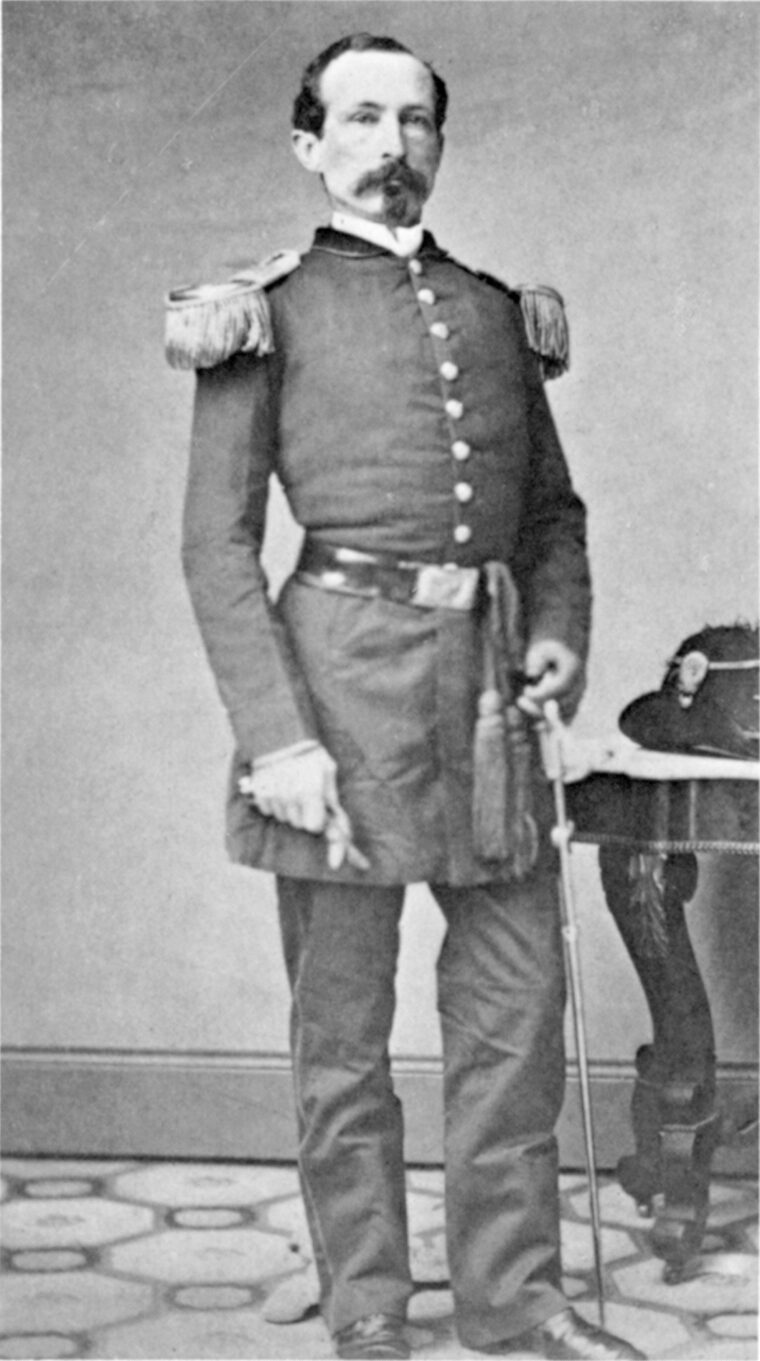

Woods Follows Orders Over Common Sense

A few minutes after 11 am Wood received a messenger from Rosecrans’ chief-of-staff, Brig. Gen. James A. Garfield. The aide carried an order for Wood to “… occupy the vacancy made by the removal of Brannan’s division.” John M. Brannan of Thomas’ 14th Corps had been ordered to Thomas’s left. In fact, there was no unoccupied space between Wood and the next Federal unit to the north—Reynolds’ Infantry Division. (Brannan’s division remained in the interval between Wood and Reynolds, although partially hidden by heavy forest). After reading the missive from Garfield, Wood informed the aide that as far as he knew Brannan was in position and therefore there was no vacant ground between him and Reynolds. He then told the messenger that since the order “was clear and undoubted” Wood would obey it immediately and move his unit from its present position and “close upon him [Reynolds] and support him.” Under the circumstances Garfield’s staff officer was dumbfounded by Wood’s pronouncement.

Thomas John Wood, a 39-year-old Kentuckian, had graduated from West Point in 1845. During the War with Mexico he was breveted for gallantry for his conduct at the Battle of Buena Vista. After the war he served in the regular U.S. cavalry as a captain. In October 1861 he was commissioned a brigadier general of volunteers and led an infantry division with distinction at Shiloh, Perryville, and Stones River. At the latter he was wounded in action but refused to leave the field until the battle was over.

Tom Wood’s injury at Stones River had been painful, but the prickly general had been pained even more by the recent criticism of his army commander. Ninety minutes before being handed Garfield’s order, Rosecrans had upbraided Wood in front of his entire staff for not moving to the front to replace Negley in the battle line. Wood would not undergo that indignation again. His pride blinded his common sense. He ordered his officers to get the men of his division in marching order. In a fit of anger the general was going to leave his present position on the front line unattended and march north and east on the west side (rear) of the Union positions to connect with Reynolds. As the men were formed up, Wood claimed he asked corps commander McCook to fill the position he was about to abandon. Wood claimed McCook agreed to do so, but McCook denied he ever promised any such thing. Nevertheless, McCook did order up Martin’s tiny brigade of Davis’s division, which went in to cover the left of Carlin’s Brigade of the same division.

Longstreet Launches His Grand Attack

In a few minutes Colonels George Buell, Charles G. Harker (Wood’s Division) and Sidney Barnes (part of Van Cleve’s command) were mustered on the Glenn-Kelly Road, ready to proceed north. As the bluecoats formed into march columns, Confederates, in heavy skirmish lines, could be seen approaching not 200 yards distant. Longstreet’s grand attack had begun.

At 11:10 am Longstreet ordered his men forward against the center of the Army of the Cumberland. He had eight brigades packed in a space of just 70 acres of deep forest east of the Brotherton Field. The first line lay 600 yards east of the La Fayette Road and was made up of, from left to right, Gregg’s Tennessee Brigade, Fulton’s Tennesseeans, and McNair’s brigades. They occupied the width of the Brotherton field—about 500 yards. The second line was formed by the remainder of Gregg’s outfit under Colonel Sugg; the third line comprised “Aunt Pollie” Robertson’s Texas, and Sheffield’s Alabama brigades; the fourth Benning’s Georgians; and the last Kershaw’s South Carolinians and Humphrey’s Mississippi regiments.

The first Union soldiers struck by the initial wave of onrushing Confederates were members of Buell’s Brigade who were out in the Brotherton Field acting as skirmishers while waiting to be relieved. They were shattered quickly by Fulton’s and McNair’s troops who swooped toward the La Fayette Road on either side of the Brotherton farmstead. Next, Martin’s Yankees were overrun as they formed behind Buell’s old position marked by a low breastwork built the day before. Any chance Martin’s men would rally vanished as they were flanked on the left by General Zachariah C. Deas’s Alabama Brigade, Hindman’s Division, joining the attack on Bushrod Johnson’s left. Only 20 minutes had elapsed since the Confederate assault had started and Fulton’s men were already at the edge of Dyer Field, entering the enemy’s rear area.

NcNair’s regiments stormed into the woods west of Brotherton Field and smashed into Buell’s Federals while they were still in march column. Most of the Union troops under Buell were stampeded into and across Dyer Field in a complete state of panic. Buell and one of his regiments, the 58th Indiana Infantry, were able to retire west of Dyer Field. Among the confusion the 13th Michigan (Buell’s Brigade) was able to place so much fire, followed by a bayonet charge, on McNair and his men that they were driven back to Brotherton Field. But the Wolverines were in turn charged by Sugg’s four Tennessee regiments and sent “pell-mell” back beyond the La Fayette Road. In the meantime, as Johnson drove due west toward Dyer Field, Hood brought his division forward and veered to the north to eliminate some Federal resistance from that direction. Led by Sheffield’s men, followed by Benning and Hood’s old Texas Brigade, the Confederates smashed into Colonel John M. Connell’s Brigade of Brannan’s Division, 14th Corps, overthrowing the Northerners and capturing three pieces of artillery from Battery B, 1st Michigan Light Artillery. The wreck of Connell’s Brigade and the artillery fled across Dyer Field.

Next to fall to the Rebel tidal wave was Sam Beatty’s Brigade from Van Cleve’s Division. It had been behind Connell’s brigade waiting to enter the Glenn-Kelly Road on its way to help Thomas. The resulting pandemonium saw Beatty’s four regiments dissolve in flight through Dyer Field. There in the mist of his broken units rode General Van Cleve, trying to rally his boys until he was carried from the field by the rush of his retreating troops.

Brigadier General John M. Brannan, commander of the Third Division of the 14th Corps, was nearby and tried to keep what was left of his division in the fight. To that end he ordered Colonel John T. Croxton to face his brigade to the south and block any Rebel advance coming from that direction. He was supported by Battery C, First Ohio Light Artillery. No Confederates came at Croxton’s position until shortly before noon. “Old Rock” Benning and his Georgians squared off against Croxton along the southern edge of Poe Field. They charged the Federals from 200 yards out and were staggered by enemy rifle fire. A firefight ensued, Croxton was seriously wounded, and the Yankee brigade and its companion battery retreated, half to Dyer Field, the rest in an orderly fashion to join Reynolds’ troops farther north.

It was now about 11:45. Bushrod Johnson’s command (the brigades of Fulton, Sugg, McNair, Sheffield, and Robertson) had advanced into Dyer Field. But much more had to be done according to Hood when he came upon Johnson. He ordered Johnson to continue the advance and take the ridgeline just ahead.

Laioboldt’s and Deas’ Disastrous Charges

A little south of Johnson’s victorious concentration, beginning at 11:20 am, the Alabama Brigades of Zachariah C. Deas and General Arthur M. Manigault, followed by Patton Anderson’s Mississippi Brigade, moved to the attack. Their first Yankee victim was Brig. Gen. William P. Carlin’s outfit, which was rapidly flanked and broke to the rear upon first contact. All this was viewed with apprehension by Colonel Bernard Laiboldt’s men stationed on a hill (thereafter known as Lytle Hill) 500 yards to the west. The brigade’s four regiments were stacked one behind another, a good defensive arrangement for it and its supporting artillery battery, but a poor one for an attack. And attack was what the newly arrived General Davis wanted Laiboldt to undertake. The colonel declined the general’s demand.

While Laiboldt and Davis argued the matter, corps commander McCook rode up. He ordered Laiboldt to charge the enemy immediately. So impatient was McCook for the move that he would not allow the brigade to form from a column of regiments into a line of battle. The result was as tragic as it was predictable. Laiboldt’s men marched down the hill into the volleys of Deas’s Confederates, which struck each Union regiment in succession from the left, right, and center, causing the whole to fold and retreat. Deas pursued the broken and fleeing bluecoats back up the wooded hill. But halfway up the Alabamians were met by the withering fire of the 88th Illinois Infantry Regiment (Lytle’s Brigade) sent by Sheridan to help the faltering Laiboldt. Following behind the 88th was Lytle and the rest of his command, which had been at the base of Lytle Hill on the Glenn-Kelly Road, ready to depart for the northern end of the battlefield.

Deas was stymied just short of the hill crest and took fearful losses until fortune once more sided with the Confederates. On Deas’s left, Manigault kept moving west, producing a gap of several hundred yards between him and Deas, a gap that one of Sheridan’s brigades—under Colonel Nathan Walworth—was about to enter. Seeing the danger, Hindman ordered up Anderson’s Brigade from the second line to plug the hole. Anderson’s move motivated Deas to renew his assault on the high ground. With the Confederates converging on his position from three sides, Lytle was killed and his brigade broken. Off to Lytle’s right Walworth, after fighting Anderson’s regiments to the left and Manigault’s on the right to a standstill for 20 minutes, was finally flanked on both sides and forced to retreat. By noon Sheridan’s division was a shambles and Deas and Anderson were 300 yards east of the Dry Valley Road deep in the Union army’s rear.

All the general officers on the Federal right, including Rosecrans, knew that the battle had been lost in that quarter after Sheridan’s defeat. They were content to let their beaten men leave the field and seek safety beyond Missionary Ridge, or with Thomas to the north. However, Colonel John Wilder’s Brigade, along with Lilly’s Indiana Battery, appeared on the field a little after noon. They had come from the army’s extreme right to close the distance between it and Sheridan’s force before Hindman’s attack. Instead of friendly Sheridan they found Confederate Manigault and went after him with a vengeance. Manigault’s Brigade was just then engaged to its front by remnants (less than a regiment and a half) of Sheridan’s infantry and a few artillery pieces. Emerging from the Glenn-Viniard Road, Wilder’s men poured volleys of Spencer rifle fire into their surprised opponents. Hit in the flank, Manigault tried to withdraw but his command fell into rout with Wilder in hot pursuit, driving the graybacks east to the La Fayette Road.

The appearance of Rebel Colonel Robert C. Trigg’s Brigade (from Brigadier William Preston’s Division) caused Wilder to retire back to Glenn Hill. By 1 o’clock the Union colonel was forming his regiments in preparation for a flank attack on Hindman and Johnson’s Confederates. But Sheridan had sent word that the closest friendly troops to Wilder, on what had been the Union right that morning, were over three-fourths of a mile to his rear and advised the colonel to “get out of there.” Undeterred, Wilder was still going ahead with his planned attack when Special Assistant to the Secretary of War Charles A. Dana appeared. Running for the safety of Chattanooga, Dana had wandered into Wilder’s area and ordered Wilder not to carry out his scheme or try to cut his way through to Thomas. He demanded that Wilder withdraw to Chattanooga. Wilder, not knowing Dana’s exact authority, assented, but did not leave the battlefield until after 3 o’clock. He spent about two hours gathering up Union supply wagons and artillery units that had been scattered during the fighting on the right. He then formed an escort for McCook’s reformed supply trains and herded them up the Dry Valley Road toward McFarland’s Gap and Chattanooga.

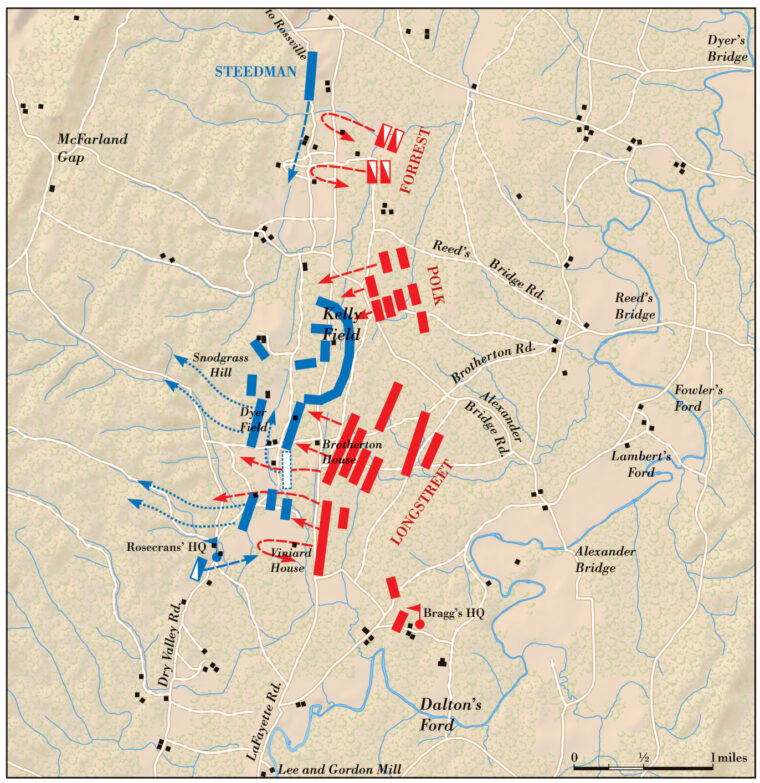

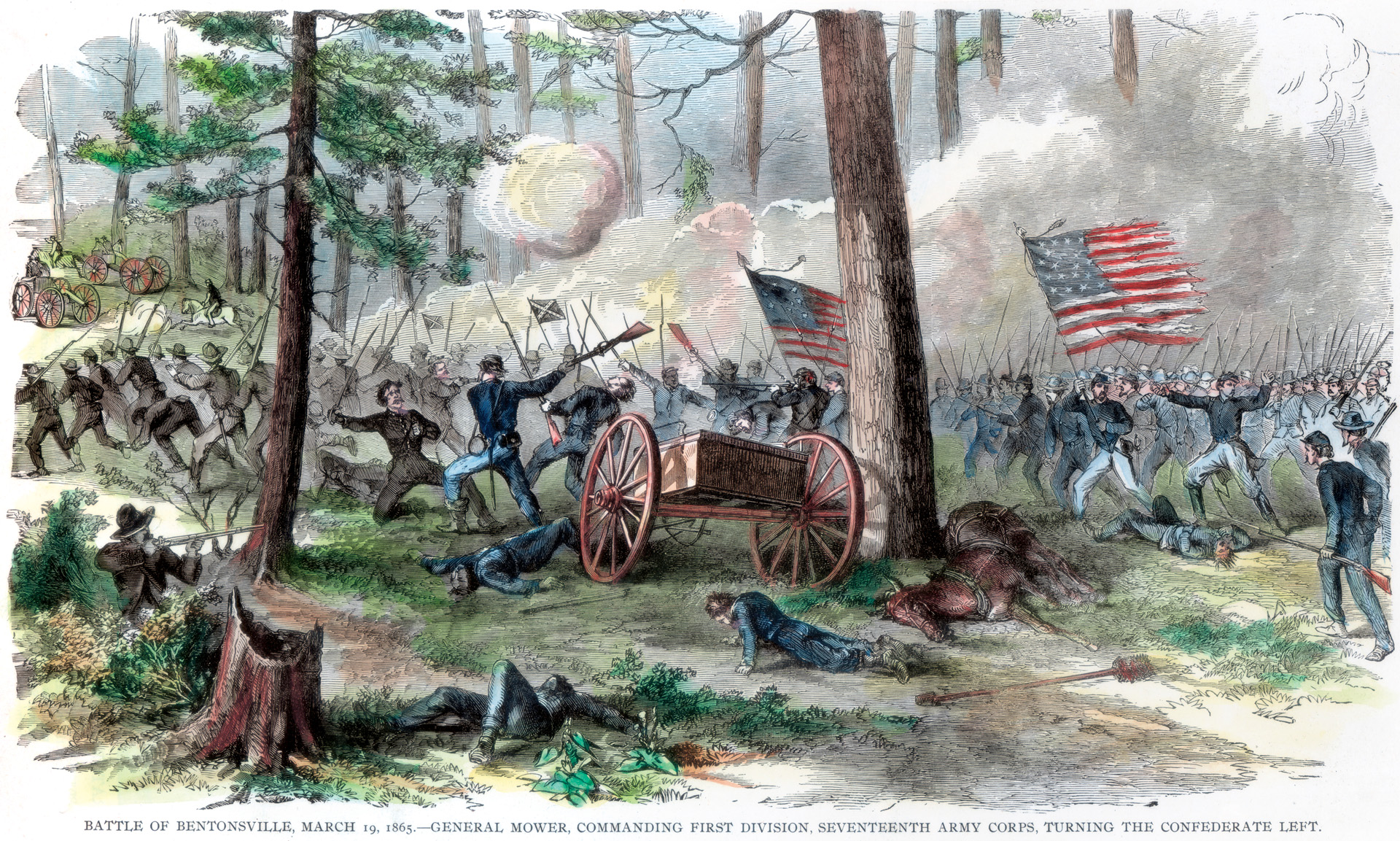

With Wilder’s departure, the fight for the Federal center and right ended, but the Battle of Chickamauga didn’t. It would continue for the rest of the day as the Confederates turned their attack to the north and the killing grounds of Kelly Field, Horseshoe Ridge, and Snodgrass Field. Thomas held on to his position all through the terrible afternoon of the 20th in one of the most remarkable stands made during the war. He then retreated after dark.

Longstreet’s Assault Made the Difference

Chickamauga was one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. More casualties may have been suffered on the first day than at Antietam, but army records did not distinguish between losses of the first and second days of the battle. The Confederates lost about 18,000 men, the Federals about 16,600.

Longstreet’s assault on the Federals at the Battle of Chickamauga rivaled any such effort attempted during the American Civil War. Such decisive assaults were rare during that conflict, and only at First and Second Manassas and the Battle of Nashville did an attack occur that not only smashed the enemy to pieces, but assured a clear-cut victory. Even in the latter two struggles, a large flank maneuver was the prime ingredient in their success.

The tactical achievement of Longstreet’s action led to a Confederate triumph that stalemated the Federal advance in the West for two months, broke the North’s string of victories, and shook the Union’s confidence as to the war’s outcome. It was well thought out, executed to perfection, and graced with good luck. It was one of the grandest actions of the war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments